Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are now the main causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1However, acute infectious diseases still occur in developing countries, predominantly affecting the most vulnerable social and demographic groups such as children under five years old and the elderly.2

Despite improvements in sanitation and hygiene interventions, safe water, promotion of exclusive breastfeeding, availability of oral rehydration salts (ORS), and vitamin A supplementation, acute diarrheal disease (DD) remains the second underlying cause of death in young children worldwide.3,4,5,6Each year, DD claims the lives of 525 000 children under five years,3 80% of which occurs in the first two years of life.7

Rotavirus is a leading etiologic cause of severe DD in young children, causing more than 215 000 deaths each year throughout the world8 and 40% of DD hospitalizations.9,10As a result, the rotavirus vaccine was introduced in 2006.11,12

In Latin American countries, there was a marked decrease in DD mortality between 1980 and 1990.13In Mexico, a reduction of 81.5% was observed between 1990 and 2000 (125.3 and 23.2 per 100 000 children under five years, respectively).14Still, a significant number of DD cases are registered.7

According to National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012 (Ensanut 2012 by its Spanish acronym), 11% of children under five years had DD episodes in the two weeks prior to the application of the survey; 53.7% were male, 21.0% were infants, and 54.8% were between one and two years old.15DD prevalence decreased from 13.1% in 2006 to 11.0% in 2012.16

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of morbidity and mortality due to acute DD in Mexico between 2000 and 2016, using secondary data sources, to understand its magnitude, distribution, and evolution.

Materials and methods

We carried out a longitudinal ecological study

The Mexican Health System

Access to healthcare in Mexico is conditioned by employment status. For the population with social security (PWSS), which includes employees in the formal economy, government employees, and their families (about 50% of the Mexican population), healthcare is provided by the social security institutions (SSI). Meanwhile, for the population without social security (PWOSS), which includes the self-employed or unemployed, healthcare is provided by the Ministry of Health and State Health Services (SS/SESA). Starting in 2003, people affiliated to Seguro Popular(SP) also received healthcare from the SS/SESA.

Sources of information

We analyzed DD epidemiological surveillance data, health services records, outpatient care records, hospitalization discharges, emergency services records, and mortality records. All data included year of occurrence and cause. Additional data included age, which was divided into large groups (infants: under one year, one to four years, children under five years (inclusive of infants), five to 64 years, and 65 years and over); sex; state of residence (n=32); and institution providing health care, which we analyzed as a dichotomous variable: “1” indicating the public SSI and “0” the SS/SESA. Inclusion criteria were: registers occurring between 2000 and 2016 and DD as the underlying cause coded by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10 codes A00-A09, including A09X).17

Epidemiological surveillance is carried out by the General Directorate of Epidemiological (DGE) Surveillance of the SS, a Nationwide Health Information System to collect data on mandatory reporting health conditions, including DD. Data is collected on a predefined form at the point of services by health care providers according to ICD-10 classification. This information is published weekly on the Epidemiological Surveillance Bulletin (BVE).18 We present here annual accumulated data.

Data were available for only some ICD-10 codes, place of residence (state), and sex (since 2004). Available tables included all DD ICD-10 codes: intestinal infectious disease (A00-A09 include A09X), cholera (A00), typhoid fever (A01.0), paratyphoid fever (A01.1-A01.4), other Salmonella infections (A02), shigellosis (A03), other bacterial foodborne intoxications (A05), intestinal amoebiasis (A06.0-A06.3, A06.9), amoebic liver abscess (A06.4), other protozoal intestinal diseases (A07.0-A07.2, A07.9), giardiasis (A07.1), rotaviral enteritis (A08, used since 2014), and intestinal infections by other organisms and the ill-defined (A04, A08, A09; except A08.0). Unfortunately, health care providers are not well trained in ICD-10 coding, and because this information is collected during the service and confirmatory tests are seldom available, physicians are prone to classify most DD as intestinal infections by other organisms and the ill-defined.17

Emergency data was only available for SS/SESA managed health facilities for the period 2007 to 2016.19 Data on emergency services is produced by health care providers at the point of care and collected at the patient level through a nominal information system.

