Introduction

Mexican migration to the United States represents one of the largest flows of migrants in the world (Borjas, 2007; Ortmeyer and Quinn, 2012). Economic hardships derived from a number of macro-level circumstances push Mexican migrants out of their home country (Martin, 2010; Pisani and Yoskowitz, 2002). Simultaneously, pull factors encourage migration to the United States, such as the prospects of reuniting with family members, higher earning potential, and the ability to remit earnings to relatives in Mexico (Mooney, 2004; Orrenius and Nicholson, 2009). Roughly US$21.5 billion were remitted to Mexican households from migrants residing in the United States in 2009 (Coronado and Canas, 2010). Studies conducted in Europe, the South Pacific, and northern Africa have found that the receipt of remittances increases migration intentions, thus promoting chain migration (Dimova and Wolff, 2009; Leeves, 2009; van Dalen, Groenewold, and Fokkema, 2005). In the Western Hemisphere, this relationship remains largely unexplored despite the fact that high Mexico-U.S. migration rates and the flow of remittances between the two countries are among the largest in the world (Borjas, 2007; Ortmeyer and Quinn, 2012). This represents a significant gap in the literature and one this study sought to fill.

To my knowledge, this study was the first to explore the relationship between remittances and Mexico-U.S. migration, among Mexican adolescents living along the border. To better understand factors influencing the migration intentions of the next generation of migrants, a survey was conducted among a sample of adolescents and young adults living in the border city of Tijuana, Mexico, who were pursuing higher levels of education than the average Mexican. Guided by social capital theory and controlling for having a migrant parent, this study looked at whether household receipt of remittances contributes to subsequent future migration by these Mexican teens. In addition, the potential interaction effect on migration intentions of receiving remittances and having a migrant parent living in the United States was assessed.

Background

Worldwide, just over 214 000 000 individuals live in a country different from the one where they were born (UN, 2011). The United States hosts more of these migrants than any other nation; it is home to nearly one-fifth of all global migrants (43 000 000) (UN, 2011), a disproportionate number of whom are from Mexico. Roughly 28 percent of all immigrants living in the United States are Mexican (12 000 000) (Martin, 2010; Zong and Batalova, 2016). Despite the two countries sharing a highly militarized border, the U.S.-Mexico border is among the most often crossed by international migrants in the world (Massey, Durand, and Malone, 2003; Ortmeyer and Quinn, 2012). Almost 9 percent of Mexico’s native-born population resides in the United States (Borjas, 2007).

Push/Pull Factors in Mexican Migration

Mexican migration to the United States is largely wage labor migration resulting from economic conditions that both push and pull migrants across the border (Massey, Durand, and Malone, 2003; Wilson, 1993). Push factors are negative conditions that propel migrants out of the sending country, while pull factors are positive conditions that draw them to the receiving country (Jenkins, 1977). Several earlier studies reported push factors to be stronger precipitators of Mexican migration (Jenkins, 1977; Frisbie, 1975); however, this conclusion has not been reported in the more recent literature. Instead, push and pull factors are considered to work together synergistically to drive and sustain Mexican migration to the United States (Massey, Durand, and Malone, 2003).

Economic hardship is the primary push factor causing Mexican nationals to move north. Jobs are lacking in Mexico, both in quantity and quality: overall, employment is scarce and wages are poor (Martin, 2010; Pisani and Yoskowitz, 2002). Mexico has 112 million inhabitants, but in 2010, had a formal sector labor force of only 45 million (Martin, 2010). Many factors contribute to the lack of job opportunities, including population growth in recent decades and institutional shifts triggered by the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) (Ong, 2010; Martin, 2010). In the two decades following the 1994 enactment of NAFTA, countless Mexican nationals lost their livelihoods and economic niches in their home country, particularly those working in agriculture; soon thereafter, the number of Mexican immigrants in the United States tripled in size, reaching roughly 12 000 000 (Martin, 2010).

