Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.7 spe 15 Texcoco jun./ago. 2016

Articles

Technology information and communication as a source of knowledge in the rural sector

1Centro de Investigaciones Económicas Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agroindustria y la Agricultura Mundial (CIESTAAM)-Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Carretera México-Texcoco km 38.5, 56230. Chapingo, Estado de México. México. (jjimenezc@ciestaam.edu.mx).

2West Virginia State University, Gus R. Douglass Land-Grant Institute 131 Ferrell Hall, P. O. Box 1000. (toledoju@wvstateu.edu).

3Departamento de Enseñanza e Investigación en Zootecnia- Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Carretera México-Texcoco km. 38.5, 56230. Chapingo, Estado de México. México. (garanda@gmail.com).

This research analyzes the use of information technology and communication (TIC) as a means of access to information in rural producers. Three aspects were considered: (i) differentiating information sources according to the percentage of information provided by each actor; (ii) analyzing the information needs for technical-productive area of the producers; and (iii) comparing the factors of exclusion among producers and do not use TIC tools. To obtain data, during 2014, THE 67 surveys were applied in eight municipalities in the Northern and Costa Chica region of the state of Guerrero. The information was submitted to an analysis of innovation networks to a variety of sources analysis by Simpson index and a two-stage cluster analysis. The results showed that TICs contribute 3% of the information used by producers. A correlation coefficient of 0.8 between the number of sources and consulted media and the use of TIC was found. The adoption of TIC is associated with age, education level, the size of the farm, and the years of experience in the business. It is concluded that TICs contribute to process information and have potential in providing information on rural producers.

Keywords: cluster analysis; innovation network; sources of information

Esta investigación analiza el uso de las tecnologías de la información y comunicación (TIC) como medio de acceso a información en productores rurales. Se consideraron tres aspectos: (i) diferenciando las fuentes de información de acuerdo al porcentaje de información proporcionada por cada actor; (ii) analizando las necesidades de información por área técnico-productiva de los productores; y (iii) comparando los factores de exclusión entre productores que utilizan y no utilizan las herramientas TIC. Para la obtención de datos, durante 2014 se aplicaron 67 encuestas en ocho municipios de la Región Norte y Costa Chica del estado de Guerrero. La información se sometió a un análisis de redes de innovación, a un análisis de diversidad de fuentes mediante el índice de Simpson y a un análisis de conglomerados bietápicos. Los resultados mostraron que las TIC contribuyen con el 3% de la información usada por los productores. Se encontró un coeficiente de correlación de 0.8 entre el número de fuentes y medios consultados y el uso de las TIC. La adopción de las TIC está asociada a la edad, el nivel de escolaridad, el tamaño de la explotación, y a los años de experiencia en la actividad. Se concluye que las TIC contribuyen al proceso de información y tienen potencial en el aporte de información en los productores rurales.

Palabras clave: análisis de conglomerados; fuentes de información; red de innovación

Introduction

The technologies of information and communication technologies (TIC) according to Bosch (2012) enhance social and cultural practices of people around the world, accelerate cognitive both individuals kills and collective, they have changed the way we communicate and get information . According to INEGI (2014) the internet in homes of Mexico increased 4.7% from 26% in 2013 to 30.7% in 2014. This reflects a greater number of people benefiting from the use of TIC in Mexico.

According to Rodrigues (2012) the TIC is a tool for access and organization of knowledge available to farmers. Some authors (Lin and Heffernan, 2010; Ali, 2011; Castleton, 2011; Saghir et al., 2013) emphasize that TIC in the agricultural sector reduce costs in obtaining information, increase income of rural producers, contribute networking and collaborative business partnerships, facilitate learning and training improving productivity and reducing risks. Despite these advantages of TICs for the agricultural sector, Hopkins (2012) notes that studies on the impact of TIC in the agricultural sector are still limited.

