Introduction

Auditory signals are widely employed by anurans in different contexts. Currently, four categories of auditory signals are recognized: reproductive calls, aggressive calls, defensive calls and feeding calls (Köhler et al., 2017). Distress call is the most common into defensive call category, which consists of acoustic signals emitted generally by an individual with open mouth before a predator attack, commonly being a loud scream or high pitched hissing (Bogert, 1960; Wells, 2007; Toledo & Haddad, 2009; Köhler et al., 2017). Although the presence of distress call has been relatively well documented in some species of Hylidae and Leptodactylidae, this type of call remains poorly documented in most Neotropical frogs (Hödl & Gollman, 1986; Toledo & Haddad, 2009). Las Hermosas robber frog, Pristimantis racemus (Lynch, 1980) is an endemic and little-known Strabomantidae species that inhabits in paramos ecosystems of the departments of Tolima, Quindío and Valle del Cauca in the Andean region of Colombia, between 3030 and 3570 m a.s.l (Lynch, 1980; Ardila-Robayo & Acosta-Galvis, 2000; Lynch & Suarez-Mayorga, 2002; Buitrago-González et al., 2016; Yánez-Muñoz et al., 2019; Acosta-Galvis, 2022).

This species is listed as Vulnerable and there is limited information about natural history, ecology, geographical distribution, phylogeny, population status and trends (IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group, 2019). Here, we describe the distress call given by a female of P. racemus and report a new locality extending the geographical distribution of the species.

Materials and methods

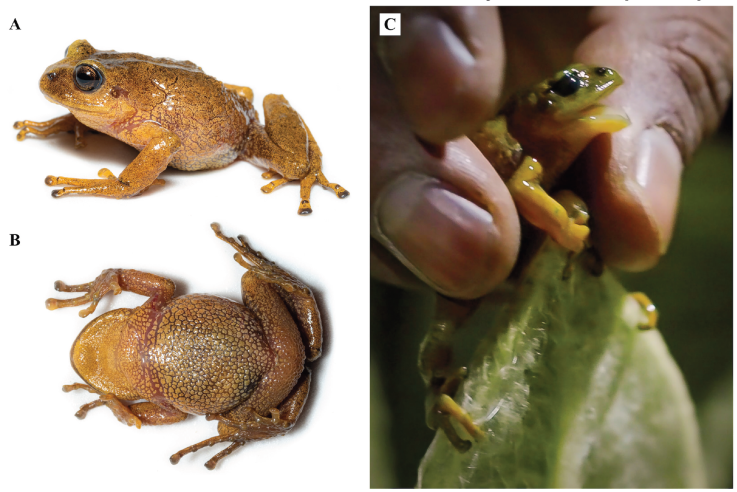

During a field work on December 7th 2021, at 22:04 h, we observed an individual active of P. racemus (Fig. 1) at a height of 100 cm on the leaf of frailejón (Espeletia sp.), located on the driest area of Magdalena Lake at Puracé National Park, municipality of San Agustín, department of Huila, Colombia (1.936278° N, 76.606293° W, datum WGS84, 3,465 m a.s.l.). We captured the individual by handling to obtain Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis samples using the swabbing method (Kriger et al., 2006) and, at the moment of capturing it, the individual began to emit “distress calls” with the open mouth while the frog was manipulated and released again in a frailejón (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1 Pristimantis racemus, A) dorsolateral view, B) ventral view and C) individual manipulation of a female emitting distress call. Individual recorded from Magdalena lake, Puracé National Park, Huila department, Colombia. / Figura 1. Pristimantis racemus, A) vista dorsolateral, B) vista ventral y C) manipulación individual de una hembra emitiendo llamada de auxilio. Individuo registrado en la laguna La Magdalena, Parque Nacional Natural Puracé, departamento del Huila, Colombia.

The individual emitted several distress calls for about five minutes after being handled, but once captured and placed in the bag, not further auditory signals were produced. The distress calls were recorded with a Tascam DR-40X digital recorder connected to a Rode NTG1 unidirectional condenser microphone (frequency range: 20-20,000 Hz) positioned about 0.5 m from the frog. We measured the body size (Snout-Vent Lenght, SVL) with a SPI super polymid dial caliper (± 0.1 mm), while air temperature (ºC) and humidity (%RH) were recorded with HTC-2 digital thermohygrometer (accuracy ± 0.1 ºC and 1 %). The individual was collected as voucher, euthanized with 2% lidocaine, fixed in 10% formaldehyde solution, and preserved in 70% ethanol (Cortez et al., 2006). The specimen was deposited at the herpetological collection of the Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad del Cauca (MHNUC-He-An 001411), in Popayán, Cauca, Colombia. We determined the sex and maturity by direct observation of gonads (i.e., matured testes in adult males or convoluted oviducts or eggs in adult females; Duellman & Lehr, 2009).

