Introduction

Aortic valve (AV) stenosis is the most common valve heart disease and it is an important public health problem1,2. Prosthetics AV replacement is the gold standard surgical procedure for treatment AV disease; however, this procedure has important complications such as mismatch, anticoagulation complications (mechanical prosthesis), and degeneration (biological prosthesis), among others3-5.

AV repair is an alternative to AV replacement; nevertheless, this procedure requires more surgical expertise and is almost restricted to aortic regurgitation6-8.

AV reconstruction surgery is a novel surgical procedure for treatment AV disease; it is consisting of removing the AV and replacing it with a neo-valve constructed with autologous pericardium treated with glutaraldehyde. This procedure described many years ago by Duran et al. showed excellent hemodynamics and low thrombogenicity; however, with the appearance of more versatile prosthetic valves and because the initially described technique was not easily reproducible, this procedure was not widely developed9. Recently, Ozaki et al. have devised a measurement system that makes this technique easily reproducible. The results of survival and reoperation-free survival are excellent in medium-term follow-up, with the fundamental advantage of avoiding the use of anticoagulants10,11.

As previously described, there is a standardized system of templates to perform this procedure; however, due to administrative and financial problems, it is difficult to acquire this in our center. That is why we designed our own templates system. With this system, we have not only performed AV reconstruction surgeries, but also pulmonary valves12,13.

We present the early follow-up evolution of our first cases of surgeries performed.

Patients and methods

Study design

We conducted a retrospective investigation from January 2018 to June 2020 in patients undergoing AV reconstruction surgery, performed by the same surgical team, in a national reference center in Lima, Peru. We selected patients who were susceptible to AV replacement with a biological prosthesis or those who rejected a mechanical prosthesis. We excluded redo-surgeries, emergency, and morbid obesity (BMI > 40).

