Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Convergencia

versão On-line ISSN 2448-5799versão impressa ISSN 1405-1435

Convergencia vol.24 no.74 Toluca Mai./Ago. 2017

https://doi.org/10.29101/crcs.v0i74.4384

Scientific Article

Journalistic infotainment in election coverage. The case of presidential debates

1Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla, México. echevemartin@yahoo.com.mx

Journalistic coverage of elections is increasingly about conflict, scandals, horse race coverage and gaffes, a phenomenon called infotainment, which is detrimental to the political content of elections, this is to say, the candidates’ proposals and leader profiles. To assess the scope of these tendencies in the Mexican press, we focused our research on the coverage of presidential debates in the 2012 campaign, events with profuse political content, and undertook a content analysis of five national newspapers to measure framings related to infotainment (N=209 units). We found that the coverage was focused on the conflict between actors and performance assessment of the event, with little reference to the candidates’ political positions and profiles. Such treatment is detrimental to the potential of civic formation of the debates, a significant feature of democracy.

Key words: infotainment; elections; content analysis; press; debates

La cobertura periodística de las elecciones se centra cada vez más en conflictos, escándalos, acontecimientos chuscos o cobertura de “carrera de caballos”, fenómeno identificado con el término infoentretenimiento, lo que va en detrimento de la sustancia de las elecciones, esto es, las propuestas y perfiles de liderazgo de candidatos. Para determinar el alcance de estas tendencias en la prensa mexicana, tomamos como caso de estudio la cobertura de los debates presidenciales de 2012, eventos ricos en contenido político de gran utilidad cívica, y realizamos un análisis de contenido de cinco periódicos nacionales midiendo los encuadres vinculados con el infoentretenimiento (N=290 notas). Encontramos que la cobertura estuvo centrada en encuadres de conflicto entre actores y de evaluación de desempeño del evento, reproduciendo de manera marginal las posiciones y perfiles de los candidatos. Consecuentemente dicho tratamiento desaprovecha el potencial de formación cívica de los debates, tan significativo para la democracia.

Palabras clave: infoentretenimiento; elecciones; análisis de contenido; prensa; debates

Introduction

A controversial tendency, the proliferation of media formats and messages that mix information on political events with entertainment elements, called infotainment, has been object of numerous criticisms regarding the potential effect of the de-politization of the audiences. It has been empirically demonstrated that the trivialization of politics by emphasizing contents linked to scandals, conflicts and stratagems of the politicians, in detriment to the political problems and campaign proposals, in addition to impoverish the voters’ awareness of what is at stake in the election, has the consequence of fostering mistrust, cynicism —understood as an a priori judgment on the petty intentions of the politicians —and the little involvement of voters with the candidates, the political system or the very democratic system (Patterson, 1993; Capella and Jamieson, 1997; Moy et al., 2005).

In parallel to its effects, clearly distinguishable is the infotainment’s capacity to colonize various spaces of the political arena: the figure of the presidential candidate that reveals aspects of their intimate life in game shows or the agonal, dramatic or sportive treatment of legislative or juridical processes, formerly solemn is not unusual any more. Events with content relevant to understand the political processes are codified in the key of entertainment, thinning its substance by means of treatments that provide utterly different representations from the original event.

This might be the case of television debates and the journalistic coverage they receive. They are events rich in political information, which allow assessing the politicians’ profile, the comprehension of problems, the suitability of their proposals, at least in terms of their performance as communicators; the characteristics of infotainment reported in the literature might translate these characteristics into contents centered on confrontation, personalist banality or scandal, wasting the chance to amplify the scope of a highly democratic exercise.

The research hereby presented has as an end to verify the reach of infotainment in the journalistic coverage of presidential debates in the 2012 Mexican election, as a case study regarding the coverage of electoral campaigns in general, and at the same time identify the elements that characterize it. Likewise, it is intended to verify if it is rather a homogeneous tendency and so dominant regarding the newspapers in which it is featured, the actors addressed and the coverage time, or else it is a selective phenomena that occurs in relation to various stages, actors and publications involved in the electoral coverage.

The analysis of the content produced for such end —from out of 290 items from five national newspapers and published the days after the debates— identifies the presence of infotainment by looking for a series of framings related to the thematic and stylistic characteristics of such phenomenon. The final results indicate the prevalence of such framings in coverage, even though there is important heterogeneity in they way they manifest.

The television debate as a theoretical object; conceptualization, democratic potential and media representation framings

As an exercise of performance assessment, the present work establishes a theoretical strategy that contrasts the phenomenon of television debate, its communicative nature, normative suppositions and empirical consequences with the patterns of journalistic treatment which it is subject to. The contrast between the factual object and its journalistic representation overcomes a per se media description and it is possible to make more accurate observations of the latter’s behavior.

Object, regulation and effects of television debates

As an object of study, television debates are conceived as arenas or interaction situations with a ritual character, in which the political discourses are publicly compared, disseminated and assessed under specific rules by actors who try to influence the behavior of voters, by means of staged strategies of self-presentation. In this framework, political conflict is formalized, structured, controlled and channeled, albeit within the limits of civility (Bélanger, 1998; Gosselin, 1998; Kraus and Davis, 1981). The debate is thus conceived as a model at small scale of the democracy thought as an institutional framework for the treatment of conflicts from communication and dialogue (Dader, 1998).

This specific conceptualization has implications regarding the way in which the media decide to report the event, since it entails the public staging of a political confrontation subject to rules of common courtesy and ordered dialogue (an aspect we will address later).

