Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 no.6 Texcoco ago./sep. 2017

Articles

Genetic effects of Spodoptera frugiperda resistance in maize lines derived from germplasm native of Tamaulipas

1Posgrado e Investigación de la Facultad de Ingeniería y Ciencias-Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas. Cuarto piso del Centro de Generación de Conocimiento, Centro Universitario Victoria. Cd. Victoria, Tamaulipas. CP. 87000. (resendizmorelos.mod4@gmail.com; benestrada@uat.edu.mx; eosorio@uat.edu.mx).

2Postgrado en Recursos Genéticos y Productividad-Genética. Campus Montecillo, Colegio de Postgraduados. Montecillo, Estado de México, México. CP. 56230. (jpecina@colpos.mx; camen@colpos.mx).

The fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) damage maize throughout the life cycle of the plant; one option for this problem is the development and use of resistant cultivars; for this, it is necessary to know the genetic behavior of the characteristics that induce this resistance. S. frugiperda resistance was genetically evaluated by no preference of maize cultivars developed with germplasm native of Tamaulipas; in the autumn-winter cycle 2014-2015, in Güémez, Tamaulipas, in fertilization and non-fertilization treatments, six inbred maize lines derived from native germplasm, its direct and reciprocal crosses and four commercial hybrids were evaluated in a complete random block design; a diallel analysis was performed to determine maternal, reciprocal, general and specific combinatorial effects; leaf damage by S. frugiperda was estimated in the stages of the sixth ligulate leaf (DFH6), tenth (DFH10) and flowering (DFHF). There was minor damage of S. frugiperda in the fertilization treatment compared to the non fertilization one; also statistical differences between cultivars for DFH6 and significant interaction between cultivars and fertilization treatments. PWL1S3×PWL6S3 y TGL2S3×LlHL5S3 crosses had negative effects of specific combining ability; the first showed significant reciprocal effects due to maternal effects of the PWL1S3 line, this shows that the variation for this feature is explained by maternal effects and no additives; additionally DFH6 of S. frugiperda of 0.867 showing lower preference of the insect in comparison to the rest of the cultivars.

Keywords: Zea mays L.; combining ability; diallel; fall armyworm

El gusano cogollero (Spodoptera frugiperda) daña al maíz durante todo el ciclo biológico de la planta; una opción para esta problemática es el desarrollo y utilización de cultivares resistentes; para ello, es necesario conocer el comportamiento genético de las características que inducen esta resistencia. Se evaluó genéticamente la resistencia a S. frugiperda por no preferencia de cultivares de maíz desarrollados con germoplasma nativo de Tamaulipas; en el ciclo otoño- invierno 2014-2015, en Güémez, Tamaulipas, en tratamientos de fertilización y no fertilización se evaluaron seis líneas endogámicas de maíz derivadas de germoplasma nativo, sus cruzas directas y recíprocas y cuatro híbridos comerciales, en un diseño de bloques completos al azar; se realizó un análisis dialélico para determinar efectos maternos, recíprocos, de aptitud combinatoria general y específica; el daño foliar por S. frugiperda se estimó en las etapas de sexta hoja ligulada (DFH6), décima (DFH10) y a floración (DFHF). Hubo menor daño de S. frugiperda en el tratamiento de fertilización comparado con el de no fertilización; también diferencias estadísticas entre cultivares para el DFH6 e interacción significante entre cultivares y tratamientos de fertilización. Las cruzas PWL1S3× PWL6S3 y TGL2S3× LlHL5S3 tuvieron efectos de aptitud combinatoria específica negativa; la primera mostró efectos recíprocos significativos debido a efectos maternos de la línea PWL1S3, esto evidencia que la variación existente para esta característica se explica mediante efectos maternos y no aditivos; además, presen DFH6 de S. frugiperda de 0.867 demostrando menor preferencia del insecto en comparación al resto de los cultivares.