Operative technique

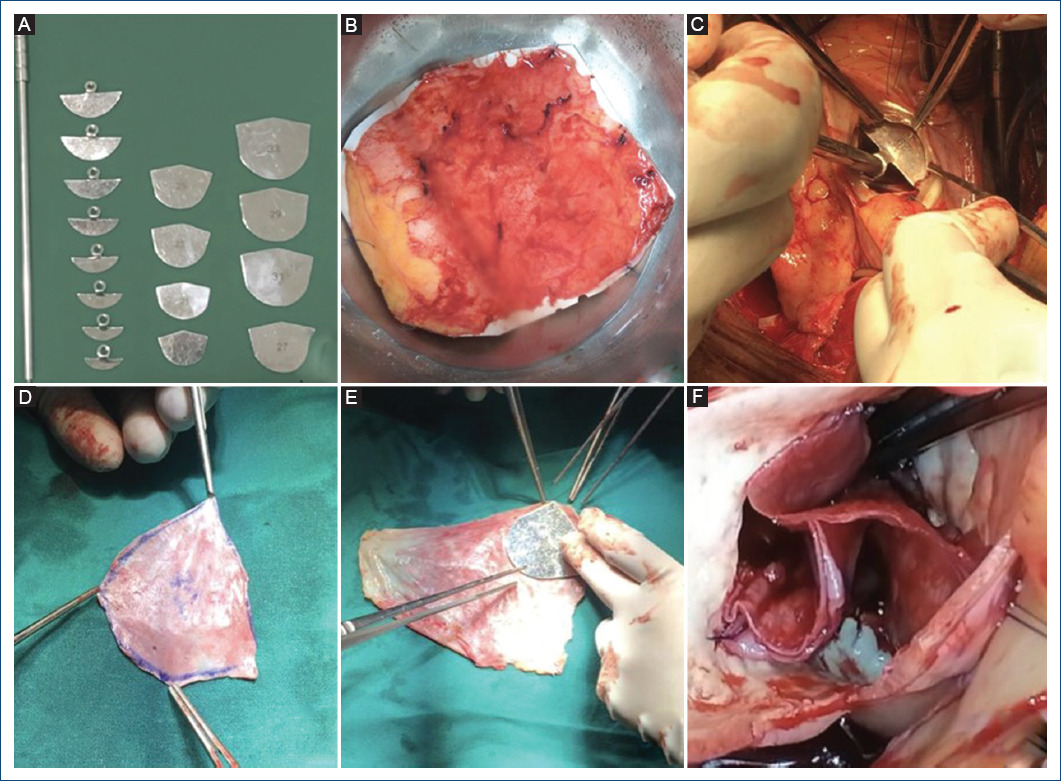

After a median sternotomy, the preparation of the pericardium is started by cleaning it of fat and other redundant tissues on its external surface. A portion of the patient's pericardium was harvested and removed. The excised pericardium was then treated with 0.6% glutaraldehyde solution with an 8.4% sodium bicarbonate solution for 10 min (Fig. 1B). The treated pericardium was rinsed 3 times using physiologic saline solution for 6 min. After removing all native leaflets, each one was constructed using our sizers system (Fig. 1A, C-E). The suture (4-0 polypropylene) is begun at the middle of the annulus nadir. The distance ratio between each bite on the pericardium and the annulus was 3:1 at the nadir, and it was changed to 1:1 when the suture comes up to the coaptation zone, the end of each suture is passed through the aortic wall and tied that of the adjoining leaflet with a pled-get, then the commissural coaptation is secured with additional 4-0 polypropylene suture. We followed the technique described by Ozaki et al. in their reports (Fig. 1F)8,14.

Figure 1 A: our sizers system. B: pericardium treated with glutaraldehyde. C: sizing the annulus. D: measuring a neo-leaflet. E: neo-leaflet. F: neo-AV after complete reconstruction.

All surgeries were performed during cardioplegic arrest on cardiopulmonary bypass. All patients underwent intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in addition to standard monitoring for cardiac surgery.

According to the American Society of Echocardiography Recommendations, an advanced trained imaging cardiologist assessed transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography.

Evaluation stages

We define three time periods: (a) baseline, (b) perioperative period: first 30 post-operative days, and (c) extended follow-up: 19 (± 8.9) months.

Outcomes

The primary clinical outcomes were determined mortality and other complications as well as the hemodynamic characteristics of the neo-AV (gradient, degree of insufficiency) in the perioperative period and follow-up.

Statistical analysis

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

We performed statistical analysis using Stata v17.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA). We explore the distribution of variables using analytical and graphical methods and report numerical data. Numerical variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation or as median and interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables are expressed in absolute and relative frequencies. For mortality and complications, we estimate the cumulative incidence in the perioperative period and follow-up.

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS

We executed the bivariate comparative analysis considering two post hoc direct exploratory comparisons (binary): perioperative versus baseline, extended follow-up versus baseline. We tested the differences with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for dependent numerical measures and with McNemar's exact test for dependent categorical measures. We did not observe normality of the numerical data, so we opted for these non-parametric methods.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of our patients. From January 2018 to June 2020, we operated 40 patients. Two who were directly converted to prosthetic valve replacement in the operating room due to moderate-severe AV regurgitation and one patient with morbid obesity were excluded from the study. In 2020–2021, our AV reconstruction surgery program was stopped due to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, we have recently restarted.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of patients (n = 37)

| Age (years) median (IQR) | 62 (42-68) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 18 (48.6) |

| Female | 19 (51.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) median (IQR) | 25 (23.4-27.3) |

| Underweight (< 19) n (%) | 01 (2.7) |

| Normal (19-24.99) n (%) | 17 (45.9) |

| Overweight (25-29.99 n (%) | 15 (40.5) |

| Obesity (≥ 30) n (%) | 04 (10.8) |

| Functional class (NYHA), n (%) | |

| I | 01 (2.7) |

| II | 19 (51.4) |

| III | 17 (45.9) |

| AV disease, n (%) | |

| Stenosis | 23 (62.2) |

| Insufficiency | 12 (32.4) |

| Prosthesis dysfunction | 02 (5.4) |

| AV morphology, n (%) | |

| Unicuspid | 01 (2.7) |

| Bicuspid | 19 (51.4) |

| Tricuspid | 17 (45.9) |

| Prosthesis | 02 (5.4) |

| AV annulus (mm), median (IQR) | 23 (20-25) |

| ≤ 21, n (%) | 12 (32.4) |

| Peak AV gradient (mmHg)-median (IQR) | 70 (21.5-70) |

| Mean AV gradient (mmHg)-median (IQR) | 45 (13.5-57.5) |

| LVEF (%), median (IQR) | 58 (50-65.5) |

| LVEF < 40%, n (%) | 05 (13.5) |

| Concomitant pathology, n (%) | |

| Ascending aorta aneurysm | 08 (21.6) |

| TV insufficiency | 08 (21.6) |

| MV disease | 08 (21.6) |

| Coronary artery disease | 06 (16.2) |

| Other basal characteristics, n (%) | 14 (37.8) |

| Hypertension | 08 (21.1) |

| Diabetes | 08 (21.1) |

| Chronic atrial fibrillation | |

| Euroscore II (%) median (IQR) | 1.65 (0.6-3.7) |

| ES II > 5% n (%) | 04 (10.8) |

BMI: body mass index; Kg: kilogram; m: meter; NYHA: New York Heart Association; AV: aortic valve; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; TV: tricuspid valve; MV: mitral valve; ES: Euroscore; IQR: interquartile range.