In a reading at the level of political system, the mere organization of the debates and their amplification by the media have per se democratic implications that are understood as a contribution to the quality of the votes cast by the electorate: voters are provided with the same electoral information, which places them at an equal position (Benoit and Sheafer, 2006); there is more direct and prolonged contact between voters and candidates, without the mediation of an editorial, prone to bias (Benoit and Brazeal, 2002). The regular tendency of the voters to selectively expose themselves to the messages of the preferred candidates is broken by the comparative and simultaneous exposure of the candidates, in such manner that they forcefully learn the proposals of the non-preferred candidates and sharpen or rationalize the contrasts between the candidates.

Likewise, the political information there exposed reaches, via the debates, high audience levels, virtually impossible to reach for other formats of political communication, as well as an extensive and relatively prolonged media coverage before and after the event, which makes it very likely that debates grab the attention of scantly-politicized citizens attentive to the campaigns, who acquire the minimal knowledge to cast a vote (McKinney and Carlin, 2004).

The empirical research on the effects of the debates verifies, on the one side the series of behavioral effects moderated in the voters, i.e., increasing their motivation to vote, look for more information on the campaign and intensify the discussion with peers (Wyatt, 2000); however, the main effect of such events lies increasing the voters’ knowledge on what at stake in the campaign. The average duration of two hours implies a prolonged exposition to a large amount, relatively sophisticated, of information by means of which the citizens are informed about public problems, the specific topics and stance of each candidate and are, in consequence, in better conditions to assess them (Benoit et al., 1998; Cho, 2009; Drew and Weaver, 2006; Jarman, 2005).

This way, through the “direct” reading of the candidates’ personal unfolding, the voters obtain a more complex impression of their character and stance in the contest so that they assess the candidates with better elements and in the end they modify or change their perception of the candidates (Cho, 2009; Jarman, 2005).

In a space in the media dominated by the formats of political communication increasingly poor such as newscasts or spots (Juárez and Echeverría, 2009), television debates can be characterized from the normative standpoint as information sources and institutions with important potential to produce rationality, deliberation and informed electoral decision, contributing this way to increase the quality of democratic processes.

Infotainment treatment of television debates; framings and empirical evidence of coverage

The journalistic coverage of television debates is doubly relevant: in the first place, it is a device that draws people who did not witness the debate; and secondly, it may make the voters who watched the debate reinterpret it in different ways (Benoit and Currie, 2001). Hypothetically, a public-service normative orientation would make all the information media cover the debate in such manner that it allowed quantitatively amplify, in terms of audience, reaching several advantageous suppositions and effects previously listed, regarding the principles related to the civic function of journalism, its (normative) purpose of making social reality understandable (McQuail, 1998).

However, in recent years the phenomenon of infotainment1 has become relevant as a pattern of journalist treatment of political occurrences. For this work’s purposes and before a still-too-broad definition of the term —for it involves various topics, styles and formats in a myriad of channels of public communication—, we define its specificity as regards political journalism, clarifying the aspects associated with the phenomenon both at macro, particularly economic, and micro levels in the journalistic messages, which will be useful to reach a reasoned conceptualization.

With regard to the macro dimension of the phenomenon, it is evident the propensity of journalistic enterprises to reach broader audience markets than their traditional elite audience, already predisposed to consume political information. In based on this, on the one side they endeavor to produce messages that basically pursue to capture, captivate and retain the attention of audiences by means of emphasis on the stylistic, attracting and emotive aspects of the messages; this is functional for the mercantile interests of the media, since attention is the fundamental (and scarce) asset the media sell their advertisers (McQuail, 2001).

On the other, they do what Gans calls a “popularization” of journalistic information; this is, “the adaption of a cultural product initially created for a tasteful culture” (in this case, the reference press with substantial political information) “to the consumption and use of a culture corresponding to an audience with lower status that the original” (Gans, 2009: 19).

Usually such adaption fundamentally involves an operation of content simplification, which is ensued by other stylistic alterations such as replacing technical language with colloquial, or abstract images or forms with natural or popular. This way, the media formerly aimed to audiences of high cultural level popularize the news, including the political, admitting codes of popular culture which are commonly close to entertainment.

In its micro level, related to the messages’ characteristics, this phenomenon can be understood as the elaboration of political news under a media logic, an “evocative, encapsulated, highly thematic, familiar with audiences and easy to use” grammar (Altheide, 2004: 294 ), which prescribes the structure of messages with fragmentary language and rhythm, simplified and gimmicky to communicate with the audiences. For its part, such grammar establishes “the codes (which journalists use) to define, select, organize and recognize information” (Altheide, 2004: 294), in such manner that it almost fully structures the process of news production.

We can summarize what we have said so far conceptualizing political infotainment as an operation of emphasis on the news of the political activity, of formal elements, stylistic or thematic capable of making political contents more accessible and attractive for audiences initially not interested or familiarized with politics; such emphasis uses a set of simplifying, fragmenting and gimmicky codes which in the base of the process of news production define, select, organize and present news likely to entertain, the main strategy to grasp and grip the audiences’ attention.

Well now, an adequate manner to categorize the journalists expressions related to infotainment is by means of the theoretic-methodological resource of framing2, as it helps describe what the treatment consists in. Regarding the election coverage, international literature reports on the one side, the prevalence of a traditional thematic macro framing, centered on the substance of politics and oriented to the democratic performance of the media; this refers to problems and solutions of public policy, discussion of public topics (causes, solutions and measures), the politicians’ stances on these problems, descriptions of legislations or governmental programs and their implications (Berganza, 2008; Brants and Neijens, 1998; Lawrence, 2000).