Data on outpatient care is produced by healthcare providers at the point of care and collected through the Health Information System (SIS), an aggregated numerical system managed by the General Directorate for Health Information (DGIS). This database is publicly available through the DGIS data portal in dynamic tables for the years 2000-2016.20,21

The hospital discharge database is managed by the DGIS and contains patient level information of all hospital services provided by the public health sector for the years 2004-2015.20,22A more complete data set (2000-2016) is available for hospitals managed by the SS/SESA.19

Mortality data is collected through a nationwide system managed by the National Institute of Geography and Statistics (INEGI by its Spanish acronym) and published by the DGIS in dynamic tables ;23 data is available from 2000 to 2016.

Population data was obtained from the DGIS data portal and included : a) general population estimates made by the National Population Council (Conapo) from 1990-2030,24 b) data on population access to Social Security25 and c) births estimates made by Conapo.26

Data analysis

We calculated measures of DD frequency; outpatient, emergency, and hospitalization attendances rates; as well as the DD mortality rate. Where possible, data was disaggregated by sex, age group, place of residence (state), and access to social security institutions. Corresponding subpopulations were used as the denominator. We present graphical and tabular results at the national level and maps at the state level.

Emergency department data analysis

We calculated the emergency department attendance rate by dividing the total number of emergency department attendances to SS/SESA by the total PWOSS. Mortality rates in the emergency department were calculated using the number of DD deaths registered in the emergency department as the numerator and all DD emergency admissions as the denominator, annually. The rate of referral from the emergency department to hospitalization was calculated by dividing the number of patients referred to hospitalization by the total number of DD emergency admissions, per year.

Outpatient attendances data analysis

According to availability of information, it was only possible to calculate the outpatient attendances rate for children under five years. The rate was calculated by dividing the total DD outpatient attendances by the total population under five years. The ratio of hospitalization by consultation was constructed using the total number of DD hospitalizations among children under five as the numerator and the total number of DD outpatient attendances among children under five as the denominator.

Hospitalization data analysis

The hospitalization rate was calculated using the number of DD discharges as the numerator and the respective population (with and without social security) as the denominator. The hospital mortality rate was calculated using the number of deaths due to DD in hospitalization as the numerator and the total DD discharges as the denominator.

Mortality data analysis

Mortality rates were calculated for the general population and sub-groups using appropriate population denominators. Infant mortality was calculated using live births as the denominator. We calculated the mortality rate ratio for some sub-populations, with 95% CIs to test for differences in mortality.We used MS Excel,* ArcGis‡ and Stata.§

Results

Epidemiological surveillance

Cases of DD in all ages in Mexico decreased from 6.9 to 4.8 million between 2000 and 2016; 54.9% were female. The rate declined 42.1% (table I) over this period. Causes of DD during the period were, primarily, intestinal infections by other organisms and the ill-defined (79.2%), intestinal amoebiasis (10.0%), typhoid and paratyphoid fevers (2.1%), other protozoal intestinal diseases (1.5%), other bacterial foodborne intoxications (0.5%), giardiasis (0.5%), shigellosis (0.3%), and other Salmonella infections (0.2%).

Data available for rotavirus (2014-2016) showed a 48.5% reduction in the number of reported cases, with 1 299 cases in 2016. The highest incidences occurred in Chiapas (290 cases) and Baja California (213). Durango had only one registered case in two years.

Table I Estimated indicators for acute diarrhea disease by source information, Mexico 2000-2016

| General | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | Indicator | Year | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Epidemiological Surveillance | Epidemiological Surveillance Incidence Rate§ | 683.0 | 676.5 | 660.6 | 591.2 | 561.8 | 551.8 | 531.8 | 504.0 | 494.2 | 493.1 | 499.4 | 520.9 | 519.2 | 498.5 | 455.2 | 447.1 | 399.6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Emergency Department* | Emergency Department Admission Rate§ | 40.4 | 47.8 | 59.3 | 69.4 | 78.3 | 87.6 | 80.9 | 80.5 | 83.3 | 81.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emergency Department Mortality Rate§ | 2.7 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emergency Department Reference to Hospitalization Rate‡ | 12.4 | 9.6 | 6.0 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 4.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outpatient Care | Outpatient Care Rate‡ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hospitalization by Consultation& | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hospital Discharges | Hospitalization Rate§ | 7.1 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 7.2 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 4.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hospital Mortality Rate‡ | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mortality | Mortality rate# | 5.2 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Infant Mortality Rate(< 1 year old)# | 77.9 | 66.5 | 63.3 | 58.3 | 50.5 | 52.3 | 43.8 | 42.7 | 31.7 | 27.8 | 26.1 | 25.0 | 25.2 | 27.9 | 23.3 | 20.0 | 21.6 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Children under five years | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source | Indicator | Year | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Epidemiological Surveillance | Epidemiological Surveillance Incidence Rate§ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||||||||||||

