INTRODUCTION

Against a background of increasing misuse of pharmaceuticals in Australia (Australian Government, 2012; Nicholas, Lee, & Roche, 2011) and overseas (International Narcotics Control Board, 2016), particular concerns have been raised over misuse by young people (Lasopa, Striley, & Cottler, 2015). In the US, attention has often focussed on the rise in illicit use of pharmaceutical opioids and other analgesics (Maxwell, 2011), but emergency responses linked to the misuse of substances, such as benzodiazepines, anti-convulsants, and antidepressants, have also risen significantly (Bachhuber, Maughan, Mitra, Feingold, & Starrels, 2016; Lloyd & McElwee, 2011). Although there are well-documented health issues associated with the misuse of each of these substances, further risks may be incurred when these substances interact with other drugs in an uncontrolled manner, such as increased likelihood of overdose and other adverse reactions. Additionally, mental health issues are more likely to be reported by poly-substance users (Salom, Betts, Williams, Najman, & Alati, 2016). This places young adults, among whom poly-substance use is common (Connor, Gullo, White, & Kelly, 2014), at a high risk. As such, groups who regularly use multiple substances are of public health concern (Bachhuber et al., 2016), despite many regarding their substance use as non-problematic.

Concern has been expressed about these risks in Australia (Lloyd & McElwee, 2011; Nielsen & Bruno, 2011), but few reports have been published on the levels of use among non-clinical populations (Dunlop, 2011), and most focus on a single class of substance or on prescription medications only (Nielsen & Bruno, 2014). One recent study from New Zeland described a significant illicit use of a range of pharmaceuticals in a sample of regular drug users (Wilkins, Sweetsur, & Griffiths, 2011). Other research in New South Wales highlighted a diversion of pharmaceutical stimulants (Kaye, Darke, & Torok, 2014), however little is known about the risks associated with this type of use.

Here we report on mental health issues in a recent national sample of individuals who are regular psychostimulant users and typically report using multiple substances (Sindicich & Burns, 2015). Our aim was to examine extra-medical or illicit use of pharmaceutical substances among a group of regular psychostimulant users (RPU) and to examine links between mental health problems and illicit pharmaceutical use.

METHOD

Study design

The Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS) study is a cross-sectional study conducted annually in each capital city of Australia since 2000, interviewing a sentinel population across a range of jurisdictions to understand rapidly emerging trends in patterns of use and associated health issues. A detailed description of the EDRS and its methodology may be found at http://www.drugtrends.org.au/reports/national-report-2015-ecstasy-and-related-drugs-reporting-system-edrs/. The present study is a secondary analysis using data from the 2015 EDRS (Sindicich, Stafford, & Breen, 2016).

Participants

We used a purposive sampling method which included posters in entertainment precincts, street press, targeted radio and internet advertisements, and word of mouth during April 2015. Potential participants contacted a central coordinator by telephone or email, who then established their eligibility and booked an interview time and location. People who reported regular use (at least monthly during the past six months) of illicit psychostimulants (i.e., ecstasy, cocaine, methamphetamine, LSD, or analogues of these), were eligible for the study. Those who were under sixteen years of age, who had not resided in the location for at the past 12 months, and those who regularly injected illicit substances were excluded. The 2015 sample used in this study comprised 763 regular psychostimulant users.

Sites

Participants were recruited and interviewed in the capital cities of each state/territory in Australia: Canberra, Sydney, Brisbane, Darwin, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth, and Hobart.

Measures

Participants reported on the amount and frequency with which they used illicit drugs over the past six months, as well as illicit or extra-medical use (i.e., consumption of a substance not directly prescribed to the user, or for purposes other than the intended medical use) of pharmaceutical stimulants, over-the-counter (OTC) codeine, other opioids, benzodiazepines, antidepressants and antipsychotic medications.

Participants also reported whether they had experienced “any mental health problems” in the last six months, with the subsequent option to specify a problem (e. g., depression, anxiety, drug-related psychosis), and were assessed for symptoms of psychological distress using the Kessler-10 (K10) scale (Kessler & Mroczek, 1994). This standardised 10-item scale has been found to have good psychometric properties and to identify clinical levels of psychological distress (as measured using the DSM) in the general population (Andrews & Slade, 2001; Kessler et al., 2002), but has also been validated with drug using populations (Hides et al., 2007).

Both total scores and a binary variable indicating high levels of psychological distress (K10 score over 21) were used (Hides et al., 2007). Participants also reported help seeking behaviour (having visited a mental health professional) and receipt of medication for mental health problems during the last six months, the latter used as a proxy for severity.

Demographic information was also collected for participants. We included the following factors as covariates due to their frequent links to mental health disorders or substance misuse: gender (not female/female); age (years); relationship status (not single/single); sexual identity (heterosexual/not heterosexual); employment (at least part time/less than part time); and education level (any tertiary qualification/no tertiary qualification).

