Introduction

During the second half of the 20th century, many persons, including some biologists, regarded biological collections as “dinosaurs” or “white elephants” whose original function as taxonomic repositories had been surpassed and had no place in modern science (Shetler 1969; Lavoie 2013). This perception often led to budget cuts, reluctance to hire qualified personnel for handling and curatorial work, reduction of facilities, and little or no support for further growth, all of which threatened the existence of numerous collections. Lacking proper institutional support, some collections, especially small ones, were put at the brink of disappearance or disappeared completely over the past 30 to 40 years. For instance, some collections in the United States had to be merged with larger collections having better maintenance capability (Kemp 2015).

Paradoxically, in parallel with this period of apparent decline, other scientific community members were increasingly valuing the irreplaceable role of biological collections in documenting the changes that have been occurring on the planet as a consequence of human activities. Thirty years ago, Danks (1991) claimed that scientific collections were valuable mainly as sources of materials for reference, identification, and description of species, and as means for understanding the diversity and evolutionary relationships between current and past fauna and the ecosystems where they thrive. He also stated that scientific collections play a key role in scientific training, cultural outreach, and raising public awareness of environmental matters. Although all these are still essential functions of scientific collections, the recent development of molecular analysis tools, geographic information systems, and bioinformatics, together with the unprecedented degradation of the biota, have given renewed prominence to biological collections for studying the environmental modification processes that threaten the very survival of human populations (Vázquez-Domínguez and Hafner 2006). Specimens deposited in collections make it possible to address many environmental and health issues since they provide information on the condition of populations, species, and communities of organisms prior to anthropogenic modification (Lister et al. 2011).

Geist (1992) pointed out that “the dismantling of museum collections is not only tragic, but irresponsible, now that specimens have gained legal significance”, in reference to the fact that once a country puts an animal or plant species under legal protection by the State, its accurate identification becomes of paramount importance in deciding whether or not hunting, using, exploiting, trading, exporting, or destroying one or more specimens constitutes an offense. The proper application of biodiversity-related laws requires having scientific collections and scientific experts that can issue science-based recommendations.

Given the usefulness of molecular data for taxonomic identification and discovery of new taxa (Borisenko et al. 2008), the current collection of specimens usually includes sampling and preservation of tissues, turning scientific collections into repositories of genetic material from populations that may become extinct in the short- or medium-term. This practice also opens endless possibilities by making entire genomes of plants and animals available to the scientific and technological community for probing their potential for use as food, in pharmaceutical applications, or in the development of new technologies. For these reasons, biological collections in Mexico are deemed a matter of national security that bear strategic value (CONABIO 2019).

The Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN) is a higher-education and research institution that hosts several biological collections. Given their size and scientific value, some of these collections are amongst the most important both in Mexico and at an international level (e. g.,Yates et al. 1987; Guzmán 1994; Hafner et al. 1997; Ramírez-Pulido and González-Ruiz 2006; Dunnum et al. 2018; Thiers 2018). However, no study documenting the scientific value of the IPN collections and their impact throughout their history has been conducted to date. IPN hosts three major mammal collections: the oldest one was founded in 1955 at the Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas (ENCB); a second collection was set in 1984 at the Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional-Unidad Durango (CRD); and the third was established in 1985 at the Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional-Unidad Oaxaca (OAXMA). This study aimed at appraising the scientific value of the IPN mammal collections and their impact on scientific research and assessing their physical conditions relative to the minimum standards set by the American Society of Mammalogists (2004). Finally, the potential of the IPN mammal collections as a source of information for understanding the changes in the natural world that are taking place in the 21st century is discussed.

Materials and Methods

The scientific value of each collection was assessed in terms of the number of specimens it holds; number of orders, families, genera, and species represented both in each collection and overall (taxonomic scope); number of type specimens hosted; and collections associated with them. The nomenclature follows Ramírez-Pulido et al. (2014), with some exceptions and updates (as of 2019, see Appendix 1). Appendix 1 also indicates the endemism and conservation status of each species, as listed in the official Mexican standard (SEMARNAT 2019). The geographic representation of these collections was assessed in terms of the number of specimens from each Mexican State; ancillary collections were also identified.

The indicators most used in Mexico to evaluate scientific research performance are number and funding resources of research projects, number of peer-reviewed publications, and number of students trained (CONACYT 2020). To estimate the number of scholarly publications produced, we carried out a search in the major literature databases, including, but not limited to: REDALCYC, SCOPUS, SCIELO, Google Scholar, Research Gate, Journal Citation Reports, and CONRICYT, and in library catalogs of the institutions hosting the collections. We used the following search terms: “Mammalia”, “mammals”, “mamíferos”, “ENCB”, “CRD”, “OAXMA”, “Colección”, “Collection”, and the names of the curators and their collaborators. All publications in peer-reviewed journals, books, and book chapters that made use of materials or data from any of the three collections studied were gathered. The inclusion criteria were that at least one collection specimen had been used; at least one bat call has been recorded and organized in a reference sound library; at least one photograph has been captured either with a camera trap or digital camera and mounted as a science photo library sheet (Botello et al. 2007); at least one tissue sample or data has been deposited in any of the collections; or the curators or the collection have been acknowledged for granting access to specimens or information deposited in the collection. Some publications met more than one of these criteria; these were recorded in the numbers of the respective collections but were counted only once for computing total figures. The publications thus identified were then classified into 1) publications indexed in the Journal Citation Report or CONACYT index; 2) non-indexed publications; and 3) book chapters. “Gray” literature or popular science articles were not included. Finally, the average number of publications produced per year from each collection was calculated.

