Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.5 spe 8 Texcoco 2014

Investigation notes

Fungal diversity in oat seeds from the Central Valley of Mexico

1Departamento de Parasitología Agrícola-Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Carretera México-Texcoco km 38.5, C. P. 56230, Estado de México, México (lsantos@correo.chapingo.mx).

2Campo Experimental Valle de México, INIFAP. Carretera Los Reyes-Texcoco km 13.5, Coatlinchán, Texcoco, Estado de México. C. P. 56250 Tel: 01 595 9212715. Ext. 161. (villasenor.hector@inifap.gob.mx; rodriguez.maria@inifap.gob.mx).

3Fitopatología, Colegio de Postgraduados. Carretera México-Texcoco km 36.5, Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México. C. P. 56230 Tel. 01 595 9520200. Ext. 1614. (elizabeth.garcia@colpos.mx; jmtovar@colpos.mx).

The aim of this study was to determine the diversity and incidence of fungal pathogens and saprophytes present in oat seed (Avena sativa L.) obtained from Ágata, Chihuahua and Turquesa cultivars, in nine localities in the central valley of Mexico during the spring-summer 2009 and 2010 crop cycles. Through the Freezing-blotter test, the following species of plant pathogenic fungi were obtained: Alternaria alternarina, A. cerealis, A. uredinis, Bipolaris hawaiiensis, B. sorokiniana, B. spicifera, B. victoriae, Diplodia sp., Drechslera avenacea, Fusarium avenaceum, F. oxysporum, F. poae, F. verticillioides, Phoma sp. and Rhizoctonia solani. While, the saprophytic fungi found were: Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus niger, Cladosporium sp., Chaetomium sp., Coniothyrium sp., Epicoccum sp., Gonatobotrys sp., Graphium sp., Nigrospora sp., Stemphylium sp. and Torula sp. The overall fungal incidence was higher in the Chihuahua variety, followed by Ágata and Turquesa. In general, seeds from the 2009 cycle showed a higher fungal incidence.

Keywords: Avena sativa; Alternaria; Bipolaris; Diplodia; Drechslera; Fusarium; Phoma

El objetivo del presente estudio fue determinar la diversidad e incidencia de hongos fitopatógenos y saprofitos presentes en semilla de avena (Avena sativa L.) obtenida de los cultivares Ágata, Chihuahua y Turquesa, en nueve localidades del valle central de México, durante los ciclos de cultivo primavera-verano 2009 y 2010. Mediante la prueba de Freezing-blotter, se obtuvieron las siguientes especies de hongos fitopatógenos: Alternaría alternarina, A. cerealis, A. uredinis, Bipolaris hawaiiensis, B. sorokiniana, B. spicifera, B. victoriae,Diplodia sp., Drechsleraavenacea,Fusarium avenaceum, F. oxysporum, F. poae, F. verticillioides, Phoma sp. y Rhizoctoniasolani. Mientras que, los hongos saprófitos encontrados fueron: Alternaria alternata, Aspergillus niger, Cladosporium sp., Chaetomium sp., Coniothyrium sp., Epicoccum sp., Gonatobotrys sp., Graphium sp., Nigrospora sp., Stemphylium sp. y Torula sp. La incidencia total de hongos fue mayor en la variedad Chihuahua, seguida por Ágata y Turquesa. En general, las semillas del ciclo 2009 mostraron una mayor incidencia de hongos.

Palabras clave: Avena sativa; Alternaria; Bipolaris; Diplodia; Drechslera; Fusarium; Phoma

During the spring-summer 2009 and 2010 cycles, oat seeds from the Ágata, Chihuahua and Turquesa cultivars were collected in five localities in Tlaxcala (Teacalco, Nanacamilpa, Francisco I. Madero, Terrenate and Velazco) and four in the State of Mexico (Santa Lucía, Coatepec, Juchitepec and Chapingo). At each locality, 80 seeds were collected by cultivar, thus obtaining a total of 1 200 (2009 cycle) and 1 680 (2010 cycle). Induction of mycelial growth and fungal sporulation was performed by the Freezing-Blotter test described by Warham et al. (1998). The identification of fungal genera and species was performed using the taxonomic keys of Warham et al. (1998), Leslie and Summerell (2006), Simmons (2007), MAPA (2009), and Watanabe (2010).