In countries like India, China or Pakistan according to Saghir et al. (2013), Yang et al. (2011) and Ali (2011) the use of TIC has been raised for obtaining information on specific productive sectors, such as goats, sheep and beef production, even smaller producers oriented production scale and low education levels.

In Latin America there are different forms of linkage between TIC and the agricultural sector; in Costa Rica Platform Technology, Information and Communication Agriculture and Rural (Platicar, 2011) created by the National Institute of Innovation and Transfer of Agricultural Technology (INTA) knowledge exchange between farmers, extension agents and researchers to solve specific problems of the sector; in Chile the project "Yo agricultor" (2009) funded by the Foundation for Agrarian Innovation (FIA) in conjunction with the Inter- American Development Bank (IDB) seeks solutions using TICs to improve access to and use of relevant information for decision decisions of producers of specific regions and clusters of agricultural production and livestock character; in the Salvador the platform "Agromóvil" (2014) character private, provides access to pricing information and market climate, buy or sell products or services and technical advice. These initiatives linking despite being recent, are now a tool that empowers producers.

In Mexico there have also been initiatives linking TIC and agriculture, as in the case of MasAgro Mobile, an information service prices, weather conditions and sustainable farming practices transmitted to cellular users, technicians and producers mainly through SMS text messages. This initiative created by CIMMYT and SAGARPA, seeks to increase the availability of information, build capacity and transfer technologies to small and medium producers of corn and wheat. However, the service is unidirectional and not delves into the priority needs of users, unlike the Platicar platform or project Yo agricultor.

Based on the positive correlation between competitiveness and the development of the TIC sector globally exposed by Palacios et al. (2013), the country's National Digital Strategy was implemented, which is an initiative that aligns objectives, policies and actions of actors in society to extend the use and development of TIC in Mexico and contribute to reducing the competitive lag inter sectoral nation in the world and with its Latin American peers.

Moreover, the problem of agriculture is its low growth caused by various reasons such activities are: i) the low development of technical-productive and entrepreneurial skills; ii) insufficient technological innovation in the rural sector; iii) low levels of productivity of rural economic units; iv) limited access to agricultural markets access; v) insufficient funding for agricultural activities; vi) patrimony phyto-zoo-sanitary unfavorable; and vii) the high level of risk of agricultural activity (SAGARPA and FAO, 2014). In these cases the subject is aligned with the low development of technical- productive and entrepreneurial capabilities (Figure 1).

Delving into the causes of low capacity, according to SAGARPA and FAO (2014) the heads of agricultural production units in Mexico have a low level of education, as 20.9% did not attend any school grade and 56.8% have some degree primary education, for this reason, low levels of formal education are presented as a factor limiting the development of human capital in the sector and its population and its technological, productive and entrepreneurial skills.

Regarding the low access to economic information, according to SAGARPA and FAO (2014) of the total (108 597) of UPA who received training, only 14.5% (15 792) was on issues related to management and marketing. This limits the access and knowledge of market opportunities.

Finally the low technical and production information in accordance with (Roldan, 2013) only 2.1% of the UPA had access to training and technical assistance. This limitation according to some authors (Suárez and López, 1996; Aranda etal., 2009; AMEG, 2010) has led to an efficiency of only 50% in the production units focused on the production of cattle.

While these three elements are not the only determinants of the low level of technical-productive and entrepreneurial skills, yes they are a necessary for them to develop condition, TIC is a tool that plays an important role in reducing the deficit of information, improving learning and decision-making (Rodrígues, 2012 and Ali, 2011). In this study the use of TIC is discussed as a means of access to information on three aspects: (1) sources covering the information needs differ; (2) it is considered the association between the number of sources consulted and the use of TIC; and (3) the exclusion factors in cattle producers.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in the state of Guerrero from june to july 2014. The approach to producers of cattle was carried out through the Ministry of Rural Development (SEDER) state, who operates under the model Rancher Validation Group and Technology Transfer (GGAVATT). This involves the integration and coordination of a group of 15 to 20 producers who are given technical advice and support of research centers through a technician (Aguilar et al., 2002). In the year 2014 the 70 groups GGAVATT distributed statewide were recorded for the data survey was designed and by a non-probability sampling was applied in 8 groups distributed in five municipalities and two regions, obtaining a total of 67 surveys, 46 in the Costa Chica region and 21 in the North region.

