Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versão impressa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.14 no.78 México Jul./Ago. 2023 Epub 14-Set-2023

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v14i78.1385

Scientific article

Assessment of the effects of conservation works in forest soils of Tlaxcala, México

1Maestría en Ciencias en Sistemas del Ambiente, Centro de Investigación en Genética y Ambiente. Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala. México.

2Sitio Experimental Tlaxcala. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. México.

Soil conservation practices are widely used in Mexico to reduce soil erosion and to promote recovering of eroded soils. These practices are particularly important in the state of Tlaxcala, which has extensive areas with different levels of soil erosion. The study was carried out in 2020 in Gustavo Diaz Ordaz, Zacapexco and San Bartolomé Matlalohcan, sites with soil conservation practices (board-ditches and trench-ditches). The objective was to assess the effects of soil conservation practices through physical, chemical and biological soil properties at each location site. At the Gustavo Díaz Ordaz site, the values of soil properties did not significantly different from the control with the conservation practices after eight years of its establishment. At Zacapexco, after five years of the establishment of board-ditches, there is a positive impact on several chemical and biological soil properties, whereas, at San Bartolomé Matlalohcan, after more than 40 years of establishment of board-ditches, there were no significant effects on biological properties of the soil. A principal components analysis allowed us to identify that organic matter content (OM), cation exchange capacity (CEC), calcium, pH, total N and the proportion of clay and sand, are properties that significantly influence soil quality in the study sites, therefore, monitoring these variables is greatly useful in assessing the impact of conservation practices.

Key words Soil quality; soil degradation; conservation practices; edaphic properties; board-ditch; trench-ditch

Las obras de conservación de suelos son muy utilizadas en México para disminuir la erosión y propiciar la recuperación de suelos erosionados. Estas obras son particularmente notables en Tlaxcala, estado que presenta grandes superficies con diferentes niveles de erosión edáfica. El estudio se llevó a cabo en 2020 en las localidades Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, Zacapexco y San Bartolomé Matlalohcan, Tlaxcala; sitios con obras de conservación de suelo (zanja bordo y zanja trinchera). El objetivo fue evaluar el impacto del establecimiento de las obras de conservación a través de propiedades físicas, químicas y biológicas del suelo. En el sitio Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, los valores de las propiedades del suelo no fueron significativamente diferentes respecto al testigo a ocho años de su implementación. En Zacapexco, a cinco años de la construcción de las zanjas bordo, se verificó un impacto positivo en varias propiedades químicas y biológicas del suelo. En San Bartolomé Matlalohcan, después de más de 40 años de la realización de las zanjas bordo, no se observaron cambios significativos en las propiedades biológicas del suelo. El análisis de componentes principales permitió identificar que la materia orgánica (MO), la capacidad de intercambio catiónico (CIC), calcio, pH, N total y la proporción de arcilla y arena son propiedades que influyen de manera importante en la calidad del suelo en los sitios de estudio, por lo que el monitoreo de estas variables es de gran utilidad en la evaluación del impacto de obras de conservación.

Palabras clave Calidad del suelo; degradación del suelo; prácticas de conservación; propiedades edáficas; zanja bordo; zanja trinchera

Introduction

In Mexico, socioeconomic factors and human activities (agriculture, livestock and deforestation) influence soil degradation by promoting wind and water erosion (Cotler et al., 2022), particularly in rural areas (Espinosa et al., 2011; Li and Fang, 2016), as is the case of the state of Tlaxcala, which presents this problem in 76.8 % of its territory (Semarnat and Colpos, 2002).

Due to this problematic situation, the construction of soil conservation works has been highly recommended to speed up the rehabilitation process, since they seek to improve and recover quality and minimize the process of soil erosion. Within the soil conservation works, in Mexico the trench stands out, which is implemented indistinctly in different geographical and ecological conditions (Cotler et al., 2015), however, it has been argued that its construction can affect the conditions of water infiltration, increase the erosion process and decrease the organic carbon (OC) content in the soil, which affects biological activity (Cotler et al., 2022).

In contrast, other studies have recorded positive results with some conservation works. For example, González-Romero et al. (2018) analyzed the functionality and the effect on the soil over time through physical, chemical and biological properties, after establishing silt control dams; the same authors describe that the works positively influenced the decrease in bulk density (Bd) and pH, increases in the OM concentration and the activity of the dehydrogenase enzyme (DHS).

On the other hand, in stone-based terraces as a conservation work, soil conditions were improved compared to sites without work, which provides positive effects on soil fertility and plant production (Welemariam et al., 2018). Reyes et al. (2019) recorded that the board ditches favor the capture of water and with it the establishment of plant species. Grasses and other herbaceous plants establish more quickly in areas with conservation works, due to the increase in soil moisture (Doria et al., 2022). Muscolo et al. (2014) point out that soil properties are sensitive to variations in climate and management; thus, their evaluation will allow identifying the impacts of degradation.

Therefore, under the different edaphic conditions of the sites and the intervention through conservation works and the establishment of vegetation, a positive change in the edaphic variables is possible. Therefore, the objective of this work was to evaluate the physical, chemical and biological properties of the soil with and without the presence of conservation works and to determine possible effects and relationships between said properties in each study area.