For the analysis, we included 37 patients, the median age was 62 years (IQR: 42-68), 51.4% were women. Nineteen patients (51.4%) were overweight or obese before surgery.

The main indication for surgery was AV stenosis (62.2%) in most cases due to bicuspid valve (19 patients, 51.4%). Something to highlight is that in two patients, we performed this procedure in redosurgeries (prosthesis dysfunction, one with a biological, and the other with mechanic prosthesis). It was possible to carefully remove the autologous pericardium in these patients.

The median size of the AV annulus was 23 (IQR: 20-25); however, we operated 12 patients (32.4%) with small AV annulus (< 21 mm). The medians of the peak and mean AV gradient were 70 mmHg (IQR: 21.5-70) and 45 mmHg (IQR: 13.5-57.5), respectively. When we only include patients with AV stenosis, medians of the gradients were 89 mmHg (IQR: 70-95) and 55mmHg (IQR 45-62), respectively.

Twenty-two (59.5%) patients had another associated pathology with surgical indication in addition to AV disease, 8 (21.6%) of them had dilatation of the ascending aorta with indication for replacement. About 21.6% (eight patients) used oral anticoagulants (OAC) as a treatment for chronic atrial fibrillation (AF).

Surgical procedures characteristics

We performed 16 (42%) AV reconstruction surgery as single procedure and 22 (58%) with another associated procedure (Table 2A). In six patients, we performed mitral valve (MV) repair surgery and in two mechanical MV replacement (in these cases of first intention, an attempt was made to repair the mitral valve; however, due to the fact that the intraoperative result was not successful, the valve had to be replaced.). Six patients (16.2%) had coronary artery disease with indication for CABG; however, two more underwent CABG due to suspected intraoperative coronary embolism (total CABG, 21%). In eight patients (21.6%), we performed ascending aortic surgeries, seven underwent ascending aorta replacements, and one underwent AV re-implantation surgery (David procedure + AV reconstruction surgery).

Table 2 Surgical procedures and early post-operative

| Surgical procedures characteristics (n = 37) | |

|---|---|

| CPB time (min), median (IQR) | 150 (134-180) |

| Cross clamp time (min), median (IQR) | 121.5 (97-142) |

| AV reconstruction single procedure, n (%) | 15 (40.5) |

| AV reconstruction+other procedure, n (%) | 22 (59.5) |

| MV surgery | 08 (21.6) |

| AA surgery | 08 (21.6) |

| TV repair | 09 (24.3) |

| CABG | 08 (21.6) |

| Surgical approach, n (%) | |

| Full sternotomy | 34 (91.9) |

| J shaped mini-sternotomy | 03 (8.1) |

| Early post-operative evolution (first 30 days) | |

| ICU stay, median (IQR) | 03 (02-4.1) |

| In hospital stay, median (IQR) | 10 (08-12.2) |

| Perioperative complications, n (%) | |

| Stroke | 00 (00) |

| Definitive pacemaker | 01 (2.7) |

| Redo-surgery for excessive bleeding | 02 (5.2) |

| Tracheostomy | 01 (2.7) |

| Perioperative myocardial infarction | 02 (5.4) |

| Mortality | 01 (2.7) |

CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; AV: aortic valve, MV: mitral valve; AA: ascending aorta; TV: tricuspid valve; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; ICU: intensive care unit.

The median of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time was 150 min (IQR: 134-180), the median of aortic cross clamp time was 121.5 (IQR: 97-142), when we include AV reconstruction surgery as a single procedure that these times were 136 min (IQR 105-154) and 104 min (IQR: 80-117), respectively.