Palabras clave: Zea mays L.; aptitud combinatoria; dialélico; gusano cogollero

Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.) is grown in all agricultural regions of Tamaulipas, in the north for marketing purposes, and in central and south also for own consumption. Due to the wide agroecological variability of these regions, in some cases the cultivars do not express its yield potential, especially in areas with high temperature and humidity restriction. Pest attack is another factor that causes decreased yield and quality of maize grain, being the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) one of the most important (Casmuz et al., 2010). This pest occurs throughout the life cycle of the plant causing damage during larval stage (Nexticapan-Garcéz et al., 2009), the highest infestation occurs during the vegetative stage, in which the larvae feeds preferably on tissue developing, it pierces the leaves and manage to remove full sheets (Casmuz et al., 2010), in advanced stages of plant development this pest can also damage inflorescences, grain and even the rachis of the cob (Bruns and Abbas, 2006).

In México the control of this pest is generally done by chemical methods, which increases the production costs and decreases the profitability of the crop; in addition, the application of chemical insecticides is a source of soil and water pollution, that favors the elimination of beneficial fauna and the development of genetic resistance of pest insect populations (Negrete and Morales, 2003). In other countries the management of this pest has been performed using transgenic cultivars (Díaz, 2015), which can cause the development of Cry toxins resistance to in S. frugiperda populations that interact with this type of cultivars (Casmuz et al., 2010), despite multiple attempts to release the planting of transgenic maize in México, its use is not considered feasible (Massieu, 2009) due to various factors such as possible effects on human health and pollution of the genetic diversity of native maize germplasm, among others (Reséndiz et al., 2016).

In Tamaulipas, all the diversity of native maize germplasm has not been exploited, even though it has been shown to be a high-value genetic resource, since it has only been used in a limited way for the development of some varieties of free pollination, lines and hybrids (Pecina et al., 2011; Castro et al., 2013), moreover, this germplasm has been developed in areas with constant natural infestation of S. frugiperda; so that within the populations there could be useful alleles as a source to improve resistance to pest attack.

Maize resistance to pests, specifically to S. frugiperda, can be caused by one or a combination of three mechanisms: tolerance, antibiosis and antixenosis latter refers to non-preference by the plant for insect oviposition, shelter or consumption (Saldua and Castro, 2011), which is a dependent mechanism of multiple chemical and mechanical factors (Vivanco et al., 2005), which are inheritable, polygenic (Fernández-Northcote 1991) and of high interaction with the environment, enabling the plant not to be chosen by the insect when compared to susceptible or preferred cultivars (Badii and Garza, 2007). Thus, genetic improvement can be a useful tool for obtaining cultivars resistant to this plague; for this, it is necessary to know the basis germplasm used, the type of gene action that controls features that provide this resistance, thus planning an efficient breeding program (Vanegas-Angaritas et al., 2007).

An important decision for the success of a breeding program is the germplasm choice (Bänziger et al., 2012) studies of diallel crosses are tools for estimating genetic effects of general and specific combinatorial ability, reciprocal effects, maternal and no maternal lines and basis populations or premejoradas, which information allows to define heterotic pairs (Griffing, 1956; Guillen et al., 2009) which are used to develop commercial elite maize lines and hybrids; likewise, in random sampling of lines, it is possible to estimate heritability, genetic variance and its components in characters of economic importance.

The effects of general combinatorial ability are associated with additive genetic variance, which can be exploited by recurrent selection methods, and those of specific combining ability to non-additive genetic variance, which can be used in a hybridization program (Ávila et al., 2009). According to the above, the determination of the general and specific combining ability of maize germplasm for resistance characteristics against S. frugiperda, allows the classification of genotypes for its use in breeding programs and to identify individuals who generate progeny with resistance to this plague. Moreover, environmental stress conditions, such as moisture restriction or nutritional deficiencies favor the attack of S. frugiperda to maize, so it is considered that such conditions can enable differentiation of the resistance levels of each cultivar to this pest, facilitating the selection of resistant cultivars. The objective of this research was to genetically evaluate the resistance “for non-preference” of S. frugiperda to maize cultivars derived from native germplasm form central and southern Tamaulipas, evaluated under different fertilization treatments.