Materials and Methods

Study sites

Site 1. Ejido Gustavo Díaz Ordaz (GDO). Is located in the Emiliano Zapata municipality (19°32'31.6'' N and 98°08'58.0'' W) at 2 415 masl, with a total area of 470 ha. Subhumid temperate climate, 6.5-22.1 °C temperature, 6.8-140.8 mm rainfall, and predominant soil order Leptosol (30.11 %) (INEGI, 2010a). The dominant vegetation is pine-oak forest (Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl., P. greggii Engelm. ex Parl., Quercus laurina Bonpl. and Q. rugosa Née) (Conafor, 2012) and among the conservation works there is a notable presence of pastures.

In 2012, different conservation works were established in the Peña del Chivo area, whose soils show moderate degradation, due to deforestation and water erosion; in 30 ha, trench ditches and board ditches were built alternately, with a 40 ° slope (Conafor, 2012). The specific study area was 2.5 ha, including conservation works and the control (without conservation works).

Site 2. Zacapexco (ZAC). Private property within the San Pedro Ecatepec community, Atlangatepec municipality (19°32'31.6'' N and 98°08'58.0'' W) with an altitudinal interval between 2 480 and 2 600 m. Subhumid temperate climate with summer rains, 12-14 °C temperature, 600-700 mm rainfall, and Phaeozem soil order (54 %) (INEGI, 2010b).

In 2015, 40 ha of trenches and 50 ha of individual terraces were built. There are slopes of 15 to 20 % at the place and soil degradation was caused, mainly, by overgrazing and laminar water erosion (Conafor, 2015). The predominant vegetation is Juniperus deppeana Steud. Forests and where the conservation works were established, seedlings of Pinus pseudostrobus were planted.

Site 3. San Bartolomé Matlalohcan (SBM). Community located in the Tetla de La Solidaridad municipality (19°28'11.68" N and 98°07'16.65" W) at an average elevation of 2 516 masl. Subhumid temperate climate with rains in summer, 12-14 °C temperature, 600-900 mm rainfall, and soil order Phaeozem (61.8 %), with a slope of 15-20 % (INEGI, 2010c).

In this site, board-ditch and terraces were built in 7 ha between 1976 and 1978, as experimental plots of the National Institute of Forest, Agriculture and Livestock Research (INIFAP) to seek the rehabilitation of the tepetate (porous rocky soil). During sampling, the presence of introduced species such as eucalyptus (Eucalyptus L'Hér. spp.) and casuarina (Casuarina equisetifolia L.) was observed.

Soil sampling and sample preparation

At the GDO site, a grid with quadrats of 158 m×158 m was drawn on 2.5 ha of land, using the Schweizer´s systematic soil sampling method (2011). Two plots with a trench ditch (18 samples) and two with a board ditch (18 samples) were selected, in addition to six samples in a plot as a control (without conservation work). Within each quadrat, soil samples were collected between ditches at a depth of 0-30 cm. In ZAC, 3 ha were sampled with a trench (9 samples) and 1 ha as a control (without conservation work, 5 samples). For SBM, the sampling was in 1.5 ha with a ditch along the edge (9 samples) and in 0.5 ha without conservation work considered a witness (9 samples).

For the microbiological analysis of the soil, 100 g of each of the soil samples were taken and transferred to the Natural Resources Laboratory of the Genetics and Environment Research Center-UATx, cold, inside a Coleman® cooler with gel bags 250g POWERICE® coolant. Composite samples were made for each site using the quartering method, based on NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 (Semarnat, 2002). For GDO, 14 composite samples were obtained, in ZAC 7 and SBM 6, later stored at 4 °C in an Imbera® refrigerator to inhibit microbial activity. The rest of the soil from each sample was placed on Kraft paper to dry at room temperature and in the shade. The soil was sieved in a 2 mm mesh, all of the above following NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 (Semarnat, 2002).

Soil analysis

Each soil sample was determined texture, Bd (bulk density), EC (electrical conductivity); OM (organic matter); OC (organic carbon); CEC (cation exchange capacity), pH, total N, phosphorus, potassium, calcium and magnesium by methods established in NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 (Semarnat, 2002). Microbial respiration through the quantification of CO2, the activity of the dehydrogenase enzyme and the bacterial biomass by the methods described by García et al. (2003).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed by site using one-way analysis of variance and a Tukey mean comparison test (p=0.05). Previously, the data were analyzed to verify compliance with the assumptions of normality (Kolmogorov) and homogeneity of variance (Levene). The model used for the analysis was the one described in Equation 1 (InfoStat, 2008).

Where:

µ = General average

τi = Effect of the i -th treatment

εij = Experimental error

From the soil properties of the three sites with and without conservation works, a Pearson correlation analysis (p=0.05) and a principal component analysis (PCA) were carried out to determine their contribution to the total variation of the data. All of the above was done with the statistical software InfoStat free version 2020 (Balzarini et al., 2008).