Perioperative evolution (early outcomes)

MORTALITY

One patient died (2.6%) in the first 30 post-operative days due to suspected intraoperative coronary embolism; in this case, we performed CABG surgery (graft of the saphenous vein to anterior descending and marginal arteries) but died due to cardiogenic shock.

OTHER COMPLICATIONS

Two patients were re-operated due to excessive bleeding (5.3%). One patient underwent tracheostomy and prolonged ventilation due to in-hospital pneumonia. There were no stroke events (Table 2B).

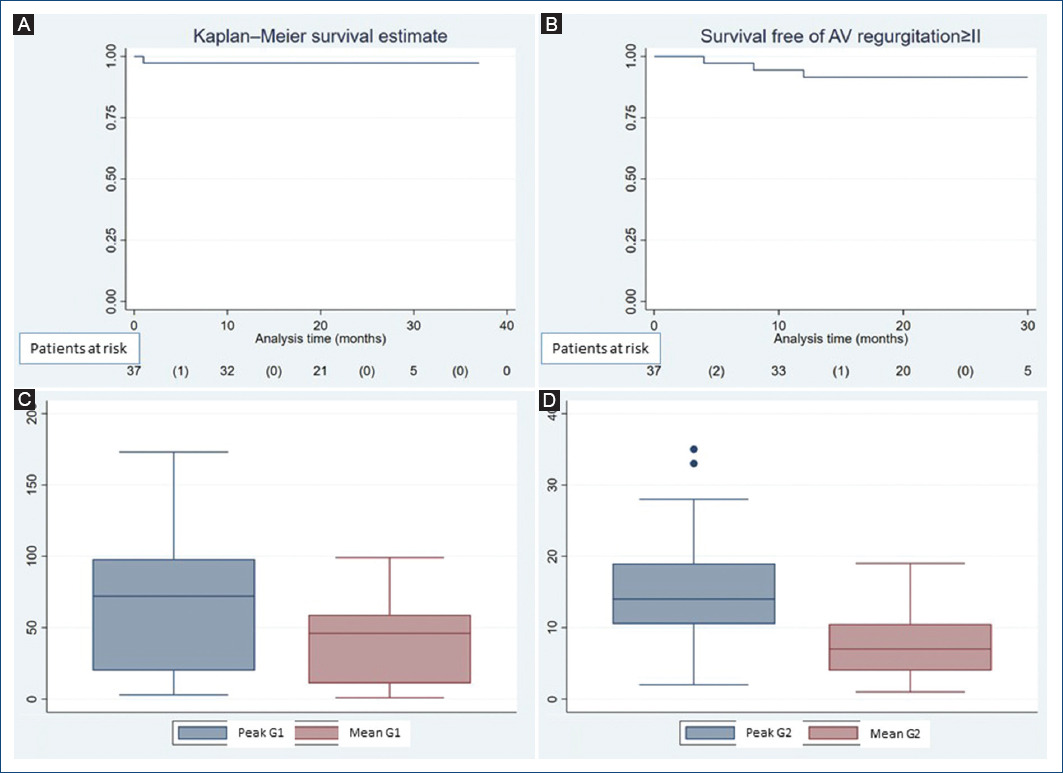

HEMODYNAMIC OF THE NEO-AV

There was a significant reduction in the medians of the peak (70 mmHg, CI 95% = 50.03-79.86 vs. 14 mmHg, CI 95% = 11.93-17.5, p < 0.0001) and mean (45 mmHg CI 95% = 30.6-49.68 vs. 7 mmHg, CI 95% = 5.93-9.6, p < 0.0001) AV gradients (Table 3 and Fig. 2A). In this period, no patient had a mean gradient > 20 mmHg.

Table 3 Outcomes in baseline, perioperative period, and extended follow-up (n = 37)

| Baseline | Perioperative period* | Extended follow-up† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography parameters | Median (CI 95%) | Median (CI 95%) | Median (CI 95%) | p-value§ | p-value‡ |

| AV peak gradient (mmHg) | 70 (50.03-79.86) | 14 (11.93-17.5) | 12 (10.9-17.7) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| AV mean gradient (mmHg) | 45.5 (30.6-49.68) | 07 (5.93-9.6) | 06 (5.2-9.2) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| LVEF (%) | 58.5 (52.1-60.9) | 60 (53.32-60.61) | 60 (55.81-61.79) | 0.8127 | 0.1928 |