Procedures

Structured, confidential, and anonymous interviews lasting approximately one hour were conducted face-to-face during April 2015 by trained research staff in a cafe convenient to the participant. Interviews yielded details of participants’ patterns of drug use, associated health, social and justice-related issues, and involvement with local drug markets. Participants were compensated AUD40 for their participation. The confidential, anonymous, and voluntary nature of the interviews was explained to all participants, who were provided with an information sheet and then provided written consent before commencement of the interview.

Statistical analyses

Participants reporting misuse of each class of pharmaceutical were compared to those who did not use that pharmaceutical. Differences in group means (e. g., mean age or K10 scores) were assessed by paired t-tests. Chi-squared tests were used to assess differences in demographic characteristics for users of each class of pharmaceutical. Logistic regression analyses were used to assess relationships between recent use of each class of pharmaceutical and mental health indicators, other than the total K10 score, for which linear regression was used. Models were adjusted for demographic covariates listed above. In sensitivity analyses, models were further adjusted for frequency of illicit psychostimulant use. Analyses were conducted in Stata 13 (StataCorp, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Recent illicit or extra-medical use of pharmaceuticals was common in this sample: 51% reported extra-medical consumption of any pharmaceutical in the last six months (Table 1). The most commonly used were pharmaceutical stimulants (31%, including dexamphetamine, methylphenidate, and modafinil), benzodiazepines (27%), opioids (10%), and OTC codeine preparations (16%). Those reporting misuse of opioids, benzodiazepines, and antipsychotics were more likely to be male than those who did not, stimulant users were more likely to be non-heterosexual than non-stimulant users, opioid and antidepressant users were more likely to be unemployed than those who did not use those substances, and OTC codeine users less likely to have a post-school qualification than non-OTC codeine users. Illicit use of pharmaceuticals was likely to have begun after the age of 18 and use of individual classes of pharmaceutical tended to be less than monthly. Those who reported recent misuse of any of the above pharmaceuticals, used psychostimulants more frequently (p < .01, data not shown) compared to those who did not.

Table 1 Characteristics of RPU who reported recent illicit use of pharmaceutical medications, 2015

Note: Age of initial use is the age at which psychostimulant use was reported to commence; Used ≥ monthly use refers to the frequency of use of any psychostimulant; Unemployed = employed less than part-time; Tertiary = completed a qualification after completing high school; All RPU = the total group of regular psychostimulant users comprising this sample; †Any pharmaceutical refers to pharmaceutical stimulants or OTC codeine or other opioids or benzodiazepines or antidepressants or antipsychotics; * indicates that χ2 test showed a significant difference (p <.05) from the total sample for users of that substance for that characteristic.

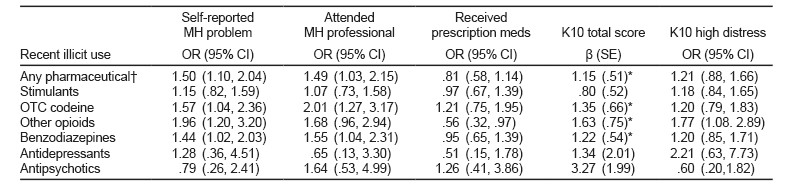

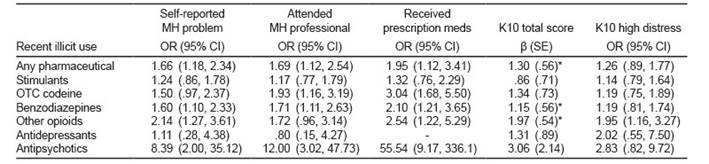

Over one-third (36%) of RPU in this sample reported having experienced a mental health problem during the previous six months. After accounting for demographic factors, this was more likely for those who had recently misused opioids, benzodiazepines, or OTC codeine (Table 2). Those who had misused benzodiazepines or OTC codeine were also more likely to have attended a MH professional during the last six months (OR 1.55; 95% CI = 1.04, 2.31 and OR 2.01; 95% CI = 1.27, 3.17, respectively). Of those receiving medications for their MH problem, most prescriptions were for antidepressants (70%). Other medications included benzodiazepines (28%), antipsychotics (14%), mood stabilizers (8%), and stimulants (6%). Total Kessler 10 scores were significantly increased for RPU who reported recent illicit use of OTC codeine (β = 1.35; SE = .66), opioids (β = 1.63; SE = .75) and benzodiazepines (β = 1.22; SE = .54), but not for those who reported misusing antidepressants, antipsychotics or pharmaceutical stimulants. High or very high distress (K10 > 21) was significantly more likely among those who had recently misused opioids (OR 1.77; 95% CI = 1.08, 2.89) than those who had not. Adjustment of these relationships for frequency of psychostimulant use did not account for these relationships (Supplementary Table 1). Small sample size precluded the assessment of potential links between frequency of illicit antidepressant use and receipt of medications for mental health problems.