The overall fungal incidence and the incidence of plant pathogens and saprophytes was evaluated. For the overall incidence, the presence/absence of fungi in seed was observed, by locality and cultivar. The means of data on overall fungal incidence and the incidence of fungal pathogens and saprophytes in percentage, were compared using the Tukey test, with p≥ 0.05, using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, 2003).

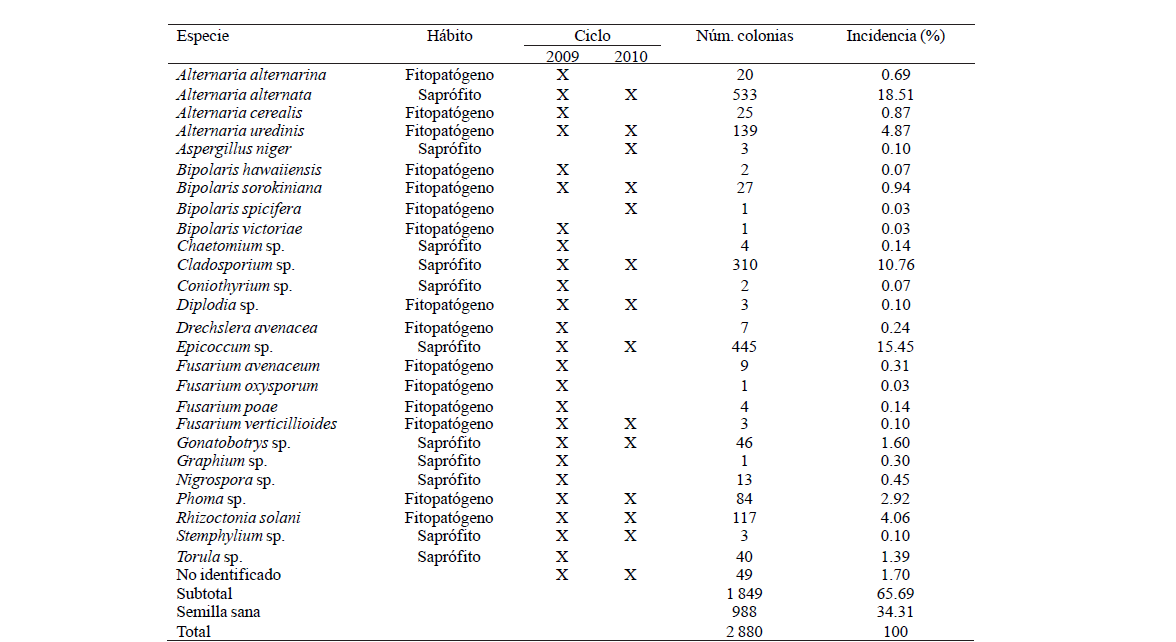

A total of 26 species of fungi were identified, of which 15 have been reported as plant pathogens and 11 as saprophytes. According to the number of colonies found, it was determined that 65.69% of seeds showed fungal incidence, and the remaining 34.31% belonged to healthy seed (Table 1).

Table 1 Fungal incidence in oat seeds of Ágata, Chihuahua and Turquesa cultivars obtained from different localities in the central valley of Mexico, during the spring-summer 2009 and 2010 cycles.

Alternaria uredinis, A. cerealis, A. alternarina, Rhizoctonia solani, Bipolaris spp. and Phoma sp. were found as the fungal pathogens with higher incidence, comprising 14.48%. While Cladosporium sp. and Epicoccum sp. were detected as the saprophytic fungi with the highest incidence, representing 26.21%. All oat seeds appeared healthy upon collection, however, when placed in a humid chamber by the Freezing-Bottler method, germination, growth and reproduction of fungal structures present in the seed was achieved.

Alternaria alternata was detected with the highest incidence (18.51%), coinciding with Neergaard (1977) and Kurowski (2009), who noted that A. alternata is present as a common contaminant in cereal seed. Moreover, the following plant pathogenic Alternaria species were found: A. alternarina, A. cerealis and A. uredinis consisting of 6.43% of the total incidence. This is consistent with Simmons (2007) who recorded these species causing leaf spots and blights in oats.

Rhizoctonia solani showed a significant incidence in this study, its pathogenic role in oat plants is very important, since this cereal is highly susceptible, and plants infected by this fungus have diamond-shaped lesions with a bronzed center and dark brown margins on pods of the lower leaves, and delayed maturity and in some cases causing plant death (Nyvall, 1999).

