Highlights

The agricultural area in the region of Los Ríos of Tabasco increased 435 % in 72 years.

Natural vegetation suffered the greatest loss of area (53.7 %) between 1947 and 1984.

Between 1947 and 2019, 64 % of the region's natural vegetation was lost.

The expansion of agricultural land was driven without considering the environmental factor.

Introduction

The interaction of humans with the biophysical elements of a territory generates structural changes at the landscape-ecosystem level (Sewnet & Abebe, 2018). The expansion of the agricultural frontier, extensive livestock farming and population growth have caused the loss of 73 % of tropical forests worldwide (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], & United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP], 2020; Rojas et al., 2020). This has resulted in increased pressure on other land, water and nutrient uses (Dhar, Chakraborty, Chattopadhyay, & Sikdar, 2019; Lone & Mayer, 2019); loss of biodiversity, ecosystem services, habitat for wildlife species (Liu et al., 2019; Hasan, Zhen, Miah, Ahamed, & Samie, 2020); and soil degradation through erosion and desertification processes (Obade & Lal, 2013).

In Mexico, crop and grassland areas increased 21 % (Velázquez et al., 2002), parallel to deforestation of 8.3 % of forests and rainforests between 1976 and 2007 (Rosete-Vergés et al., 2014). In Tabasco, agricultural use deforested 63.4 % of rainforests in the period 1940-2006 (Zavala-Cruz & Castillo-Acosta, 2007). The agricultural projects Plan Chontalpa and Plan Balancán-Tenosique deforested 245 000 ha of rainforests and secondary vegetation between 1960 and 2000 (Geissen et al., 2009; Isaac-Márquez et al., 2008). In recent decades, land-use change in Tabasco has been associated with the establishment of grassland and crops, timber extraction, oil industry, roads, human settlements and forest fires, which have affected forests, mangroves and secondary vegetation (Geissen et al., 2009; Ramos-Reyes, Palomeque de la Cruz, Núñez, & Sánchez-Hernández, 2019).

Changes in land cover and land use, and their environmental and social repercussions, require the development of procedures for their quantification at low cost and with greater precision over large geographic areas (Yulianto, Prasasti, Pasaribu, Fitriana, & Zylshal-Haryani, 2016). The analysis of remotely sensed materials (aerial photographs, satellite imagery and drones), using efficient and reliable Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to handle large volumes of information (Chuvieco, 2002), has boosted thematic coverage mapping (Yulianto et al., 2016). Thus, the multitemporal study of land use and vegetation contributes to the understanding of land cover variations and trend prediction, with useful information for planners and decision makers to propose actions for sustainable development, land management and mitigation of environmental problems and climate change (Hasan et al., 2020; Tahmasebi, Karami, & Keshavarz, 2020). The objective of this study was to analyze land use change and its effect on natural vegetation in the region of Los Ríos, Tabasco, Mexico, for the period 1947-2019.

Materials and Methods

The study was carried out in the region of Los Ríos, municipalities of Balancán, Emiliano Zapata and Tenosique in the east part of Tabasco (Figure 1), in an area of 6 234.2 km2 (24.7 % of the state). The region is bordered to the north and west by the states of Campeche and Chiapas, and to the east and south by the Republic of Guatemala. From north to south, the climates are warm sub-humid with summer rainfall (Aw), warm humid with abundant summer rainfall (Am) and warm humid with abundant rainfall all year round (Af); mean annual precipitation ranges from 1 600 to 2 000 mm and mean annual temperature from 26 to 28 °C (Aceves-Navarro & Rivera-Hernández, 2019). The region has geoforms of plains, hills and mountains drained by the Usumacinta and San Pedro rivers (Salgado-García et al., 2017).

Data sources for land use and vegetation cover mapping

Aerial photographs from 1947 at a scale of 1:20 000 were taken from Aerofoto. For 1984, 2000 and 2019, satellite images with pixel size of 30 x 30 m were downloaded from the United States Geological Survey portal (Landsat collection 1 level-2,- on-demand) (Table 1) with atmospheric and geographic correction (United States Geological Survey [USGS], 2019). The images had low percentage of cloud cover, except for the July 2019 image in the south part, which was resolved by generating a cloud layer from that month and cropping the cloud-free image from March of the same year; this image complemented the July image. A similar procedure was performed by Lin, Tsai, Lai, and Chen (2013) in areas with cloud cover.