Student training was evaluated in terms of the total number of students that carried out social service (unpaid training work), internships, or short-term summer internships (short stays for undergraduate students sponsored by the Mexican Academy of Sciences) at each collection. Terminal projects, bachelor’s and master’s theses, and doctoral dissertations were identified by searching in the institutional theses archives of IPN (https://www.repositoriodigital.ipn.mx/handle/123456789/144), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM, http://oreon.dgbiblio.unam.mx/F?RN=656817172), and Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM, http://tesiuami.izt.uam.mx/uam/default.php), and in the library of each collection; the inclusion criteria were the same used for publications. Other contributions to student training that did not produce theses or dissertations were also identified and included.

The number and, whenever possible, the amount (in Mexican pesos) granted to research projects carried out by scientists affiliated to each collection (either as principal investigators or collaborators) were quantified. The amount of funding that IPN has received from collection-based research projects, consultancy work, or external services was estimated as well. Because funding data for older projects were not available and the figures are not comparable over time due to inflation, these data necessarily underestimate the real amount; nevertheless, they provide a rough idea of the income generated by collections. Those projects (2) that were carried out jointly by two or more collections were assigned to the collection where the leading investigator was affiliated. Finally, the infrastructure and physical conditions of each collection were described and compared with the minimum standards set by the American Society of Mammalogists (American Society of Mammalogists Systematics Collections Committee 2004).

Results

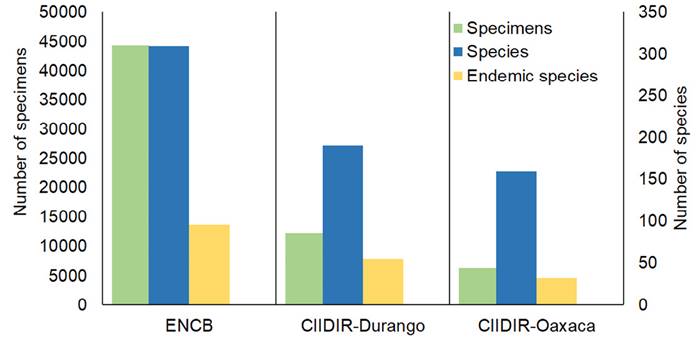

Scientific Value. As of the end of 2018, the IPN mammal collections jointly housed a total of 61,560 cataloged voucher specimens (ENCB = 44,275, CRD = 12,163, OAXMA = 5,122) representing 11 orders, 141 genera (84 % of all genera recorded in Mexico), and 348 species of Mexican terrestrial mammals. These species amount to 69.4 % of the 496 reported by Ramírez-Pulido et al. (2014) plus five additional species (Tlacuatzin balsasensis, T. sinaloaeArcangeli et al. 2018, Peromyscus leucurus, P. micropus, and P. zamoraeLópez-González et al. 2019) that were described or elevated to species after their publication; 116 of these species are endemic to the country (Appendix 1, Figure 1). The ENCB collection houses four type specimens of valid taxa: Notocitellus adocetus infernatusÁlvarez and Ramírez-Pulido 1968 (ENCB 1019), Microtus mexicanus ocotensisÁlvarez and Hernández-Chávez, 1993 (ENCB 27603); Molossus alvareziGonzález-Ruíz, Ramírez-Pulido and Arroyo-Cabrales, 2011 (ENCB 34208), and Tlacuatzin balsasensis Arcangeli, Light and Cervantes, 2018 (ENCB 26195). In the 1980s, ENCB carried out a project aiming at collecting topotypical samples from central Mexico (encompassing the States of Aguascalientes, Colima, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Jalisco, México, Michoacán, Morelos, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Tlaxcala, and Zacatecas). As a result, the size of the ENCB collection increased considerably and currently includes topotypes from 115 of the 792 type localities of mammal species or subspecies that had been described in Mexico up to that time (Álvarez et al. 1997).

Figure 1 Number of voucher specimens, species, and endemic species deposited at the IPN mammal collections.

OAXMA and CRD also host ancillary collections of tissue samples (OAXMA: 350 cataloged samples preserved in 95% ethanol and frozen at -18 °C; CRD: 9,003 samples preserved in 95 % ethanol and frozen at -20 °C), most of which are linked to voucher specimens in the main collection. OAXMA also maintains a sound library including 1,139 echolocation calls of 24 insectivorous bat species from the State of Oaxaca; 48 of these recordings are part of the national echolocation sound library of the Sonozotz project led by the Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología A. C. (Briones-Salas et al. 2013; Sosa-Escalante 2018; Zamora-Gutiérrez et al. 2020).

