Highlights:

Fertilization applied in Pinus patula, one year later, generate no differences for the variables studied.

Trees show differences in growth and biomass due to genetic group effect.

Significant interaction between genetic quality of trees and fertilization was observed.

Controlled-release fertilizer promoted growth of superior genotypes.

Prescribed fertilizer dose, based on foliar analysis, generated a non-optimal response.

Introduction

Pinus is the most used genus to establish commercial forest plantations worldwide (Comisión Nacional Forestal [CONAFOR] & Colegio de Postgraduados [COLPOS], 2009). Pinus patula Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham. var. patula, due to its high production capacity, it is important in countries of the southern hemisphere. (Dvorak et al., 2000); however, Mexico has a small planted area in spite of being the species' center of origin (Sáenz-Romero, Beaulieu, & Rehfeldt, 2011).

Water availability, light, climate, soil nutrients and individual genetics influence tree growth. The use of genetically superior trees with adequate nutrient management promotes performance of commercial forest plantations (Munsell & Fox, 2010) and it is a way to increase P. patula production in our country. Mexico reports advances in genetic improvement of P. patula by identifying more productive individuals or with higher wood quality (Bustillos-Aguirre, Vargas-Hernández, López-Upton, & Ramírez-Valverde, 2018; Valencia-Manzo & Vargas-Hernández, 2001), by establishing and studying the performance of new tree families selected in their natural range.

There are new technologies of improved effectiveness for plant nutrition such as controlled-release fertilizers, which are composed of traditional fertilizers coated with a polymer layer that, when wetted, are slowly released to the soil by diffusion, so that loss is minimized and time and energy required to be absorbed is reduced (Ali & Danafar, 2015; Chandra et al., 2019; Reyes-Millalón, Gerding, & Thiers-Espinoza, 2012). On the other hand, it has also been documented that inorganic fertilizers are effective in promoting P. patula growth (Lázaro-Dzul et al., 2012; Maliondo et al., 2005; Mavimbela, Crous, Morris, & Chirwa, 2018).

This experiment was designed to analyze the response of P. patula in productivity by combining genetic quality and nutritional condition in a progeny trial. The objective was to study the effect of traditional and controlled-release fertilizers, and of the doses defined technically or empirically, on the growth of 20 families of trees with different genetic quality, divided into a superior and an inferior group. The hypotheses were: 1) the effect of fertilizer doses defined by foliar analysis or empirical knowledge (based on previous experiments) is similar to each other; 2) the use of controlled release fertilizers and traditional agricultural fertilizers produces similar responses on tree growth; 3) growth initiation and cessation are influenced by fertilizer treatments; and 4) genotypic groups show similar responses to fertilizer application.

Materials and Methods

Study area

This experiment was conducted in a P. patula progeny trial established in September 2015 at the Agua Prieta property of the ejido Peñuelas Pueblo Nuevo, Chignahuapan, Puebla (19° 57’ 43’’ N, 98° 06’ 11’’ W, 2 555 m elevation). The climate is C(E)(w), semi-cold subhumid with summer rainfall, mean annual temperature of 13.5 °C and precipitation between 750 and 1 000 mm in the lower and upper parts, respectively (Pérez-Soto, Figueroa-Hernández, García-Núñez, & Godínez-Montoya, 2017). The soil is classified by INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2013) as Durisol and Andosol.

The progeny trial is composed of 20 blocks with 100 half-sib families planted in plots of one tree per family, randomly placed in a 3 x 3 m real frame. Each individual was part of a family of trees with outstanding phenotypic characteristics, selected in the forest belonging to the ejido (20° 00' 11” N, 98° 07' 48” W, 2 894 m elevation). When trees were 3 years old, they were measured and evaluated with an analysis of variance; block effect adjusted means (blocking the environmental factor) helped to determine genetic quality of each group of families (Salaya-Domínguez, López-Upton, & Vargas-Hernández, 2012). Ten families of superior and 10 of inferior genetic quality were selected for the experiment, according to height performance, to compare response to fertilization treatments applied.