Economic incentive is a pull factor drawing many Mexican migrants to the United States. The significant wage differential between the two countries provides a strong incentive to migrate (Martin, 2010; Pisani and Yoskowitz, 2002). In 2013, the gross national income (GNI) per capita in the United States was US$43 730 higher than Mexico’s (World Bank, 2014). Compared to Mexico, employment in the United States is not just better paid, but also more readily available. The United States has a consistent, strong demand for Mexican migrant workers in construction, hospitality, agriculture, and manufacturing (Kochhar, 2005). This represents an economic opportunity relatively close to home that lures many Mexicans to migrate every year. Reuniting with migrant relatives in the United States is another significant pull factor driving Mexican migration and one that promotes chain migration (Mooney, 2004; Wilson, 1993). Additionally, the opportunity to repatriate a portion of earnings to relatives in the home country is motivating factor (Amuedo-Dorantes, Bansak, and Pozo, 2005).

Remittances

Across the globe, over US$460 billion are remitted by individuals annually (World Bank, 2013). According to the new economics of labor migration, individuals in developing countries work as a coherent unit to function in limited economies and, together, make up for labor-market deficiencies (Stark, 1991). Migrant remittances are the return on the investment of sending family members abroad (Sana and Massey, 2005; Stark, 1991). Remitted earnings act as a form of insurance and informal loan system in lieu of a public safety net and formal borrowing system (Lindstrom, 1996; Sana and Massey, 2005).

Worldwide, the United States is the largest sender of remittances (Mishra, 2007), and Mexico receives the largest share of them (Suro et al., 2002). In 2009, Mexican households received over US$21.5 billion in repatriated earnings from the United States (Coronado and Canas, 2010), and remittances are one of the country’s largest sources of foreign exchange (Ortmeyer and Quinn, 2012).

Repatriated migrant earnings have a variety of impacts at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels in Mexico. At the household level, studies suggest remittances are primarily spent on the consumption of routine goods and family maintenance costs (Massey and Basem, 1992). However, some studies have found that they enable migrants and their relatives to invest in homes and other productive economic activities (Mooney, 2004). At the community level, evidence suggests remittances alter local distribution of income, increase consumer spending, and promote social mobility; this produces greater inequity and a swelling sense of deprivation among non-migrant households resulting in increased migration (Reichert, 1981, 1982; Stark, Taylor, and Yitzhaki, 1986, 1988). Remittances also increase the demand for housing and farmland, inflating land and housing prices (Massey and Basem, 1992). In effect, this further perpetuates migration by forcing nationals to migrate in order to compete in the changing economic climate (Massey and Basem, 1992). At the broader economic level, several studies have concluded that remittances are rarely applied toward investment, precluding them from being income-generating or job-producing; thus, they fail to reduce out-migration (Massey and Bassem, 1992; Reichert, 1981). Similarly, Chami, Fullenkamp, and Jahjah (2003) found an inverse relationship between remittances and gross domestic product growth. It is plausible that several of the direct and indirect effects of remittances on households, communities, and the broader Mexican economy serve to perpetuate migration.

Social Capital Theory

Social capital theory helps explain the forces that perpetuate migration (Massey, Durand, and Malone, 2003; Palloni et al., 2001). Social capital is the accumulation of resources resulting from an individual or group’s formal and informal social networks; the defining feature of social capital is that it can be converted into economic and social benefits (Coleman, 1994). The migrant network is a form of social capital gained through interpersonal relationships and membership in social organizations that produces a chain migration effect (Massey, Goldring, and Durand, 1994; Mooney, 2004). Chain migration is a pattern of migration whereby one or more individuals migrate internationally, later sending for or having family members or close friends join them in the new country (Castañeda and Buck, 2011). Through reciprocal ties between migrant and non-migrant family, friends, and community members, the migrant network increases access to information on the migration experience (Massey, Durand, and Malone, 2003; Massey and García-España, 1987). The migrant network also functions to lower the risks and costs associated with migration, while increasing the expected benefit. It provides social, emotional, and financial support throughout the migration process (Massey, Durand, and Malone, 2003; Massey and García-España, 1987).

Massey and García-España (1987) describe four categories of costs the migrant network minimizes, including: a) lowering expenditures on practical aspects of the migrant’s trip (for example, food and lodging); b) mediating information and search costs associated with finding and securing a job; c) mitigating opportunity costs resulting from missed income due to transition time; and, d) diminishing the psychological costs associated with leaving home and traveling to unfamiliar territory. Wilson (1993) adds to this, suggesting the migrant network also decreases migrant costs through introduction to new labor markets and the provision of informal loans via remittances. Accordingly, social capital provided through the migrant network increases the probability that others will migrate, thereby perpetuating migration (Massey, 1990; Palloni et al., 2001).