Table 2 Associations between recent illicit use of pharmaceuticals and mental health indicators in RPU

Note: MH = mental health; K10 = Kessler 10 scale of psychological distress: High distress = K10 > 21; †Any pharmaceutical refers to pharmaceutical stimulants or OTC codeine or other opioids or benzodiazepines or antidepressants or antipsychotics; Use of each pharmaceutical was modelled separately for each mental health indicators (i.e. each cell above represents a separate model); all models were adjusted for age, gender, sexual identity, unemployment and frequency of ecstasy/related drug use; *p < .05.

Supplementary Table 1 Associations between recent illicit use of pharmaceuticals and mental health indicators in RPU, adjusted for frequency of illicit psychostimulant use

Note: MH = mental health; K10 = Kessler 10 scale of psychological distress: High distress = K10 > 21; Use of each pharmaceutical was modelled separately for each mental health indicators (i.e. each cell above represents a separate model); all models were adjusted for age, gender, sexual identity, unemployment and frequency of illicit psychostimulant (ecstasy/related drug) use; *p < .05.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The overall prevalence of pharmaceutical misuse is high (51%) in this sample of regular psychostimulant users, with significant increases in the use of pharmaceutical stimulants and OTC codeine compared to reports in the previous year (p < .05 for both) (Sindicich & Burns, 2015). It is also higher than for the general Australian population, where among 20-29 year olds (the closest group in age to this sample) only 5.7% reported illicit use of any pharmaceutical in the past year (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017). The use of individual pharmaceuticals by our RPU tended to be less than monthly, which was similar to use by the general population (54% used less than monthly) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017), but less frequent than their use of ecstasy tablets, and was linked to more frequent use of ecstasy and other illicit psychostimulants.

Even after accounting for stressors such as unemployment, non-heterosexual identity, and un-partnered relationship status that are frequently associated with mental health problems in this sample, participants reporting extra-medical use of pharmaceuticals appear to be at heightened risk of a range of mental health problems and increased levels of psychological distress. These problems may be severe, as suggested by greater attendance at mental health professionals. Receipt of mental health medication was not significantly related to misuse of the pharmaceuticals, and the pattern of medications received did not align with those misused, suggesting that the visits to MH professionals were not likely to be “doctor shopping” for illicit use (Maxwell, 2011; Worley, 2012). These potential harms were not accounted for by increased frequency of psychostimulant use, suggesting there may be a role in the mental health problems that is specific to the polypharmacy reported by regular “recreational” drug users (Kelly, Wells, Pawson, LeClair, & Parsons, 2014; Smith, Farrell, Bunting, Houston, & Shevlin, 2011; Wilkins et al., 2011).

Those who regularly use psychoactive substances, such as ecstasy and related drugs, tend not to view their illicit substance use as problematic, typically not seeking help from treatment professionals, and may view use of commercially formulated pharmaceuticals as less risky again, particularly given the occasional nature of the use as reported here. Despite this, the increased likelihood of mental health problems from the combination of substances is evident from our findings and those of some others (Lubman, Allen, Rogers, Cementon, & Bonomo, 2007; Medina & Shear, 2007), but is recognised as a gap in the overall literature (Kaye & Darke, 2012).

This study provides a unique insight into patterns of mental health among regular psychostimulant users who also misuse pharmaceuticals, but must be considered in light of some limitations. The study uses a sentinel non-representative sample drawn from jurisdictions across the country, providing information from a range of contexts, and use of this sentinel population of regular psychostimulant users provides timely information on the emergence of new trends and emerging potential harms that is not possible from larger nationally-representative studies. Thus, generalisation of our findings must be undertaken with some caution. Additionally, although our sample is based in Australia, similar patterns of psychostimulant use exist among young people in many countries, and the emergence of pharmaceutical misuse is worldwide (International Narcotics Control Board, 2016). Our mental health indicators are not clinical, and so cannot provide mental health diagnoses, but they do provide a measure of distress and indications of the severity of problems experienced by participants, with the Kessler 10 scale well characterised in drug using populations (NSW Government, 2015). Likewise, our measures of substance use rely on self-report, but these have been found to be robust among substance-using populations where data collection methodologies have appropriately addressed issues of anonymity and confidentiality (Queensland Government, 2017).

In conclusion, our findings shed light on the potential harms associated with the emerging issue of pharmaceutical misuse in a group of substance users who do not generally consider their use as problematic, and so may not interact with substance use treatment services. Mental health service providers should consider screening for extra-medical pharmaceutical misuse, particularly in patients such as young adults who are likely to use psychostimulants. Policy makers should also be aware of the potential link between extra-medical use of pharmaceuticals, including non-prescription medications, and mental health problems. Further research should also investigate links between intensity of illicit pharmaceutical use and mental health problems in regular users of psychostimulants.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)