Results and Discussion

Gustavo Díaz Ordaz

The soils between the board-ditch and trench-ditch treatments show significant differences (p<0.05) in bacterial biomass and total N with respect to the control. Based on the values observed in these two variables, it is clear that the soil conservation works and the vegetation present did not increase the values, since they are lower than the control (Table 1). The above agrees with Cotler et al. (2013), who report that the construction of trench-ditches did not allow an increase in the total N content, even with vegetation; they state that the mineralization of the litter to inorganic forms (ammonium and nitrates) will depend on the amount that can be converted by the microbial biomass, which in this case, was also lower with the conservation works, which suggests low effectiveness of the trench-ditch. Beltrán et al. (2018) point out that the establishment of plant species allows a greater diversity of microorganisms and microbial activity, in such a way that trophic relationships are established that contribute to the improvement of soil quality.

Table 1 Analysis of variance of physical, chemical and biological parameters of the soil with and without conservation work in GDO.

| Parameter | P Value | Board-ditch | Trench-ditch | Control | Reference† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand (%) | 0.1955 | 71.9±1.0 a | 73.1±1.07 a | 75.76±1.8 a | Sandy loam |

| Clay (%) | 0.1846 | 5.94±0.62 a | 6.61±0.64 a | 4.28±1.07 a | |

| Silt (%) | 0.3362 | 22.1±0.96 a | 20.28±0.9 a | 19.96±1.6 a | |

| Bd (g cm-3) | 0.4839 | 0.94±0.02 a | 0.92±0.02 a | 0.91±0.02 a | <1 |

| pH | 0.4926 | 6.27±0.11 a | 6.09±0.12 a | 6.06±0.20 a | 5.1-6.5 |

| EC (dS m-1) | 0.8187 | 0.06±0.0024 a | 0.06±0.0042 a | 0.06±0.002 a | <1 |

| OM (%) | 0.6423 | 5.10±0.42 a | 4.53±0.44 a | 4.87±0.80 a | 4.1-6.0 |

| OC (%) | 0.6423 | 2.96±0.25 a | 2.62±0.25 a | 2.82±0.47 a | 1.2-2.9 2.9-4.6 |

| CEC [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.5700 | 45±4.01 a | 38.9±4.12 a | 43.2±6.94 a | >40 25-40 |

| Total N (%) | ≤0.0001 | 0.16±0.01 b | 0.12±0.01 c | 0.39±0.01 a | <0.30 |

| P (mg kg-1) | 0.8333 | 8.37±1.15 a | 9.15±1.15 a | 10.69±1.63 a | <15 |

| Ca [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.0526 | 7.55±0.04 a | 5.6±0.04 a | 6±0.05 a | 5-10 |

| Mg [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.1250 | 2.4±0.14 a | 1.8±0.14 a | 2±0.2 a | 1.3-3.0 |

| K [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.6250 | 0.40±0.04 a | 0.45±0.04 a | 0.4±0.05 a | 0.3-0.6 |

| Microbial respiration (mg C-CO2 kg-1 soil) | 0.3725 | 23.35±1.34 a | 21.39±1.38 a | 23.93±2.33 a | ----- |

| Dehydrogenase enzyme (µg TTC g-1 soil) | 0.7954 | 0.51±0.09 a | 0.47±0.09 a | 0.42±0.11 a | ----- |

| Bacterial biomass (UFC×10³ g-1 soil) | 0.0021 | 1 142±108.28 b | 845±98.85 b | 1 820±171.21 a | ----- |

*Equal letters per row indicate no significant differences (p≥0.05); Tukey´s Mean±E.E; †NOM-021-RECNAT-2000; Bd = Bulk density; EC = Electric conductivity; OM = Organic matter; OC = Organic carbon; CEC = Cation exchange capacity.

The establishment of trenches coupled with the vegetation did not modify the physical properties of the soil for eight years, the sand fraction predominates by 73 % on average and the bulk density without variation. On the other hand, even without significant differences, the chemical properties show that the presence of trees tends to increase the acidity of the soil (Khalaji et al., 2021). With the trenches on board, an increase in the content of OM, OC, Ca, Mg and CEC was observed, which is high [>40 Cmol (+) kg-1] based on NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 (Table 1). Vazquez-Alvarado et al. (2011) refer that soil conservation works and an adequate selection of plant species are important to obtain positive results, due to the fact that there is an increase in the OM content and, therefore, a greater retention of moisture and soil particles, as well as a greater number of microorganisms (Doria et al., 2022). However, this was not observed in this site for bacterial biomass, which was significantly higher in the control soil.

Zacapexco

In the soil between the board-ditches, the sand and clay fraction, the pH, OM, OC, microbial respiration and the dehydrogenase enzyme presented significant differences (p<0.05) with respect to the control soil (Table 2). At this site, the construction of the board-ditches probably allowed an increase in soil moisture, which favors the presence of herbaceous plants and grasses associated with J. deppeana and P. pseudostrubos, which improves the chemical and biological properties of the soil.