Remittances can be thought of as another benefit accrued to the individual from the migrant network and, thus, a form of social capital. As such, remittances have the potential to perpetuate chain migration (Massey, Goldring, and Durand, 1994; Mooney, 2004). Several previous studies have tested and supported this proposition.

Prior Research

Three studies have tested the impact of remittances on chain migration in various countries. Van Dalen and his colleagues (2005) assessed them in Turkey, Morocco, and Egypt, and cross-sectional data revealed that individuals who received remittances in the first two countries were significantly more likely to intend to migrate. In Morocco, individuals who lived in households that received remittances were twice as likely to intend to migrate compared to those who did not receive remittances (14 percent vs. 7 percent). In Turkey, 36 percent of remittance-receiving individuals intended to migrate, whereas only 24 percent of those who did not receive remittances had that intention (van Dalen, Groenewold, and Fokkema, 2005). Using longitudinal data, Dimova and Wolff (2009) examined the effect of remittances on chain migration in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Individuals from households that received remittances were 32 percent more likely to plan to migrate than those that non-receiving households. Furthermore, when participants were asked if they intended to migrate that year, those who received remittances were over two times more likely to say yes. Healthy, young, highly-educated participants who received remittances were the most likely to intend to migrate (Dimova and Wolff, 2009). Using cross-sectional data from Fiji and Tonga, Leeves (2009) examined the relationship between the receipt of remittances and intentions to migrate within the following two years. In both countries, receiving remittances was a predictor of migration intentions. Intentions to migrate were strongest among individuals in remittance-receiving households with a family member abroad. This may indicate that having a migrant family member moderates the relationship between remittances and migration intentions (Leeves, 2009).

This Study

The northward flow of Mexican migrants and the southbound flow of remitted U. S. earnings are substantial and among the highest migrant exchanges in the world. Nonetheless, to my knowledge, the impact of remittances on Mexican chain migration to the United States has yet to be examined. Building on social capital theory, the purpose of the present study was to examine the relationship between the receipt of remittances, a form of capital and derivative of one’s migrant network, and migration intentions among a sample of highly educated Mexican adolescents living along the Mexico-U.S. border.

Researchers studying Mexican migration to the United States often sample individuals who have lower educational levels, earn lower wages, and are undocumented (Hanson, 2007; Kanaiaupuni, 2000). Studies also tend to be conducted with Mexican migrants from central and southern Mexico, the region the majority of migrants are from (Massey Durand, and Malone, 2003). However, this study sampled a unique sub-population of prospective migrants from Tijuana, the second largest Mexican city bordering the United States. Adolescents and young adult Mexican nationals who were pursuing higher levels of education than the average student and who tend to have a higher liklihood of migrating legally to the country were surveyed. In general, borderland migrants have different access to the United States, opportunity structures, and demographic profiles (Becerra et al., 2010). The likelihood of legal migration from Tijuana to the United States is greater than from other regions in Mexico since family and business networks in Southern California facilitate migration; thus, Tijuana sends the highest proportion of documented migrants to the United States. Migrants from this metropolitan border area also tend to be younger than those from other regions of Mexico (Fussel, 2004).

This study was guided by the hypothesis that highly educated adolescents living along the Mexico-U.S. border who lived in remittance-receiving households would have higher migration intentions than those from households not receiving remittances. This proposition derives from social capital theory, in which benefits from one’s migrant network, including economic benefits via the receipt of remittances, facilitate the migration process and thus positively influence the intention to migrate. Additionally, it is supported by the literature on push-pull factors in Mexican migration that shows economic incentive as a significant driver of migration; remittances may have a signaling effect that reinforces the perceived economic benefits of migration. The literature on the impact of remittances also supports this hypothesis; they tend to be used for family maintenance costs but are often not used for investments, preventing them from generating further income and reducing subsequent migration (Massey and Bassem, 1992; Reichert, 1981). Finally, anticipation of a positive relationship between remittance receipt and migration intentions among a young and more highly educated sample of Mexicans is consistent with Dimova and Wolff’s (2009) finding that the remittance-receiving Bosnians and Herzegovinians most likely to intend to migrate were the young and highly educated.