Soil sampling and foliar analysis were performed as diagnostic in June 2018. Soil samples were obtained from the first 30 cm depth randomly in 12 blocks selected for the experiment (due to homogeneous drainage characteristics). Three composite samples were generated and analyzed according to NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales [SEMARNAT], 2002). Leaf samples from three genetically “superior” and three “inferior” individuals were found according to the methodology used by Wells and Allen (1985). Samples were oven-dried for 72 h at 70 °C, ground and analyzed. N concentrations were determined by the micro-Kjeldahl method and those of P, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Cu, Zn, Mn and B by coupled plasma induction optical emission spectrometry (Varian ICP OES 725-ES; Mulgrave, Australia), using digests with a mixture of H2SO4:HClO4 (2:1, v:v) (Alcántar-González & Sandoval-Villa, 1999).

Defining treatments

Treatment 1 corresponded to trees without fertilizer application, which were considered as controls. Treatment 2 or “technical” was defined by comparing the nutrient concentrations found in foliar analyses and critical concentrations reported by Sánchez-Parada, López-López, Gómez-Guerrero, and Pérez-Suárez (2018) for P. patula. To correct the deficiencies found, doses of 91 mL of Ca, 53 mL of Mn, 10 mL of Zn, and 5 mL of Fe were applied to the soil of each tree, using liquid fertilizers at concentrations of 10 %, 4 %, 8 %, and 8 % of those nutrients, respectively.

Treatment 3 was defined empirically based on other fertilization studies in related species and similar conditions (Reyes-Millalón et al., 2012; Štofko, 2010; Vázquez-Cisneros et al., 2018). The treatment involved the application of 20 g·tree-1 of a controlled-release fertilizer (percentage % by weight: N-NO3 = 5.80 %, N-NH4 = 6.60 %, P2O5 = 6.00 %, K2O = 12.00 %, CaO = 2.00 %, MgO = 3.50 %, Si = 2.10 %, S = 0.00 %, Fe = 0.40 %, Mn = 0.05 %, Cu = 0.04 %, Mo = 0.01 %, Zn = 0.06 % and B = 0.03 %, concentrations reported by the manufacturer), with a release time of six months depending on soil humidity and temperature.

Treatment 4 was established as a counterpart to the previous treatment, based on traditional agricultural fertilizers such as urea, phosphonitrate, magnesium sulfate, potassium nitrate and copper sulfate at doses of 4.32, 2.76, 2.46, 5.22 and 0. 04 g·tree-1, respectively; plus, phosphoric acid and liquid fertilizers of Ca at 10 %, Mn at 4 %, Zn at 8 % and Fe at 8 % at doses of 1.55, 0.87, 2.29, 0.13 and 0.24 mL·tree-1, respectively, to match the concentrations of the controlled-release fertilizer (excluding Si, Mo and B).

Treatments were applied in September 2018, randomized at the block level, so each treatment had three replicates. Each replicate included 20 families represented by a single tree. Treatments 2 and 4 were applied in solution, distributing them manually in the drip zone of tree crowns. Treatment 3 was applied in the same area, in the four cardinal points, placing the granules in a small opening at surface soil level, which was then covered.

Measurement of variables

The initial measurement of diameter at root collar (DRC, cm), diameter at 1.3 m height (DBH, cm), total height (TH, cm) and number of whorls (VERT) was made in October 2018. Diameters were measured using a Lufkin® diametric tape and height with a 5 m high Apex® stadia. The final measurement was made in November 2019.

Phenology was assessed in Julian days by determining the onset (YEMA_IN) in February (7, 11, 18 and 25) and the cessation of height growth (YEMA_F) in October (1, 11, 21 and 30) and November (14) 2019. Leaf sampling was done in November 2019 according to Wells and Allen (1985). The collected material was dried for three days in an oven at 70 °C and the mass of 100 needles (MASA_100, g) was obtained using a precision balance to hundredths of a gram (Chyo® JK-200, Chyo Balance Corp., Japan).