Data extraction for a survey that was divided into five sections designed: (i) identification of the producer; (ii) equipment in the field of TIC; (iii) structure of the herd; (iv) needs and sources of information (The information sources were preset in order to facilitate the extraction of data); and (v) the importance of the production unit for the producer. The survey was composed of 37 questions, of which 35 were closed and 2 open.

The data obtained were subjected to an analysis of innovation networks to identify the main sources of information on the network, by the degree of input; i.e. the frequency with which it was referred to the source. Producer groups were formed taking into account the number of sources that consultation.

An index of diversity of sources or Simpson index was calculated. This commonly is used to determine the diversity of plant community (Bouza and Covarrubias, 2005). However, this research was used to calculate the differences between producers about the number of sources, under the premise that a greater diversity of sources of information, greater producer's ability to overcome unfavorable circumstances in its production unit and indirectly take better decisions. The following formula (Mostacedo and Frederiksen, 2000) was used to calculate the index Simpson:

Where: S= Simpson index; ni= number of information sources consulted by the i-th producer and N= total number of information sources.

To analyze the type of information provided by the source consulted, technical categories were formed based on the following questions (Table 1).

The Pearson correlation coefficient was also calculated to show the relationship between the use of TIC and the number of realized practices. The practices were established according to several authors (Farías, 2002; Marte and Villeda, 2009) indicate as good production practices of cattle to be made to improve their development.

Finally, an analysis of two-stage cluster or in two phases, which is an exploratory tool designed to reveal natural groupings of a set of data was performed, also called cluster, so that individuals considered similar according to the variables are assigned to the same cluster (Pérez, 2008). With this analysis the similarity between producers using TIC as a means of access to information and those who do not use was found.

Results and discussion

The results generated from the analysis of innovation networks showed that TIC s contribute 3% of the sources of information used by farmers in beef production and other popular sources were direct private veterinarians (15%) consultation, GGAVATT technical (27%) and communication with other producers (42%), it is observed in Figure 2 where the larger the node indicates that it is consulted.

Figure 2. Actors and sources of information on livestock innovation network in the state of Guerrero.

With the analysis of innovation networks five strata of producers taking as a grouping variable number of sources, then describes each of the strata were also generated:

Stratum I: composed of producers who consulted one or two sources, in this stratum 90% of the information obtained came from communication with other producers. Here it was observed that producers make the smallest percentage of practices (Table 2).

Stratum II: composed of producers who consulted three sources of information, it is noted that the main source was another producer (53%), followed by technical GGAVATT (28%) and private veterinary (10%). From this layer the use of TIC (2%) as a means of obtaining information appears. It was also observed that this stratum increased by 18% the number of practices carried out over the previous.

Stratum III: composed of producers who consulted four sources, 38% of the information obtained came from another producer, 29% of technical GGAVATT, 18% of the private veterinarian and 7% of cattle buyer. The use of TIC in this stratum decreased to 1% and the number of practices by this stratum remained similar to the previous. Although the information obtained came from a greater diversity of sources (Table 2).

Stratum IV: composed of producers who consulted five sources, 62% of the information obtained came from communication with another producer and technical GGAVATT, 17% of the private veterinarian, 8% of cattle buyer and TIC had a significance of 5% (Table 2). Similar results are reported by Ali (2011) in a study in India with 342 cattle where 60% of the information was obtained from another producer.

Stratum V: composed of producers who consulted six sources, 63% of the network information obtained came from communication with another producer and technical GGAVATT, 12% of the private veterinarian, and 13% TIC as sources of information.

The difference between strata seen in the increased rate of Simpson this can be explained by the increase in the sources of information. Also the number of practices also increased responding to perform a correlation coefficient of 0.85. The use of TIC is also linked to a greater number of sources, which denotes the use of these devices as a secondary source.

