BACKGROUND

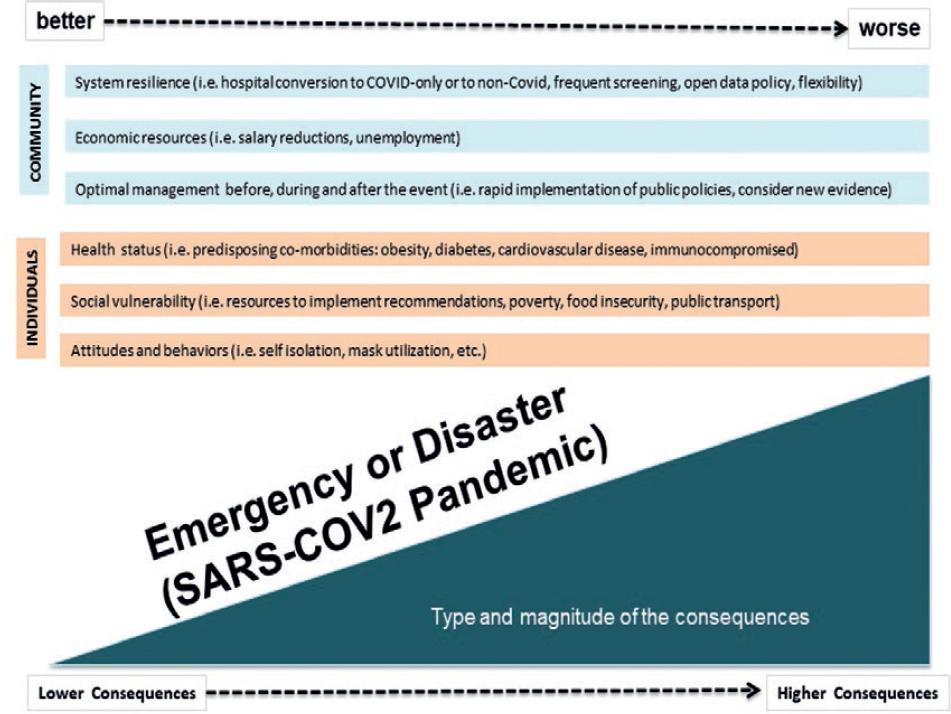

The coronavirus (CoV) disease (COVID)-19 pandemic has strained resources, forcing health-care professionals and society to change paradigms. For example, physicians are forced to diverge even the sickest patients away from hospitals, and society is demanding strict public health measures that may infringe on the fundamental human rights of freedom and autonomy. It may seem like a lose-lose situation, and resolutions take a lose-least approach contemplating different ethical principles. However, while medical care ethics emphasizes the individual, focusing on the patients autonomy and the cure and treatment of health conditions, public health ethics emphasizes the greater good of a population or community and the pursuit of collective action. These ethical frameworks contrast with the well-established ethical principles in research of Beauchamp and Childress1-3, whose goal is to produce evidence to advance the greater good (Table 1). The following paper describes the ethical challenges the medical community, society, and public health systems face under the COVID-19 pandemic and the moral duty to follow (Fig. 1).

Table 1 Ethical differences between public health and biomedical research

| Ethical topics | Emergency or disaster public health | Biomedical research |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Focus on emerging or existing health problems | Focus on research involving human subjects |

| Intent or purpose | To prevent or control disease or injury and improve health | To generate or contribute to generalizable knowledge |

| Informed consent | Often considered not necessary | Basic tenant |

| Ethics guidelines | Standard guidelines are relative to the magnitude of the public hazard | Ethical guidelines are well-established and are subject to independent ethics reviews |

| There are numerous resources available for guidance (Nuremberg Code, Declaration of Helsinki, etc.) | ||

| Context | The context is disruptive by nature and often in places with limited resources that creates a state of urgency | Most of the times the context is stable with adequate resources |

| Ethical tenants | Duty to care | Autonomy |

| Duty to steward resources | Beneficence | |

| Duty to plan | Non-maleficence | |

| Distributive justice (allocation protocol that is consistently fair) | Justice1 | |

| Transparency (make the protocol clear to everyone)2 |

CHALLENGES IN HOSPITAL ADMINISTRATION AND MEDICAL CARE

Resuming normal activities during or immediately after the pandemic has been arduous. Hospitals have risks of cross-contamination. There is shortage of beds, personnel, and resources. Patients admitted to the hospitals remain isolated, for fear of viral transmission, either to the visitors or from them. Bacterial resistance is increasing due to the use and abuse of antibiotics. Furthermore, additional medical consultations may not be available.

Ambulatory procedures are also challenging. Clinics need significant adjustments to keep clean spaces and to prevent overcrowding on the waiting rooms. As a result, fewer consultations are given per day, increasing the hurdles to get specialized care.

There is also the question of how to maintain underutilized staff during the ongoing pandemic surge4. There have been some reports of health systems cutting their salaries or repurposing them to other activities. Finally, if medical and health staff becomes infected, there is an ethical dilemma if the person should be treated differently (i.e., given preference for treatment or resources) or if the institution should cover medical attention or funeral costs.

Possible measures to lessen risks

The physical and psychosocial harm posed by lockdown must be balanced against the potential benefits of the standard of care in a case-by-case basis

Before harm and benefits can be balanced, they must first be identified. A relative weight must be given to each harm and gain depending on the context and resource availability

The stay of patients in medical units should be minimized without altering the quality of care

Safe communication between hospitalized patients and family members must be priority

Several institutions like the Cleveland Clinic have published ethical guidelines, treatment priorities, and procedure manuals to prevent discrimination and avoid delays in medical care5.