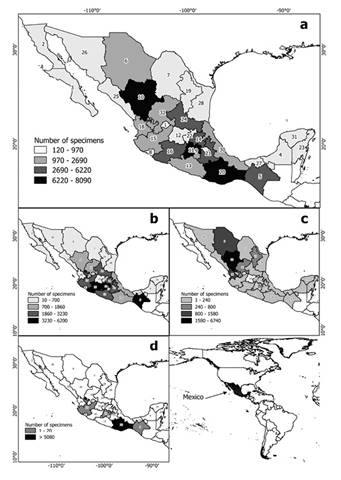

All the 32 Mexican states are represented in at least one of the IPN collections (Table 1; Figure 2). Due to their particular history and geographic location, the three collections supplement each other in both species composition and geographic representation. ENCB is mainly focused on the north-central (San Luis Potosí, Durango, and Zacatecas), central (State of Mexico, Michoacán, Jalisco, Aguascalientes, Hidalgo, Puebla, Tlaxcala, Veracruz, Guerrero, and Morelos) and southeast (Yucatán, Chiapas, and Oaxaca) parts of the country. CRD focuses on the Western Sierra Madre (Nayarit, Zacatecas, Durango, and Chihuahua States) and northern Mexico (Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas). OAXMA is mostly restricted to the State of Oaxaca (Table 1; Figure 2).

Figure 2 Number of voucher specimens of terrestrial mammals, per Mexican State, deposited in the IPN mammal collections: (a) total, (b) ENCB, (c) CRD, and (d) OAXMA. Numbers denote the State as listed in Table 1.

Table 1 Geographic representativeness, per Mexican State, of the IPN mammal collections. The total number of cataloged voucher specimens deposited in each collection is given below the acronym.

| State | Representativeness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENCB | CRD | OAXMA | ||

| 44,275 | 12,163 | 5,122 | ||

| 1 | Aguascalientes | 1.25 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Baja California | 0.88 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Baja California Sur | 0.91 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | Campeche | 0.15 | 0.6 | 0 |

| 5 | Chiapas | 9.74 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| 6 | Chihuahua | 0.29 | 12.75 | 0 |

| 7 | Coahuila | 0.02 | 2 | 0 |

| 8 | Colima | 0.66 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | Ciudad de México | 2.86 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | Durango | 2.84 | 55.35 | 0 |

| 11 | Estado de México | 13.99 | 0.04 | 0.35 |

| 12 | Guanajuato | 1.33 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | Guerrero | 5.29 | 0.01 | 0 |

| 14 | Hidalgo | 6.89 | 0.11 | 0 |

| 15 | Jalisco | 5.31 | 0.83 | 0.06 |

| 16 | Michoacán | 11.37 | 0.35 | 0 |

| 17 | Morelos | 3.6 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | Nayarit | 0.36 | 10.75 | 0 |

| 19 | Nuevo León | 0.03 | 6.55 | 0 |

| 20 | Oaxaca | 4.21 | 0.01 | 99.35 |

| 21 | Puebla | 5.93 | 0.53 | 0 |

| 22 | Querétaro | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0 |

| 23 | Quintana Roo | 1.59 | 0.01 | 0 |

| 24 | San Luis Potosí | 7.3 | 0.09 | 0 |

| 25 | Sinaloa | 0.2 | 1.67 | 0 |

| 26 | Sonora | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0 |

| 27 | Tabasco | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0 |

| 28 | Tamaulipas | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0 |

| 29 | Tlaxcala | 2.09 | 0.31 | 0.06 |

| 30 | Veracruz | 4.1 | 0.46 | 0 |

| 31 | Yucatán | 1.48 | 0.16 | 0 |

| 32 | Zacatecas | 2.6 | 4.07 | 0 |

| Other countries | 0 | 0.67 | 0 |

Indicators. Publications. A total of 285 peer-reviewed publications meeting the inclusion criteria were gathered (Table 2); specimens from ENCB were mentioned in 171 of these publications, from CRD in 61, and from OAXMA in 62; specimens from two or more of these collections were mentioned in nine publications. An average of 2.7 publications per year have been produced using material from the ENCB collection since its foundation, 1.8 publications per year using CRD materials, and 1.9 using OAXMA materials. Some 37 % of the publications based on the ENCB collection were published in indexed journals; 60 % of those produced based on the other two collections are indexed. Data from the ENCB collection have been used in ten books; no books have been published based on OAXMA or CRD materials. Book chapters account for 20 % of the publications produced using materials from ENCB, 13 % from CRD, and 17 % from OAXMA (Table 2).

Student training. We identified a total of 95 theses and dissertations that were supervised or co-supervised by researchers affiliated to the collections and that used materials housed therein: 34 for ENCB, 11 for CRD, and 50 for OAXMA. Two additional theses from ENCB were supervised by researchers not affiliated to the collection, for an overall total of 97. We found 30 additional theses/dissertations from other institutions that have used data or materials from the IPN collections (Table 2). A total of 73 college or junior college students carried out social service or short stays at the IPN collections; OAXMA has been the most active collection in this regard, followed by CRD and ENCB, only CRD has hosted post-doctorates (Table 2). The ENCB collection has also been used for delivering customized training courses for staff from PEMEX (the national oil company), SEMARNAT (the ministry of the environment), CONANP (the national commission for protected areas), and other government agencies.