| Aortic regurgitation, n (%) | p-value¶ | p-value** | |||

| 0-I | 13 (35.1) | 35 (94.6) | 33 (89.1) | < 0.01†† | < 0.01†† |

| II-III | 13 (35.1) | 01 (2.7) | 03 (9.1) | ||

| IV | 12 (32.4) | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | ||

| Clinical variables, n (%) | |||||

| All-cause mortality | - | 01 (2.7) | 01 (2.7) | NA | NA |

| Stroke | - | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | NA | NA |

| Myocardial infarction | - | 02 (5.4) | 02 (5.4) | NA | NA |

| ACO use | 08 (21.6) | 08 (21.6) | 10 (27.0) | NA | NA |

| Definitive pacemaker | - | 01 (2.7) | 02 (5.4) | NA | NA |

| Redo-surgery for valve dysfunction | - | 00 (00) | 00 (00) | NA | NA |

| Functional class (NYHA), n (%) | |||||

| I | 01 (2.7) | 15 (40.5) | 32 (86.5) | ||

| II-III | 36 (97.3) | 21 (56.8) | 04 (10.8) |

*First 30 postoperative days;

†19 months on average; NA: Not Applicable.

‡Wilcoxon signed-rank test for dependent measures (perioperative period vs. baseline).

§Wilcoxon signed-rank test for dependent measures (extended follow-up vs. baseline).

¶Exact McNemar test for dependent categorical measures (perioperative period up vs. baseline).

**Exact McNemar test for dependent categorical measures (extended follow-up vs. baseline).

††Hypothesis test performed for binary collapsed data (II-IV vs. 0-I).

Figure 2 A and B: Kaplan Meier method showing survival data. C and D: graph box showing the evolution of the AV gradients, G1: preoperative gradients, G2: early postoperative gradients.

The sum of patients without AV insufficiency or with insufficiency grade I was 36/37 (97.3%), only one patient (2.7%) had AV regurgitation grade II, no cases with insufficiency grade III or IV were observed, when these data were compared with the pre-operative period, the difference was significant (Table 3).

Follow-up evolution

The mean follow-up was 19 (± 8.9) months.

MORTALITY

Mortality and other complications are expressed in Table 3. We did not have other additional mortality in the follow-up.

HEMODYNAMIC OF THE NEO-AV

Significant reduction in the medians of the peak (70 mmHg, CI 95% = 50.03-79.86 vs. 12 mmHg, CI 95% = 10.9-17.7, p < 0.0001) and mean (45 mmHg CI 95% = 30.6-49.68 vs. 6 mmHg, CI 95% = 5.2-9.2, p < 0.0001) AV gradients when we compared baseline characteristics with follow-up were maintained (Table 3 and Fig. 2C,D). Only one patient had a AV mean gradient > 20 mmHg (peak AV gradient = 45 mmHg, mean AV gradient = 26 mmHg), in this case, the aortic annulus was < 21 mm in diameter.

FREEDOM FROM REOPERATION AND AORTIC INSUFFICIENCY ≥ II

No patient has been re-operated for valve dysfunction. Only three (8.1% of patients) have insufficiency ≥ II (II = 2, III = 1). The cause of grade III insufficiency is due to the fact that the patient has developed a dilation of the aortic root (currently 40 mm) that he did not have at the time of surgery (33 mm); however, this patient is in functional Class I (NYHA).

Survival, reoperation-free survival for valve dysfunction, and survival free of AV insufficiency > II were 97.3%, 100%, and 91.9%, respectively (Fig. 2A,B).

Discussion

Symptomatic severe aortic stenosis is associated with high mortality rates, ~ 50% at 1 year, and the prevalence will likely increase as the population ages. In this pathology, interventional procedures (surgery is still the gold standard, especially in younger patients) have been shown to drastically reduce mortality and improve quality of life15,16. Nevertheless, in many cases when we replace the diseased AV with a prosthesis, we are changing one problem for another. Many complications have been described in heart valve prosthesis, but of particular interest to us are the complications derived from poor OAC therapy control (mechanical prosthesis) and those due to the rapid degeneration of biological prosthesis2-4,17. Most of the patients in our national health system are poor and do not have timely access to health services, which is why it is difficult to provide adequate OAC therapy in these patients, many of whom are from the interior of the country and they come to the capital just for the surgery. Early degeneration of biological prosthesis generates more public spending (mainly because transcatheter therapy is now preferred) and a higher risk of mortality due to reoperation. AV reconstruction surgery offers many advantages, mainly avoid OAC therapy and promises to be a technique with excellent long-term results, so it is a relatively economical technique compared to AV replacement, we believe that it is an ideal choice for developing countries. This idea is supported by other authors18,19.