Table 1 Characteristics of the satellite images used in the land use change analysis of the Los Ríos region, Tabasco, Mexico.

| Date of purchase | Satellite | Sensor identifier | Resolution (m) | Path | Row | Cloud cover (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 25, 1984 | Landsat 5 | TM | 30 x 30 | 21 | 48 | 0 |

| December 5, 1999 | Landsat 5 | TM | 30 x 30 | 21 | 48 | 2 |

| March 31, 2019 | Landsat 8 | OLI_TIRS | 30 x 30 | 21 | 48 | 1 |

| July 5, 2019 | Landsat 8 | OLI_TIRS | 30 x 30 | 21 | 48 | 0.94 |

Source: United States Geological Survey (USGS, 2019).

Classification of aerial photographs and satellite images

Aerial photographs from 1947 were georeferenced and photointerpreted based on tone and texture criteria to generate a vector layer of land use and vegetation cover (Chuvieco, 2002). In the preprocessing of these images, band stacking was used to convert them into a single layer, the area of interest of each image was cropped and the natural color band combinations 3-2-1 (red: 3, green: 2, blue: 1) and 4-3-2 for near infrared (red: 4, green: 3, blue: 2) were made (Chuvieco, 2002; Congedo, 2016).

Literature and cartography on land use and vegetation types of the Los Ríos region were reviewed (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI], 1984, 2017; López-Mendoza, 1980; Vázquez-Negrín, Castillo-Acosta, Valdez-Hernández, Zavala-Cruz, & Martínez-Sánchez, 2011) (Table 2). Subsequently, satellite images were visually interpreted by comparing mapping information with spectral signatures of the RGB band combination (3-2-1 and 4-3-2) at each date; hue variations were associated with land use classes and vegetation types (Tarawally, Wenbo, Weiming, Mushore, & Kursa, 2019) found in the literature review. Regions of interest were then created for each land use and vegetation class (Congedo, 2016) and proceeded to supervised classification (Obodaia, Adjei, Odaia, & Lumor, 2019). The satellite images were analyzed with the Semi-Automatic Classification Plugin (SCP) extension which is a free and open-source add-on to QGIS 3.8.3 software (Congedo, 2016; Dhar et al., 2019).

The accuracy of the land use and vegetation map from 2019 was evaluated using Google Earth Pro version 7.3.4 software and a random sampling of sites with land uses, vegetation, water bodies and human settlements; geographic coordinates were stored in a Garmin eTrex GPS; and 644 points were validated in the field. Classification efficiency was achieved by overlaying the validated site information on the use and vegetation cover map, a confusion matrix was determined, and the Kappa index was estimated (Dhar et al., 2019; Obodaia et al., 2019).

Table 2 Land uses and vegetation types of the Los Ríos region, Tabasco, Mexico.

| Cover | Key | Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Temporary crop | TC | Maize (Zea mays L.), sorgum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench), rice (Oryza sativa L.), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), squash (Cucurbita argyrosperma H.) |

| Annual crop | AC | Papaya (Carica papaya L.), sugar cane (Saccharum officinarum L.) |

| Permanent crop | PC | Oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) |

| Forest plantations | PF | Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus grandis W.), teak (Tectona grandis L.), gmelina (Gmelina arborea Roxb.), cedar (Cedrela odorata L.) |

| Grassland | G | Pennisetum purpureum A., Paspalum dilatatum P., Panicum maximum Jacq. |

| Evergreen rainforest | EF | Guatteria anomala R. E., Dialium guianense L., Calophyllum brasiliense L., Brosimum alicastrum Sw. |

| Rainforest and semi-evergreen seasonal forest | RF | Bucida buceras L., Cedrela odorata L., Piscidia piscipula L., Tabebuia rosea Bertol. |

| Flooded forest | FF | Pachira aquatica Aubl., Annona glabra L., Haematoxylum campechianum L. |

| Savanna | S | Curatella americana L., Byrsonima crassifolia L., Crescentia alata K., Crescentia cujete L. |