Conversely, the growing presence of a macro framing of contest is underscored, which for the present theorization is the clear expression of infotainment. It is a way to understand and explain politics as a confrontation, in which politicians compete for advantages and are interested in winning (Jensen, 2012). This general framing is broken down in at least five particular framings —conflict, strategy, game, dramatization and personalization—, which specify the topic and stylistically the framing itself.

The framing of the conflict characterizes politics as a polarized scenario, in which there are frictions and controversies between individuals (in solitary), groups and institutions, with little attention to topics at stake and their very own substance. Close to such framing is the strategic, in which journalist interpret the “real” motives and intentions that underlay the actions or proposals of the actors, as well as the necessary tactics for these to win positions.

For their part, the game framing introduces the use of language and sports narrations as main characteristics, this way it shares the attributes of a ferocious contest with the previous; an agonal and confrontational character. This is commonly expressed with the metaphor of the “horse race”, in virtue of which the leaders in the “race” to reach the finish line are reported resorting to surveys (Anikin, 2009; Jensen, 2012; Johnson-Cartee, 2005).

The dramatic framing, for its part, includes human interest stories that express the “human face” and “emotional angles” of the events, topics or problems related to the campaign, as well as funny occurrences of the candidates; this is the sphere of the personalization phenomenon, in the dual meaning of emphasis on characters and life stories that generate an identification with the audience, or else the characterization of politicians as individuals, with personal attributions and private lives even before being representatives of collective interests.

The implementation of these contests framings turns the infotainment tendency into schemas of journalistic production and contents, against the traditional political framing, as it intends to communicate the exciting and entertaining dimension of the political processes instead of the substance of what is a stake. In the case of debates, a coverage that deems news items about them as entertainment attenuates the advantages mentioned in the previous section, disfavoring its important civil function.

Truth is that candidates have uttered a number of scandalous revelations and invectives over the only eight debates held in the last four presidential elections in Mexico; which have been studied by linguistic cognitive disciplines. Albeit, the panoramic content analyses in this regard find that considering debates as a set, confrontation is lesser: for example, the functional analysis of the 2006 debates states that on average there were 6.21 exclamations (public policy proposals) per 2.08 attacks (Téllez et al., 2010). Another work finds that the proportion of enunciations referring proposals in the two debates was five times larger than attacks (Echeverría and Chong, 2013). By and large, the empirical analyses of the debates verify these have been carried out to a good extent with civility.

However, another work shows that the news items published the day after the debates in 2012 in the reference newspapers indicate a similar proportion of proposals and attacks (Echeverría and Millet, 2013), this way the newspapers conveyed the impression of a debate —in the terms here exposed— half substantial, half confrontational. Such representation smears its civic performance with everything it entails. The replication of these findings extending the scope of analysis to the national coverage of the debate is the end of the following empirical exercise.

Methodology

This work’s methodological strategy has as an end to verify the degree of penetration a infotainment coverage in the national press, by means of content analysis applied to the coverage of highly visible politically significant events such as the television debates, which on their own have considerable thematic substance, even though the sporadic manifestation of confrontations and its nature of structured verbal conflict make them prone to be framed into the contest schema, symbolic concretion of the infotainment tendencies. This way, the debate is configured as an ideal case study for the aforementioned end.

Beyond its qualitative weight on public opinion and accessibility regarding historic archive, the election of the press deemed “serious” or “generalist”, by opposition to the “sensationalist”, or tabloids, also lies in the fact that apparently it is the least porous medium to infotainment tendencies, unlike television in which these have been persistently present for several years. The penetration of such tendencies in the reference press would be a highly significant indicator of the reach of the phenomenon in the Mexican media system.

Our sample consisted in an analysis of the digital archive of newspapers: Reforma, La Jornada, El Universal, La Crónica, Milenio and Excélsior; which were selected as they are newspapers with large circulation prints, considered “serious press”, prestigious, according to Padrón Nacional de Medios Impresos de la Secretaría de Gobernación mexicana (SEGOB, 2013). All the coverage generated by each debate over subsequent days was revised; nine days in the case of the first debate (from 7th to 15th May) and five for the second (from 10th to 14th June). The items were selected according to their reporting or judging of the debate events or else if they discussed any aspect of their performance or consequences, reaching 290 items.

Regarding the book of codes, the one developed for the analysis of the 2012 presidential election coverage (Echeverría and Meyer 2015), which was built inductively combining a constant comparison qualitative analysis and the definition of framings reported by international literature (Alberg et al., 2011; Capella and Jamieson, 1997; Klein, 2000; Lawrence, 2000; Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000; Strömbäck and Luengo, 2008).

From such exercise the macro or general framings (for this research they were called “contest” and “political”) emerged, were verified and adjusted, plus six particular framings (“drama”, “game” and “strategy”, corresponding to the first macro-framing, and “political topics and ideas”, “political process” and “political leadership” 3 for the second) as well as 23 sub-framings, from these six. The Kappa reliability for such protocol was fixed at .831 for macro-framings, and .739 for framings, considered acceptable for an exploratory exercise such as the present (albeit the framings did not reach a satisfactory reliability parameter).

The criterion of a single dominant framing by item was adopted. Although in the literature it is admitted there may be several framings in an item, dividing the content so finely would imply the identification of multiple framings which would make the global observation difficult (Binderkrantz and GreenPedersen, 2009). For its part, the analysis unit in the item was the heading, owing to practical reasons, but also on theoretical grounds, since this is the most powerful device to frame the item (Van Dijk, 1990), capable of activating concepts in the reader ands thus influence the rest of the reading of the item (Klein, 2000; Tewksbury et al., 2000).