Materials and methods

During the autumn-winter 2014-2015 cycle in the Campo Experimental “Ing. Herminio García González” of the Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas, in Güémez, Tamaulipas, six S3 maize lines derived from native germplasm of central and southern Tamaulipas were evaluated; two lines of native populations from Padilla (PWL1S3 y PWL6S3), two from Tula (TGL2S3 y TML3S3) and two from Llera, Tam. (LlNL4S3 y LlHL5S3), 15 direct and 15 reciprocal crosses, plus four commercial hybrids as controls (H-439, H-440, H-443 y G-8801), with a total of 40 cultivars. The cultivars were established in two fertilization treatments: in the first one the 120N-60P-00K formula was applied, where 50% of N and 100% of P was applied in the sowing, the rest of the N in the first weeding and in the second treatment no fertilization was applied (00N-00P-00K). The experiment was established in a randomized complete block design with three replicates, with a split plot arrangement, the large plot was the fertilizer treatment and the small plot the cultivars, the experimental unit consisted of a 5 m long furrow with 0.8 m of furrow spacing.

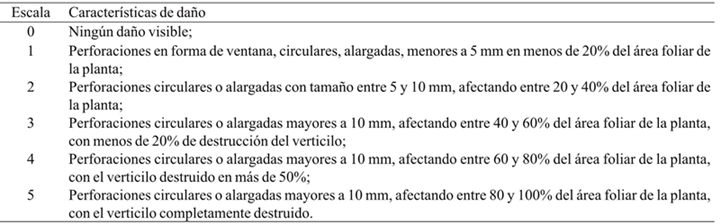

The experiment was set under irrigation, in a population density of 50 000 plants ha-1, planting was done manually on February 20th, 2015, and weed control was performed manually. Leaf damage by S. frugiperda was determined in the phenological stages of sixth (DFH6) and tenth (DFH10) ligulate leaf and at flowering (DFHF) by a damage scale from 0 to 5 (Table 1), the identification of the damage caused by this insect it was performed according the specific features described by Casmuz et al. (2010); Fernández and Esposito (2000), the measurements were made in a sample of five plants per experimental plot and the average per plant was obtained.

Table 1 Visual scale of leaf damage caused by S. frugiperda to maize cultivars developed from native germplasm of central and southern Tamaulipas.

To the average values in each experimental plot from 1 to 5 of the visual scale, a variance analysis and Tukey comparison test (0.05) were performed, the DIALLEL-SAS05 (Zhang et al., 2005) program was used to perform a diallel analysis under the Griffing method I and the model I (fixed effects), and to estimate general, specific and reciprocal combinatorial ability effects, this program allowed the division of the reciprocal effects in maternal and non maternal.

Results and discussion

For DFH6 there were significant differences (p< 0.05) between cultivars and fertilization treatments, while the cultivars×fertilizer treatments interaction was highly significant (p< 0.01), these results indicate that the cultivars had DFH6 different from each other, depending on the fertilization treatment; the effect of fertilization treatment on this variable also depended on the evaluated cultivar (Table 2).

FV= fuente de variación; GL= grados de libertad; SC= suma de cuadrados; CM= cuadrados medios; Rep= repetición; TF= tratamiento de fertilización; CV= coeficiente de variación.

Table 2 Results of combined analysis of variance of 40 maize cultivars in two fertilization treatments for leaf damage by S. frugiperda.