| Emergency Department* | Emergency Department Admission Rate§ | 149.0 | 175.5 | 200.6 | 234.1 | 250.5 | 283.8 | 255.9 | 250.3 | 254.2 | 264.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emergency Department Mortality Rate§ | 2.8 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emergency Department Reference to Hospitalization Rate‡ | 14.5 | 10.5 | 6.7 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 4.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outpatient Care | Outpatient Care Rate‡ | 15.9 | 11.1 | 9.8 | 8.6 | 11.6 | 12.3 | 13.0 | 12.7 | 12.8 | 12.1 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 11.9 | 14.4 | 9.3 | 11.4 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hospitalization by Consultation& | 3.0 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 1.6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hospital Discharges | Hospitalization Rate§ | 34.4 | 41.0 | 37.3 | 42.7 | 37.5 | 26.8 | 23.6 | 22.4 | 25.0 | 22.5 | 19.4 | 18.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hospital Mortality Rate‡ | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mortality | Mortality rate# | 21.8 | 19.0 | 18.6 | 17.5 | 15.6 | 16.2 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 10.5 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 8.4 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 7.3 | ||||||||||||||||||

* SS;

‡Rate per 100;

§Rate per 10 000;

#Rate per 100 000;

& Ratio

Source: DGE, SS. Epidemiological Surveillance in Mexico, 2000-2016.18 DGIS, SS. Dynamic table of Emergency departments, México, 2007-2016.22 DGIS, SS. Dynamic table outpatient care services, Mexico, 2000-2016.23 DGIS, SS. Dynamic table by hospital discharges, Mexico, 2000-2016.19 INEGI, DGIS. Dynamic table by mortality, Mexico 2000-2016.21 Birth’s Projections in Mexico 1990-2030. Conapo, DGIS. Population’s Projections in Mexico, 1990 - 2030.26

DD attendance to emergency departments

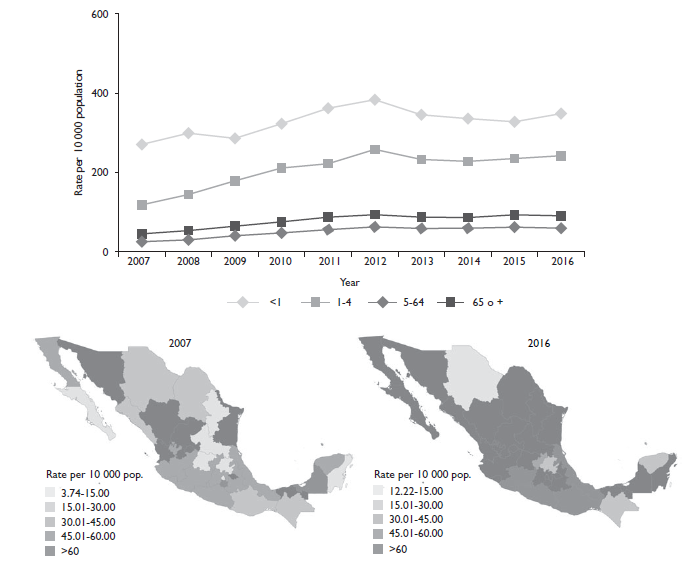

The Mexico SS reported 547 790 DD emergency department attendances, equivalent to 81.8 per 10 000 PWOSS in 2016. Until 2012, there was a steady increase in the number of emergency department attendances, up to 87.6/10 000, and the rate remained stable around 81/10 000 thereafter. Again, a greater proportion of patients (56.1%) were female. When stratified by age group, emergency care was provided mainly to infants (an annual average of 32.8 attendances per 1 000 children under one year), followed by children 1-4 years of age (2.07 per 1 000 children 1-4). Elderly and adults were attended to a lesser extent (figure 1). Of all registered attendances, 5.2% were referred to hospitalization, while 1.5 out of 10 000 ended in death.