Table 2 Analysis of variance of the physical, chemical and biological properties of the soil with and without conservation work in ZAC.

| Property | P value | Board-ditch | Control | Reference† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand (%) | 0.0118 | 78.86±2.07 a | 68.58±2.78 b | Sandy loam |

| Clay (%) | 0.0205 | 7.67±2.44 a | 15.77±1.82 b | |

| Silt (%) | 0.2185 | 13.47±1 a | 15.65±1.35 a | |

| Bd (g cm-3) | 0.0907 | 0.96±0.02 a | 1.03±0.03 a | <1 |

| pH | 0.0319 | 7.55±0.16 b | 8.24±0.12 a | 7.4-8.5 |

| EC (dS m-1) | 0.6218 | 0.04±0.01 a | 0.04±0.01 a | <1 |

| OM (%) | 0.0031 | 3.94±0.38 a | 1.61±0.5 b | <4.0 |

| OC (%) | 0.0031 | 2.28±0.22 a | 0.9±0.29 b | <1.2 1.2-2.9 |

| CEC [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.1566 | 30.58±1.24 a | 27.45±1.66 a | 25-40 |

| N total (%) | 0.1613 | 0.23±0.04 a | 0.27±0.05 a | <0.30 |

| P (mg kg-1) | 0.1000 | 0.3±0 a | 0.4±0 a | 0.3-0.6 |

| Ca [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.3815 | 8.8±1.98 a | 5.6±2.42 a | 5-10 |

| Mg [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.4086 | 2.8±0.66 a | 1.8±0.81 a | 1.3-3 |

| K [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.1000 | 0.3±0 a | 0.4±0 a | 0.3-0.6 |

| Microbial respiration (mg C-CO2 kg-1 soil) | 0.0045 | 23.77±1.46 a | 15.29±1.95 b | ----- |

| Dehydrogenase enzyme (µg TTC g-1 soil) | 0.0025 | 2.41±0.11 a | 0.05±0.12 b | ----- |

| Bacterial biomass (UFC×10³ g-1 soil) | 0.7245 | 1 047.78±133.65 a | 971.67±163.69 a | ----- |

*Equal letters per row indicate no significant differences (p≥0.05); Tukey´s Mean±E.E. †NOM-021-RECNAT-2000; Bd = Bulk density; EC = Electric conductivity; OM = Organic matter; OC = Organic carbon; CEC = Cation exchange capacity.

Five years after the establishment of the conservation works, there is a decrease in pH, an increase in OM and OC, in CEC, phosphorus, calcium and magnesium, as well as a notable improvement in biological activity. This highlights the importance of maintaining and incorporating plant cover with the correct species together with conservation works, since plants supply OC as an energy source for soil organisms to carry out their metabolic activity, which will depend on the type of soil, time of year, climate, nutriments, topographic conditions of the site and the type of vegetation (Yáñez et al., 2017; Khalaji et al., 2021; Doria et al., 2022).

San Bartolomé Matlalohcan

The average values of Bd, EC, CEC, the content of Ca, Mg and K were significantly different (p<0.05) between the treatments (Table 3). On the other hand, the values of the content of OM, OC and of the biological properties, although without significant differences, reflect a slight increase. At this site, conservation works were complemented by reforestation with eucalyptus trees. It has been indicated that although eucalyptus trees are fast growing, they have an allelopathic effect that negatively impacts the soil (Murillo et al., 2005), because they modify their characteristics and decrease the biodiversity of fungi, lichens, and herbaceous plants. In the same way, the functioning of the ecosystem is altered in processes such as the decomposition of litter, due to the decrease in soil microorganisms (Munguía et al., 2004; García-Osorio et al., 2020; Solís-Vargas et al., 2021), what is observed in this particular site.

Table 3 Analysis of variance of the physical, chemical and biological properties of the soil with and without conservation work in SBM.

| Property | P value | Board-ditch | Control | Reference† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand (%) | 0.1886 | 77.71±1.87 a | 81.62±2.12 a | Sandy loam |

| Clay (%) | 0.0559 | 8.38±1.18 a | 4.66±1.34 a | |

| Silt (%) | 0.9417 | 13.91±1.66 a | 13.72±1.88 a | |

| Bd (g cm-3) | 0.0004 | 0.91±0.02 b | 1.03±0.02 a | <1 |

| pH | 0.6790 | 5.68±0.18 a | 5.79±0.18 a | 5.1-6.5 |

| EC (dS m-1) | 0.0051 | 0.03±0.0028 a | 0.01±0.0028 b | <1 |

| OM (%) | 0.4433 | 1.62±0.24 a | 1.14±0.24 a | <4.0 |

| OC (%) | 0.4433 | 0.94±0.14 a | 0.66±0.14 a | <1.2 |

| CEC [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.0086 | 26.00±1.51 a | 11.25±1.85 b | 5-15 25-40 |

| N total (%) | 0.2629 | 0.1±0.3 a | 0.15±0.3 a | <0.30 |

| P (mg kg-1) | 0.8580 | 7.41±0.3 a | 7.33±0.3 a | <15 |

| Ca [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.0032 | 8.93±0.6 a | 3.6±0.6 b | 2-5 5-10 |

| Mg [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.0008 | 3.07±0.13 a | 1.33±0.13 b | 1.3-3.0 >3 |

| K [Cmol(+) kg-1] | 0.0003 | 0.67±0.03 a | 0.13±0.03 b | <0.2 >0.6 |

| Microbial respiration (mg C-CO2 kg-1 soil) | 0.3459 | 17.66±1.51 a | 15.18±1.51 a | ----- |

| Dehydrogenase enzyme (µg TTC g-1 soil) | 0.6704 | 0.09±0.05 a | 0.03±0.07 a | ----- |

| Bacterial biomass (UFC×10³ g-1 soil) | 0.5776 | 350±26.26 a | 328.89±26.26 a | ----- |

*Equal letters per row indicate no significant differences (p≥0.05); Tukey´s Mean±E.E; †NOM-021-RECNAT-2000; Bd = Bulk density; EC = Electric conductivity; OM = Organic matter; OC = Organic carbon; CEC = Cation exchange capacity.