For their part, the 2012 campaign debates were held between the candidates Enrique Peña Nieto from Partido Revolucionario Institucional, former governor of the State of Mexico, Josefina Vázquez Mota from Partido Acción Nacional, former secretary of Social Development and Education and federal representative, Andrés Manuel López Obrador from Partido de la Revolución Democrática, former mayor of Mexico City and previously presidential candidate, as well as Gabriel Quadri de la Torre from Nueva Alianza, functionary, consultant and environmentalist entrepreneur. The first debate was held on May 6th, and broadcast by channels 5 (Televisa) and 40 (TV Azteca) (which does not have national coverage), attaining a 10.4 rating points audience in the first company (Torres, 2012).

The second presidential debate was broadcast on June 10 on channels 2 (Televisa) and 13 (TV Azteca), which together with other license-holders and dealers reached a potential coverage of 92.5% of the households at national level. Combining with this the coming elections, the audience of such event was 22.6 rating points, the highest in history for a presidential debate (Torres, 2012). According to surveys, 60% of the citizens watched the debate live or as a repetition and conversed about it (Torres, 2012), while for 55% of the viewers it was important that all debates had been televised (Flores-Villar, 2012).

Findings

The results of content analyses in the first place expose differences regarding the coverage volume given to each debate, the dominant framings in the coverage, the specific aspects in which they are prevailing, in terms of actors and moments, and the degree of homogeneity of these tendencies in the sample newspapers.

A first finding refers the differenced duration of the coverage between the first and second debates, it reveals the dynamic of the topics regarding the emphasis given by the newspapers, regardless of the event itself. In this respect, the contrast between both debates is very significant. Even if both coverages are extensive the next and coming days after the event, they later decrease and gradually fade —a typical treatment—, the first debate reproduces 82 items the first day, 81 the second, in a total coverage of 9 days (19, 17, 11, 7, 3, 6 and 3 items each day after the first); while the second debate generates 46 items the day after, 12 the next, in a 4-day coverage, with only two and one item in the third and fourth days.

The general observation is that despite both debates concentrate slightly more than two thirds of the items in the first and second day, to later fade and disappear, the second one has little visibility and disappears faster in the media. This particularity will be stressed when interpreting the data in relation to the rating levels of both events.

As regards the framings, in global terms the contest macro-framing doubles in frequency (66%) the political framing (33%) (see table 1 4). It is noticeable that both the topics (3%) and leadership (1%) framings are scantly visible. Conversely, the framing of political process seizes a third of the items (29%); particularly, distinguishable is the sub-framing “organization, procedures and formal regulation” with about a quarter of them (23%); this is mainly positive or negative assessments on the organization and performance of the debate, transmission coverage, as well as the corrective measures for the coming second debate by electoral authorities, political actors and distinguished members of civil society.

As regards the contest macro-framing, which operationalizes infotainment, the most frequent is the strategy framing (32%) in virtue of the conflict sub-framings, both inside, between formal actors (20%), and outside the political arena, between civil society actors (6%).

Secondly, outstanding is the game framing (23%) with characterizations of the debate in terms of winning and losing (9%), of sports, war and competence (6%) or else scores (7%), this is to say, expressions from the public opinion as measures in real time of the debate, poll surveys, focal groups or collective conversation in the virtual social networks, stressing to reveal who “won” or “lost” the debates.

Finally, the drama framing is not recurrent (10%) and distinguishes the funny event of the aide in the first debate (8%), whose attire in combination with her background modeling for gentlemen’s magazines stirred vehement reactions in the media coverage.

There exist, on the other side, important discrepancies in the framings emphasized in debates possibly in function of the difference in coverage of them, since the first received almost four times more coverage than the second.

The second debate was much more centered on the contest framing than politics (82% and 12% in contests, and 38% and 62% in politics). This focused less on the assessment of the format of the debate, an aspect that changed from 28% in the first debate to 3% in the second. The sub-framing of conflict increased almost to 40% of the coverage, by contrast with 21% in the first debate. The framing of game also increases, a fifth (21%) in the first to a third in the second (31%), in particular regarding the use of scores (from 6 to 13%) and a language of sports, war or competence (from 5% to 9%). To sum up, possibly from a lower coverage, the second debate significantly focused on infotainment framings.

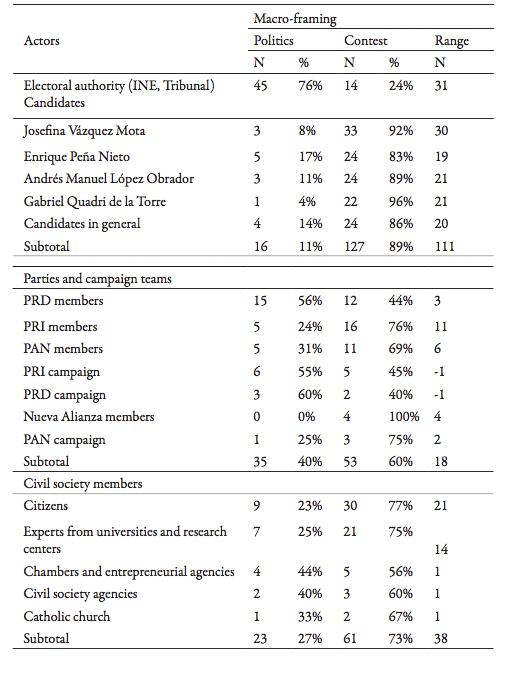

The following research objective consisted in enquiring the extent to which framings are applied to the general coverage, which makes their application homogenous, or else centered on certain elements such as times and actors, which makes it selective. This last is answered by means of table 2, which out of parsimony associates only the political and contest macro-framings with the actors. Using the parameter of range, we notice that various sorts of actors are rather associated with one framing or the other. The party actors (members of political parties from various hierarchies, as well as campaign teams) present better balance between the contest and political framings. Save the members and campaign team of PAN and PRI, whose items are mainly produced with the contest macro-framing, the rest of these actors exhibits balance between them (R=18).