Source: DGIS, SS22 and Conapo, DGIS.26

Figure 1 Diarrheal disease attendance in emergency departments by state of residence and group of age. México, 2007-2016

Maps in figure 1 showed no spatial pattern to DD attendance in emergency departments. In 2016, Colima reported the highest rate (46.6/1 000), followed by Coahuila (28.7/1 000) and Campeche (18.5/1 000). In contrast, the lowest rates were found in Chihuahua, Chiapas, Hidalgo, and Yucatan, where less than 3/1 000 population attended the emergency department for DD.

Emergency attendance due to rotavirus reduced by 77.7% during the period, from 1.8/100 000 population in 2007 to 0.4/100 000 in 2016, with no apparent spatiotemporal pattern.

DD attendance in outpatient care

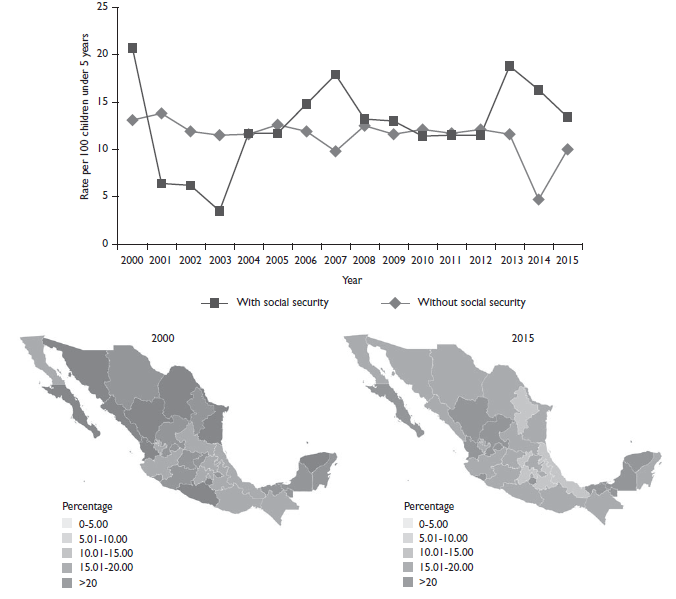

Total DD outpatient attendance in children under five years decreased by 31.8% in the 2000-2015 period. In 2000 there were 1.8 million attendances recorded, while in 2015 the attendances were 1.3 million. The outpatient attendance rate due to DD in children under five years decreased by 28.4% between 2000 and 2015. In 2011 we found a large inconsistency in data for IMSS-Prospera: the number of outpatient consultations was 3 287 323, which was clearly an outlier, so we imputed the data for this year by taking the average of the adjacent years (figure 2).

Source: DGIS, SS22 and Conapo, DGIS.26

Figure 2 Diarrheal disease outpatient attendances rate in children under five years old by state of residence and social security condition. México, 2000-2016

Data on outpatient attendance in SSI also showed inconsistencies throughout the study period (figure 2), therefore we decided not to interpret it and only present data on outpatient care services provided by SS/SESA. Campeche, Durango, and Nayarit had the highest DD outpatient attendances in children (140.6, 139.5, and 134.1 attendances per 1 000 children under five years, respectively). There is an overall slight decreasing trend in outpatient services provided by SS/SESA.

By cross-referencing outpatient services and hospitalization data in children under five years we found that, on average, there were 2.4 DD hospitalizations for every 100 DD outpatient consultations, with a decreasing trend over the study period.

DD hospitalization

The DD hospitalization rate reduced by 37.6% during the period; 50.3% were male. The DD hospitalization rate was 50.2/10 000 among infants, 24.1/10 000 among children 1-4 years, 3.1/10 000 among the population 5-64 years, and 11.1/10 000 among the population over 65 years. We observed a decreasing trend in all groups, starting in 2007.