Leaf litter is the most important source of nutrients. Particularly, the decomposition of eucalyptus leaves releases a greater amount of K (0.96 %) than P (0.06 %) and N (0.89 %), which depends on soil conditions (Munguía et al., 2004). The cation exchange capacity was verified, mainly, by the clay content, which was higher with the presence of the board-ditch, since the organic matter is low, from the slow decomposition of the litter (Welemariam et al., 2018; García-Osorio et al., 2020).

Relationship between soil properties

In this part of the results, bulk density (Bd) is negatively correlated with OM, potassium, calcium and microbial respiration, which means that if Bd decreases, there will be less compaction; this will increase the pore space and, consequently, there will be an increase in the water storage capacity, which, in turn, will impact the functions of soil microorganisms (Notaro et al., 2018; Rosero et al., 2019; Barajas et al., 2020). Cotler (2015) evaluated the construction of trench-ditches and reported that Bd increased, and explained that this material which is deposited undergoes an alteration that is reflected in OM and microbial activity, as observed in GDO.

The OM content is a measure of soil quality since it is considered a source of energy and a reserve of nutriments, contributes to the resilience of the soil-plant system, favors CEC, improves the availability of phosphorus, influences the increase in water retention capacity and attenuates thermal variations in the soil, in addition to microbial diversity and activity (Fischer and Dubis, 2019; Frugoni et al., 2020). This situation was reflected in GDO and ZAC with the establishment of the board-ditch and the vegetation, and there was an improvement in the chemical and biological properties of the soil. On the other hand, OM also had a positive influence on EC, P, K and Ca. Total N with bacterial biomass and CEC, which was higher in the three sites, is positively associated with Mg, but negatively with K and Ca (Table 4).

Table 4 Pearson correlation of soil properties with and without conservation work in three sites in Tlaxcala.

| Sand | Clay | Silt | Bd | pH | EC | OM | OC | N | P | CEC | Mg | K | Ca | RM | BB | DHS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Clay | -0.80* | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Silt | -0.4 | -0.21 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| Bd | -0.35 | 0.75 | -0.63 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| pH | -0.64 | 0.85* | -0.24 | 0.63 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| EC | -0.42 | -0.11 | 0.89* | -0.66 | 0.01 | 1 | |||||||||||

| OM | 0.13 | -0.57 | 0.68 | -0.89* | -0.27 | 0.83* | 1 | ||||||||||

| OC | 0.12 | -0.57 | 0.69 | -0.89* | -0.27 | 0.83* | 1.00* | 1 | |||||||||

| N | -0.51 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1 | ||||||||

| P | -0.4 | 0.04 | 0.69 | -0.62 | 0.05 | 0.82* | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.37 | 1 | |||||||

| CEC | -0.1 | 0.61 | -0.76* | 0.63 | 0.64 | -0.55 | -0.56 | -0.56 | 0.17 | -0.2 | 1 | ||||||

| Mg | 0.09 | 0.38 | -0.7 | 0.47 | 0.2 | -0.65 | -0.61 | -0.62 | -0.13 | -0.21 | 0.86* | 1 | |||||

| K | -0.16 | -0.45 | 0.95* | -0.78* | -0.4 | 0.89* | 0.83* | 0.83* | -0.01 | 0.62 | -0.85* | -0.78* | 1 | ||||

| Ca | -0.14 | -0.47 | 0.95* | -0.8* | -0.38 | 0.87* | 0.84* | 0.85* | 0.08 | 0.63 | -0.82* | -0.76* | 0.99* | 1 | |||

| RM | 0.42 | -0.58 | 0.26 | -0.84* | -0.32 | 0.46 | 0.79* | 0.79* | -0.1 | 0.6 | -0.12 | -0.06 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 1 | ||

| BB | -0.34 | 0 | 0.67 | -0.43 | 0.19 | 0.69 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.78* | 0.7 | -0.36 | -0.56 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.33 | 1 | |

| DHS | 0.28 | -0.1 | -0.28 | -0.21 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.1 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.07 | -0.12 | -0.1 | 0.62 | 0.15 | 1 |

Bd = Bulk density (g cm-3); EC = Electric conductivity (dS m-1); OM = Organic matter (%); OC = Organic carbon (%); N = Total Nitrogen (%); P = Phosphorous (mg kg-1), CEC = Cation exchange capacity [Cmol(+) kg-1)]; Mg = Magnesium [(Cmol(+) kg-1]; K= Potasium [Cmol(+) kg-1]; Ca = Calcium [Cmol (+) kg-1]; RM = mg CO2 kg-1 soil; BB = UFC×103, DHS = Dehydrogenase enzyme (µg TPF g-1). *Significant values (p<0.05).

