Introduction

The foramen ovale is a communication that connects the right and left atrium in the fetal heart, allowing oxygenated blood to get to the fetal arterial circulation. When the foramen does not close completely, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) is formed1.

The PFO serves as a potential conduit for venous emboli to converge into the left atrium. A thrombus trapped passing through PFO is a very uncommon finding with no more than 200 occurrences reported in the literature.

We report a case of a straddling thrombus in a patient with a PFO that was associated with massive pulmonary embolism (PE) and treated surgically as emergency.

Materials and methods

A 53-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a 5-day history of progressive shortness of breath, asthenia, and shivering. He was seen weeks before at another facility for an incarcerated hernia that was surgically repaired with intestinal resection and ileostomy. Previously to medical discharged at this institution, E. coli was isolated at purulent secretion at surgical suture. He was initially diagnosed with abdominal sepsis which was treated with clindamycin.

Heart rate: 155, Blood pressure 90/50 mmHg, and SatO2: 86% SatO2 recovered: 96% and third and fourth heart sound gallop at physical examination.

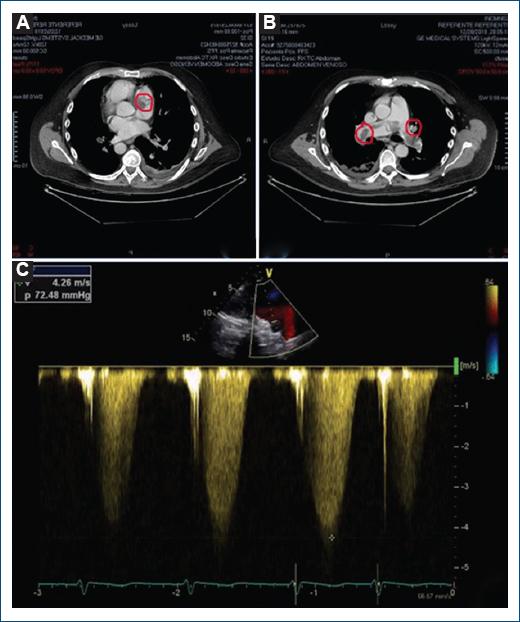

His blood work revealed cardiac enzymes within normal limits (troponin of 0.02 ng/mL). His brain natriuretic peptide was elevated (436 pg/mL). Electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia. Computed tomography angiography of the thorax was done (Fig. 1A), which revealed PE in bilateral main pulmonary artery and segmental arteries involvement also a thrombus at inferior vena cava and right atrium (RA) was informed (Fig. 1B). No signs of deep venous thrombosis were shown on the computed tomography.

Figure 1 A: dilation of the pulmonary artery is observed as well as thrombi in both main branches. B: tricuspid insufficiency. The Doppler velocity signal is 4.6 m/sec and a ventricular-atrial gradient of 72.48 mmhg with an estimated systolic pulmonary pressure of 86 mmhg. C: time-velocity integral of RVOT of 7.6 cm that indates a low right ventricular output.

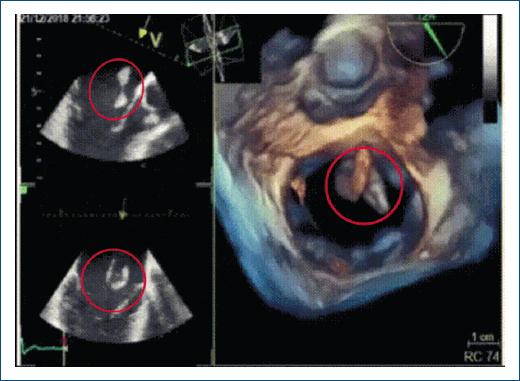

Transthoracic echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular systolic function, moderate concentric hypertrophy, and paradoxical motion of the ventricular septum. The RA and right ventricle (RV) were dilated; this was associated with RV strain and moderately elevated pulmonary systolic pressure. A large serpiginous thrombus in the RA extending to the RV across the tricuspid valve and also an extension of this mass to the mitral valve is shown (Figs. 1C and 2A). Transesophageal echocardiogram showed a large thrombus floating in the RA with a segment being entrapped through a PFO extending to the mitral valve (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 2 A: image of serpenteginous thrombus is observed that crosses the patent foramen ovale and goes to the mitral valve. B: thrombus is observed in the right atrium that enters the right ventricular outflow tract and passes through the patent foramen ovale. C: large thrombotic load is observed in both branches of the pulmonary arteries.

Figure 3 Thrombus displacement by mitral valve. Is observed a wobble of the thrombus in the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve.

A multidisciplinary team decided cardiac thrombectomy (due to high thrombotic burden, situation, and to recent surgical intervention as a contraindication for fibrinolysis) which was performed in addition to the closure of the PFO (Fig. 2B and C), the surgical technique is not described as it is not the purpose of this article.

The patient was transferred to the critical care unit and was discharged after 24 h being intubated, post-surgical fast-track was performed without requirement of inotropes and vasopressors. No complications like migration of thrombi to brain or other part of the body were presented.

Discussion

Our patient clinically presented with abdominal sepsis but has a high probability of PE. We must remember that sepsis, particularly when complicated by hypotension and shock, is considered a risk factor for venous thromboembolism, including upper and lower extremity deep venous thrombosis and PE2,3.

Paradoxical embolism is diagnosed at autopsy or at radiologic imaging when a thrombus that crosses an intracardiac defect is seen in the context of arterial embolic damage in end organs.

Most paradoxical embolisms typically occur at the time of PE, as in our patient, and are likely caused by the increase in right atrial pressure. Paradoxical embolism is uncommon (<2% of arterial embolizations). It is critical to diagnose a right heart thrombus, because it can embolize at any moment.

Recent reports indicate that early mortality rates after surgical embolectomy have improved over the years: in studies conducted by Takahashi et al. reported a 12.5% in-hospital mortality rate for 24 patients undergoing embolectomy4.

The overall mortality rate in patients with RHT has been reported as 28% and as high as 100% in untreated patients5,6.

Greelish et al. recorded low mortality in 15 patients treated with surgical embolectomy compared with 88 patients undergoing medical treatment. Early mortality was fairly similar (surgery 13% vs. medical 17%), but late mortality was lower at follow-up in surgical groups7, as the patient in our clinical case, supporting the decision for surgical intervention over fibrinolysis. Furthermore, thrombolysis was associated with an increased risk of stroke and reintervention at 30 days.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)