The group of civil society actors is more imbalanced than the previous (R=38). Particularly abundant are the citizens’ perceptions via surveys, as well as opinions of experts, whose discourses are framed as winning or losing expressions, not as technical assessments; this way, this group exhibits imbalance in favor of the contest macro-framing, which is triple the size of politics (73 and 27%, respectively).

In the political actors, there is disproportionate imbalance between the macro-framing of politics (11%) and contest (89%) (R=111). The proportion and range are similar for the various actors, nevertheless it slightly increases in the case of Vásquez Mota and Quadri de la Torre (32 and 36% of the contest macro-framing, respectively).

By contrast, the electoral authority, which comprises Instituto Federal Electoral, its councilors and the electoral tribunal, is mainly framed within political processes in 76%, before 24% in the key of contest.

In function of these data it is possible to state that the application of a framing heavily depends on the sort of actor, this is to say, it is selective. A statistical correlation test applied to the variables of actor and macro-framing, c2 (3, N=290) = 74.77, p=.000, verifies this tenet, which besides appears in a very significant magnitude (Cramer’s V, .509). However, inside these groups the pattern is more homogeneous in the case of candidates, whose events are framed in a disproportionate manner more as a contest than a political election.

The unfolding of framings over time and, therefore, their distribution become another dimension of emphasis conferred to them: even if simple frequencies establish an implicit hierarchy, it is also significant if this or that framing was sustained over the coverage or else if it was intensively used for some days to later disappear. In order to clarify this indicator, we take the four most frequent sub-framings into account, “organization, and formal regulation”, which corresponds to the framing of process, as well as “conflict”, “expressions of winning or losing” and “public opinion scores”, corresponding to the macro-framing of contest and we unfolded over time (see graph 1).

The general observation is that the visibility of the various framings differs over time. The three contest framings have a very emphatic display over the two days after the debate, but they dramatically decrease from the second to the third day and quickly disappear. The framing of “organization and formal processes” around the debate, in the first day makes room for items of contest, but recovers impulse by the second day and gradually sustains over the three following days to wane after the fourth.

The coverage of the second debate has a different behavior, given its unfolding in short time, the reduced frequency of political framings and the prevalence of contest framings that have the same behavior as in the first debate. For example, the conflict framing is the most frequent with 17 items the first day, but it dramatically reduces on the second day with five items. The same occurs for the score sub-framing, which changes from seven items to one the next day. This means that the first characterization of the debate by the media is that of a contest, but later it focuses on its nature of political process, even for a relatively prolonged time.

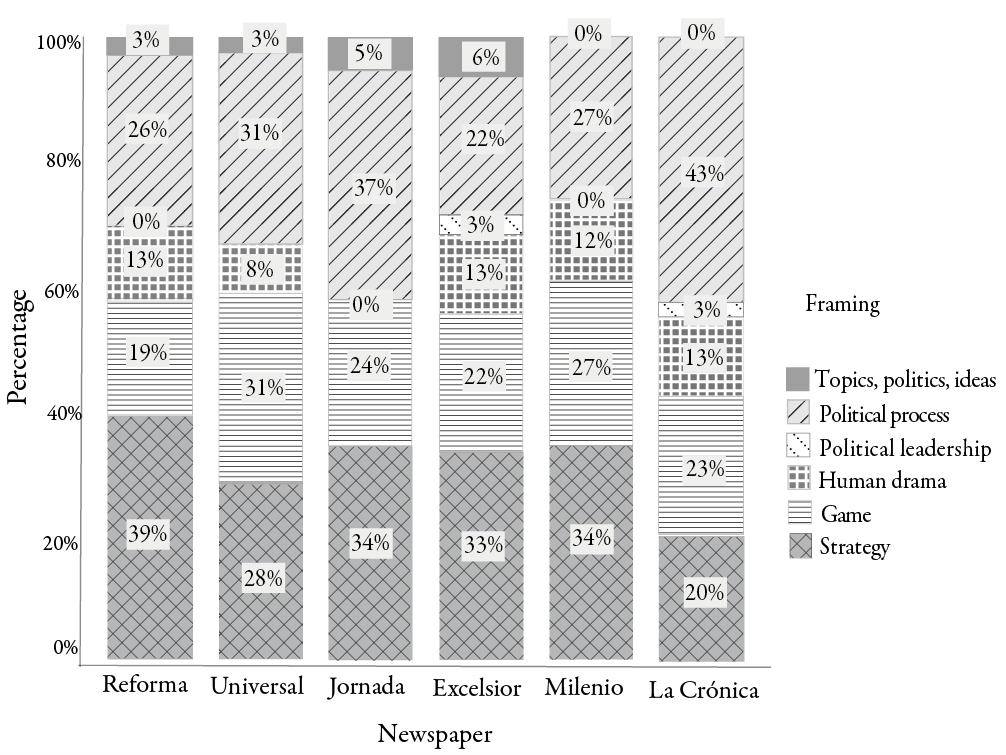

Finally, we wonder to what extent the application of framings is a homogeneous tendency in the newspapers so that it may become a full attribution of the reference Mexican press. As we noticed in graph 2, there are differences in the treatment the various newspapers give to debates, even though they do not seem significant. No newspaper gives important space to the topics and problems of the debate or expresses on the candidates’ leadership. The proclivity to drama (personalization, funny events, etc.) has variations, however its prevalence is in the range from 8 to 13%, with the exception of La Jornada, which does not have an item with this approach.