According to Zyllinsky (1984), Bipolaris spp. follow the rusts in importance as destructive pathogens of cereals worldwide. In this paper, Bipolaris sorokiniana, B. hawaiiensis, B. spicifera and B. victoriae colonies were obtained. Similarly, Bautista-Espinoza et al. (2011) recorded high incidence of B. sorokiniana and B. spicifera in wheat seeds obtained in the collection zone of this study.

In this investigation four Fusarium species were identified: F. avenaceum, F. poae, F. oxysporum and F. verticillioides. This fungus has been commonly isolated from Avena sativa seeds (Clear et al., 2000; Kurowski and Wysocka, 2009), A. fatua (Mortensen and Hsiao, 1987) and A. strigosa (Farias et al., 2002). Fusarium avenaceum proved to be the most frequent species, coinciding with indications from Clear et al. (2000) in his research on Fusarium spp. in oat seeds produced in Canada.

Drechslera avenacea was identified in seeds analyzed in this study consistent with reports from Lángaro et al. (2001), Silva et al. (2002) and Almeida and Reis (2009)), who found this species at high frequency in Avena sativa seeds. This is one of the main pathogens transmitted through oat seeds, besides being the causal agent of oat leaf blight (Lángaro et al., 2001; Carmona et al., 2004; Almeida and Reis, 2009).

Phoma sp. was obtained in low proportion in this investigation, as has been previously detected in A. strigosa seeds (Farias et al., 2002). However, Tariq et al. (2004) found a 46% incidence of Phoma sp. on different oat varieties produced in Pakistan, positioning this fungus currently as a pathogen of great importance in the production of this cereal.

Diplodia sp. was identified in seeds from two localities in Tlaxcala, Mexico, coinciding with Leyva-Mir et al. (2011), who reported this plant pathogen causing oat grain rot in the Chihuahua cultivar at the same place. Moreover, the high frequency of Cladosporium sp. in this study is consistent with that reported by Farias et al. (2002), who noted that this genus is one of the main saprophytes isolated from A. strigosa seeds.

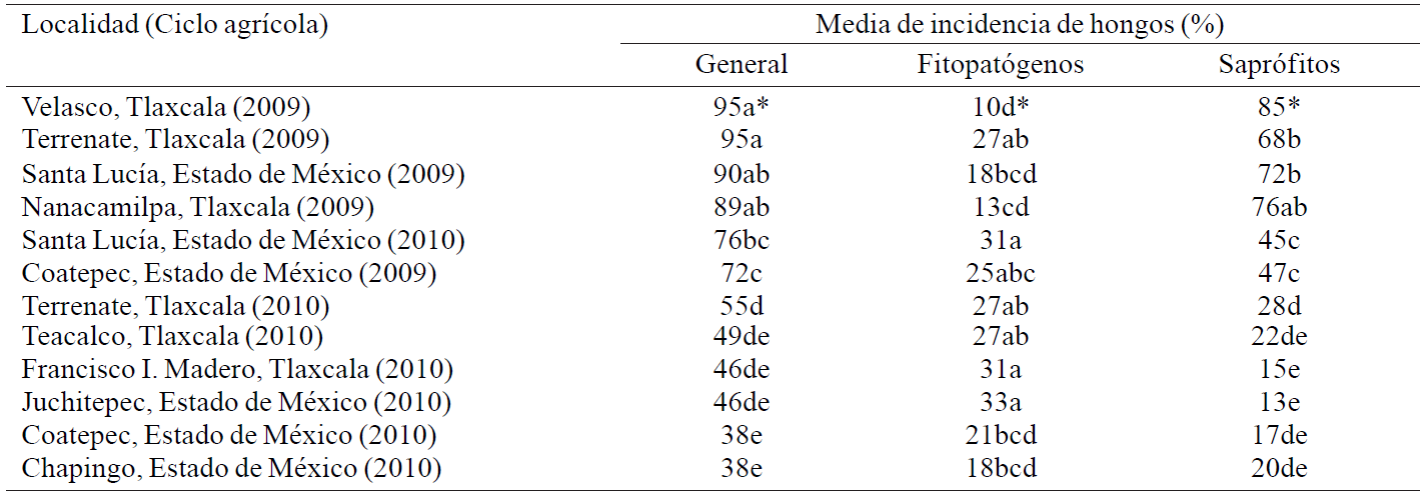

Table 2 shows the fungal incidence per locality. In general, it was found that samples from localities in the 2009 cycle showed a higher fungal incidence compared to the 2010 cycle. Moreover, significant differences was observed in overall fungal incidence, and incidence of pathogens and saprophytes between localities, indicating that each site showed different problems related to seed fungi. Zillinsky (1984) also found that the presence of diseases in cereals varies according to the environmental conditions of each region.