CHALLENGES IN THE POLICIES TO REDUCE SEVERE ACUTE RESPIRATORY SYNDROME-CoV (SARS-CoV-2) TRANSMISSION

Ideally, during the pandemic, non-COVID-19 patients should attend the hospital only if they need urgent care. However, on the one hand, many of these patients are also the most vulnerable to develop severe COVID-19. On the other hand, this has generated an enormous delay in treating other serious urgent conditions. Health-care providers should keep in mind that the pandemic is responsible for non-COVID-19 lives as well6. Now, non-COVID-19 gray areas are becoming available in some institutions. Still, it is difficult to decide which patients should receive priority for proceedings with regard to medical attention or surgery within a slowly, staged fashion return to normal activities. At present, most institutions are not prepared to establish a new model of care for the new normality.

Disclosure of positive cases can also be an ethical dilemma. Privacy issues may limit efforts to stop the spread of the pandemic. Patients may claim their right to keep their health information confidential, exposing health care workers to acquire the disease, and limiting information to find potentially infected contacts. Some governments have developed phone applications that trace potential contacts with COVID-19 cases and inform possible contacts. However, concerns about collecting sensitive information without specific permission may cause ethical dilemmas7. Furthermore, access to information (i.e., areas with the most significant number of cases or hospital outbreaks) may cause anxiety or fear.

The cost that the pandemic is inflicting over the health-care system is also a topic to discuss. Health care workers and individuals with potential professional exposure to acquiring the disease need protection materials and equipment. Still, the budget may not be enough to provide the best protection equipment possible for everybody. Public health officials may confront difficult decisions to distribute resources with fairness when supplies become scarce. In addition, private institutions may be transferring the costs of the equipment to the patients, with a respective profit as well8.

Possible measures to lessen risks

Screen COVID-19 asymptomatic infection before any scheduled admission to the hospital by polymerase chain reaction and, in emergency cases, with pulmonary computed tomography scan

Design strategies to mitigate harm when surgery must be delayed. These include lifestyle or pharmacological measures6

Always respect the principle of autonomy, which gives weight to an individuals freedom to choose between the risks of the circumstances or the need to get individual medical attention

All health systems should endorse an open data policy to keep everybody informed about the potential risk of acquiring the disease

All tracing COVID-19 apps should fulfill four principles: they must be necessary, proportional, scientifically valid, and time bound. Information should not be stored centrally after the outbreak is under control9

Implement training for the ethics committee members about the handling of ethical dilemmas during the health crisis.

CHALLENGES IN MEDICAL ATTENTION

Telemedicine, as the available option to adopt, has its drawbacks. Through any electronic media, doctors embrace the challenge to understand the message beyond the words by neglecting the analysis of the voice tone and the facial or corporal expressions10. Even when having face-to-face interaction at the hospital, SARS-CoV-2 fabricated barriers between physicians and patients. First, because the time spent with patients must be minimized, and second, because physicians and nurses must wear physical protection making human contact a luxury. The gaps in doctor-patient relationships have widened, mainly, in the most vulnerable patients, precisely because of their fragile condition. Additional efforts need to be made to understand patients fully.

CHALLENGES IN PUBLIC HEALTH POLICIES

Difficult ethical dilemmas arise when migrating from medical care or biomedical research to the public health arena. Public health measures to protect the greater good for society may interfere with individual rights and liberties. If there is a reasonable scientific probability that an individual is infected and becomes contagious, it might be argued that the state has the attribution (moral and sanitary) to submit him or her to quarantine. If so, hospitals could be obligated to disclose the information of each positive case. But to infringe liberty to prevent individuals from infecting others, even when calls for voluntary quarantine were not obeyed, it is a violation of the patients autonomy. To grant permission to disclose his or her information violates the principle of privacy.

Other interventions grounded on arguments of the greater good are also controversial if weighted against an individual or social harm, that is, the obligation to use masks. If society is coerced for its benefit, it can establish precedents to also demand similar public measures in other controversial health situations, such as mandatory vaccination or sterilization.

Possible measures to lessen risks

When stakes are high, and the most significant damage is preventable, protection of autonomy must be balanced against public health. To justify such types of violations, several factors must be considered, such as a very high degree of transmission, a short length of quarantine, and extreme risk or public health benefits

Coercion must also benefit those who are coerced, as much as to society as a whole

Plans for coercive measures should ensure safe, habitable, and human conditions of confinement, including basic needs

Vulnerable groups of the society warrant special protection. There must be a clear identification of the most vulnerable population and a plan to minimize the risks

Liberty should not be infringed to a greater extent than the necessary to achieve the public health goal

Society should give something back to those at a disadvantage. If society benefits from liberty infringement, compensation should be given to those who suffer the burdens.

CHALLENGES IN BALANCING RESEARCH AND CLINICAL CARE

Although the article deals with ethical problems in patient care during COVID, we are aware that it is also generating bioethical problems in research. Covidization of research has increased the number of studies on the pandemic topic11. As a consequence, resources, and its potential benefits for other patients, have been diverted. In some instances, this has led to redundancy and wastage of means, and the risk of neglecting optimal care on other important topics, such as highly prevalent or emerging diseases.

Ultimately, lockdown is needed to reduce the risk of contracting COVID-19 but will also result in the cancellation of imperative medical interventions, policy restrictions on visitations to hospitals, and alienation. Public health interest may override individual privileges, raising the question if the basic human rights such as autonomy and liberty are really absolute. Collateral casualties from the suspension of health-care activities may never be fully recovered. The principle of beneficence implies that what is good surpasses the bad. However, beneficence is difficult to estimate when harms, such as death and disease risks, are difficult to estimate. Bioethics grants the underlying principles used to navigate tough decisions, in this case, the COVID-19 pandemic.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)