Recording was digitized at 16 bits resolution and 44,100 Hz sampling rate. We estimated call duration, peak frequency, minimum frequency (frequency 5%), maximum frequency (frequency 95%) and frequency bandwidth (BW 90%) of the recorded call using the software Raven Pro 1.6.1 (Center for Conservation Bioacoustics, 2019; Cuestas-Carrillo & Dena, 2019). Oscillograms, spectrograms and power spectrum were made with Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT), a window size of 5 ms, the Blackman algorithm, and plotted with the seewave 2.1.8 package in R environment through RStudio interface (Sueur et al., 2008; R Core Team, 2021; RStudio Team, 2022). Data provided for the call include mean ± standard deviation (range). Vocalization recording was deposited at the Colección de Sonidos Ambientales “Mauricio Álvarez-Rebolledo” of the Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH-CSA-36557), Villa de Leyva, Boyacá, Colombia.

To verify the identity of the species, we removed a piece of liver tissue from the collected individual, which was preserved in 96% ethanol (González & Arenas-Castro, 2017), we also obtained a sample liver muscle of P. racemus of the Colección de Anfíbios del Instituto Humboldt (IAvH-Am-13775). DNA was extracted with Blood and Tissue kit from Quiagen. We barcoded the samples for 565 bp of the mitochondrial 16S and 630 bp of COI region, amplified with primers 16S A-L / 16SB-H for 16S (Palumbi, 1996), and dgLCO-1490/dgHCO-2198 for COI (Meyer, 2003). All reactions were carried out using the conditions suggested by Ivanova et al. (2006). We sequenced the amplicons in the forward and reverse direction on an Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA Analyzer. Sequences were deposited on GenBank (Genbank numbers OP578693-OP578694 for 16S and OP580480-OP580481 for COI). For comparative material, we obtained 44 sequences of closely related P. orcesi paraphyletic group (Lynch, 1980) sequences from GenBank. All sequences were aligned using Geneious prime 2019.0.4 (Kearse et al., 2012) and, we estimate molecular divergence levels between clades by calculating pairwise genetic p-distances using Mega 7.0.26 (Kumar et al., 2018), on a shorter dataset of 571 bps for COI and 565 for 16S without missing data and applying pairwise deletion for gaps.