Research Projects. We identified a total of 91 research or external service projects, 52 of which were directly funded by the IPN research and postgraduate secretariat (SIP), and 39 by external bodies. The main sources of external funding for the three IPN collections were CONABIO (the national commission for biodiversity) and CONACYT (the national council for science and technology), followed by Mexican and foreign government agencies, private companies, and non-governmental organizations. We estimated a total investment of at least 11,560,090 Mexican pesos; funding from external sources more than doubled the amount received from IPN (Table 2).

Table 2 Productivity of each IPN collection since its foundation to 2018. Level: L = Bachelor’s degree, M = Master’s degree, D = Doctorate, SS = Social Service, PR = Internship. Funding sources: SIP = IPN Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado. Funding figures have not been adjusted for inflation. Data used for this table are available from the first author upon request. PRA = peer-reviewed articles, IA= articles indexed by ISI; JCR or CONACYT, BC = Book chapters, OI = other institutions (L, M, D).

| Collection | Number of grants/funding amount in x 103 Mexican pesos | Number of peer-reviewed publications | Theses | Stays | Postdocs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External funding | SIP | PRA | IA | Books | BC | L | M | D | OI | SS, PR | ||||||

| (L, M, D) | ||||||||||||||||

| ENCB | 10/4,749.01 | 10/139.49 | 62 | 64 | 10 | 35 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 11, 5, 9 | 3, 1 | 0 | ||||

| CRD | 12/1,814.34 | 29/1,220.6 | 12 | 41 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 1, 2, 3 | 5, 5* | 2 | ||||

| OAXMA | 15/2,565.84 | 13/1,070.8 | 10 | 41 | 0 | 11 | 26 | 20 | 4 | 0, 0, 1 | 38, 20* | 0 | ||||

| Total | 37/9,129.19 | 52/2,430.9 | 84/82** | 146/139** | 10 | 54 | 66 | 27 | 4 | 12, 7, 12/11** | 46, 27 | 2 |

Other Products. Specimens from the ENCB collection have been used as a reference to identify material collected or recovered, through various projects, by the Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas CONANP), the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), and other government agencies. As of 2018, all the voucher specimens of the ENCB collection, approximately 60 % of CRD, and 17 % of OAXMA have been incorporated into the Sistema Nacional de Información sobre Biodiversidad (SNIB) maintained by CONABIO, which provides access to domestic and international users to georeferenced information through its online database. Photographs of specimens of many of the species included in the SNIB database are also accessible to the general public through the CONABIO website.

Physical Conditions: The ENCB Collection. The ENCB collection is housed in a room of approximately 70.0 m2 furnished with two work tables, 91 ad hoc wooden boxes for dried skins and skulls, two metal cabinets for tanned skins, a metal shelf for fluid-preserved specimens, and a wooden shelf for skeletons or skulls of large mammals. Three additional metal cabinets, each with five sections, mounted on compactor rails are also available. Controlled environmental conditions (relative humidity and temperature, separation of dried and fluid-preserved materials) are not available in this facility for preserving the specimens, thus fumigation with para-dichloro-benzene is carried out every six months. Given the toxicity and carcinogenicity hazard of this chemical, funds are currently being raised to install temperature and humidity controls and discontinue this fumigation procedure to avoid potential health risks. A small (10 m2) dermestarium is also available.

Most specimens (40,855) are preserved as dried skin and skull; complete or partial skeletons, and dried skins (3,020) are also included, as well as fluid-preserved whole-body specimens (400). The majority (99 %) of the specimens are labeled with information on the collecting locality and date, collector and preparator names, and are georeferenced and identified to species. The collection is managed by a curator and an assistant, both part-time permanent staff of IPN.

Physical Conditions: Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional Unidad Durango. The CRD collection is housed in a 49 m2 area, in addition to a library and office space (49 m2) where collection documents are kept, a small (8 m2) storage unit, a separate (19 m2) preparation room where fluid-preserved specimens (including the amphibian and reptile collections) are also kept, and a small (2 m2) dermestarium. The collection is currently supplied with 29 collection boxes, a cabinet for skins and large specimens, and two stereomicroscopes. The dried collection is kept in a temperature-and-humidity-controlled room separately from the fluid-preserved collection. The collection is regularly fumigated with para-dichloro-benzene, and there is a double door control to prevent the entry of insects.

Most specimens (10,451) are preserved as dried skin and skull or partial skeleton, in addition to complete or partial skeletons (902), dried skins without skeletal material (252), fluid-preserved whole-body specimens (15), and fluid-preserved specimens with no skull (543). The majority (99%) of these specimens are labeled with information on the collecting locality and date, collector and preparator names, and is georeferenced and identified to species. The collection is managed by a curator and a manager, both full-time permanent staff of IPN.