Other variables calculated were absolute growth rate (AGR) and relative production rate (RPR) for DRC, DBH, TH, VERT and biomass index [BI (dm3) = (DRC2 * TH)/1000] (Álvarez, Rodríguez, & Suárez, 1999), in addition to MASA_100, YEMA_IN and YEMA_F, using the formulas of Hunt (1990):

where,

AGR = average total increment for a defined interval

RPR = average relative production rate for a defined interval

W(1,2) = current and previous period's increment for the variable evaluated (DRC, DBH, TH, IB and VERT)

t(1,2)

Model and Statistical Analysis

The statistical model of completely randomized blocks allows identifying the effects of each factor and interaction between them, which corresponds to:

where,

y ijkl = value of the individual of the k-th family, within the j-th genotypic group, in the i-th block nested in the l-th fertilization treatment

µ = population mean

T l = fixed effect of the l-th fertilization treatment

B

i(l)

= random effect of the i-th block nested in the l-th fertilization treatment

G j = fixed effect of the j-th genotypic group of trees

TG jl = fixed effect of fertilization treatment and genotypic group interaction

RG

ijl

= random effect of interaction of replication and genotypic group

F

k(j)

= random effect of the k-th family nested in the genotypic group

TF

jkl

= random effect of treatment and family interaction within the genotypic group

ε

jkl

= error associated with these effects

l = treatments 1, 2, 3 and 4

i = blocks 1, 2 and 3 per treatment

j = superior and inferior genotypes

k = 10 families per genotypic group.

Data were analyzed with the MIXED procedure of the SAS 9.4® statistical program using the Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) method to determine the existence of significant differences (SAS Institute, 2015); when present, mean separation was done by direct pairwise comparison (PROC MIXED).

Results

Foliar and soil analysis

Tables 1 and 2 show that the physicochemical characteristics of the soil were adequate for the development of P. patula, although organic matter was low; the nutrients P-Bray, Cu, Mg and K were found to be deficient, according to NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 (SEMAs RNAT, 2002). Table 3 shows the results of the foliar analysis, the "technical" fertilization dose was formulated, based on the nutrient deficiencies detected.

Table 1 Physicochemical characteristics of the soil where the Pinus patula progeny trial was established in the ejido Peñuelas, Pueblo Nuevo, Chignahuapan.

| Physicochemical Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Texture | Clay |

| Bulk density | 1.19 g·cm-3 |

| Gravimetric moisture | 28.67 % t field capacity and |

| (in sieved samples) | 23.67 % at permanent wilting point |

| pH | 5.45 |

| Oranic matter | 2.45% |

Table 2 Soil nutrient concentrations of the Pinus patula progeny trial in the ejido of Peñuelas, Pueblo Nuevo, Chignahuapan.

| Nutrient | Concentration |

|---|---|

| N | 0.09% |

| Fe | 21 ppm |

| Mn | 35 ppm |

| Ca | 8.12 cmol·kg-1 |

| Zn | 0.72 ppm |

| P-Bray | 14.5 ppm |

| Cu | 0.90 ppm |

| Mg | 1.03 cmol·kg-1 |

| K | 0.26 cmol· kg-1 |

Table 3 Pinus patula foliar analysis and diagnosis based on critical concentrations reported by Sánchez-Parada et al. (2018).

| Composite sample | N | P | K | Ca | Mg | Fe | Cu | Zn | Mn | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (ppm) | |||||||||

| Inferior genotypes | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1.33 | 2 003.70 | 9 479.75 | 1 077.71 | 1 649.17 | 75.83 | 3.31 | 16.45 | 132.39 | 26.09 |

| 2 | 2.24 | 2 096.87 | 8 873.34 | 1 036.91 | 1 150.24 | 95.55 | 4.76 | 19.44 | 107.27 | 22.96 |

| 3 | 1.89 | 2 389.35 | 10 132.00 | 1 202.64 | 1 695.23 | 110.77 | 3.97 | 18.15 | 149.9 | 25.86 |

| Mean ± standard error (A) | 1.82 | 2 163.31 | 9 495.03 | 1 105.75 | 1 498.21 | 94.05 | 4.02 | 18.01 | 129.85 | 24.97 |

| (±0.27) | (±116.18) | (±363.42) | (±49.85) | (±174.49) | (±10.11) | (±0.42) | (±0.86) | (±12.37) | (±1.01) | |