Table 2 Means comparison of the overall fungal incidence, and the incidence of pathogens and saprophytes by locality.

*Medias dentro de cada columna seguidas por la misma letra no difieren en la prueba de Tukey al 5% de probabilidad

The localities where samples were collected have a different annual rainfall, which probably had an impact on a different frequency of fungi in seeds, coinciding with Neergaard (1977), who mentioned that the presence of pathogens in seeds can fluctuate from one year to the next in the same region, due to variation in humidity conditions.

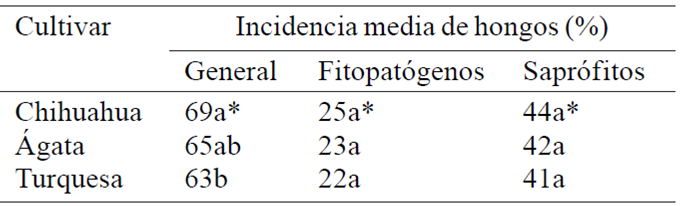

Results of the incidence of fungi per cultivar are shown in Table 3, indicating that the Chihuahua cultivar showed higher overall incidence followed by Ágata and Turquesa. This could be because the Chihuahua cultivar was released before the others, and it is highly susceptible to foliar diseases and stem rust (Puccinia graminis f. sp. avenae) (Jiménez, 1992). While the Ágata and Turquesa varieties which were released in 2009, express tolerance to the foliar disease complex caused by Drechslera avenacea, Septoria avenae f. sp. avenae and Colletotrichum graminicola, besides being moderately resistant to stem rust and crown rust (Puccinia coronata) (Villaseñor-Mir et al, 2009a, 2009b). Moreover, the incidence of pathogens and saprophytes per cultivar is similar, as the three cultivars tested had an incidence percentage with the same group of means.

Table 3 Overall fungal incidence, incidence of pathogens and saprophytes per cultivar in oat seeds obtained from different localities in the central valley of Mexico, during the spring-summer 2009 and 2010 cycles.

*Medias dentro de cada columna seguidas por la misma letra no difieren en la prueba de Tukey al 5% de probabilidad.

In conclusion, the incidence of fungal pathogens in oat seeds from different cultivars, production cycles and localities in the central Valley of Mexico was 15.4%; while the incidence of saprophytic fungi was 48.87%. Moreover, the overall fungal incidence was higher in the Chihuahua cultivar, followed by the Ágata and Turquesa cultivars. In addition, the seeds obtained during the 2009 cycle showed a higher fungal incidence of both pathogens and saprophytes.

Literatura citada

Almeida, M. F. e Reis, E. M. 2009. Comparação da sensibilidade de métodos para a detecção de fungos patogénicos em sementes de aveia branca e preta no Rio Grande do Sul. Tropical Plant Pathol. 34:265-269. [ Links ]

Bautista-Espinoza, M. E.; Leyva-Mir, S. G.; Villaseñor-Mir, H. E.; Huerta-Espino, J. y Mariscal-Amaro, L. A. 2011. Hongos asociados al grano de trigo sembrado en áreas del centro de México. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 29:175-177. [ Links ]

Carmona, M.; Zweegman, J. and Reis, E. M. 2004. Detection and transmission of Drechslera avenae from oat seed. Fitopatol. Bras. 29:319-321. [ Links ]

Clear, R. M.; Patrick, S. K. and Gaba, D. 2000. Prevalence of fungi and fusariotoxins on oat seed from western Canada, 1995-1997. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 22:310-314. [ Links ]

Farias, C. R. J.; Del Ponte, E. M.; Lucca-Filho, O. A. e Plerobom, C. R. 2005. Fungos causadores de Helmintosporiose associados as sementes de aveia-preta (Avena strigosa, Schreb.). Rev. Bras. Agrociéncia. 11:57-61. [ Links ]