Physical Conditions: Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional Unidad Oaxaca. The OAXMA collection is housed in an approximately 36 m2 facility split into three sections: office space, preparation room, and specimen storage room. The preparation room is furnished with a freezer, materials, and four worktables. The specimen storage room is furnished with 18 wooden cabinets and two metal shelves where all the biological material (skulls, skeletons, and dried skins) is kept, as well as footprint casts, tissue samples, and photographs. The office and the specimen storage rooms are both supplied with air conditioning and humidity extraction systems.

Most specimens (3,019) are preserved as dried skin and skull or partial skeleton, followed by fluid-preserved whole-body specimens (546), complete or partial skeletons (438), and skulls (62). All specimens are labeled with information on the collecting locality and date, and collector name; 94.3 % have been identified to species. The collection is managed by a curator and a technician, both full-time staff of IPN.

As per the standards issued by the American Society of Mammalogists (American Society of Mammalogists Systematics Collections Committee, 2004), the IPN collections meet 90 % of the minimum conditions for the proper operation of a mammal collection.

Discussion

Scientific Value. With a grand total of 61,560 cataloged specimens, the IPN mammal collection is the largest in Mexico. For comparison, the second-largest institutional collection is the mammal collection of UNAM, with a grand total of 57,081 specimens, distributed among the Colección Nacional de Mamíferos of the Instituto de Biología (CNMA), the Alfonso L. Herrera Museum of the Facultad de Ciencias (MZFC), and the Paleontology laboratory of the Instituto de Geología (https://datosabificios.unam.mx/biodiversidad/). However, since the IPN collection does not include fossils, the specimens in the Paleontology laboratory of the Instituto de Geología should, strictly speaking, be excluded to make the total number of specimens comparable. Taken separately, the ENCB collection is the second-largest mammal collection in Mexico after the CNMA, which housed a total of 48,526 specimens as of 2015 (Rivera León et al. 2018). CRD is the fifth-largest collection, after the CNMA, ENCB, Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste in Baja California Sur (CIBNOR), and Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Iztapalapa (UAM-I) collections.

The IPN collection houses 14.6 % of the 421,466 voucher specimens of Mexican mammals deposited in scientific collections in North America (Lorenzo et al. 2012) and 32.7 % of those (188,350 specimens) in Mexican collections. Only the CNMA collection holds a larger representation (“close to 90 %”, Cervantes et al. 2016) of Mexican mammal species. The ENCB collection used to be among the 20 largest mammal collections in the Western Hemisphere (Choate and Genoways 1975; Genoways et al. 1976; Hafner et al. 1997; Lorenzo et al. 2012) and, although it has now been surpassed by other collections (Dunnum et al. 2018), it is still the third largest collection of Mexican mammals in North America, after the CNMA and KU (University of Kansas) collections (Lorenzo et al. 2012).

Lorenzo et al. (2012) pointed out that Mexican collections house a relatively low number of specimens from northern Mexico (Chihuahua = 2,619, Nayarit = 2,561, Sinaloa = 1,487, Nuevo León = 1,112, Coahuila = 1,107), most of them deposited in IPN collections, including 1,729 voucher specimens from Chihuahua (66 %), 1,529 from Nayarit (59.7 %), and 815 from Nuevo León (73.31 %). Lorenzo et al. (2012) found a total of 2,450 specimens from San Luis Potosí State, 1,039 from Zacatecas State, and 7,882 from Durango State deposited in Mexican collections; however, the IPN collection currently holds 4,506, 2,092, and 8,481of such specimens, respectively. Thus, as of 2018, most of the mammalian voucher specimens from northern Mexico (not including the Baja California peninsula and Sonora) are deposited in the ENCB and CRD collections. The OAXMA collection currently houses the largest number of mammalian specimens from Oaxaca in Mexico (Briones-Salas et al. 2015). These findings evidence the complementary nature of the three IPN collections in terms of both species composition and geographic representation.

Tissue Collections. No inventory of the tissue collections in Mexico has been compiled to date. However, Lorenzo et al. (2006) reviewed the mammal collections existing in Mexico and found that eight of the 36 collections also included tissue samples; the largest collections were those of CNMA, MZFC, and CIBNOR, which in 2006 housed a total of 1,750, 2,556 and 4,945 individual samples, respectively. The CIBNOR collection is currently the largest tissue collection in Latin America, with a total of about 24,000 samples (Álvarez-Castañeda et al. 2019); the CRD collection is still one of the largest in Mexico with 9,003 samples, and OAXMA has increased its size to 350 samples. Both CRD and OAXMA meet most of the curation standards for genetic material collections issued by the American Society of Mammalogists (Phillips et al. 2019).

The development of these ancillary collections has created new demands from the biological community; the IPN collections are now regarded as a major repository of reference and verification (voucher specimens) material for studies using tissue samples conducted both in Mexico and elsewhere. In fact, most of the recent theses and publications that made use of these collections involved molecular analyses. As the DNA or RNA sequences elucidated in those studies are then archived in publicly accessible databases (e. g., GenBank, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), their scientific value will continue increasing as they are used in future studies or as identification tools by users in Mexico and other countries.