| Secondary vegetation | SV | Plants from native vegetation affected by human activities |

| Hydrophytic vegetation | HV | Thalia geniculata L., Typha domingensis Pers., Cladium jamaicense L. (Crantz) |

| Human settlement | HS | Urban demographic conglomerate |

| Bare soil | BS | Vegetation-free area |

| Water bodies | Ca | River and lagoon |

The accuracy of the maps from 1947, 1984, and 2000 was evaluated with cartography and information from regional land use and vegetation cover studies (Estrada-Loreto, Barba-Macias, & Ramos-Reyes, 2013; Hernández-Rojas, López-Barrera, & Bonilla-Moheno, 2018; López-Mendoza, 1980; INEGI, 1984, 2001). For each year, cartography was georeferenced and overlaid on the land use and vegetation cover maps of the classified satellite images, geographically referenced points were generated, and confusion matrices and Kappa indices were developed (Dhar et al., 2019; Obodaia et al., 2019; Tarawally et al., 2019).

Land use change and vegetation cover analysis

Land use and vegetation change was analyzed by superimposing and comparing the maps using the Land Change Modeler module integrated in the TerrSet program, which provides land use change maps and graphs of gains and losses, net change and persistence of specific transitions (Clark Labs, 2009; Tarawally et al., 2019).

Results

Land use and vegetations for the period 1947-2019

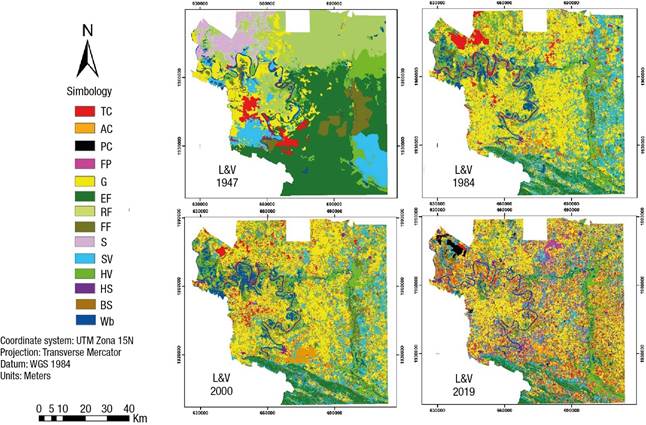

Land use and vegetation maps from 1947, 1984, 2000 and 2019 had an accuracy of 75.8 %, 72.7 %, 75.2 % and 71.1 % respectively, and Kappa indices were 0.72, 0.69, 0.73 and 0.68 for those years. Table 3 and Figure 2 show the areas by land use for the period 1947-2019.

By 1947, agricultural areas and grasslands were distributed over 14.1 % of the Los Ríos region. Natural vegetation occupied the largest area (82.3 %), dominated by rainforests (evergreen rainforest [EF], rainforest and semi-evergreen seasonal forest [RF] and flooded forest [FF]) with 61.5 %, followed by savanna, secondary and hydrophytic vegetation. Human settlements, bare soil and water bodies occupied small areas.

The largest area of the region (54.3 %) was occupied by agricultural uses in 1984, with a greater coverage of grasslands and lesser coverage of crops. Vegetation areas had different trends; rainforests reduced their surface area to 12.9 %, savanna disappeared and secondary and hydrophytic vegetation increased (26.1 %). Human settlements, bare soil and water bodies increased their area.

Agricultural uses occupied 52.7 % of the land in 2000, with a predominance of grasslands over crops. Forest plantations appeared in a minimal area. The area covered by rainforests remained the same (13 %), secondary vegetation decreased and hydrophytic vegetation increased slightly. Human settlements, bare soil and water bodies continued to grow (11.7 %).

By 2019, agricultural uses reached the largest area (60.5 %) with increases in grasslands and temporary and permanent crops. Forest plantations expanded their area. Forest vegetation decreased to 10 %, secondary vegetation remained the same and hydrophytic vegetation decreased. Human settlements and bare soil continued to grow and water bodies lost surface area.