To explain the type of information that producers are consulted by TIC in the Table 3 was structured in which consultation races and news are the categories in which TIC had higher use as a secondary source within this network. In the categories of input prices-food and vaccines, TIC is used to a lesser extent, perhaps because pricing information according to Castleton (2011) is governed by local markets and domestic prices are only a reference to the producer.

The problem of low access to technical and production information matches the results found (Table 3), which is reflected in the categories with the lowest percentage of completion, which are: management, reproduction and input prices-feeding, these categories are essential in the development of the production unit and should be increased. This creates an opportunity for the use of TIC as a tool to assist in increasing access to productive technical information concerning the deficit identified categories.

The Table 3 also shows the relevance of the sources and means consultative learned the information requested by respondents producers. The importance of sources or means is characterized by the type of information provided, this is how the private veterinarian was an important source in the area of prices and vaccines to apply covering 37% of the information, in the case of technical GGAVATT highlights in the categories of reproduction and handling. Despite the variety of media and sources has the greatest weight in all categories is that of other producers, revealing that the information within this network is redundant and low impact on production units.

The presence of TIC as a means of access to information is not dominant in any category; however, their presence reflects exploring new horizons by producers. Castleton (2011) in a study in Montevideo highlights that who has access to the Internet and a computer can learn more about prices, the state of the markets, bring traceability, observe the auctions on television or the Internet and in that sense have more opportunities but it is not essential to use TIC.

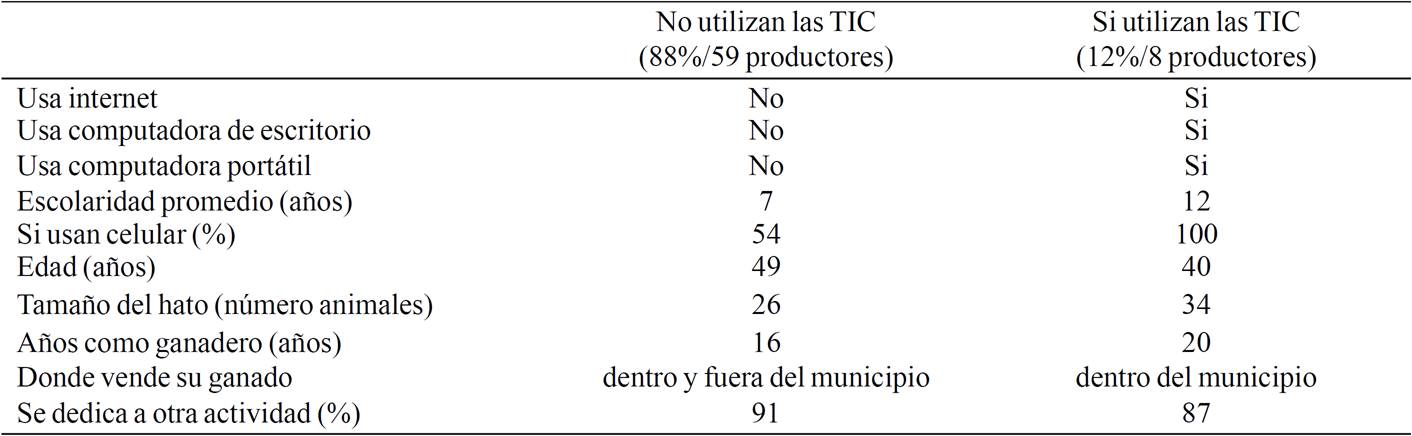

Finally the results generated from cluster analysis (Table 4) showed proficiency in the differences between producers using TIC (internet, laptop, desktop computer and cell) for information related to your unit production and those who do not use this resource. Producers using TIC, have on average more years of schooling, larger herd and more experience in livestock. These findings are consistent with several authors (Meera et al., 2004; Saravanan et al., 2009; Ali, 2011; Castleton, 2011; Rodrígues, 2012; Tena et al., 2015) who point out that the adoption of TIC is sensitive variables such as location, size and income level of farms, market access, insertion in the production chain, technological level, age, education of producers, approach to the production unit and years dedicated to the activity.