Publications and Theses. An objective appraisal of the relevance of the publications, in particular those from ENCB, is a complex task. The publication standards by which the quality of a publication was judged in its first 30 years are not the same as in the latest 30 years, when publication citation indices and impact measures were created and widely adopted. Only 37 % of the publications based on the ENCB collection were published in currently indexed journals. By contrast, the other two collections, CRD and OAXMA, were founded 30 years later and, thus, have been subjected to modern productivity evaluation standards almost since their inception. Thus, 60 % of the publications based on the CRD and OAXMA collections were published in indexed journals.

Also consistent with this change in the standards and information dissemination modalities, ten books have been produced using data from the ENCB collection, with 20 % of its production in the form of book chapters. In contrast, no books associated with the other two collections have yet been published, and less than 20 % of their publications are book chapters (Table 2). Thus, although the overall publication productivity of the ENCB collection is almost one publication per year higher than that of the other two collections, their rates are about the same when only indexed journals are considered (1.1 per year versus 1.2).

The first curators of the ENCB (Ticul Álvarez Solórzano), CNMA (Bernardo Villa Ramírez), and UAM-Iztapalapa (José Ramírez Pulido) collections are recognized as the pioneers of mammalogy in Mexico. Up to the early 1970s, Mexican mammalogy was led by work conducted in or associated with these three collections (Ríos-Muñoz et al. 2014), where the next generation of Mexican mammalogists was trained.

Most publications and theses produced in that early period were descriptive, mainly focusing on taxonomy, anatomy, physiology, or reproductive aspects (Ríos-Muñoz et al. 2014). Over time, and as research priorities and technologies evolved, material deposited in the collections has been increasingly used for other types of studies. The earliest non-descriptive study that we were able to document was the one by Genoways (1973), who used ENCB specimens to examine evolutionary relationships in the genus Liomys (currently Heteromys). The first molecular analyses conducted using material from IPN collections were those by Hafner et al. (2001), Bell et al. (2001), and Guevara-Chumacero et al. (2010), who used materials from the ENCB, CRD, and OAXMA collections, respectively. Ecological studies began with Álvarez and Arroyo-Cabrales (1990), Muñiz-Martínez (1997), and Prieto-Bosch and Sánchez-Cordero (1993). The latter is also the first publication in which geographic information systems were used, with data from the OAXMA collection. Álvarez-Castañeda (1993, ENCB), Illoldi-Rangel et al. (2004, OAXMA), and López-González et al. (2015, CRD) were the first studies that used information from IPN collections to address biogeographic questions. More recently, OAXMA added an echolocation sound library that has been used for taxonomic studies (Briones-Salas et al. 2013).

The examples above reflect the global trend towards diversifying the uses of scientific collections (Schindel and Cook 2018). Technological innovations enable novel uses for traditional materials such as dried skins and skulls, which acquire higher value when also supplied with newly available information, such as georeference. When non-traditional material such as tissues, sound recordings, photographs, or videos are also collected and incorporated into scientific collections, these become repositories of verifiable evidence valuable not only for taxonomic but also for ecological and behavioral studies, to name a few (Pyke and Ehrlich 2010; Schindel and Cook 2018; Winker 2004).

Research Projects. Despite being the oldest one, the ENCB collection has contributed the fewest research projects. This may be partly due to an artifact caused by the scarce information available on the operation of this collection prior to 1995, but also reflects the fact that during the first half of its existence, prior to the foundation of CONABIO in 1992, financing for the development and operation of biological collections in Mexico was far more limited. In contrast, the CRD and OAXMA collections started growing actively after 1990 and enjoyed better access to funds from both the IPN and external agencies such as CONABIO and CONACYT. Funding from CONABIO in the 2000-2010 period strongly promoted the digitization of the IPN collections and financed inventory projects in specific areas of interest. In line with the historical trends in scientific publication described above, those research projects have mainly addressed mammal inventories and descriptive studies; projects focused on more analytical topics such as population structure and organism-environment relationships started in the late 1990s.

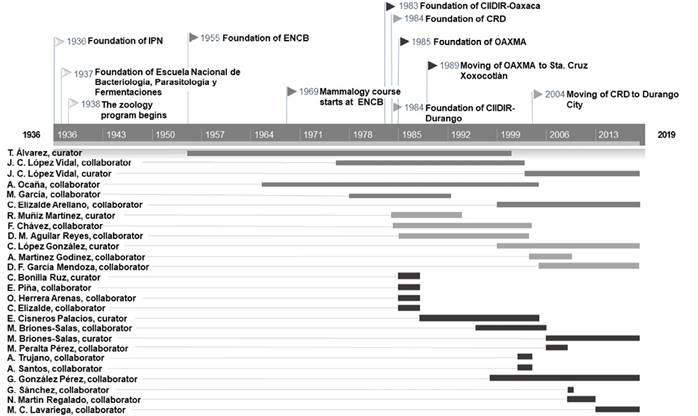

Student Training. The role of IPN collections on student training has been quite different for the CRD and OAXMA than for the ENCB and other major institutional collections because CIIDIRs were not associated with higher education institutions in their early years (Figure 3). The ENCB mammal collection includes a small section entirely dedicated to college teaching purposes, which has been extensively used over the past 55 years by students (ten per semester on average) enrolled in the elective Mammalogy course as part of the B.Sc. Biology program.