To help discern if intentions to migrate were driven by the effect of remittances or the relationship with migrant senders, and account for possible endogeneity of the two, this study both controlled for the presence of migrant parents and examined whether an interaction effect between remittance receipt and the presence of a migrant parent on migration intentions was supported. The hypothesis was that having a migrant parent would interact with the receipt of remittances, such that those who had a parent abroad and received remittances would have the strongest migration intentions.

Methodology

A cross-sectional survey design was used in this study to examine the impact of remittances on the migration intentions of highly educated borderlands adolescents. Following review and approval from the institutional review board and securing parental consent, data were gathered at one preparatoria -roughly equivalent to a United States high school- within three miles of the U.S.-Mexico border in Tijuana. The preparatoria offers studies in the following areas: administration, nutrition, environmental conservation, and computer science. Upon completion of preparatoria, students receive a technical degree and license to work in those areas. Data were collected in February 2009, and approximately 75 percent of the preparatoria’s total student population completed and returned the study’s questionnaires. Questionnaires were distributed in the students’ classrooms and participants completed them in Spanish.

Sample

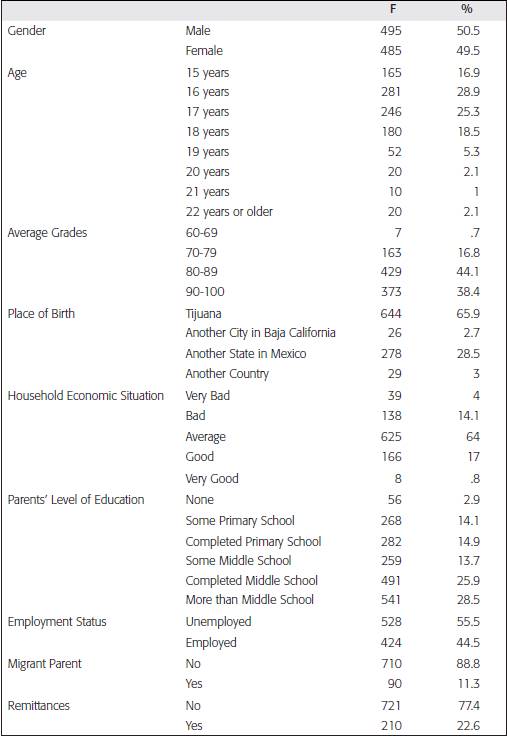

A non-probabilistic sample of adolescents from the preparatoria was surveyed for the present study (N = 980). Table 1 contains the demographic information of the study participants. There were 485 female participants and 495 male participants. The participants self-reported their ages, and the mean was 16. Over 82 percent of participants reported their average school grades as between 80 and 100 (equivalent to a B to A average). Almost two-thirds were born in Tijuana, and over 62 percent indicated their families had a very low to average socioeconomic status, as measured by a socioeconomic status (SES) scale. The majority of participants’ mothers (74.2 percent) and fathers (68.6 percent) had less than a high school education.

Measures

The remittances variable was a single item, which asked “Does a family member living in the United States send money to your family?” (0 = no, 1 = yes). Having a migrant parent was used as a control; participants were asked whether one or both parents lived in the United States and response options were coded 0 = no and 1 = yes, if at least one parent lived in the country. Table 2 illustrates a crosstab of the remittances and migrant parents variables. Gender was coded 0 = male and 1 = female. Average grade scores in school were coded 1 = less than 60, 2 = 60-69, 3 = 70-79, 4 = 80-89, 5 = 90-100. The educational levels of participants’ mothers and fathers were coded from 0 = no schooling to 5 = bachelor’s degree or higher. Work status was determined through a single question, which asked participants, “In the past month, did you work for pay?” The response options were coded 0 = no and 1 = yes.

For the dependent variables, participants were asked three Likert questions/ statements (1= strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree) regarding their intentions to migrate to the United States: 1) “Would you like to live in the U.S. someday?”; 2) “Would you like to work in the United States someday?”; and 3) “When I graduate from high school I am going to migrate to the United States.” Intentions to migrate were used as a proxy for probability to migrate, a common practice in the migration literature; multiple studies have verified intentions to be an acceptable predictor of actual migration (Dimova and Wolff, 2009; Dustmann, 2003).