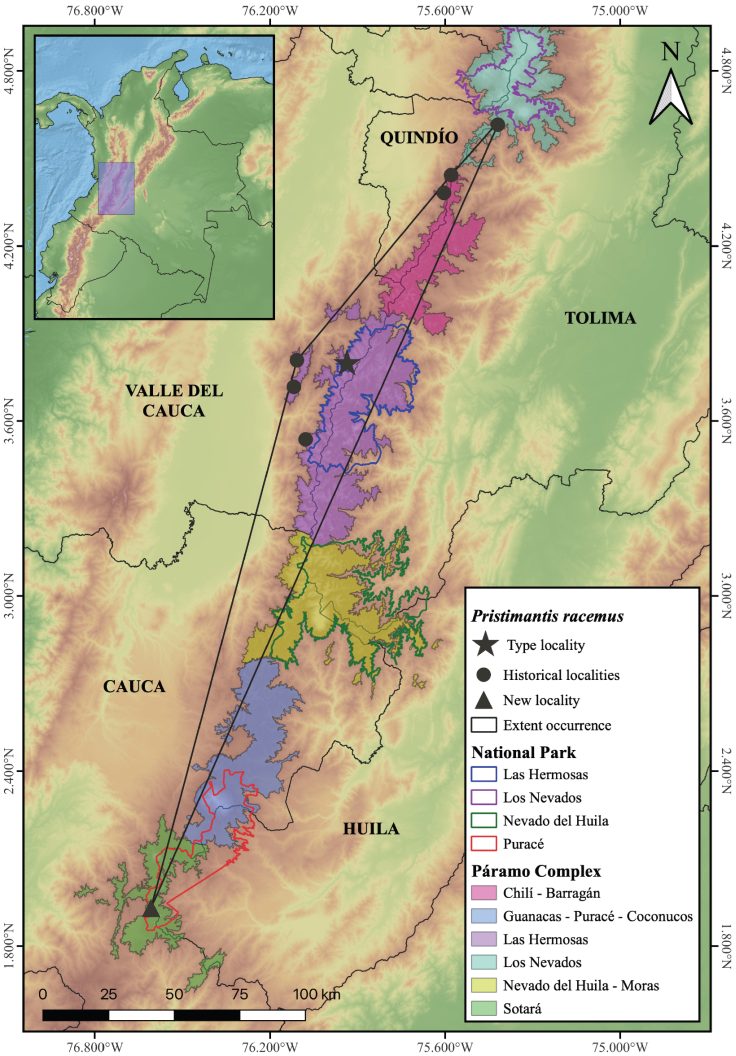

To gather additional geographical data for P. racemus in Colombia, we searched in the local museum databases of the Instituto Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH), Instituto de Ciencias Naturales de la Universidad Nacional (ICN), Universidad del Quindio (ARUQ), Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad del Cauca (MHNUC), and international databases such as the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), National History Museum Los Angeles County (LACM), and the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute Herpetology Collection (KUH), through the use of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF.org, 2022). The geographical coordinates obtained were reviewed for adjustment or approximate assignment by the authors based in the own knowledge of the area. We estimated the actual distribution range of this species using the geometric convex hull polygon, calculated from Minimum Bounding Geometry algorithm in QGIS 3.22 (Ortega-Andrade & Venegas, 2014; QGIS.org, 2022).

Results

The individual is assigned to P. racemus and present several diagnostic morphological traits described by Lynch (1980) as snout-vent length of 29.5 mm (SVL), presence of large flat warts in flanks and lower back, venter coarsely areolate, tympanic annulus and tympanum present, small tubercles in the tarsus and heel, snout round and short (Fig. 1A-B), dentigerous process of the vomer small and oblique, first finger shorter than second and flared lips posteriorly. Moreover, the molecular analysis show that the specimen is close-related to P. racemus (IAvH-Am-13775) with a divergence of 8.1 % for COI and 2.3 % for 16S, the next lower distances are with P. myops (p-distance of 19.0 % for COI and 9.8% for 16S).

We recorded 11 distress calls with a total of 113.72 s for an adult female with convoluted oviducts (T = 7.3 °C; RH = 94 %). The distress calls present a dense harmonic single note (Fig. 2) with an average duration of 3.386 ± 1.654 (0.493-6.241) s, the peak of dominant frequency is 8,699.4 ± 2,807.7 (1,808.8-12,058.6) Hz and the 90% of energy is located between 4,933.1 ± 1,939.8 (775.2-7,062.9) Hz and 13,930.0 ± 2,288.9 (9,905.3-18,260.0) Hz. The dominant frequency varied between the fourth and ninth harmonic with ascending and descending frequency modulation between 7,945.3 ± 1,263.7 (6,221.2-9,932.4) Hz and 12,420.9 ± 767.3 (10,727.0-13,545.0) Hz, respectively. We observed 12 to 28 harmonic bands and it is possible the presence of additional harmonics above the ultrasonic range (Fig. 2) but the unidirectional microphone only can detect auditory signals until 20,000 Hz. In addition to defensive vocalization, the female of P. racemus secreted a strong odor that we detected during manipulation.

Figure 2 Distress call of a female of Pristimantis racemus (MHNUC-He-An 001411); spectrogram (top), oscillogram (bottom), and power spectrum (right). Sampling rate: 44,100 Hz. Voucher call (IAvH-CSA-36557). / Figura 2. Llamado de auxilio de una hembra de Pristimantis racemus (MHNUC-He-An 001411); espectrograma (arriba), oscilograma (abajo) y espectro de potencia (derecha). Frecuencia de muestreo: 44,100 Hz. Registro de la vocalización (IAvH-CSA-36557).

From the geographical data gathered, we obtained 140 records of P. racemus from eight localities belonging to four departments (Tolima, Quindío, Valle del Cauca, Huila) in the Andes of Colombia. The new record from the Magdalena lake occurs in well-preserved ecosystems of the Puracé National Park and corresponds to the most southern record for the species. We extend the distribution range of P. racemus in 216 km from the type locality (Tenerife, Valle del Cauca) and 187 km from the most southern locality previously known for the species (Amaime river, La Victoria Farm, La Nevera village, Valle del Cauca; Fig. 3).