| Critical concentrations (B) | 1.49 | 1 300.00 | 6 300.00 | 3 300.00 | 1 400.00 | 118.69 | 2.14 | 30.6 | 187.47 | 11.25 |

| Diagnosis (A-B) | 0.33 | 863.31 | 3 195.03 | -2 194.25 | 98.21 | -24.64 | 1.88 | -12.59 | -57.62 | 13.72 |

| Superior genotypes | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1.68 | 2 123.03 | 7 097.34 | 1 224.90 | 1 245.67 | 92.321 | 2.92 | 22.85 | 111.76 | 23.1 |

| 2 | 1.82 | 2 231.16 | 9 782.76 | 1 049.83 | 1 418.61 | 82.418 | 4.28 | 19.05 | 82.73 | 25.54 |

| 3 | 1.54 | 1 733.35 | 8 261.08 | 895.34 | 1 359.88 | 64.121 | 2.77 | 10.62 | 86.92 | 21.49 |

| Mean ± standard error (A) | 1.68 | 2 029.18 | 8 380.39 | 1 056.69 | 1 341.39 | 79.62 | 3.32 | 17.51 | 93.81 | 23.38 |

| (±0.48) | (±439.04) | (±1 912.5) | (±1 111.69) | (±414.33) | (±37.45) | (±0.70) | (±11.23) | (±52.3) | (±3.6) | |

| Critical concentrations (B) | 1.49 | 1 300.00 | 6 300.00 | 3 300.00 | 1 400.00 | 118.69 | 2.14 | 30.6 | 187.47 | 11.25 |

| Diagnosis (A-B) | 0.19 | 729.18 | 2 080.39 | -2 243.31 | -58.61 | -39.07 | 1.18 | -13.1 | -93.67 | 12.13 |

According to Tables 4 and 5, the effects of fertilization treatments were not statistically different for the variables analyzed. However, genetic condition had a significant influence on absolute and relative growth rates of biomass index production (P ≤ 0.01), as well as relative production rates of height and diameter at root collar (P ≤ 0.05). On the other hand, absolute growth rate of diameter and growth initiation were significantly different with P = 0.09.

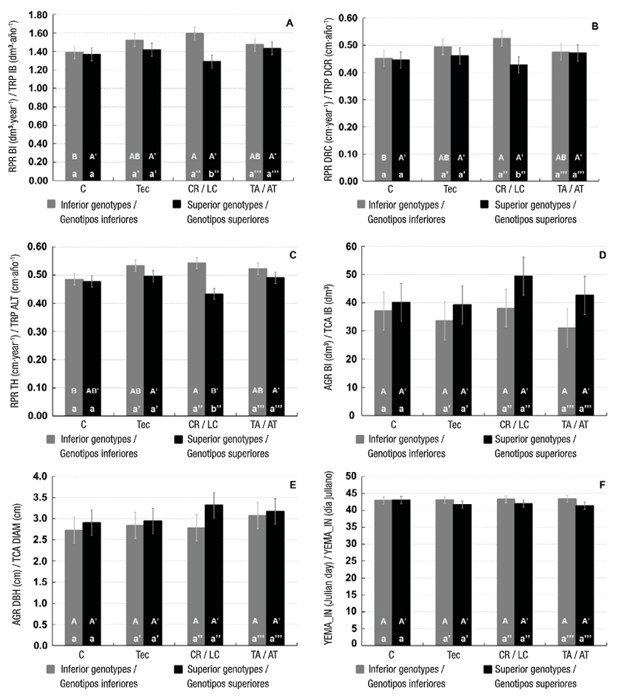

Fertilization treatments and genetic group had a significant interaction (P ≤ 0.05) on relative production rates of root collar diameter and biomass index, the same occurred with the relative rate of height production, but at a lower significance (P ≤ 0.10). For those variables, Figure 1 shows that interaction between treatment*genotypic group was statistically different (P ≤ 0.001) for the case of the superior group-controlled release fertilization treatment in contrast to the same treatment of the inferior group that generated the highest values. Control and controlled-release treatments of the inferior genetic group also caused significantly different effect (P ≤ 0.10) for the same variables (Figure 1); the controlled-release treatment generated a higher response on trees. In particular, the controlled-release treatment of the genetically superior group had a lower effect (P ≤ 0.10) on relative growth rate in total height compared to “technical” and agricultural fertilization treatments (Figure 1). The rest of the variables evaluated for the effects considered in Table 4 were not statistically different.