Analysis

Three hierarchical regression analyses with each dependent variable were completed to determine the relationship between the receipt of remittances and intentions to migrate to the United States. Each regression analysis was completed using four blocks. The first block consisted of the control variables: gender, age, average grades in school, parents’ educational level, and work status. Because having close family members in the U.S. increases the likelihood of subsequent migration, the second block added “migrant parent,” and the third block added the variable of interest, “remittances.” A moderation analysis was conducted in the fourth block to see if having a parent living in the United States moderated the impact of receiving remittances on participants’ migration intentions. Following the standards of Cohen and Cohen (1983), a moderation effect would be considered to exist if the interaction term had a statistically significant coefficient and resulted in a statistically significant increase in the amount of variance explained in migration intentions.

Results

As illustrated in Table 3, the first regression analysis examined the impact of remittances on wanting to live in the United States someday and was performed in four steps. The first model contained the control variables and was significant: F (5, 704) = 2.50, p = .029, accounting for the 1.7 percent of the variance in migration intentions (R2 = .017). The second model added “migrant parents” and was not significant: F (6, 703) = 2.08, p = .053. The third model, which added “remittances,” was significant: F (7, 702) = 2.48, p = .016 and accounted for the 2.4 percent of the variance in intentions to migrate (R2 = .024). Among the control variables, a significant negative relationship existed between the father’s level of education and participants indicating they would like to live in the U.S. someday (B = -.092; SE = .028; p = .001). A significant positive relationship existed between the receipt of remittances and wanting to live in the United States someday (B = .216; SE = .099; p = .029). The fourth and final model with the interaction term, remittances migrant parent, was significant: F (8, 701) = 2.19, p = .026; however, the interaction term was not significant.

Table 3: Hierarchical regression: Relationship bewteen remittances and "someday I would like to live in the U.S."

Notes: Total R2 =.024; adjusted R2 =.013. F (8, 701) = 2.19, p = .026.

* p <.05,

** p <.01,

*** p <.001.

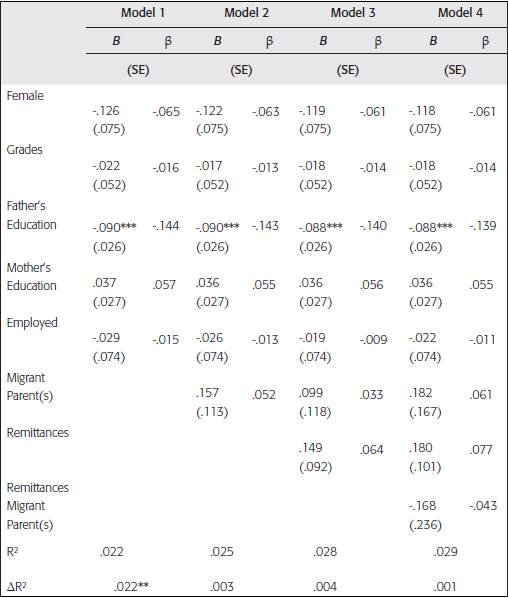

Table 4 demonstrates the results of the second four-step regression with “desire to work in the United States someday” as the dependent variable. The first model with the control variables was significant: F (5, 703) = 3.13, p = .008 and accounted for the 2.2 percent of the variance in migration intentions (R2 = .022). The second model, which included “migrant parents,” was significant: F (6, 702) = 2.94, p = .008, accounting for 2.5 percent of the variance in migration intentions (R2 = .025). The third model with “remittances” added was also significant: F (7, 701) = 2.90, p = .005 and accounted for 2.8 percent of the variance in intentions to migrate (R2 = .028). Among the control variables, a significant inverse relationship existed between the father’s educational level and participants indicating they would like to work in the United States someday (B = -.088; SE = .026; p = .001). No significant relationship existed between the receipt of remittances and wanting to work in the U.S. someday. The fourth and final model with the remittances migrant parent interaction term was significant: F (8, 700) = 2.60, p = .008; however, the interaction term was not significant.

Table 4: Hierarchical regression: Relationship bewteen remittances and "someday I would like to work in the U.S."