Table 3 Land use areas and vegetation types for the period 1947-2019 in the Los Ríos region, Tabasco, Mexico.

| Cover | 1947 | 1984 | 2000 | 2019 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (km2) | Percentage (%) | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) | Area (km2) | Percentage (%) | |

| Temporary crop | 140.8 | 2.6 | 358.1 | 6.6 | 300.6 | 5.5 | 864.2 | 15.8 |

| Annual crop | - | - | 548.9 | 10.1 | 884.2 | 16.2 | 357.3 | 6.5 |

| Permanent crop | - | - | - | - | - | - | 94.7 | 1.7 |

| Forest plantations | - | - | - | - | 6.3 | 0.1 | 241.4 | 4.4 |

| Grassland | 628.4 | 11.5 | 2 051.4 | 37.6 | 1 689.8 | 30.9 | 1 753.6 | 32.1 |

| Evergreen rainforest | 1 782.9 | 32.7 | 338.3 | 6.2 | 314.5 | 5.8 | 275 | 5 |

| Rainforest and semi-evergreen seasonal forest | 1 296.3 | 23.7 | 94.6 | 1.7 | 70.6 | 1.3 | 131.7 | 2.4 |

| Flooded forest | 280.5 | 5.1 | 272.8 | 5 | 323.5 | 5.9 | 141 | 2.6 |

| Savanna | 310.2 | 5.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Secondary vegetation | 473.8 | 8.7 | 1 044.1 | 19.1 | 823.4 | 15.1 | 812 | 14.9 |

| Hydrophytic vegetation | 348.6 | 6.4 | 382.4 | 7 | 402.7 | 7.4 | 263.9 | 4.8 |

| Human settlement | 3.2 | 0.1 | 41.1 | 0.8 | 51.3 | 0.9 | 64 | 1.2 |

| Bare soil | 3.9 | 0.1 | 56.5 | 1 | 262.9 | 4.8 | 291.8 | 5.3 |

| Water bodies | 191.6 | 3.5 | 271.8 | 5 | 330.1 | 6 | 169.3 | 3.1 |

| Total | 5 459.9 | 100 | 5 459.9 | 100 | 5 459.9 | 100 | 5 459.9 | 100 |

Figure 2 Land use and vegetation cover (L&V) for the period 1947-2019 in the region of Los Ríos, Tabasco, Mexico. TC = temporary crop, AC = annual crop, PC = permanent crop, FP = forest plantations, G = grassland, EF = evergreen forest, RF = rainforest and semi-evergreen seasonal forest, FF= flooded forest, S = savanna, SV = secondary vegetation, HV = hydrophytic vegetation, HS = human settlement, BS = bare soil, Wb = water bodies.

Land use and vegetation cover dynamics for the period 1947-2019

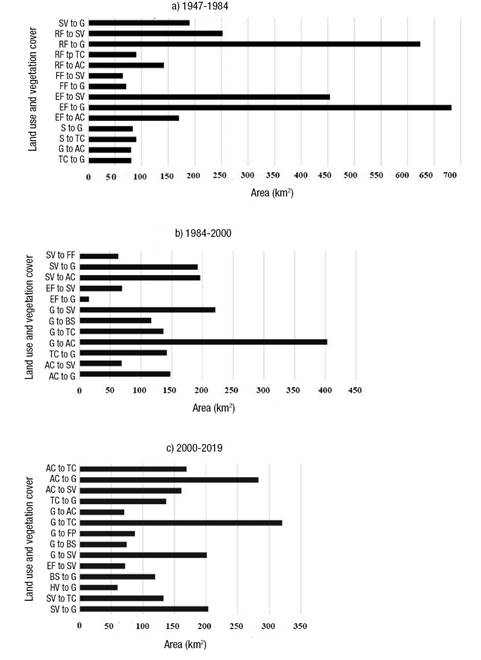

Table 4 shows the balance between losses, gains and net change of agricultural land use, vegetation cover and others, between 1947 and 2019; the data show different dynamics in the Los Ríos region. Crops and grasslands had the greatest positive net change with 2 185.7 km2 for the period 1947-1984. Between 1984 and 2000, only annual crops showed a positive net change, and the introduction of forest plantations began. For the period 2000-2019, a positive net change was observed in grasslands and crops, except for annual crops. Temporary crops stand out with the highest net favorable change in 72 years, as well as forest plantations and permanent crops that covered 329.5 km2.