Table 4 Statistical significance of the evaluated effects derived from the analysis of variance in the Pinus patula progeny trial.

| Effect | RPR BI | RPR DRC | RPR TH | AGR BI | AGR DBH | YEMA_IN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pr > F | ||||||

| Fertilization (F) | 0.74 | 0.8 | 0.57 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.94 |

| Genotype group (G) | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Interaction F*G | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.92 |

AGR: absolute growth rate, RPR: relative production rate, BI: biomass index, DRC: diameter at root collar, TH: total height, DBH: diameter at breast height, YEMA_IN: initiation of growth.

Table 5 Absolute growth rate (AGR) and relative growth rate (RPR), 100 needle mass (g) and growth initiation and cessation of Pinus patula per treatment and genotypic group.

| Factor | Height (cm·year-1) | Diameter at root collar (cm·year-1) | Biomass index(dm3·year-1) | Diameter(cm·year-1) | Whorls (units·year-1) | Mass of 100 needles (g) | Yema_in (Julian days) | Yema_f (Julian days) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGR | RPR | AGR | RPR | AGR | RPR | AGR | RPR | AGR | RPR | ||||

| Treatment | |||||||||||||

| Treatment 1 | 155 ± 9.18 a | 0.48 ± 0.02 a | 3.8 ± 0.24 a | 0.45 ± 0.02 a | 38.61 ± 6.27 a | 1.38 ± 0.06 a | 2.82 ± 0.28 a | 0.72 ± 0.07 a | 4.7 ± 0.36 a | 0.48 ± 0.02 a | 2.77 ± 0.09 a | 43.0 ± 0.85 a | 312.6 ± 2.65 a |

| Treatment 2 | 154 ± 9.18 a | 0.51 ± 0.02 a | 3.9 ± 0.24 a | 0.48 ± 0.02 a | 36.45 ± 6.27 a | 1.47 ± 0.06 a | 2.90 ± 0.28 a | 0.86 ± 0.07 a | 4.2 ± 0.36 a | 0.46 ± 0.02 a | 2.87 ± 0.09 a | 42.4 ± 0.85 a | 316.9 ± 2.90 a |

| Treatment 3 | 157 ± 9.18 a | 0.49 ± 0.02 a | 4.2 ± 0.24 a | 0.48 ± 0.02 a | 43.77 ± 6.27 a | 1.44 ± 0.06 a | 3.06 ± 0.28 a | 0.71 ± 0.07 a | 4.2 ± 0.36 a | 0.46 ± 0.02 a | 2.91 ± 0.09 a | 42.6 ± 0.84 a | 308.6 ± 3.26 a |

| Treatment 4 | 157 ± 9.18 a | 0.51 ± 0.02 a | 4.0 ± 0.24 a | 0.47 ± 0.02 a | 36.83 ± 6.27 a | 1.45 ± 0.06 a | 3.12 ± 0.28 a | 0.84 ± 0.07 a | 4.4 ± 0.36 a | 0.47 ± 0.02 a | 2.80 ± 0.09 a | 42.4 ± 0.84 a | 313.0 ± 2.93 a |

| Genotype group | |||||||||||||

| Inferior | 154 ± 5.24 A | 0.52 ± 0.01 B | 3.9 ± 0.14 A | 0.49 ± 0.01 B | 34.96 ± 3.37 B | 1.49 ± 0.04 B | 2.86 ± 0.15 B | 0.80 ± 0.04 A | 4.2 ± 0.25 A | 0.47 ± 0.02 A | 2.80 ± 0.08 A | 43.2 ± 0.53 B | 312.1 ± 1.72 A |

| Superior | 158 ± 5.24 A | 0.47 ± 0.01 A | 4.1 ± 0.14 A | 0.45 ± 0.01 A | 42.86 ± 3.37 A | 1.38 ± 0.04 A | 3.09 ± 0.15 A | 0.76 ± 0.04 A | 4.6 ± 0.25 A | 0.47 ± 0.02 A | 2.87 ± 0.08 A | 42.0 ± 0.53 A | 313.4 ± 1.78 A |