Notes: Total R2 =.022; adjusted R2 =.015. F (8, 700) = 2.60, p = .008.

* p <.05,

** p <.01,

*** p <.001.

Table 5 contains the results of the third four-step regression analysis with the dependent variable “I am going to move to the U.S. when I graduate.” The first model contained the control variables and was significant; F (5, 695) = 5.84, p < .001, accounting for 4 percent of the variance in migration intentions (R2 = .040). The second model, which added “migrant parents,” was significant: F (6, 694) = 6.70, p < .001 and accounted for 5.5 percent of the variance in migration intentions (R2 = .055). The third model added “remittances” and was significant: F (7, 693) = 6.78, p < .001, accounting for 6.4 percent of the variance in intentions to migrate (R2 = .064). Among the control variables, a significant inverse relationship was found between being female (B = -.217; SE = .077; p = .007) and having higher grades (B = -.133; SE = .053; p = .012) and migration intentions. A significant positive relationship existed between the mother’s educational level (B = .064; SE = .028; p = .022) and having a migrant parent (B = .285; SE = .122; p = .019), impacting participants’ plans to move to the United States. A significant positive relationship also existed between the receipt of remittances and planning to move to the U.S. after graduation (B = .245; SE = .093; p = .009). The fourth model included the moderation analysis with the interaction term remittances migrant parent and was significant: F (8, 692) = 5.92, p < .001; however, the interaction term was not significant.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of remittances on the migration intentions of adolescents and young adults pursuing higher-than-average levels of education and living along the Mexico-U.S. border. With the exception of wanting to work in the United States, findings supported the hypothesis that adolescents from remittance-receiving households have greater migration intentions than those from households that do not receive remittances. The receipt of remittances was a statistically significant predictor of wanting to live in the United States someday and planning to move there after graduation. As social capital theory would indicate, remittances may represent an important economic resource from individuals’ migrant network that provide the initial capital needed to consider migration. Alternatively, as the literature on push and pull factors supports, remittances may increase migration intentions through a signaling effect that underlines the economic gain associated with international migration. These findings are consistent with previous studies in other regions of the world that have found remittances to be related to increased migration intentions (Leeves, 2009; van Dalen, Groenwold, and Fokkema, 2005), including Dimova and Wolff’s 2009 report of this relationship being especially strong among the young and highly educated.

Receiving remittances may not have been related to wanting to work in the United States someday, as participants may be focused on post-secondary education and not yet considering employment. Alternatively, participants may view their employment prospects in Mexico as sufficient to meet their needs and goals. Although the average level of education in Mexico has increased in the past 20 years so that the average number of completed school years among 15-24-year-olds in Mexico is now 10 school years (INEE, 2013), 76 percent of adults ages 25-64 in Mexico have not completed preparatoria (OECD, 2015). Therefore, by studying at a preparatoria, the sample population for this study has a relatively higher educational level than the majority of Mexico’s population. Compared to the U.S., there is a higher return on investment in education with a higher percentage wage increase for each additional year of schooling in Mexico; this may impact the migration intentions of more highly educated adolescents in Mexico.

Because having family members in the U.S. is a pull factor for subsequent migration (Mooney, 2004), this study controlled for migrant parents and examined if having a migrant parent moderated the relationship between remittances and migration intentions. Findings did not support the hypothesis that those that have a parent abroad and receive remittances have the highest migration intentions. Although the main effect of having a migrant parent increased intentions to migrate to the U.S. after graduation, the interaction term remittances migrant parent was not significant. This indicates that, among this sample population, the receipt of remittances incited migration intentions independently of the influence of migrant parents. This diverges from findings in the South Pacific, where intentions to migrate were strongest among individuals who received remittances and had migrant family members (Leeves, 2009).

Future Research

The nascent understanding of the relationship between remittances and Mexico-U.S. chain migration calls for further research. To the best of my knowledge, this study was the first to explore the impact of remittances on Mexican migration intentions among adolescents and young adults pursuing higher levels of education than average and living along the U.S.-Mexico border. The sample used in this study was not a random probability sample, which is a limitation. While the results are suggestive of a relationship between remittances and migration intentions among higher-thanaverage educated Mexican adolescents and young adults living in a border city, findings cannot be generalized to the entire adolescent or young population in Tijuana or other regions of Mexico. Adolescents and young adults in different schools or who are no longer in school may have different migration intentions, as well as different factors affecting those intentions. Therefore, future research is needed to explore the relationship between remittances and the migration intentions of other Mexican adolescents. A multi-site study design would be helpful in lending greater clarity to the relationship between remittances and migration intentions for a more diverse group of individuals. In addition, ideally, a study that randomly samples all Mexicans would be conducted. This would allow findings to be referred back to the general Mexican population and determine if the receipt of remittances is a pull factor for Mexican migration in general.