The DD hospitalization rate was higher in PWSS (58.8%). The trend decreased by 49.5% from 2004 (10.9/10 000) to 2015 (5.5/10 000). In PWOSS, the magnitude of the decreasing trend was smaller (21.1%) from 2000 (4.6/10 000) to 2015 (3.6/10 000). Overall, Coahuila, Yucatán, and Sinaloa reported the highest DD hospitalization rate (8.8, 8.4, and 8.2 discharges per 10 000 population) (figure 3).

Source: DGIS, SS25 and Conapo, DGIS.26

Figure 3 Hospitalization rate due to diarrheal disease by state of residence and social security condition. México, 2000-2016

The DD hospital mortality rate increased by 53.3% between 2004 and 2015, from 0.6 to 1 deaths per 100 discharges.

Hospital discharges for Rotavirus decreased from 522 records in 2004 to 122 in 2015, representing 9.3 and 2.2% of all DD discharges, respectively. The higher percentage of deaths were among males (58.3%). Between 2004-2015, a total of 2 886 (51.2%) discharges were among children 1-4 years and 2 189 (38.8%) were among infants. These rates showed a decreasing trend over the period; in infants the rate decreased from 9.4/100 000 in 2004 to 2.1/100 000 in 2015, and in children 1-4 years the rate decreased from 2.7/100 000 in 2004 to 0.7 /100 000 in 2015.

The median hospitalization rate due to rotavirus in children under-five years old decreased 59.1% after the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine. The median rate in the pre-vaccine era (2004-2006) was 5.2 hospitalizations per 100 000 children under-five years old while (table I), the rate was 2.1/100 000 in the postvaccine era (2007-2016).

Rotavirus hospitalizations were more common in PWOSS (76.4%). Chiapas and Guanajuato had the highest rate in 2015 (12.2 and 5.0 per million population, respectively) and 17 states did not report a case. In hospital mortality due to rotavirus was 0.3% (19).

DD Mortality

Between 2000 and 2016, 66 849 people in Mexico died whose underlying cause of death was diarrhea. In this period, DD-specific mortality decreased by 39.7%. Mortality was higher in males at the beginning of the time series, however in 2008 the trend changed and females had the highest mortality rate from then until 2016 (figure 4). As the map shows, southern states had the highest mortality rates due to DD. Throughout the time series, Chiapas had the highest DD mortality rate; its peak value was in 2001 (14.4 deaths per 100 000) and its lowest was in 2011 (8.4/100 000).

Source: INEGI, DGIS 21 and Conapo, DGIS.26

*Per 100 000 births

Figure 4 Diarrheal disease mortality rates by sex, age group, and state of residence. México, 2000-2016

According to age group, the highest risk of death by DD was in children under five years. In 2000, the risk of death by DD in infants was 63.9 times higher than in the population aged 5-64 (95%CI 59.2 - 68.9), though this ratio decreased to 23.5 in 2016 (95%CI: 21.0 - 26.2). The largest decrease occurred in infants; the infant mortality rate decreased by 72.3% between 2000 and 2016. As of 2010, the infant mortality rate due to DD became very close to the mortality rate of elderly people. The mortality rate in people over 65 years was the highest between 2014 and 2016.

There were differences in DD mortality according to the health coverage status. Between 2000 and 2016, PWSS had an average annual mortality rate due to DD of 2.3 deaths per 100 000 population, compared with PWOSS, who had an average annual mortality rate of 4.5 deaths per 100 000 population (almost twice, 95%CI 1.90 - 1.97). However, the gap was closed, such that the risk of dying due to DD decreased from 2.6 (95%CI 2.4 - 2.7) in 2000 to 1.2 (95%CI 1.1 - 1.2) in 2016, comparing people with and without social security. Among PWOSS, DD mortality decreased rapidly until 2009, after which the rate has remained almost unchanged.

There were 180 recorded deaths due to rotavirus during the study period. The average annual rate was one death per 100 000 population; this rate decreased by 76.4% over the period (from 1.4/100 000 in 2000 to 0.3/100 000 in 2016). The trend was similar by sex, though slightly higher among males (average annual rate 1.2 vs 0.8/100 000). The majority of rotavirus deaths occurred in infants (65.6%), followed by children between 1-4 years (27.2%). Once again, PWOSS had 5.6 times the risk of dying by rotavirus compared to PWSS (95%CI: 3.6 - 8.7). According to the state of residence, Colima and Veracruz had the highest rotavirus mortality (23.1 and 13.0 /10 million population).