The framings of political process, game and strategy prevail in all the newspapers and have a similar proportion among them, even though emphases are different. For example, La Crónica frames 43% of its items as a political process, while Excélsior does only in 22% of its items. In like manner, Reforma gives 19% of its items a game framing, while El Universal does in 31% of the items. To sum up, and verifying data with Chi-squared test, c (25, N=290) = 25.58, p=.43, there does not seem to be a general relation between the media and the debate framings; this is, there exists a heterogeneous treatment of the event and on occasion almost idiosyncratic.

Discussion and conclusions

As a study case, the journalistic coverage of presidential debates serves as a relevant indicator of the journalistic leanings in the treatment of political reality. The data exposed allow satisfying the main enquiry about the presence and scope of the infotainment framings in the election coverage.

In the first place, the significant relevance between the coverage volume of the first and second debate is stressed, in contrast with their rating levels, which for the second debate were much higher. We here verified the way in which the news-becoming value of the first debate, a “great media event” eagerly expected by politicians and citizens, turns the comparable relevance of both in favor of only one.

Regarding the results of the measuring of framings, the debate seems to be more important for the press because of the excitement it may stir or its per se sociopolitical relevance, without paying attention to the political content displayed there. This is supported owing to the processual and strategy framings emphasized: by framing nearly a quarter of the items as events centered on the organization, proceedings and regulation of the debate, the characterization of the debate as a significant “media event” due to its massive nature and institutional relevance is evinced.

On the side of the contest framing, it seems that the nature of the debate as a regulated verbal conflict is used by the press to emphasize the conflict or clashes, which indeed occurred there, though sporadically, or else its reading in terms of political stances in “the race for the presidency”, the two most recurrent sub-framings. Adding to the funny event of the aide in the first debate, not only did the contest framing in general double the thematic in frequency, by means of which the debate turns into an individualist confrontation for power in the press, but also the aspects regarding topics, policies and ideas are virtually invisiblized, as well as the candidates’ political leadership, elements of political substance that promote the most learning from the debates in the audiences, according to the literature.

The preference for the debates’ contest framing is very well illustrated in its coverage time: the days immediately after them, where there is greater expectations about the journalistic coverage record a dominant presence of items with this framing. Over the following days, when attention to the debate dilutes is when the thematic framing is stressed —particularly the official assessment of the process— and the contest framings are promptly de-emphasized. Adding to their net high frequency, the intension of giving it greater visibility to the infotainment treatment of the framings is verified, publishing at the times with the most readers.

By detailing the nature of the framings, it is found that those linked to infotainment are the most clearly applied on the candidates, protagonists of the election as a contest, and the citizens, as referees entitled to produce a verdict of “victory” or “defeat”. The electoral authorities are partially distanced from such characterization, as they are the spokespersons of the debate as an official and legal event, as well as the partisan actors as managers or partners in its organization.

Furthermore, the tendency of infotainment is homogeneous in the newspapers regarding the emphasis each makes on certain framings. What they share is the marginal reproduction of the campaign topics and leadership profiles, substantial aspects of the debates, as well as important attention to the debate as an official political process and as a spectacular conflict.

These three data point at a heterogeneous tendency of infotainment to penetrate in the election coverage, at least regarding televised debates. The contest framings are emphasized at certain times and linked to certain actors and underscored at varying degrees by certain newspapers, with which the hypothesis of the general and overwhelming penetration of this treatment is discarded.

Such behavior might link to a newspapers’ tension between public service vocation, which points at reproducing and so magnifying the thematic substance of the debates, and commercial pressure, which identifies the opportunity to reach a depoliticized market, which maybe did not watch the debate but might be interested in reading the papers to find out about it, given the great expectation it generates, as long as the information has infotainment treatment capable of grasping their attention.

In conclusion and heading toward a performance assessment, the journalistic coverage of the debates does not amplify the knowledge displayed in them, while regarding the topic at stake in the election or the candidates’ profile increases, instead of shortening, the distance between the knowledge of those who watched the debates and those exposed to it by means of their coverage, and to sum up, its does not contribute to the rationality and deliberation they enable.

REFERENCES

Alberg, Toril et al. (2011), “The framing of politics as a strategy and game: a review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings”, en Journalism, núm. 2, vol. 13, Estados Unidos: Sage. [ Links ]

Altheide, David (2004), "Media logic and political communication”, en Political Communication, núm. 3, vol . 21, Estados Unidos: Routledge. [ Links ]

Anikin, Evgeny (2009), "The 2008 US presidential election in the mirror of sports metaphor (in the French Press)”, en Respectus Philologicus, núm. 27, vol. 1, Polonia: Vilnius University. [ Links ]

Aruguete, Natalia (2013), "La narración del espectáculo político: pensar la relación entre sistema de medios y poder político", en Austral Comunicación, núm. 2, vol. 2, Argentina: Universidad Austral. [ Links ]

Baym, Geoffrey (2008), "Infotainment”, en Donsbach, Wolfgang [comp. ], The International Encyclopedia of Communication, Inglaterra: Blackwell Publishing, [ Links ]

Bélanger, Yré (1998), "La comunicación política, o el juego del teatro y de las arenas", en Gilles, Gauthier, Yré, Gosselin y Jean Mouchon [comps. ], Comunicación y política, España: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Benoit, William y Currie, Heather (2001), "Inaccuracies in media coverage of the 1996 and 2000 presidential debates”, en Argumentation and Advocacy, núm. 38, Estados Unidos: American Forensic Association. [ Links ]