Intro the TIC within the cell have a widespread dissemination among producers, this can be explained by increased access to connectivity, but the use of these devices is still limited to messaging and calls.

Conclusions

The TICs are used as a secondary source by producers who consult more than three sources of information on the network, not only those that comply with the information obtained from the neighboring producer, technical GGAVATT or private veterinarian. Such producers are those who made more practical and have higher rates of Simpson.

The TIC not dominate as a source of information on any technical-productive category, such as information from another producer, however, are present and complement some categories, especially those involving information visual, such as search livestock breeds and news the sector. They are also used in more complex categories such as breeding and feeding.

It was identified that the main factors of exclusion for the use and adoption of TIC in livestock were educational level, herd size, age of the producer, years of experience in livestock and market access. Moreover, despite regional developments and initiatives in the country, connectivity remains a central obstacle to the diffusion, adoption and use of TIC. They are also barriers from the absence of boost (competitive pressure, demands of suppliers and buyers) for the transformation of traditional systems in more TIC intensive modalities.

The TIC facilitate collaboration between producers of cattle, improving the availability and handling of new information useful for the production unit. That's why to contribute to the development of technical-productive and entrepreneurial skills, strategies must be implemented TIC use two-way, allowing meet the priority needs of the producer.

Literatura citada

Agromóvil. 2014. Agromovil. http://www.agromovil.org/# (consultado noviembre, 2014). [ Links ]

Aguilar, B. U.; Amaro, G. R.; Bueno, D. H. M.; Chagoya, F. J. L.; Koppel, R. E. T. y Ortíz, O. G. A. 2002. Marco teórico conceptual del modelo GGAVATT. In: manual para la formación de capacitadores modelo GGAVATT. Saldaña, A. R. (Coord.). Zacatepec, Morelos, México. 40-46 pp. [ Links ]

Ali, J. 2011. Use of quality information for decision-making among livestock farmers: role of information and communication technology. Livestock Res. Rural Develop. 23(3):1-6. [ Links ]

Aranda, O. G.; García, O. J. C.; Monzon, A. J. M.; Hernández, G. A. y Ortega, N. G. C. 2009. Importancia de la producción de carne de res en México. México. Extensión al campo. 2(2):19-22. [ Links ]

AMEG. 2010. Ganado bovino productor de carne. México. SAGARPA- SENASICA. D. F., México. 1-54 pp. [ Links ]

Bosch, M. 2012. Un futuro regional en construcción. In: TIC y agricultura. Palacios, L. (Ed.). CEPAL. Newsletter eLAC No.18. Santiago, Chile. 6-12 pp. [ Links ]

Bouza, C. N. y Covarrubias, D. 2005. Estimación del índice de diversidad de Simpson en m sitios de muestreo. Rev. Inves. Oper. 2(26):187-197. [ Links ]

Castleton, A. 2011. TIC y ganadería: exclusión de los pequeños productores a partir de los remates de ganado por pantalla. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad de la República. 1-31 pp. [ Links ]

Farías, A. J. R. 2002. Manual de producción de bovinos. Subsecretaría de Fomento y Desarrollo Agropecuario del Estado de Nuevo León. Primera edición. Monterrey, Nuevo León, México. 50-150 pp. [ Links ]

Hopkins, R. 2012. El impacto de las TIC en la agricultura es enorme. In: TIC y agricultura. Palacios, L. (Ed.). CEPAL. Newsletter eLAC No.18. Santiago, Chile. 1-12 pp. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2009. Censo Agrícola, Ganadero y Forestal 2007. http://www.inegi.org.mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/Agro/ca2007/Resultados_Agricola/. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2014. Estadísticas a propósito del día mundial de internet. http://www.inegi.org.mx/inegi/contenidos/espanol/prensa/contenidos/estadisticas/2014/internet0.pdf. [ Links ]