On the other hand, for DFH10 and DFHF, significant differences were observed between fertilization treatments, and in the opposite way between cultivars and for the cultivar×fertilization treatment interaction there was no statistical significance (data not shown); a higher DFH10 and DFHF was observed in the non-fertilization treatment (1.09 and 0.633 respectively) compared to the fertilization treatment (0.603 and 0.4 respectively), this corroborates that, a condition of less nutrients availability for the maize plant causes increased susceptibility to pests such as S. frugiperda (Altieri and Nicholls, 2006), which promotes efficient evaluation and selection of cultivars resistant to this pest. The absence of difference between cultivars for DFH10 and DFHF was due to a decrease in the incidence and leaf damage of this pest in later stages of the crop biological cycle, which shows that this insect has a higher incidence in stages prior to flowering in maize (Murúa et al., 2006; Casmuz et al., 2010).

Taking into account the results of the cultivar×fertilization treatment interaction for the DFH6, each of the major factors was analyzed within each of the other factor levels; in this sense, the non fertilization treatment only favored a higher leaf damage of S. frugiperda in four of 30 evaluated crosses: PWL6S3×LlHL5S3, PWL6S3×LlNL4S3, LlNL4S3×LlHL5S3 and PWL6S3×TML3S3, and in the H-440 control compared to fertility treatment with DFH6 average in non fertilization treatment of 2.639 and in the fertilization of 0.466 (Table 3), the rest of the evaluated cultivars did not show significant effects on DFH6 between fertilization treatments; this shows that the nutrients availability in the soil for the maize plant can influence on the susceptibility level the attack by S. frugiperda (Granados and Paliwal, 2001) and this effect depends on the cultivar (Granados, 2001).

a, b= Promedios con distinta literal por columnas son estadísticamente diferentes; **= promedios estadísticamente diferentes entre tratamientos.

Table 3 S. frugiperda foliar damage in the sixth ligulate leaf stage of maize cultivars in the two fertilization treatments.

On the other hand, no significant statistical differences were observed for DFH6 among cultivars in the treatment with fertilization. Conversely, in the non-fertilization treatment the PWL6S3×LlHL5S3 cultivar had a DFH6 of 2.933, statistically higher than that observed in PWL1S3×PWL6S3, TML3S3×LlHL5S3 and PWL1S3×LlNL4S3 cultivars with averages lower than 0.87 of DFH6; whereas the H-440 control had a DFH6 of 2.733, it only differed from the PWL1S3×LlNL4S3 cross with a DFH6 of 0.733 (Table 3), the rest of the cultivars had similar DFH6 averages. This shows that environmental tension conditions favor the differentiation of the expression of several cultivars (Moreno, 2009), allowing the identification of outstanding characteristics such as resistance to pests; the progenitor lines had a DFH6 in the non-fertilization treatment between 1.067 and 2.333, showing no significant differences between them (Table 3).

For DFH6 no significant effects of general combinatorial ability were found; significant effects of specific combinatorial ability (p> 0.039) were observed, demonstrating that the variation of this characteristic depended mainly on non-additive effects; in this regard, no significance was observed for the interactions of general and specific combinatorial ability×fertilization treatment (Table 4), which indicates that the availability of nutrients in the soil for the plant did not influence the expression of the combinatorial ability effects of the evaluated cultivars.

CM= cuadrados medios; ACG= aptitud combinatoria general; ACE= aptitude combinatorial específica; TF= tratamiento de fertilización; REC= efectos recíprocos; MAT= efectos maternos; NoM= efectos no maternos.

Table 4 Results of dialelic analysis for leaf damage by S. frugiperda in the sixth ligulated leaf stage in maize cultivars developed from germplasm native of Tamaulipas in two fertilization treatments.

For reciprocal effects, no significance was also detected; however, there were for reciprocal effects×fertilization treatment interaction. Significance was observed both for maternal effects and for the interaction of maternal effects×fertilization treatment; however, there was no significance for non-maternal effects or for their interaction with fertilization treatment (Table 4); this shows that the expression of reciprocal and maternal effects depended on the evaluated fertilization treatment. Finally, there was no significance for non-maternal effects (Table 4), which shows that the presence of reciprocal effects for HFD6 depended exclusively on maternal effects, i.e. that the variation between direct and reciprocal crosses was controlled by genes located in extranuclear or cytoplasmic DNA, either in chloroplasts or mitochondria (Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2010).