Benoit, William et al. (1998), "Effects of presidential debate watching and ideology on attitudes and knowledge", Argumentation and Advocacy, año 34, núm. 4, Estados Unidos: American Forensic Association . [ Links ]

Benoit, William y Brazeal, LeAnn (2002), "A functional analysis of the 1988 Bush-Dukakis presidential debates”, en Argumentation and Advocacy, núm. 4, vol. 38, Estados Unidos: American Forensic Association . [ Links ]

Benoit, William y Sheafer, Tamir (2006), "Functional theory and political discourse: televised debates in Israel and the United States", en Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, núm. 2, vol. 83, Estados Unidos: Sage . [ Links ]

Berganza, María-Rosa (2008), "Medios de comunicación, espiral del cinismo y desconfianza política. Estudio de caso de la cobertura mediática de los comicios electorales europeos", en Zer, núm. 25, vol. 13, España: Universidad del País Vasco. [ Links ]

Berrocal, Salomé et al. (2012), "Una aproximación al estudio del infoentretenimiento en Internet: origen, desarrollo y perspectivas futuras", en adComunica. Revista de Estrategias, Tendencias e Innovación en Comunicación, núm. 4, España: Facultat de Ciències Humanes i Socials, Universitat Jaume I. [ Links ]

Binderkrantz, Anne y Green-Pedersen, Christoffer (2009), "Policy or processes in focus?", en The International Journal of Press/Politics, vol. 14, núm. 2, Estados Unidos: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Brants, Kees y Neijens, Peter (1998), "The Infotainment of Politics", en Political Communication, núm. 2, vol. 15, Estados Unidos: Routledge . [ Links ]

Capella, Joseph y Jamieson, Kathleen (1997), Spiral of cynicism: the press and the public good, Inglaterra: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Cho, J. (2009), "Disentangling media effects from debate effects: the presentation mode of televised debates and viewer decision making”, en Journalism and Mass Communication Quaterly, núm. 2, vol. 86, Estados Unidos: Sage . [ Links ]

Dader, Jose-Luis (1998), Tratado de comunicación política, España: Edición propia. [ Links ]

Debray, Regis (1993), L´État séducteur, Les révolutions mediologiques du pouvoir, París: Editions Gallimard. [ Links ]

Drew, Dan y Weaver, David (2006), "Voter learning in the 2004 presidential election: did the media matter?", en Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, núm. 1, vol. 83, Estados Unidos: Sage . [ Links ]

Echeverría, Martín y Meyer, José (2015), "El infoentretenimiento en la cobertura periodística de las elecciones. Un abordaje desde la teoría del encuadre", en Daniel Ivoskus, Angélica Mendieta y Raffaeli Marina [comps. ], Sexto sentido para gobernar. Política y comunicación, México: BUAP, Paralelo Cero. [ Links ]

Echeverría, Martín y Chong, Blanca (2013), "Debates presidenciales y calidad de la democracia. Análisis empírico normativo de los debates mexicanos de 2012", en Palabra Clave, núm. 2, vol. 16, Colombia: Universidad de La Sabana. [ Links ]

Echeverría, Martín y Millet, Ana (2013), "El infoentretenimiento en campaña. El caso de los debates presidenciales de 2012", en Carlos Vidal [comp. ], XX Anuario de la Comunicación CONEICC, México: CONEICC. [ Links ]

Edelman, Murray (1991), La construcción del espectáculo político, Argentina: Manantial. [ Links ]

Flores-Villar, Alberto (2012), "¿Cuánto influyó la TV en el voto?: caleidoscopio electoral", en Animal Político. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://www.animalpolitico.com/2012/07/cuanto-influyo-la-tv-en-el-voto-caleidoscopio-electoral/ [7 de julio de 2012 ]. [ Links ]

Gans, Herbert (2009), “Can popularization help the news media?”, en Barbie Zelizer, The changing faces of journalism. Tabloidization, technology and truthiness, Estados Unidos: Routledge . [ Links ]

Gosselin, Yré (1998), "La comunicación política, cartografía de un campo de investigación y actividades", en Gilles Gauthier, André Gosselin y Jean Mouchon, Comunicación y política , España: Gedisa. [ Links ]

Igartua, Juan et al. (2007), “El tratamiento informativo de la inmigración en los medios de comunicación españoles. Un análisis de contenido desde la Teoría del Framing”, en Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, núm. 13, España: Universidad Complutense de Madrid. [ Links ]

Jarman, John (2005), "Political affiliation and presidential debates. A real-time analysis of the effect of the arguments used in the presidential debates", en American Behavioral Scientist, núm. 2, vol. 49, Estados Unidos: Sage . [ Links ]

Jensen, Lars (2012), "Politics as a Game in Danish Newspapers", en Sonderborg papers in linguistics and communication, núm. 2, Dinamarca: University of Southern Denmark. [ Links ]

Johnson-Cartee, Karen (2005), News Narratives and News Framing. Constructing Political Reality, Reino Unido: Rowman and Littlefield. [ Links ]

Juárez, Julio y Echeverría, Martín (2009), "Cuando la negatividad llega a lo local: publicidad política en tres elecciones estatales en México", en Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, vol. 12, núm. 64, Estados Unidos: Universidad de La Laguna. [ Links ]

Klein, Ulrike (2000), "Tabloidized political coverage in the german Bild-Zeitung”, en Colin Sparks y John Tulloch [comps. ], Tabloid Tales. Global Debates over Media Standards, Estados Unidos: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. [ Links ]

Kraus, Sydney y Davis, Daniel (1981), "Political debates”, en DanNimmo y KeithSanders [comps. ], Handbook of Political Communication, Inglaterra: Sage. [ Links ]