Lin, Y. and Heffernan, C. 2010. Creating the livestock guru: icts to enhance livestock-related knowledge among poor households in orissa, India. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 42(7):1353-1361. [ Links ]

Marte, R. y Villeda, E. D. 2009. Manual de buenas prácticas en explotaciones ganaderas de carne bovina. IICA-Programa Nacional de Desarrollo Agroalimentario. Tegucigalpa, Honduras. 30-70 pp. [ Links ]

Meera, S. N.; Jhamtani, A. and Rao, D. U. M. 2004. Information and communication technology in agricultural development: a comparative analysis of three projects from India. Network Paper. 135:1-14. [ Links ]

Mostacedo, B. y Fredericksen, T. S. 2000. Manual de métodos básicos de muestreo y análisis en ecología vegetal. Proyecto de manejo forestal sostenible. Editora El País. Primera edición. Santa Cruz, Bolivia. 45-47 pp. [ Links ]

Palacios, J.; Flores-Roux, E. y García, Z. A. 2013. Diagnóstico del sector TIC en México Conectividad e inclusión social para la mejora de la productividad y el crecimiento económico. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID). Documento de debate # IDB-DP-235. Washington D.C., Estados Unidos. 10-30 pp. [ Links ]

Pérez, L. C. 2008. Técnicas de análisis multivariante de datos. Pearson Educación. Segunda edición. Madrid, España. 10-65 pp. [ Links ]

Platicar. (Plataforma de Tecnología, Información y Comunicación Agropecuaria y Rural). 2011. Plataforma Platicar. http://www.inta.go.cr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=97&Itemid=76. [ Links ]

Rodrígues, M. 2012. Las TIC como herramienta para la superación de asimetrías. In: TIC y agricultura. Palacios, L. (Ed.). CEPAL. Newsletter eLAC No.18. Santiago, Chile. 1-12 pp. [ Links ]

Saghir, A.; Chaudhary, K. M.; Muhammad, S. and Maan, A. A. 2013. Role of ICTs in bridging the gender gap of information regarding livestock production technologies. J. Animal Plant Sci. 23(3):929-933. [ Links ]

Saravanan R.; Raja, P. and Tayeng, S. 2009. Information input pattern and information need of tribal farmers of Arunachal Pradesh. Ind. J. Ext. Ed. 45(1-2):51-54. [ Links ]

SAGARPA y FAO. 2014. Diagnóstico del sector rural y pesquero: identificación de la problemática del sector agropecuario y pesquero de México. In: diagnóstico del sector rural y pesquero de México. Gónzalez, C. A. (Coord.). Danda impresores. Primera edición. D. F., México. 6-55 pp. [ Links ]

Suárez, D. H. y López, T. Q. 1996. La ganadería bovina productora de carne en México. Departamento de Zootecnia de la Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Texcoco, Estado de Mexico. 1-16 pp. [ Links ]

Tena, G. P. A.; Rendón, M. R.; Sangerman-Jarquín, D. M. y Castillo, C. J. G. 2015. Extensionismo agrícola en el uso de tecnologías de la información y comunicación (TIC) en Chiapas y Oaxaca. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 6(1):175-186. [ Links ]

Yang, Y.; He, T. and Zhang, Y. 2011. Mobile phones of 3g era in small and medium-sized agricultural production and application prospect. In: computer and computing technologies in agriculture IV. Daoliang, L.; Yande, L. and Yingyi, C. (Eds.). School Of Mechanical And Electronical Engineering, East China Jiaotong University. Nanchang, Jiangxi, China. 375-378 pp. [ Links ]

Yo agricultor. 2009. Yo agricultor. http://www.yoagricultor.cl/yoagricultor/index.php?errorcode=4. [ Links ]

Received: December 2015; Accepted: March 2016

texto en

texto en