Beyond replication of results among more representative and diverse samples, further research should expand upon the finding that receiving remittances increases migration intentions. First, it should explore the possibility of a progressive relationship between remittances and migration intentions as the quantity of remittances increases. Second, a longitudinal study of remittance recipients should be conducted to determine if remittances translate into actual migration beyond increased migration intentions. Alternatively, a retrospective study of Mexican migrants living in the U.S. could be done. While quantitative research should continue to empirically validate the relationship between remittances and migration intentions, qualitative research should also be done to help elucidate the exact nature of that relationship. It is not currently understood why or how remittances increase migration intentions. For example, remittances may have a signaling effect leading more highly educated Mexican adolescents to consider migration. Alternatively, remittances may provide the capital needed to consider migration.

Immigration Policy

While more highly educated adolescents from Tijuana have a greater chance of migrating to the U.S. legally, much of the flow of migrants from Mexico is undocumented labor migration. It is driven by a significant wage-rate differential between the U.S. and Mexico. While this differential cannot feasibly be targeted to curb undocumented migration, the pathways for legally migrating to the U.S. can be targeted. Current opponents to immigration reform in the U.S. are primarily concerned with the economic costs to U.S. taxpayers without considering its potential economic benefits for the U.S. economy (Becerra et al., 2012). More highly educated and skilled workers in particular would benefit multiple sectors of the U.S. economy. In order to address issues related to Mexico-U.S. migration, U.S. immigration policies warrant reform to better reflect the economic realities of the two countries and the demand for skilled and unskilled labor in the U.S. The integration of migration policy with economic development and poverty-reduction policies in Mexico and the U.S. would be more effective than existing policies (Adams and Page, 2005). Current U.S. restrictive immigration policies make circular migration extremely difficult, dangerous, and costly and may prevent the positive economic impact of migration and remittances from being fully realized for both the U.S. and Mexico. As De Haas (2005) argued, it is useless to try to completely stop migration as it is inevitable; therefore, creating policies that facilitate circular migration and remittances may actually help control migration and offer greater economic benefits to both countries.

The results of this study suggest that migration to the U.S. remains a goal for adolescents, even those with higher educational levels, skills, and training. Currently, only 20 000 permanent immigrant visas are granted to Mexicans annually. This is the same number allotted to the Dominican Republic despite Mexico having a population over 10 times that of the small Caribbean nation, and sharing a 2 000 mile border and complicated migration history with the U.S. (Rosenblum et al., 2012; Schmitter, 2008). The expansion of legal migration pathways would replace the need for clandestine border crossings. The saturation of the labor market with authorized migrant workers would also probably reduce undocumented migration by decreasing the demand for undocumented workers, as it would reduce the financial incentive for undocumented migration. Immigration reform that includes the expansion of H-1B, L-1, and EB visas would impact not only migration patterns, but also probably the effect of remittances on the migration intentions among Mexican adolescents as well.

Conclusion

The U.S.-Mexico border has one of the highest numbers of migrant border crossings in the world. Accordingly, repatriated earnings from migrants working in the U.S. represent a significant proportion of the total share of global remittances. Despite this, the impact of remittances on the next generation of prospective migrants to the U.S. is an underexplored area of study. Drawing from social capital theory, this study examined the impact of remittances on Mexican chain migration among adolescents and young adults pursuing higher-than-average levels of education and living along the border. Findings were consistent with previous studies and indicated that the receipt of remittances greatly increased migration intentions. This study also explored the possible moderating impact of having migrant parents; however, no indication was found that remittances have an impact on migration intentions independent of having migrant parents in the U.S. The findings serve as a guide for future migration research and warrant policy changes geared toward the expansion of legally authorized migration pathways to the U.S.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)