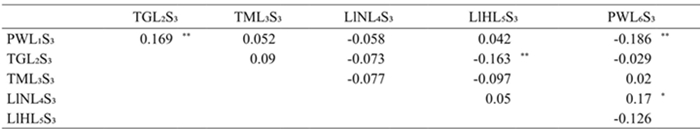

Significant and positive effects of specific combinatorial ability for HFD6 were observed in the PWL1S3×TGL2S3 and LlNL4S3×PWL6S3 crosses and negative for the PWL1S3×PWL6S3 y TGL2S3×LlHL5S3 crosses (Table 5). This indicates that in the first two crosses there is a greater preference from S. frugiperda compared to its progenitors, whereas in the last crosses, the preference decreases in comparison to its progenitors (Table 3). This suggests that non-additive gene action is involved in the indicated crosses (Ávila et al., 2009); that is, the existing variation of the non-preference of S. frugiperda in these, depends on non-additive effects, therefore, by hybridization processes, resistance by non-preference can be increased in this germplasm (De la Cruz-Lázaro et al., 2010).

* y **= Diferente de cero con probabilidad de 0.05 y 0.01 respectivamente.

Table 5 Effects of specific combining ability for leaf damage by S. frugiperda in the sixth ligulate leaf stage in maize cultivars developed from germplasm native of Tamaulipas.

There was significance for the interaction of reciprocal and maternal effects×fertilization treatment (Table 4), indicating that the availability of nutrients in the soil influenced the expression of these effects; due to the above, they were analyzed within each of the fertilization treatments. In the fertilization treatment, no statistical significance (p> 0.05) for any of the evaluated effects was observed, whereas in the treatment of non-fertilization there were significant reciprocal and maternal effects (p< 0.05) for DFH6, and there was no significance to non-maternal effects (Table 6). The above indicates that some of the evaluated crosses showed differences in the DFH6 variable between the direct and reciprocal combinations; and these differences were due only to maternal effects, i.e., the no preference of S. frugiperda in these crosses depended on genes located in extranuclear DNA (Sánchez-Sánchez et al., 2010), but were only expressed in the non fertilization treatment.

GL= grados libertad; SC= suma de cuadrados; CM= cuadrados medios; ACG= aptitud combinatoria general; ACE= aptitud combinatoria especifíca; REC= efectos recíprocos; MAT= efectos maternos; NoM= efectos no maternos; CV= coeficiente de variación.

Table 6 Results of diallel analysis for leaf damage by S. frugiperda in the ligulate sixth leaf stage in maize cultivars derived from germplasm native of Tamaulipas within each fertilization treatment.

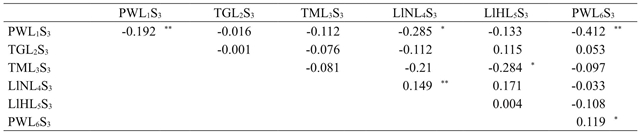

In the non fertilization treatment, significant reciprocal effects were observed for PWL1S3×LlNL4S3, TML3S3×LlHL5S3 and PWL1S3×PWL6S3 crosses (Table 7), which indicates differences in DFH6 between their respective direct and reciprocal crosses; the PWL1S3×LlNL4S3 and TML3S3×LlHL5S3 crosses did not show significance for the effects of specific combining ability (Table 7), the above is due to the significant reciprocal effects of these same crosses.

†= efectos maternos en el tratamiento de no fertilización se presentan en la diagonal; ††= efectos recíprocos en el tratamiento de no fertilización se presentan sobre la diagonal;* y **= diferente de cero con probabilidad de 0.05 y 0.01 respectivamente.

Table 7 Maternal and reciprocal effects for leaf damage by S. frugiperda in the sixth ligulate leaf stage in maize cultivars developed from germplasm native of Tamaulipas in the non fertilization treatment.