Rainforest and savanna vegetation showed negative net changes in all periods, being greater between 1947 and 1984 with 1 622.9 km2. Secondary and hydrophytic vegetation showed positive net changes between 1947 and 1984, and negative between 1984 and 2019.

Human settlements and bare soil showed positive net changes in all three assessment periods, while water bodies showed positive net changes between 1947 and 2000, and negative between 2000 and 2019.

Transition of vegetation cover and land use change

Based on Figure 3, between 1947 and 1984, the main change from rainforest, savanna and secondary vegetation was to grassland, followed by annual and temporary crops. Some areas of grassland and temporary crops changed to other agricultural use. For the periods 1984-2000 and 2000-2019, the biggest changes occurred in the agricultural use zone. The alternation was from grassland to crops, forest plantations and secondary vegetation, and from crops to grassland and secondary vegetation. Secondary and hydrophytic vegetation changed to grassland and crops, and rainforest to secondary vegetation.

Table 4 Land use and vegetation cover (L&V) dynamics in the region of Los Ríos, Tabasco, Mexico, for the period 1947-2019.

| 1947-1984 | 1984-2000 | 2000-2019 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L&V | Loss (km2) | Gain (km2) | Change (km2) | Persistency (km2) | Loss (km2) | Gain (km2) | Change (km2) | Persistency (km2) | Loss (km2) | Gain (km2) | Change (km2) | Persistency (km2) |

| TC | -124.9 | 342.2 | 217.2 | 15.7 | -293.1 | -235.6 | -57.5 | 65 | -252.9 | 816.3 | 563.4 | 47.7 |

| AC | 0 | 548.3 | 548.3 | 0 | -400 | 735.3 | 335.3 | 148.9 | -800.4 | 273.7 | -526.7 | 83.6 |

| PC | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0 | 94.7 | 94.7 | 0 |

| FP | - | - | - | - | 0 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 0 | -6.2 | 241 | 234.8 | 0.1 |

| G | -360 | 1 780.1 | 1 420.1 | 269.8 | -961.9 | 600.3 | -361.6 | 1 089.5 | -868.7 | 932.5 | 63.9 | 821.2 |

| EF | -1 530.7 | 74.8 | -1455.9 | 256.8 | -148.7 | 125 | -23.7 | 190. 2 | -180.6 | 141.3 | -39.4 | 133.6 |

| RF | -1 270.9 | 81.3 | -1 189.6 | 13.3 | -88.5 | 64.6 | -23.9 | 6 | -62.2 | 123.3 | 61.1 | 8.4 |

| FF | -240.2 | 232.6 | -7.5 | 40.1 | -154.8 | 205.5 | 50.7 | 118 | -281.2 | 98.7 | -182.4 | 42.2 |

| S | 310.2 | 0 | -310.2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SV | -359.8 | 934.9 | 575.1 | 106.4 | -673.8 | 453.1 | -220.7 | 30.3 | -630.3 | 618.9 | -11.4 | 193 |

| HV | -228.8 | 261.9 | 33.1 | 119.1 | -200 | 220.3 | 20.2 | 182.4 | -288.3 | 149.4 | -138.9 | 144.1 |

| HS | -3.2 | 41 | 37.9 | 0 | -26.7 | 36.9 | 10.2 | 14.4 | -26 | 38.7 | 12.7 | 25.3 |

| BS | -3.9 | 56.4 | 52.5 | 0 | -47.6 | 254 | 206.4 | 8.9 | -245.8 | 274.7 | 28.9 | 17.1 |

| Wb | -49.3 | 125.3 | 76 | 142.8 | -46.2 | 104.5 | 58.3 | 225.6 | -190.8 | 30.4 | -160.4 | 138.9 |

TC = temporary crop, AC = annual crop, PC = permanent crop, FP forest plantations, P = grassland, EF = evergreen rainforest, RF = rainforest and semi-evergreen seasonal forest, FF = Flooded forest, S = savanna, SV = secondary vegetation, HV = Hydrophytic vegetation, HS = human settlement, BS = bare soil, Wb = water bodies.