Discussion

In this paper, we reviewed all sources of administrative records and population projections in order to analyze the magnitude, distribution and evolution of acute diarrheal diseases (DD) in Mexico from 2000-2016. Among our main results, we found an important decrease in the number of DD events reported in the Epidemiological Surveillance System, which was correlated to a decrease in the DD outpatient attendance rate in children under five years, as well as in the DD hospitalization rate. Although DD mortality decreased considerably, DD emergency department attendances doubled during the 2007-2016 period and hospital mortality due to DD increased.

Our study showed that DD mortality in children under five years of age has steadily and substantially decreased in Mexico between 2000 and 2010, and has remained almost constant until 2016. This trend could be attributed to the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine throughout the country between 2006 and 2007.12 The vaccine has had an efficacy of 85% against rotavirus-related disease and hospitalization 27 which is consistent with the decrease in hospitalizations and deaths due to rotavirus demonstrated in this study. In Mexico, the introduction of the rotavirus vaccine reduced overall DD hospitalizations in children under five years of age by 47%. 28 Consistent with this previous research, we also observed a 59.1% reduction in the hospitalization rate due to rotavirus.

As reported by the literature, the factors that have contributed to the decrease in DD mortality in Mexico have been, mainly, the distribution and widespread use of ORS; the program Piso firme;15,29the increase of exclusive breastfeeding; an improvement in nutrition, sanitation, and hygiene conditions; vaccination against rotavirus and measles; and Zinc supplementation.5,30,31

Our data suggest an important increase in emergency health services utilization, in concordance with official norms and programs launched by state and federal health authorities,32,33as well as an important decrease in the DD mortality rate in the emergency services. The observed decrease in the DD mortality rate in emergency departments reflects improvements in diarrheal management and treatment in this area.

Paradoxically, there was a 66.7% increase in hospital mortality due to DD. This could be the result of a better handling of DD patients in the emergency room, such that only the most severe cases are referred to the hospitalization area. This had the effect of reducing the total number of hospitalized cases (denominator), but not the actual number of deaths (numerator).

Chiapas and Oaxaca had the highest diarrhea mortality rates among the states of Mexico during the entire period, which could be an indicator of gaps in the social determinants of health and a reflection of inequity. It should be mentioned that, although Guerrero does not appear among the states with the highest mortality due to DD, an analysis of under-registration carried out in 201834 showed Guerrero as one of the territories with the highest DD mortality rates in the country. Additionally, the population without social security had a higher DD mortality compared to the population with social security, which points again to social inequalities in health.

Lack of accessibility to health services is still a barrier that can have a significant impact on occurrence of deaths due to diarrhea,35 so it is crucial to achieve universal access for the Mexican population. Future research should focus on analyzing the increase of emergency department attendances. A second issue was the increase in hospital mortality due to DD. Despite the substantial reduction in DD morbidity and mortality, 3 843 people in Mexico died due to DD in 2016, even though it corresponds to one of the Sustainable Development Goals,36and there are well-known and low-cost interventions for its treatment. DD mortality magnitude is an indicator of inequality in the social determinants of health, and the elimination of all avoidable differences among social groups should be an ethical imperative for the benefit of the Mexican population.

Limitations

This study has several limitations, including those of an observational study with secondary data sources. We used public information which, despite undergoing periodic quality assurance by each responsible institution, showed some inconsistencies. For example, data on outpatient consultation for Social Security Institutions had outliers which precluded its use. Another important limitation was the lack of available epidemiological data in usable format. Epidemiological data should be publicly available in database format, disaggregated by age group and sex. The available epidemiological surveillance data was further limited by the high number of cases classifed as intestinal infections by other organisms and the ill-defined, which could impact in the estimation of cause-specific DD. Another consideration may be the underreporting of deaths, which is about 5% in Mexico and most prevalent in infants and under five years in marginalized areas (unpublished data). In a study reported in 2012, researchers found 22.6% underreporting in children under five years old. However, this study was carried out in a representative sample of the 101 municipalities with the lowest Human Development Index,37where underreporting is more prevalent than in the current study.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)