Figure 3 lists the IPN staff who have worked for the collection. In addition, many other persons have collaborated as students doing social service and theses or dissertations, temporarily hired to work on research projects, or as volunteers collecting, preparing, and curating specimens, sometimes for periods up to five years or longer. This group includes, in alphabetical order: Martín Aguilar Cervantes, Sergio Ticul Álvarez-Castañeda, Joaquín Arroyo-Cabrales, Tania Berrocal Espino, Pablo Domínguez, Salvador Gaona Ramírez, Manuel González Escamilla, Noé González-Ruíz, José Juan Hernández-Chávez, Karina Lagunes Serrano, Nansy López, Consuelo Psiabini López Valentín, Nisa Victoria López Valentín, Isaac M. Cruz Márquez Benítez, Eliecer Martin, Matías Martínez-Coronel, Noemí Matías Ferrer, Raúl Muñiz-Martínez, Sergio Murillo Jiménez, Francisco Javier Navarro Frías, Oscar J. Polaco, Enrique Quiroz Uhart, Claudia Yeyetzi Salas Rodriguez, Carolina Salazar Motolinía, Norma Valentín Maldonado, Jorge Villalpando, and Ángel Vega López, all of which worked at the collections for over a year. Many of these individuals eventually became prominent professional mammalogists.

For its first 20 years, the CRD collection was located in Vicente Guerrero City, Durango, 80 km from the state capital. It was relocated to the state capital, Durango City, in 2004, shortly after the local university, Instituto Tecnológico de Valle de Guadiana, launched its B.Sc. Biology program in 2003. However, it was not until 2016 that a cooperation agreement was signed allowing B.Sc. Biology students from Instituto Tecnológico to carry out social service, study stays, and thesis at CIIDIR Durango. CIIDIR Durango launched its M. Sc. program in Environmental Management in 2005 and was included by CONACYT in its quality postgraduate program (PNPC, for its acronym in Spanish) in 2007. CIIDIR Durango became one of the campuses of the Ph.D. program in Conservation of Landscape Heritage, which was also included in the PNPC in 2014, thus allowing the participation of local out-of-state, and foreign students. In this way, a number of students have collaborated in collecting activities over the years, either as students, interns, or as temporary workers (for at least one year), including Nancy Enríquez, Ángel García Rojas, Alejandra J. Guerrero González, Nancy Lemus Medina, Abraham Lozano, Teresa Salas-H., Gloria Tapia-Ramírez, and Alí I. Villanueva-Hernández.

Similarly, few students collaborated with the OAXMA collection in its early years. The local university, Instituto Tecnológico de los Valles de Oaxaca (ITVO) has been collaborating actively with OAXMA since 2008; 86 % (n = 26) of the B.Sc. theses associated with OAXMA were carried out by ITVO undergraduate students. CIIDIR Oaxaca launched its M.Sc. program in use and conservation of natural resources in 2003 and the corresponding PhD program in 2005; both postgraduate programs belong to PNPC and opened the possibility for postgraduate students to participate in OAXMA activities. The establishment of PNPC-listed postgraduate programs at both CIIDIRs and the ensuing possibility of accessing scholarships from CONACYT have enabled using both collections in student training at the regional and country-wide level, as does the ENCB collection.

Physical Conditions. All three collections meet most of the ASM minimum conservation standards (American Society of Mammalogists Systematics Collections Committee 2004). All of them have specialized trained staff dedicated to preservation and curatorial work, and voucher specimens have the proper curation level to be used for scientific work. Their primary weakness is the lack of sufficient, suitable infrastructure (buildings and insect-resistant, fire- and water-proof furniture) to prevent the long-term deterioration of specimens, and the slow implementation of online electronic catalogs to make the information easily accessible to users. Although the three collections enjoy implicit institutional recognition, no explicit policy for their continued maintenance and long-term conservation is in place.

The three collections are well on their way to meeting the minimum conservation standards issued by the ASM in 2004 (American Society of Mammalogists Systematics Collections Committee 2004). However, such standards were intended for traditional collections of dried skin and skeletal materials. The increasing use of specimens collected including tissue and hair samples, echolocation recordings, ectoparasites, or other ancillary materials, and the trend towards the digitization of collections to make their information available online, has necessarily given rise to novel curatorial techniques (e. g.,Phillips et al. 2019) and methods for the storage and handling of materials and information. All these demand new types of infrastructure, equipment, and staff, and entail increased maintenance costs.

The economic value of the IPN mammal collections has not been estimated; an accurate annual maintenance cost is unavailable, and they are not insured. Because the IPN collections do not have a dedicated budget assigned, these costs are hard to estimate. Uribe (1997) pointed out that the economic value of an object is set with reference to its market value. Because collection specimens rarely have market value (except for feline skins and similar items), their replacement value (i. e., capturing, processing, and maintenance costs) can be used instead to assign a monetary value to scientific collections. Their cultural and scientific value (for example, species richness, rarity of specimens, quality of the information associated with them, among others) should be considered as well.