Thus, the PWL1S3×LlNL4S3 and TML3S3×LlHL5S3 averaged a DFH6 of 0.733 and 0.8 respectively, showing damage by S. frugiperda in less than 20% of foliar area of the plant, average preference of this insect of lower level compared to its reciprocal crosses, LlNL4S3×PWL1S3 and LlHL5S3×TML3S3 with DFH6 of 1.933 and 2.133 respectively, that is to say, a damage greater than 30% of its leaf area; when considering that the average DFH6 for PWL1S31 and LlNL4S3 lines was 1.333 and 2.2 respectively, while for TML3S3 and LlHL5S3 lines it was of 1.8 and 2.2 respectively, it can be inferred that the crossing of these lines favored the decreasing preference of S. frugiperda only in the PWL1S3×LlNL4S3 and TML3S3×LlHL5S3 direct crosses (Table 3).

Moreover, significant reciprocal effects for PWL1S3×PWL6S3 cross were found in the treatment of non-fertilization, where PWL1S3×PWL6S3 direct cross had a DFH6 average of 0.867 and the PWL6S3×PWL1S3 reciprocal cross was 2.267 (Table 3), the above indicates that only the PWL1S3×PWL6S3 direct cross had a negative specific combinatorial ability; therefore, this cross can be considered as an outstanding heterotic pattern for no preference of S. frugiperda and taking into account the significant reciprocal effects observed, it should be established what will maternal and paternal parents be (Cervantes et al., 2011) in a breeding program by hybridization in which this cross is included.

In this sense, the TGL2S3×LlHL5S3 cross had significant combinatorial specific ability and negative for DFH6 and did not show significance for reciprocal effects (Table 7), so it can be interpreted that this cross is an important heterotic pattern for resistance of non preference of S. frugiperda, regardless of the order of its parents; however, if is taking into account the high average of DFH6 of TGL2S3 and LlHL5S3 parents, 2.333 and 2.2 respectively (Table 3), which means more than 30% of leaf area with damage by this insect; according to Cervantes et al. (2011), it would be necessary to decrease the preference of S. frugiperda by a recurrent selection process, within each of the lines, for its later inclusion in a breeding program by hybridization.

Moreover, it is important to note that non preference resistance of S. frugiperda, is only a single character to be considered in a breeding program; therefore these lines could be integrated to a process of improvement by archetype of good size, precocity and high grain yield, characteristics that the progenitors and commercial hybrids must have for the agricultural regions of Tamaulipas.

There was significance in the maternal effects×fertilization treatment interaction, only significant maternal effects were observed in the non-fertilization treatment (Table 6), where the LlNL4S3 and PWL6S3 lines stand out with significant and positive maternal effects (Table 7) which indicates that the average levels of preference of S. frugiperda of all crosses in which these lines participated as maternal progenitors are greater in relation to the preference levels shown by the crosses in which these lines functioned as paternal progenitors. On the contrary, the PWL1S3 line showed significant and negative maternal effects (Table 7).

Therefore, the average preference level in the crosses in which this line participated as a maternal progenitor was lower compared to the crosses in which the same line was a paternal progenitor; which led to the significance of the reciprocal effects in the PWL1S3×PWL6S3 cross (Table 7). This significant effect on DFH6 by S. frugiperda on these crosses, indicates that the genes responsible for the features that provide resistance for non-preference are expressed in greater magnitude when inherited by the maternal parent (Espinosa et al., 2009), and this phenomenon is not consistent with the Mendelian principle, which implies the equal expression of the genes in the progeny, regardless of whether they are inherited by the paternal or maternal progenitor (Sokolov, 2006).

Conclussions

Genetic variability exists and high non-preference levels of S. frugiperda in evaluated maize germplasm, but its expression was influenced by fertilization treatments in which it was evaluated.

The non-additive variance showed greater importance for DFH6 and the TGL2S3×LlHL5S3 and PWL1S3×PWL6S3 crosses showed the greatest effects of specific combining ability.

PWL1S3×PWL6S3 cross showed reciprocal effects for DFH6 and these were cause of significant maternal effects of the PWL1S3 parental line.