Lawrence, Regina (2000), "Game-Framing the issues: tracking the strategy frame in public policy news", en Political Communication, núm. 17, Estados Unidos: Routledge . [ Links ]

McKinney, Mitchell y Carlin, Diana (2004), "Political campaign debates”, en Lynda Kaid [comp. ], Handbook of Political Communication Research, Estados Unidos: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

McQuail, Dennis (1998), La acción de los medios, Argentina: Amorrortu. [ Links ]

McQuail, Dennis (2001), Introducción a la teoría de la comunicación de masas, España: Paidós. [ Links ]

Muñiz, Carlos (2011), “Encuadres noticiosos sobre migración en la prensa digital mexicana. Un análisis de contenido exploratorio desde la teoría del framing”, en Convergencia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, núm. 55, vol. 18, México: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. [ Links ]

Moy, Patricia et al. (2005), “Communication and Citizenship: Mapping the Political Effects of Infotainment”, en Mass Communication and Society, núm. 2, vol. 8, Inglaterra: Routledge. [ Links ]

Patterson, Thomas (1993), Out of Order, Estados Unidos: Vintage. [ Links ]

Reese, Stephen, (2010), “Finding Frames in a Web of Culture. The Case of the War on Terror”, en D´Angelo, Paul y Kuypers, Jim [comps. ], Doing news framing analysis. Empirical and theoretical perspectives, Estados Unidos: Taylor & Francis. [ Links ]

Sádaba, Teresa et al. (2007), "Propuesta de sistematización de la teoría del framing para el estudio y praxis de la comunicación política", en Observatorio (OBS), núm. 2, vol. 6, Portugal: Editora Mundos Sociais. [ Links ]

SEGOB (2013), Padrón Nacional de medios impresos, México: Secretaría de Gobernación. [ Links ]

Semetko, Holli y Valkenburg, Patti (2000), "Framing European politics: a content analysis of press and television news", en Journal of Communication, núm. 1, Estados Unidos: Wiley. [ Links ]

Serpa, Marcelo (2013), Eleições espetaculares: como Hugo Chávez conquistou a Venezuela, Brasil: Contra Capa, Faperj. [ Links ]

Strömbäck, Jesper y Luengo, Óscar (2008), “Polarized pluralist and democratic corporatist models. A comparison of election news coverage in Spain and Sweden", en The International Communication Gazette, núm. 6, vol. 70, Estados Unidos: Sage . [ Links ]

Téllez, Nilsa et al. (2010), "Función discursiva en los debates televisados. Un estudio transcultural de los debates políticos en México, España y Estados Unidos", en Palabra Clave 13, núm. 2, Colombia: Universidad Javeriana. [ Links ]

Tewksbury, David et al. (2000), "The interaction of news and advocate frames: manipulating audience perceptions of a local public policy issue", en Journalism y Mass Communication Quarterly, núm. 4, vol. 77, Estados Unidos: Sage . [ Links ]

Thompson, John (1998), Los media y la modernidad. Una teoría de los medios de comunicación, España: Paidós Comunicación. [ Links ]

Torres, Mauricio (2012), "#Yosoy132 y la cercanía de la elección impulsan 'rating' de segundo debate”, CNN México. Disponible en: Disponible en: http://mexico.cnn.com/nacional/2012/06/11/yosoy132-y-la-cercania-de-la-eleccion-impulsan-rating-de-segundo-debate , [10 de julio de 2012 ]. [ Links ]

Van Dijk, Teun (1990), La noticia como discurso: comprensión, estructura y producción de la información, España: Paidós. [ Links ]

Wyatt, Robert (2000), "Televised Presidential Debates and Public Policy", enJournalism and Mass Communication Quarterly , núm. 1, vol. 77, Estados Unidos: Sage . [ Links ]

Zhang, Weiwu (2000), "An Interdisciplinay Synthesis of Framing”, ponencia presentada en la Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, agosto, Estados Unidos. [ Links ]

1 The perspective here implement is indebted to the Anglo tradition similar, but distinguishable from the development related to the spectacularization of politics, trend of critical political sociology and philosophy that boomed in the 1990’s (Debray, 1993; Thompson, 1998; Edelman, 1991) and remains valid up to the present (Aruguete, 2013; Serpa, 2013), centered on the media displays of political actors that used forms of visible staging, personalizing and theatrical, with a heavy load of populism. The concept of infotainment, conversely, is considered broader, as it involves more subtle and general modalities of entertainment in fiction, journalism or social media products (Baym, 2008; Berrocal et al., 2012).

2 The conceptualization here used is specifically applicable to journalistic frames, which can be understood as schemas or principles to treat information that manifest in the selection and exclusion of certain observables, emphasis on some of them and their organization in a discourse that presents them in function of a determinate meaning (Igartua et al., 2007; Muñiz, 2011; Reese, 2010; Zhang, 2000). The generation of frames journalists, as internalized guidance to process information (Klein, 2000), is governed by institutional constrictions, routines, practices or ideologies that enable them to discriminate what topic to select and which emphasis and meaning to give them (Sádaba et al., 2007).

3 Unlike the first contest frames, the latter were not described in the theoretical framing of this work, so we will provide a minimal definition. The frame of “topics, policies and ideas” focuses on the topics and solutions of public policy, personal stances and their consequences; the “political process” framing describes the formal processes, events and occurrences inherent to the campaign, which comprises events and judicial processes and funding of the campaign; while “political leadership” characterizes, as the name defines, the candidates’ leadership in terms of ideology, character and biographic background.

4 Graphs and tables are in Annex, at the end of the present article al final (Editor’s note).

Received: January 11, 2016; Accepted: September 09, 2016

texto em

texto em