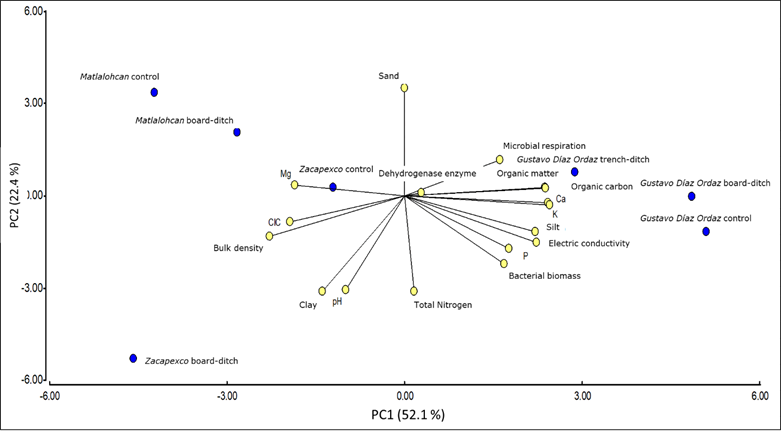

The principal component analysis (PCA) (Figure 1) showed that 74.5 % of the total variability of the data is explained by the PC1 (52.1 %) and PC2 (22.4 %) components. The variables with the greatest weight in CP1 were cation exchange capacity (0.32), calcium (0.32), organic carbon (0.32) and organic matter (0.31), which presented significant correlations (Table 4) and influence the biological activity of the soil. Similar results were reported by Rosero et al. (2019), who through a PCA recognized that in forest, grassland and silvopastoral system soils, PC1 explains that 48.48 % of the variability is determined by CEC (0.97) and calcium (0.86), while, in PC2 (21.69 %), the sand and clay particles, the pH and total N stood out.

On the other hand, in forest soils with native vegetation, Notaro et al. (2018) obtained values in PC1 of 79.01 % for variables such as enzymatic activity, carbon of microbial biomass and soil OC, which is directly related to OM and humification processes.

In addition, the PC2 was explained by the sand particle (0.47), clay (-0.41), pH (-0.41) and total N (-0.41), being associated with the Bd and OM values. Alvarez-Arteaga et al. (2020) recorded 10.36 % variability associated with the mineral fraction of the soil, true density, silt, sand, and CEC. This suggests that the correlations and importance of the soil variables can be modified depending on the specific conditions of each locality. In the soils of the sites under study there is a predominance of the sand fraction, which implies a greater infiltration and, with it, a decrease in the water retention capacity that impacts the absorption by the roots of the plants and, therefore, in the dynamics of organic matter and biological activity of the soil (Díaz et al., 2018).

Garcia-Osorio et al. (2020) mention that as the age of a reforestation increases, there will be a gradual integral recovery of the ecosystem, due to the fact that the OM incorporation process increases until reaching amounts similar to the original site. This assertion is only partially reflected in this study, since in SBM, at 40 years, there is a notable difference in terms of soil quality with respect to GDO and ZAC. Clearly, in SBM the established tree species plays a relevant role in the lack of recovery of soil properties, unlike ZAC where there are native species with conservation works.

With the results obtained, the relevance of evaluating the impact of establishing soil conservation works through soil properties is confirmed, since they provide more detailed information for planning and management of works and soil conservation or recovery practices.

Conclusions

The bordo ditch is the conservation work that, together with the native vegetation, shows an improvement in the quality of the soil in Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and Zacapexco, but not in San Bartolomé Matlalohcan, where after more than 40 years, the type of vegetation established in the rehabilitation works have not had a positive impact on the biological quality of the soil.

The analysis of principal components allowed us to identify that organic matter, cation exchange capacity, calcium, pH, total N and the proportion of clay and sand are properties that significantly influence soil quality, so monitoring of these variables are useful in evaluating the impact of establishing soil conservation works.

Acknowledgements

The support of Eng. J. Nicolás G. and S. Zamora V. is greatly appreciated, as well as the owners of the private properties, who provided basic information on the conservation works and allowed access to the sites in order to develop this study.

REFERENCES

Álvarez-Arteaga, G., A. Ibáñez-Huerta, M. E. Orozco-Hernández y B. García-Fajardo. 2020. Regionalización de indicadores de calidad para suelos degradados por actividades agrícolas y pecuarias en el altiplano central de México. Quivera Revista de Estudios Territoriales 22(2):5-19. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=40165706001 . (12 de enero 2021). [ Links ]

Barajas G., G., D. Hernández R., S. Paredes G., J. C. Peña B. y J. Álvarez S. 2020. CO2 microbiano edáfico en un bosque de Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. & Cham. en la Ciudad de México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 11(57):108-131. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v11i57.552. [ Links ]