Baker et al. (2014) estimated the “door to drawer” cost of voucher specimens, i. e., the cost of processing a specimen from its arrival from the field until it can be used, at US$17.51 (around 332.69 Mexican pesos of 2019), plus US$0.25 (4.75 Mexican pesos) per year per specimen for long-term maintenance. This estimate includes the costs of curating, installing, and databasing, as well as curator and student fees, for traditional specimens (dried skin plus skeleton) and tissue samples. Digitization costs in Europe have been estimated between 0.50 and 73.44 euros (10.45 to 1,535.63 Mexican pesos of 2019) per item (Blagoderov et al. 2012), depending on the collection type and preservation method used. As more ancillary materials are collected and the information and voucher specimens themselves are digitized, these costs would increase with the type and amount of material and the information being preserved. However, even if replacement cost estimates were available, the institution and curators of the IPN collections are fully aware that many of the materials housed in these collections are irreplaceable as the populations from which they were extracted may no longer exist due to natural or anthropogenic changes.

Future outlook. The Mexican government explicitly recognized the strategic importance of scientific collections since 1992 with the creation of CONABIO. Funding provided by CONABIO through grants for biological inventories and collection computerization supported the continued operation and expansion of many collections. Much of the information deposited in Mexican collections has now been incorporated into the National System of Biodiversity Information (SNIB, for its acronym in Spanish), which, in turn, is part of global biological database networks, such as the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF, https://www.gbif.org).

McLean et al. (2016) highlighted the importance of mammal collections as research instruments. They documented that 25 % of all 1,403 articles published between 2005 and 2014 in just a single journal specialized in the study of mammals (the Journal of Mammalogy) used material deposited or eventually deposited in collections. The main subjects addressed in those articles included systematics and biogeography, genomics, morphometrics, parasitology and pathogens, stable isotope analysis, and teaching. These authors also pointed out that a significantly higher proportion of those studies used a combination of historical material and recently collected specimens, thus evidencing the importance of continue incorporating new material to collections.

Mexican mammal collections are expected continue growing; we are still far from having explored the entire territory and fully described the diversity it harbors. Mammals are one of the best-sampled zoological groups and, nevertheless, eight new species were added to the known Mexican fauna between 2005 and 2014 (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2014). Two of these recently described species were determined from newly collected specimens, but the others were determined based on materials already deposited in a collection. The use of new study techniques has allowed describing numerous species based on already existing specimens that had not been previously examined or that were re-examined in the light of new knowledge.

Fontaine et al. (2012) pointed out that, in developed countries that have large scientific collections, more new species are being described based on existing material than on newly collected specimens. The opposite holds for developing countries with no or only limited collections. Mexico is midway between these two extremes; vast parts of the Mexican territory remain practically unexplored and numerous zoological groups have been scarcely studied. Collecting efforts in those areas and zoological groups would likely lead to the discovery of new species. In addition, examining newly collected materials in relation to the materials already available might also lead to discoveries in our own cabinets.

The coverage and quality of voucher specimens, as well as the information associated with them, are key for developing a more accurate perception of scientific collections as essential resources for understanding the consequences of human development on our planet. Information deposited in scientific collections can provide a scientifically sound baseline for understanding modification processes, by supplying data on the former condition of the biota (Lister et al. 2011). Properly georeferenced data are the base for studying distributional changes driven by urban or agricultural development and for predicting future distribution scenarios. These data are also useful for documenting the decline of natural populations (Shaffer et al. 1998), changes in the morphology (MacLean et al. 2018) or life history of plants and animals, measuring changes in nutrient availability or heavy metal concentrations, or detecting emerging diseases, among other uses (Meineke et al. 2018). Combining geographic information with genetic information derived from the same specimens offers a powerful tool for studying anthropogenic effects on the genetic health of populations (Cook and Light 2019).

The past 50 years have brought about rapid changes in the approach and techniques used collect, analyze, preserve, and document specimens of biological collections. The IPN mammal collections have been under continued activity since their foundation; their specimens have been successfully used for research and student training. Although the IPN collections meet most of the minimum curatorial standards, the process of digitizing the collections has not yet started, and their catalogs have not yet been fully incorporated into global databases; only part of their data have been incorporated into the SNIB. The challenge for the IPN collections to become even more useful in the contemporary world lies, in addition to ensuring their long-term preservation, in attaining the standardization, management, and availability of information and voucher specimens in digital formats (iDigBio 2019; DiSSCo 2019; Sunderland 2013). Digitizing the IPN collections and making them accessible over the internet will add another dimension to their potential use (Beaman and Cellinese 2012; McLean et al. 2016) and lead to research results that would not be possible otherwise (e.g., Redding et al. 2016).

CONABIO has made a significant effort in this direction through the SNIB, which includes a standardized database, an inventory of Mexican collections, their affiliated staff, and their taxonomic scope and geographic representativeness (CONABIO 2019). Nevertheless, a national policy for the reliable and continuously updated management, conservation, and digitization of this portion of our natural capital is still missing. Since IPN, UNAM, and INECOL host the largest biological collections in Mexico, these institutions should lead, together with CONABIO, the development of a national policy on biological collections to achieve these objectives.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)