Figure 3 Land areas of the main vegetation transitions and agricultural use change in the region of Los Ríos, Tabasco, Mexico. TC = temporary crop, AC = annual crop, PC = permanent crop, FP = forest plantations, G = pasture, EF = evergreen rainforest, RF = rainforest and semi-evergreen seasonal forest, FF = flooded forest, S = savanna, SV = secondary vegetation, HV = Hydrophytic vegetation, HS = human settlement, BS = bare soil.

Discussion

Accuracy values suggest that land use and vegetation maps from 1947, 1984, 2000 and 2019 are acceptable (Dhar et al., 2019) and Kappa (K) indices show that the land use classification is good (Satya, Shashi, & Deva, 2020; Sewnet & Abebe, 2018).

Land use data in the Los Ríos region for the period 1947-2019, with 72-year interval, reveal drastic changes in vegetation. The loss of natural vegetation stands out, since in 1947 it covered 82.3 %, when the largest area corresponded to EF, RF and FF; in 2019, vegetation reached its smallest area with 29.7 %. The most notable loss occurred in rainforest, which decreased from 61.5 % to 10 %. On the contrary, in the same period, agricultural use represented by crops and grassland grew from 14.1 % to 61.8 %; these uses, together with urban use, changed the original ecosystems by deforestation. Vegetation damage in the region is consistent with the increase in agricultural land, grassland and human settlements leading to the destruction of 63.4 % of Tabasco's forests between 1940 and 2006 (Zavala-Cruz & Castillo-Acosta, 2007) and the loss of 8.3 to 13.6 % of Mexico's forests and rainforest between 1976 and 2000 (Rosete-Vergés et al., 2014; Velázquez et al., 2002). Similar changes associated with increased agricultural use and urban settlements have resulted in the loss of natural vegetation (Liu et al., 2019; Mwampamba & Schwartz, 2011; Tarawally et al., 2019), degradation of 73 to 83 % of tropical forests worldwide (FAO & UNEP, 2020; Hamunyela et al., 2020; Rojas et al., 2020) and decrease of biodiversity and environmental services (Bonanomi et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019).

Between 1947 and 1984, natural vegetation in the Los Ríos region suffered the greatest loss of 53.7 % of the area; in contrast, grassland and agricultural uses increased by 385 %. The expansion of grasslands corresponded to the boost of extensive livestock farming (Estrada-Loreto et al., 2013; Isaac-Márquez et al., 2008) and agricultural expansion was reflected in the increase of staple crops (Chowdhury, Emran-Hasan, & Abdullah-Al-Mamuna, 2020; Rojas et al., 2020), especially between the 1940s and 1960s when rural development policy in the region encouraged the production of maize (Zea mays L.), beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), rice (Oryza sativa L.), pepper (Capsicum spp.), squash (Cucurbita argyrosperma H.) and watermelon (Citrullus lanatus Thunb.) (Isaac-Márquez et al., 2008; Reyes Grande, 2015). The implementation of the Balancán-Tenosique plan in 1972 accelerated land use change due to the expansion of grasslands and crops over rainforest (San-Pallo, Ramos-Muñoz, Mesa-Jurado, & Díaz-Perera, 2019).

From 1984-2000, agricultural use continued to predominate in the Los Ríos region (17.4 km2∙yr-1), based on basic temporary crops for self-consumption, including land use with steep slopes and thin soils unsuitable for agriculture (Isaac-Márquez et al., 2008). The opening of croplands was based on the slash-and-burn system and, together with forest fires, reduced vegetation remnants (3 km2∙yr-1), mainly rainforests (Reyes Grande, 2015) and secondary vegetation. The displacement of vegetation surfaces by agricultural uses was comparable to that recorded in tropical areas of Tanzania (Mwampamba & Schwartz, 2011).