Beltrán L., S., C. A. García D., C. Loredo O., J. Urrutia M., J. A. Hernández A. y H. G. Gámez V. 2018. “Llorón Imperial”, Eragrostis curvula (Schrad) Nees, variedad de pasto para zonas áridas y semiáridas. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Pecuarias 9(2):400-407. Doi: 10.22319/rmcp.v9i2.4532. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor) . 2012. Anexo técnico: Ejido Gustavo Díaz Ordaz. Gerencia estatal Tlaxcala: Conafor. Tlaxcala, Tlax., México. 15 p. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor). 2015. Anexo técnico: Rancho Zacapexco. Gerencia estatal Tlaxcala: Conafor. Tlaxcala, Tlax., México. 18 p. [ Links ]

Cotler, H., J. A. Lara, S. Cram, A. Guevara, … and J. M. Núñez. 2022. Assessment of unintended effects of ditches on ecosystem services provided by Iztaccihuatl-Popocatépetl National Park, Mexico. Acta Universitaria 32:1-24. Doi: 10.15174/au.2022.3647. [ Links ]

Cotler, H., S. Cram, S. Martínez T. y V. Bunge. 2015. Evaluación de prácticas de conservación de suelos forestales en México: caso de las zanjas trinchera. Investigaciones Geográficas (88):6-18. Doi: 10.14350/rig.47378. [ Links ]

Cotler, H., S. Cram, S. Martínez-Trinidad and E. Quintanar. 2013. Forest soil conservation in central Mexico: An interdisciplinary assessment. Catena 104:280-287. Doi: 10.1016/j.catena.2012.12.005. [ Links ]

Díaz M., C., C. Herrera A. y K. Prada S. 2018. Características fisicoquímicas de suelos con relación a su conformación estructural. Investigación e Innovación en Ingenierías 6(1):58-69. Doi: 10.17081/invinno.6.1.2775. [ Links ]

Doria T., O. A., D. O. Mendoza A., M. Gutiérrez G. y M. Pando M. 2022. Efecto de una obra de conservación de suelo en el patrón de distribución de la vegetación y funcionalidad del ecosistema. E-CUCBA 9(17):229-237. Doi: 10.32870/ecucba.vi17.230. [ Links ]

Espinosa R., M., E. Andrade L., P. Rivera O. y A. Romero D. 2011. Degradación de suelos por actividades antrópicas en el norte de Tamaulipas, México. Papeles de Geografía (53-54):77-88. https://revistas.um.es/geografia/article/view/143451/128731 . (13 de marzo de 2023). [ Links ]

Fischer, Z. and L. Dubis. 2019. Soil respiration in the profiles of forest soils in Inland Dunes. Open Journal of Soil Science 9:75-90. Doi: 10.4236/ojss.2019.95005. [ Links ]

Frugoni, M. C., G. Falbo y M. González M. 2020. Los suelos derivados de cenizas volcánicas en la provincia del Neuquén, Argentina. In: Imbellone, P. A. y O. A. Barbosa (Edits.). Suelos y vulcanismo. Asociación Argentina de la Ciencia del Suelo (AACS). Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, BA, Argentina. pp. 307-332. http://www.suelos.org.ar/sitio/nuevo-libro-suelos-y-vulcanismo-argentina/ . (25 de marzo de 2021). [ Links ]

García, C., F. Gil, T. Hernández y C. Trasar (Edits.). 2003. Técnicas de análisis de parámetros bioquímicos en suelos: medida de actividades enzimáticas y biomasa microbiana. Ediciones Mundi-Prensa. Madrid, MD, España. 371 p. [ Links ]

García-Osorio, M. T., F. O. Plascencia-Escalante, G. Ángeles-Pérez, F. Montoya-Reyes y L. Beltrán-Rodríguez. 2020. Producción y tasa de descomposición de hojarasca en áreas bajo rehabilitación en El Porvenir, Hidalgo, México. Madera y Bosques 26(3):e2632099. Doi: 10.21829/myb.2020.2632099. [ Links ]

González-Romero, J., M. E. Lucas-Borja, P. A. Plaza-Álvarez, J. Sagra, D. Moya and J. De Las Heras. 2018. Temporal effects of post-fire check dam construction on soil functionality in SE Spain. Science of the Total Environment 642:117-124. Doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.052. [ Links ]

InfoStat. 2008. Infostat. Software Estadístico. Manual del usuario. Versión 2008. Editorial Brujas. Córdoba, Cba, Argentina, 334 p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283491340_Infostat_manual_del_usuario . (10 de septiembre de 2021). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2010a. Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010 Terrenate, Tlaxcala. Clave geoestadística 29030. INEGI. Aguascalientes, Ags., México. 10p. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/29/29030.pdf . (10 de junio de 2020). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2010b. Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010. Atlangatepec, Tlaxcala. Clave geoestadística 29003. INEGI. Aguascalientes, Ags., México. 10p. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/29/29003.pdf . (10 de junio de 2020). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2010c. Compendio de información geográfica municipal 2010. Tetla de la Solidaridad, Tlaxcala. Clave geoestadística 29031. INEGI. Aguascalientes, Ags., México. 10p. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/29/29031.pdf . (10 de junio de 2020). [ Links ]

Khalaji, J., N. Gharahi and M. Pajouhesh. 2021. Investigating the effect of different water and soil conservation practices on some soil properties. Environment and Water Engineering 7(1):143-156. Doi: 10.22034/jewe.2020.248329.1425. [ Links ]