Treatments: 1 = control, 2 = “technical” fertilization based on foliar analysis, 3 = controlled-release fertilization, 4 = traditional agricultural fertilization. ± standard deviation of the mean. Mean values followed by different letters are different from each other (P ≤ 0.10) by direct comparisons between pairs of means (PROC MIXED).

Figure 1 Relative production growth rates (RGR) of biomass index (BI), diameter at root collar (DRC) and total height (TH) absolute growth rates of BI and diameter (DBH), and growth initiation date (YEMA_IN) in control treatment (C), technical based on foliar analysis (Tec), controlled-release fertilizer (CR) and traditional agricultural fertilizer (TA) per genotypic group. Means with different capital letter (comparison between fertilizer treatments within each genotype) or lower-case letter (comparison between the two genotypes within each fertilizer treatment) are different from each other (P ≤ 0.10) by direct comparisons between pairs of means (PROC MIXED).

On the other hand, growth initiation was faster for superior genotypes than for inferior genotypes for one day (P ≤ 0.10) (Tables 4 and 5). Growth cessation could only be determined for 61 trees, which had an average growth period of 270 days, while 179 continued to grow, presumably due to the occurrence of the last rains in the month of November.

Table 6 shows that, at the family level within genotypic groups (F k(j) ), absolute and relative growth rates for the number of whorls had significant differences (P ≤ 0.01). This was also the case for the mass of 100 needles, but at a lower significance (P ≤ 0.10). The interaction effect between fertilization and families (TF jkl ) was significant in the case of absolute growth rate of diameter at root collar (P = 0.06) and relative production rate of number of whorls (P = 0.07).

Table 6 Statistical significances of effects evaluated at the family level, from the analysis of variance in the Pinus patula progeny trial.

| Effect | AGR VERT | RPR VERT | MASA_100 | AGR DRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pr > F | ||||

| Fertilization (F) | 0.7045 | 0.7823 | 0.6779 | 0.7099 |

| Genotype group (G) | 0.0494 | 0.9414 | 0.4504 | 0.1989 |

| F*G interaction | 0.9077 | 0.8883 | 0.445 | 0.66 |

| Family (Group) | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.0987 | 0.9403 |

| Fertilization*Family (Group) | 0.1848 | 0.0642 | 0.9969 | 0.0553 |

AGR: Absolute growth rate, RPR: Relative production rate, VERT: number of whorls, MASA_100: mass of 100 needles, DRC: diameter at root collar.

Discussion

Foliar nutrient concentrations were found within the range of normal values found by Louw and Scholes (2003) for samples taken in the growing season, except for Ca, Mn and Fe which were found in the lower limits, which is consistent with the comparison of critical concentrations reported by Sánchez-Parada et al. (2018).

Growth results were higher than those found by Gómez-Cárdenas, Vargas-Hernández, Jasso-Mata, Velázquez-Martínez, and Rodríguez-Franco (1998), who reported height growths of 108 and 66 cm in 4-year-old P. patula during two successive 300-day growing seasons in Texcoco, Mexico. However, the results were lower than those reported by Salazar-García et al. (1999) with height increments between 174 ± 43 cm and 203 ± 43 cm in one year for two provenances from Zacatlán, an area close to the present study, in 1.5-year-old unfertilized plantations of the same species. This situation also occurred in the case of the number of growth cycles (5.51 ± 1.50 and 5.77 ± 1.32) compared to those found in this experiment (AGR_VERT).