Literatura citada

Altieri, M. A. y Nicholls, C. 2006. Optimizando el manejo agroecológico de plagas a través de la salud del suelo.Agroecología. 1:29-36. [ Links ]

Ávila, P. M. A.; Rodríguez, H. S. A.; Vázquez, B. M. E.; Borrego, E. F.;Lozano del R, A. J. y López, B. A. 2009. Aptitud combinatoria y efectos recíprocos en líneas endogámicas de maíz de valles altos del centro de México. Agric. Téc. Méx. 3:285-293. [ Links ]

Badii, M. H. y Garza, A. V. 2007. Resistencia en insectos, plantas y microorganismos. CULCyT. 18:9-25. [ Links ]

Bänziger, M.; Edmeades, G. O.; Beck, D. y Bellon, M. 2012.Mejoramiento para aumentar la tolerancia a sequía y a deficiencia de nitrógeno en el maíz: De la teoría a la práctica. CIMMYT. El Batán, Estado de México. 61 p. [ Links ]

Bruns, H. A. and Abbas, H. K. 2006. Planting date effects on Bt and non-Bt corn in the Mid-South USA. Agron. J. 98:100-106. [ Links ]

Casmuz, A.; Juárez, M. L.; Socías, M. G.; Murúa, M. G.; Prieto, S.;Medina, S.; Willink, E. y Gastaminza, G. 2010. Revisión de los hospederos del gusano cogollero del maíz, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Rev. Soc. Entomol.Argent. 69:209-231. [ Links ]

Castro, N. S.; López, S. J. A.; Pecina, M. J. A.; Mendoza, C. M. C. y Reyes, M. C. A. 2013. Exploración de germoplasma nativo de maíz en el centro y sur de Tamaulipas. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 4:645-653. [ Links ]

Cervantes, O. F.; García, S. G.; Carballo, C. A.; Bergvinson, D.; Crossa,J. L.; Mendoza, E. M.; Andrio, E. E.; Rivera, R. J. G. y Moreno,M. E. 2011. Estimación de efectos genéticos relacionados con el vigor de la semilla y de la plántula en maíces tropicales mexicanos. Φhyton. 80:19-26. [ Links ]

De la Cruz, L. E.; Castañón, N. G.; Brito, M. N. P.; Gómez, V. A.; Robledo,T. V. y Lozano, R. A. J. 2010. Heterosis y aptitud combinatoria de poblaciones de maíz tropical. Фhyton. 79:11-17. [ Links ]

Díaz, G. A. F. 2015. El juicio de los transgénicos. Orbis, Rev. Científ.Cienc. Hum. 10:17-30. [ Links ]

Espinosa, T. E.; Mendoza, C. M. C.; Castillo, G. F.; Ortiz, C. J.; Delgado,A. A. y Carrillo, S. A. 2009. Acumulación de antocianinas en pericarpio y aleurona del grano y sus componentes genéticos en poblaciones criollas de maíz pigmentado. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 32:303-309. [ Links ]

Fernández, J. L. y Expósito, I. E. 2000. Nuevo método para el muestreo de Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) en el cultivo del maíz en Cuba. Centro Agrícola. 27:32-38. [ Links ]

Fernández, N. E. N. 1991. Mejoramiento por resistencia a los principales virus de la papa. Rev. Latinoam. Papa 4:1-21. [ Links ]

Granados, G. 2001. Manejo integrado de plagas. In: el maíz en los trópicos: mejoramiento y producción. Paliwal, R. L.; Granados,G.; Lafitte, H. R.; Violic, A. D. y Marathée, J. P. (Eds.). FAO.Italia. 295-314 pp. [ Links ]

Granados, G. y Paliwal, R. L. 2001. Mejoramiento para resistencia a los insectos. In: el maíz en los trópicos: mejoramiento y producción.Paliwal, R. L.; Granados, G.; Lafitte, H. R.; Violic, A. D. y Marathée, J. P. (Eds.). FAO. Italia. 179-197 pp. [ Links ]