Li, Z. and H. Fang. 2016. Impacts of climate change on water erosion: A review. Earth-Science Reviews 163:94-117. Doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.10.004. [ Links ]

Munguía, R., J. Beer, J-M. Harmand y J. Haggar. 2004. Tasas de descomposición y liberación de nutrientes de la hojarasca de Eucalyptus deglupta, Coffea arabica y hojas verdes de Erythrina poeppigiana, solas y en mezclas. Agroforestería en las Américas 41-42:62-68. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236649951_Tasas_de_descomposicion_y_liberacion_de_nutrientes_de_la_hojarasca_de_Eucalyptus_deglupta_Coffea_arabica_y_hojas_verdes_de_Erythrina_poeppigiana_solas_y_en_mezclas_Decomposition_and_nutrient_release_r . (20 de agosto de 2020). [ Links ]

Murillo, W., W. Quiñones y F. Echeverri. 2005. Evaluación del efecto alelopático de tres especies de Eucalyptus. Actualidades Biológicas 27:105-108. Doi: 10.17533/udea.acbi.331568. [ Links ]

Muscolo, A., M. R. Panuccio, C. Mallamaci and M. Sidari. 2014. Biological indicators to assess short-term soil quality changes in forest ecosystems. Ecological Indicators 45:416-423. https://www.academia.edu/19596605/Biological_indicators_to_assess_short_term_soil_quality_changes_in_forest_ecosystems . (11 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Notaro, K. A., E. V. de Medeiros, G. P. Duda, K. A. Moreira, … and W. da S. Moraes. 2018. Enzymatic activity, microbial biomass, and organic carbon of Entisols from Brazilian tropical dry forest and annual and perennial crops. Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research 78(1):68-77. Doi: 10.4067/S0718-58392018000100068. [ Links ]

Reyes C., A., M. R. Martínez M., E. Rubio G., E. García M. y A. A. Exebio G. 2019. Impacto del sistema zanja bordo sobre la cobertura vegetal en pastizales de la región Mixteca, estado de Oaxaca. Terra Latinoamericana 37(3):231-242. Doi: 10.28940/terra.v37i3.327. [ Links ]

Rosero, J., J. Vélez, H. Burbano y H. Ordóñez. 2019. Cuantificación de la respiración y biomasa microbiana en Andisoles del sur de Colombia. Agro Sur 47(3):15-25. Doi: 10.4206/agrosur.2019.v47n3-03. [ Links ]

Schweizer L., S. 2011. Muestreo y análisis de suelos para diagnóstico de fertilidad. Instituto Nacional de innovación y transferencia en tecnología agropecuaria y Ministerio de Agricultura y Ganadería. San José, SJ, Costa Rica. 18 p. https://www.mag.go.cr/bibliotecavirtual/P33-9965.pdf . (20 de enero de 2020). [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat) y Colegio de Postgraduados (Colpos). 2002. Evaluación de la degradación del suelo causada por el hombre en la República Mexicana, escala 1:250 000. Memoria Nacional 2001-2002. Colpos Campus Montecillo. Texcoco, Edo. Méx., México. 69 p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307967321 . (11 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2002. Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-021-RECNAT-2000, Que establece las especificaciones de fertilidad, salinidad y clasificación de suelos. Estudios, muestreo y análisis. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 31 de diciembre de 2002. México, D. F., México. 73 p. http://www.ordenjuridico.gob.mx/Documentos/Federal/wo69255.pdf . (20 de febrero de 2020). [ Links ]

Solís-Vargas, A., V. Martínez-Albán y R. Camacho-Herrera. 2021. Potencial de captura de carbono en plantaciones mixtas con Araucaria hunsteinii K. Schum. en la Zona Atlántica, Costa Rica. Revista Forestal Mesoamericana Kurú 18(42):8-16. Doi: 10.18845/rfmk.v16i42.5537. [ Links ]

Vázquez-Alvarado, R. E., F. Blanco-Macías, M. C. Ojeda-Zacarías, J. R. Martínez-López, … y L. A. Háuad-Maroquín. 2011. Reforestación a base de nopal y maguey para la conservación de suelo y agua. Revista Salud Pública y Nutrición 5:185-203. https://docplayer.es/17088854-Reforestacion-a-base-de-nopal-y-maguey-para-la-conservacion-de-suelo-y-agua.html . (12 de septiembre de 2021). [ Links ]

Welemariam, M., F. Kebede, B. Bedadi and E. Birhane. 2018. Exclosures backed up with community-based soil and water conservation practices increased soil organic carbon stock and microbial biomass carbon distribution, in the northern highlands of Ethiopia. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture 5:1-11. Doi: 10.1186/s40538-018-0124-1. [ Links ]

Yáñez D., M. I., I. Cantú S., H. González R., J. G. Marmolejo M., E. Jurado y M. V. Gómez M. 2017. Respiración del suelo en cuatro sistemas de uso de la tierra. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 8(42):123-149. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v8i42.22. [ Links ]

Received: April 04, 2023; Accepted: June 20, 2023

texto em

texto em