MORTALITY AND COMPLICATIONS

The 30-days mortality in our study cohort was 1/37 patients (2.7%). Mean follow-up was 19 (± 8.9) months and survival rate was 97.3% (36/37) at this time. The largest series of patients published by Ozaki et al. reports a hospital mortality of 16/850 (~ 1.9%) patients and a survival of 85% in a mean follow-up of 53.7 (± 28.2) months20. Krane et al. in a cohort of 103 patients, reported a hospital mortality of 0.97% (1/103 patients), the overall survival was 98.1% with a mean follow-up time of 426 ± 270 days (range: 9-889 days). Lida et al. reported a hospital mortality of 2/144 (1.4%) and an overall survival rates of 89.5 and 77.2% at 12 and 60 months, respectively. Oliver et al. reported a hospital mortality of 1/30 patients (3.33%) which was maintained in a 3-month follow-up. Recently, Ngo et al., in a series of 67 patients in Vietnam, reported a 1.7% hospital mortality and a survival of 65/67 (97%) patients at 1 year of follow-up21-23.

The medium-term survival rate in our series is acceptable and comparable with other published cohorts. In 26 patients under 65 years of age, we did not have in-hospital mortality, nor did we have it in the follow-up, 100% of the patients remain alive. These excellent results have also been seen in other series of the same age group24,25.

In our series, we had two patients (5.4%) who presented coronary complications that led to performing CABG in the same surgical act; one of them was the only patient who died. The other patient presented embolism to the circumflex artery confirmed with an angiographic study. Both patients had a bicuspid valve with severe calcification. We assume that greater manipulation of the ring in this technique is a risk factor for presenting this complication, mainly in severely calcified valves. In case of severe calcification along the aortic annulus, Ozaki et al. suggest the use of an ultrasonic surgical aspirator to remove calcium without damaging the annular tissue10. In the report by Ngo et al. two patients (3.3%) were converted to AV replacement surgery due the suspicion that the left coronary leaflet was obstructing the coronary ostium and causing myocardial ischemia. They argue that in the Ozaki procedure, the reconstructed leaflets are at the level of the sinotubular junction, which is higher than the natural one, and believe that a large left coronary leaflet can potentially obstruct the left coronary ostium. When we compare these data with the rate of coronary lesions or occlusions after AV replacement (0.5% to 3%), these are similar23.

HEMODYNAMIC PERFORMANCE

As mentioned above, we observed a significant reduction in the peak and mean gradients of the AV both in the immediate post-operative period and in the follow-up (Fig. 2A and Table 3). In the follow-up, the medians of the peak and mean gradients were 12 mmHg (CI 95% = 10.9-17.7) and 6 mmHg (CI 95% = 5.2-9.2), respectively. Regarding this matter, Krane et al. reported a mean pressure gradient of 8.9 ± 3.8 mmHg at discharge, which remained stable within the 1st post-operative year; Ozaki et al. reported a mean peak gradient of 15.2 ± 6.3 mmHg on average 8 years after surgery. Similar results have been observed in other series10,18,21-23.

This excellent hemodynamic performance is the result of preserving the natural motion of the AV annulus and the coordination of the left ventricle, aortic annulus, sinus of Valsalva, and aorta. This is particularly important in patients with a small AV annulus10,18,26.

FREEDOM FROM REOPERATION AND AORTIC REGURGITATION ≥ II

This is the main point of discussion, the AV reconstruction surgery must still demonstrate long-term durability and to have accurate evidence that we need comparative studies mainly with mechanical prostheses.

Benedetto et al. realized a meta-analytic comparison between series on AV reconstruction surgery and biological prosthesis (Trifecta, Magna Ease, Freedom Solo, Freestyle, Mitroflow, and autograft AV). Meta-analytic estimates showed non-significant difference between AV reconstruction surgery and all but Magna Ease valves with regard to structural valve degeneration, re-intervention, and endocarditis. When compared Magna Ease valve, AV reconstruction and other valve substitutes showed an excess of valve-related events27.

In the follow-up, we have not reoperated any patient for valve dysfunction. Survival free of AV regurgitation ≥ II is 91.9% (Fig. 2A,B).