The few observed differences of the families evaluated may be related to the fact that the trial is in a relatively different water stress level site than where their parents grow; even though the collection area and the trial are 5 km apart, mean annual precipitation is 795 vs. 724 mm and the aridity index is 0.064 vs. 0.075, respectively (Virginia Tech & USDA Forest Service, 2020). The lower water availability may have influenced tree growth because height and diameter depend on water availability in the previous and current year (Kozlowski, 1964); it also affects the efficiency in the use of other resources (Binkley, Stape, & Ryan, 2004), as indicated by Vásquez-García et al. (2015), who found no differences with the application of traditional agricultural fertilizers in P. patula when light was the limiting resource.

Genetic adaptations to provenance can also limit growth, even when environmental conditions are favorable. For example, in a provenance experiment in Huauchinango, a temperate and humid site, and the provenance of Tlaxco, Tlaxcala, a cold and dry site, P. patula grew poorly (Salazar-García et al., 1999). Moreover, these authors found that elevation of provenance was negatively correlated with the number of growth cycles (r = -0.80) and the increase in height (r = -0.82); that is, the origins of higher altitude had lower growth in height and fewer cycles generated per year.

The absence of response to fertilization in this experiment contrasts with that reported by Reyes-Millalón et al. (2012), who demonstrated the efficiency of controlled-release fertilizers on growth of Pinus radiata D. Don with doses of 10 to 20 g in seedlings, 46 months after establishment. The results also contrast with the study of Vázquez-Cisneros et al. (2018), who report that some treatments with traditional agricultural fertilizers generated the same response as slow-release fertilizers in Pinus greggii Engelm. ex Parl. var. greggii, one year after applying 7 to 14 g of fertilizers during the experiment. Štofko (2010) had significant results in 3-year-old plantations of Picea abies (L.) H. Karst, applying controlled-release fertilizer (50 g), and in Larix decidua Mill. he recorded differences in height from the first year. Previous studies suggests that both fertilizer dose and plantation age may have been a limiting factor in the response to fertilization in this study.

For the present case, growth initiation date was slightly advanced by fertilization treatments, as reported by Fløistad (2002) and Pan, Jacobs, and Li (2017) in saplings of P. abies and Pinus tabuliformis Carrière, respectively, although the effect was not statistically significant. However, the genetic effect was significant, which is consistent with the fact that phenology in Pinus possesses heritable genetic control for both bud break, bud dormancy, and cold requirements for induction (temperature and photoperiod) (Cooke, Eriksson, & Junttila, 2012).

Results obtained by Salaya-Domínguez et al. (2012) and Bustillos-Aguirre et al. (2018) suggest that P. patula has low to moderate genetic control and genotype*environment (G*E) interaction at early ages. The G*E interaction can be affected by fertilization, particularly in N and P use (Li, McKeand, & Allen, 1991; Zhang, Zhou, & Yang, 2013), which occurred in this experiment as a joint response of all families within the genotypic group and not because of the existence of particularly efficient families in the use of applied nutrients. This contrasts with that reported by Zas, Pichel, Martíns, and Fernández-López (2006) in P. radiata, who reported positive effects on height with the use of traditional agricultural fertilizers and found that some families had greater efficiency in the use of nutrients; however, when analyzed as a whole, the family*fertilization interaction was not significant, apparently due to differences in fertility of each site, prior to fertilization. Martins, Sampedro, Moreira, and Zas (2009), in a similar experiment with Pinus pinaster Aiton, found significant differences for height in the five years they evaluated the plantations. These authors determined the efficiency of the use of foliar analysis to correct nutrient deficiencies in two of the three sites evaluated and demonstrated the existence of genotype interactions with nutrient availability.

Conclusions

Fertilization formulas for three-year-old Pinus patula trees, including the one proposed from the foliar analysis, showed no significant responses in growth and biomass production in the year of evaluation. However, trees show significant differences because of the effect of the genetic group and the genotype*fertilization interaction, where superior and inferior genotypes showed higher values of absolute growth and relative production rate, respectively. The controlled-release fertilizer caused the highest growth in the superior genotypes in contrast to the traditional fertilizers that were not statistically different from the control. The use of controlled-release fertilizers seems to be a viable option to promote growth of young plantations in the field, if applied in adequate doses and formulas and if adequate environmental conditions exist to optimize its use.

texto em

texto em