Griffing, B. 1956. Concept of general and specific combining ability in relation to diallel crossing systems. Aust. J. Biol. Sci. 9:463-493. [ Links ]

Guillen, de la C. P.; de la Cruz, L. E.; Castañon, N. G.; Osorio, O. R.;Brito, M. N. P.; Lozano, R. A. y López, N. U. 2009. Aptitud combinatoria general y específica de germoplasma tropical de maíz. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyt. 10:101-107. [ Links ]

Massieu, T. Y. C. 2009. Cultivos y alimentos transgénicos en México. El debate, los actores y las fuerzas sociopolíticas. Argumentos.22:217-243. [ Links ]

Moreno, F. L. P. 2009. Respuesta de las plantas al estrés por déficit hídrico.Una revisión. Agro. Colom. 27:179-191. [ Links ]

Murúa, M. G.; Molina, O. J. and Coviella, C. 2006. Population dynamics of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera:Noctuidae) and its parasitoids in Northwestern Argentina. Fla. Entomol. 89:175-182. [ Links ]

Negrete, B. F. y Morales, A. J. 2003. El gusano cogollero del maíz(Spodoptera frugiperda Smith). Corpoica Ecorregión Caribe Centro de Investigación Turipaná. Colombia. 26 p. [ Links ]

Nexticapan, G. A.; Magdub, M. A.; Vergara, Y. S.; Martín, M. R. y Larqué,S. A. 2009. Fluctuación poblacional y daños causados por gusano cogollero (Spodoptera frugiperda JE Smith) en maíz cultivado en el sistema de producción continúa afectado por el huracán Isidoro. UCiencia. 25:273-277. [ Links ]

Pecina, M. J. A.; Mendoza, C. M. C.; López, S. J. A.; Castillo, G. F.;Mendoza, R. M. y Ortiz, C. J. 2011. Rendimiento de grano y sus componentes en maíces nativos de Tamaulipas evaluados en ambientes contrastantes. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 34:85-92. [ Links ]

Reséndiz, R. Z.; López, S. J. A.; Osorio, H. E.; Estrada, D. B.; Pecina, M.J. A.; Mendoza, C. M. C. y Reyes, M. C. A. 2016. Importancia de la resistencia del maíz nativo al ataque de larvas de lepidópteros.Tema de Cienc. y Tecnol. 20:3-14. [ Links ]

Saldúa, V. L. y Castro, A. 2011. Expresión de la antibiosis y de la antixenosis contra el pulgón negro de los cereales (Sipha maydis) en cultivares comerciales de trigos. Rev. Fac. Agron.La Plata. 110:1-11. [ Links ]

Sánchez, S. H.; González, H. V. A.; Cruz, P. A. B.; Pérez, G. M.; Gutiérrez, E. M. A.; Gardea, B. A. A.; Gómez, L. M. Á. 2010. Herencia de capsaicinoides en chile manzano (Capsicum pubescens R.y P.). Agrociencia. 44:655-665. [ Links ]

Sokolov, V. A. 2006. Imprinting in plants. Russ. J. Genet. 42:1043-1052. [ Links ]

Vanegas, A. H.; De León, C. y Narro, L. L. 2007. Análisis genético de la tolerancia a Cercospora spp. en líneas endogámicas de maíz tropical. Agrociencia. 41:35-43. [ Links ]

Vivanco, J. M.; Cosio, E.; Loyola, V. V. M. y Flores, H. E. 2005.Mecanismos químicos de defensa en las plantas. Inv. y Cien.2:68-75. [ Links ]

Zhang, Y.; Kang, M. S. and Lamkey, K. R. 2005. DIALLEL-SAS05: acomprehensive program for griffing’s and Gardner-Eberhart analyses. Agron. J. 97:1097-1106. [ Links ]

Received: April 2017; Accepted: July 2017

texto en

texto en