Farias, C. R. J.; Lucca-Filho, O. A.; Pierobom, C. R. e Del Ponte, E. M. 2002. Qualidade sanitária de sementes de aveia-preta (Avena strigosa Schreb.) produzidas no estado do Rio Grande do Sul, safra 1999/20001. Rev. Bras. Sementes. 24:1-4. [ Links ]

Jiménez, G. C. 1992. Descripción de las variedades de avena cultivadas en México. SARH, Campo Experimental Valle de México. Chapingo, Estado de México. 89 p. [ Links ]

Kurowski, T. P. and Wysocka, U. 2009. Fungal communities colonizing grain of hulled and naked oat grown under organic farming system. Phytopathologia 54:53-59. [ Links ]

Lángaro, N. C.; Reis, E. M. and Floss, E. L. 2001. Detection of Drechslera avenae in oat seeds. Fitopatol. Bras. 26:745-748. [ Links ]

Leslie, F. J. and Summerell A. B. 2006. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual. Blackwell Publishing. Iowa, USA. 388p. [ Links ]

Leyva-Mir, S. G.; Mariscal-Amaro, L.A.; Villaseñor-Mir, H. E. y Huerta-Espino J. 2011. Diplodia sp., causante de la pudrición de grano de Avena (Avena sativa) en Nanacamilpa, Tlaxcala, México. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 29:81-83. [ Links ]

Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento (MAPA). 2009. Manual de análise sanitária de sementes. Secretaria de Defesa Agropecuária. MAPA/ACS. Brasília, Brasil. 200 p. [ Links ]

Mortensen, K. and Hsiao, A. I. 1987. Fungal infestation of seeds from seven populations of wild oats (Avena fatua) with different dormancy and viability characteristics. Weed Res. 27:297-304. [ Links ]

Neergaard, P. 1977. Seed pathology. 1. MacMillan Press. Surrey, UK. 1:839 p. [ Links ]

Nyvall, R. F. 1999. Field crop diseases. Iowa State University Press.Iowa, USA. 1021 p. [ Links ]

Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS Institute). 2003 User's guide. Version 9.1. Cary, USA. 1052 p. [ Links ]

Silva, R. T. V.; Homechin, M.; Endo, R. M. e Fonseca, I .C. B. 2002. Efeito do tratamento de sementes e da profundidade de semeadura no desenvolvimiento de plantas de aveia-branca (Avena sativa L.) e a microflora da rizosfera e do rizoplano. Rev. Bras. Sementes. 24:237-243. [ Links ]

Simmons, G. E. 2007. Alternaria: an identification manual: fungal biodiversity centre. Utrecht, Netherlands. 775 p. [ Links ]

Tariq, A. H.; Saed, A.; Hussain, A.; Akhtar, L. H.; Muhammad, A. and Siddiqui, S. Z. 2004. Seed-borne mycoflora on oats in the Punjab. Pakistan J. Sci. Indus. Res. 47:46-49. [ Links ]

Villaseñor-Mir, H. E.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Rodríguez-García, M. F.; Santa-Rosa, H. y Martínez-Cruz, E. 2009a. Ágata, nueva variedad de avena para siembra de temporal en México. INIFAP, Campo Experimental Valle de México. Texcoco, Estado de México. 10 p. [ Links ]

Villaseñor-Mir, H. E; Espitia-Rangel, E.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Osorio-Alcalá, L. y López-Hernández, J. 2009b. Turquesa, nueva variedad de avena para producir grano y forraje en México. INIFAP, Campo Experimental Valle de México. Texcoco, México 23 p. [ Links ]

Warham, E. J.; Butler, D. L. y Sutton, C. B. 1998. Ensayos para la semilla de maíz y trigo. Manual de laboratorio. Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo (CIMMYT). Texcoco, Estado de México. 84 p. [ Links ]

Watanabe, T. 2010. Pictorial atlas of soil and seed fungi: morphologies of cultured fungi and key to species. 3th (Ed.). CRS Press. Boca Raton, USA 3970 p. [ Links ]

Zyllinsky F. J. 1984. Guía para la identificación de enfermedades en cereales de grano pequeño. Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo (CIMMYT). Texcoco, Estado de México. 141 p. [ Links ]

Received: March 2014; Accepted: April 2014

texto en

texto en