Between 1984-2000, annual sugarcane growing expanded, driven by the sugar mill Azsuremex S. A. de C. V., replacing areas of grasslands, crops and vegetation (García-Ortega, 2013); a similar change was observed in a watershed in Sao Paulo, Brazil (Couto-Júnior et al., 2019). Grasslands increased their area by the introduction of brizantha (Urochloa brizantha Hochst. ex A. Rich.) and humidicola (Urochloa humidicola R.) species, to improve livestock production, which contributed to remove remnants of forest, secondary and hydrophytic vegetation. On the other hand, eucalyptus (Eucalyptus) forest plantations were established on small areas (Trujillo-Ubaldo, Álvarez-López, Valdovinos Chavez, Benítez Molina, & Rodríguez Gonzales, 2018). These changes in use agree with that reported by Estrada-Loreto et al. (2013) and Palomeque-De la Cruz, Ruiz-Acosta, Galindo-Alcántara, & Ramos-Reyes (2019) in the study region.

For the period 2000-2019, changes in agricultural uses were dynamic. Temporary crops increased 29.6 km2∙yr-1, perhaps in response to support granted to ejidatarios for staple crops through the ‘Sembrando vida’ program in 2019 (San-Pallo et al., 2019). Inversely, annual crops decreased by a similar area, due to the loss of the 2018-2019 sugarcane harvest at the Azsuremex sugar mill. Permanent oil palm cultivation increased and mostly displaced grassland areas; this crop detonated in 2000 as one of the main crops in Tabasco with support from the federal program ‘Alianza para el Campo’ (Hernández-Rojas et al., 2018; Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera [SIAP], 2018), to increase the production of vegetable fat and agri-diesel (Rodríguez Wallenius, 2017). Grasslands increased sparsely but continued as the main use as forage provider for extensive livestock farming (Geissen et al., 2009; Palomeque-De la Cruz et al., 2019). Forest plantations increased their area with support from the Programa Especial Desarrollo Forestal (PEDF) 2013-2018, supported by native and introduced species such as mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla K.), cedar (Cedrela odorata L.), macuilis (Tabebuia rosea Bertol.), gmelina (Gmelina arborea Roxb.), teak (Tectona grandis L.), African mahogany (Khaya ivorensis A. Chev.), Australian cedar (Toona ciliata M. Roem.) and eucalyptus (Eucalyptus grandis W.). These species have been promoted by the companies Proteak, Agropecuaria Santa Genoveva and Grupo Forestal de México, due to their rapid growth and high commercial value (Comisión Estatal Forestal [COMESFOR], 2015), with the aim of producing timber and pulp for paper (Rodríguez Wallenius, 2017). Along with the growth of agricultural use, rainforest relicts lost surface area, being also affected by the extraction of firewood, poles and timber (Hamunyela et al., 2020; Villanueva-Partida et al., 2019).

Hydrophytic vegetation increased in the period prior to 2000 and then had losses due to the advance of grasslands. The recent deterioration of hydrophytic vegetation surfaces is consistent with the impulse of colonization activities, opening of roads and new agricultural and livestock areas in the Los Ríos region (Estrada-Loreto et al., 2013; Isaac-Márquez et al., 2008) and with the decrease of wetland areas due to the introduction of grasslands for livestock (Ramos-Reyes Palomeque-De la Cruz, Megía-Vera, & Landeros-Pascual, 2021).

Water bodies increased in area between 1984 and 2000 and decreased between 2000 and 2019. The loss of area can be attributed to changes in land use in the upper Usumacinta River basin, decreasing annual precipitation, rising temperatures in recent years, and the moderate to extreme drought that Tabasco experienced in 2019 (Aceves Navarro et al., 2017; Comisión Nacional del Agua [CONAGUA], 2019).

Conclusions

Land use change in the Los Ríos region, for the period 1947-2019, meant the increase of crops, grasslands, forest plantations and urban areas, which together represented 14.2 % and then increased to 61.8 %, i.e., an increase of 535 %. These uses occupied areas of rainforest, savanna and hydrophytic vegetation, which went from 82.3 % to 29.7%, representing a loss of 64 %. Agricultural and forestry uses were promoted by federal government programs in synergy with the demand for basic foodstuffs by the region's inhabitants. The massive loss of natural vegetation in 72 years shows little or no consideration of the environmental in these programs. To mitigate this problem, the information provided can contribute to the implementation of ecological and territorial planning programs; specific activities for the conservation and restoration of forests in mountain landscapes and karstic hills, and wetlands in swamps whose soils lack agricultural capacity; and actions for the sustainable management of agricultural and forestry zones, based on the suitability of soils and environment.

texto en

texto en