Figure 3 Map showing all know localities for Pristimantis racemus, including the present-day extent of the species’ occurance. Historical records obtained from Instituto Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH), Instituto de Ciencias Naturales de la Universidad Nacional (ICN), Colección de Anfibios y Reptiles de la Universidad del Quindío (ARUQ), Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad del Cauca (MHNUC), American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), National History Museum Los Angeles County (LACM), University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute Herpetology Collection (KUH). / Figura 3. Mapa que muestra todas las localidades conocidas de Pristimantis racemus, incluida la extensión real de la especie. Registros históricos obtenidos del Instituto Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH), Instituto de Ciencias Naturales de la Universidad Nacional (ICN), Colección de Anfibios y Reptiles de la Universidad del Quindío (ARUQ), Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad del Cauca (MHNUC) , Museo Americano de Historia Natural (AMNH), Museo Nacional de Historia del Condado de Los Ángeles (LACM), Colección de Herpetología del Instituto de Biodiversidad de la Universidad de Kansas (KUH).

Discussion

Distress calls in direct-developing frogs have rarely been documented, with Eleutherodactylus zeus, Haddadus binotatus and Holoaden bradei being the only species with a description or record for this type of defensive vocalization (Alonso et al., 2007; Toledo & Haddad, 2009; Martinelli & Toledo, 2016). The call described here for P. racemus is the first description of a distress call for Pristimantis, and show a similar structure to that reported for H. bradei, mainly in high-pitched frequencies, dense harmonic structure and repeated ascending and descending modulations in frequency, and from H. binotatus reaching ultrasound frequencies (Toledo & Haddad, 2009; Martinelli & Toledo, 2016). Heterospecific distress calls in Neotropical anurans tends to have similar structures and therefore, these types of calls do not provide reliable taxonomic information (Hödl & Gollman, 1986; Toledo & Haddad, 2009; Köhler et al., 2017). Similar distress calls have been reported for other Neotropical frogs like Boana lanciformis (Hödl & Gollman, 1986), B. lundii (Toledo & Haddad, 2009), Bokermannohyla circumdata (Toledo & Haddad, 2009), Hyloscirtus larinopygion (Duarte-Marín et al., 2019), Smilisca baudinii (Mendoza-Henao, 2021), Leptodactylus fuscus (Toledo & Haddad, 2009), L. knudseni (Cuestas-Carrillo & Dena, 2019) and L. ocellatus (Hödl & Gollman, 1986).

The use of multiple defenses like longer and powerful defensive vocalizations associated with chemical defense would be effective to avoid predation attempts (Toledo & Haddad, 2009). However, predators of P. racemus are unknown and available information for other Pristimantis frogs shows multiple predators (spiders, birds, reptiles and other frogs; Wizen & González de Rueda, 2016; Escamilla et al., 2020; Eversole et al., 2020; Pinheiro-Freitas et al., 2021; Tipatinza -Tuguminago & Medrano-Vizcaíno, 2020; Cárdenas-Ortega & Cárdenas-Ortega, 2022; Cárdenas-Ortega & Herrera-Lopera, 2016).

Therefore, we suggest that P. racemus could use a repertoire of anti-predatory strategies that combines the distress call and odor that could be related with noxiousness and/or unpalatability, as an attempt to escape, intimidate or repel potential predators trying to surprise or produce an unpleasant sensation (Smith et al., 2004; Toledo & Haddad, 2009; Duarte-Marin et al., 2019) but experimental evidence is needed to validate this assumption.

The molecular evidence supports the assignment of P. racemus, where some authors suggested that minimum genetic distances for candidate species are 3 % for 16S and 10 % for COI (Vences et al., 2005; Fouquet et al., 2007). With this record, we update the P. racemus distribution in Andean ecosystems on Central Andes of Colombia, where it inhabits in the paramo complexes of Los Nevados, Chilí-Barragán, Las Hermosas (Buitrago-González et al., 2016), Nevado del Huila-Moras, Guanacas-Puracé-Coconucos (Lynch, 1980; Ruiz-Carranza et al., 1996; Acosta-Galvis, 2000; Ardila-Robayo & Acosta-Galvis, 2000; Lynch & Suarez-Mayorga, 2002; Yánez-Muñoz et al., 2019; Acosta-Galvis, 2022) and Sotará (this study). The actual extent occurrence of P. racemus is 5,524.2 km2, showing the restricted distribution of the species and the needed to maintain the páramo ecosystems where it inhabits. Our evidence is not enough to suggest changes in the threatened category of the species (IUCN, 2012).

Conclussion

We describe the distress call emitted by a female of P. racemus, and record the species in the Puracé National Park, which extend the known distribution of the species 187 km to the south. It is necessary to explore the Colombian Massif to find additional diversity, especially in the poorly explored protected areas as Complejo Volcánico Doña Juana Cascabel, Nevado del Huila and Puracé. On the other hand, our observation shows an unknown defensive behavior for the genus Pristimantis as the distress call. At the same time, this species used the odor as an anti-predatory strategy that could be related with toxicity or unpalatable.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)