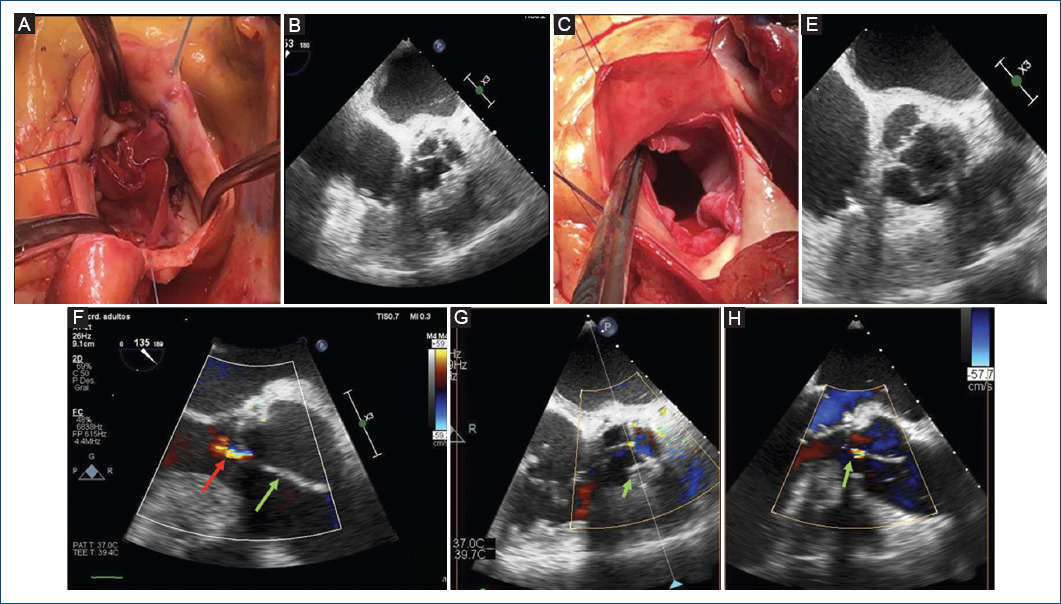

Figure 3 Final results of the neo-AV. A and B: in diastole, we can observe correct coaptation. C and D: in systole, we can observe complete opening. E: TEE, 135°, mild regurgitation (red arrow) and a large coaptation height are observed (green arrow). F and G: TEE X-plane showing optimal results.

Ozaki et al. reported freedom from death, cumulative incidence of reoperation, and that of recurrent moderate aortic regurgitation or greater was 85.9%, 4.2%, and 7.3%, respectively, after a mean follow-up period of 53.7 ± 28.2 months. Reoperations were performed in 15 patients (0.4% per patient-year), in 13 of which the reoperation was due to infective endocarditis20. Krane et al. reported on four patients undergoing reoperation; two due to early valve regurgitation, one due to endocarditis 6 weeks postoperatively; and one patient due to AV regurgitation 2 years after surgery. Freedom from AV regurgitation ≥ grade II at 12 and 24 months was 98.2% ± 0.02% and 92.1% ± 0.05%, respectively21. Other surgeons report similar results18,22,27.

ORAL ANTICOAGULANT THERAPY

Ten of the thirty-eight (26%) patients in our series received AOC therapy, they have a mechanical MV (our first intention was repair this valves) or chronic AF. The rest of the patients received low doses of aspirin for at least 6 months. None of the patients who underwent AV reconstruction surgery as a single procedure (42%) received AOC therapy. We believe that this is one of the main advantages of this procedure, which is essential in developing countries, as we mentioned previously.

Study limitations

This is a retrospective study showing the initials results from a short series of a single hospital and it may suppose a low statistical power and high risk of random error; however, our study is preliminary and it shows preliminary data analysis describing a novel surgical technique. The follow-up time was short and it was not standardized among participants. However, all data available worldwide are based in case series, we need analytical studies that compare AV reconstruction surgery with valve replacement to have quality scientific evidence.

In our study, data were extracted from medical records; therefore, the patients were treated at a national reference center that has an electronic registry of data and images with a rigorous audit process.

IMPORTANCE OF THIS STUDY

In this study, we present the initial results of our experience with our own sizer system. These results are promising and motivate us to continue developing this technique, in which we believe, is completely reproducible, and is one more weapon in the arsenal for the treatment of AV disease, especially in young patients who do not want anticoagulation therapy.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)