| Table of Contents | ||

|---|---|---|

| I. | Introduction | 100 |

| II. | Re-focusing communist survival in cuba | 102 |

| 1. | Defining the problem | 102 |

| 2. | An alternative analytical approach | 104 |

| III. | Addressing change | 106 |

| 1. | Leadership: from charisma to collegiality | 107 |

| 2. | Ideology: from cpe to market socialism | 112 |

| IV. | Explaining change | 116 |

| 1. | Regime-type development | 117 |

| 2. | Cuba in (brief) comparative perspective | 121 |

| V. | Conclusions | 123 |

I. Introduction

It has been a decade since Raúl Castro succeeded his brother Fidel as President of Cuba and First Secretary of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC, by its acronym in Spanish). On the 31st of July 2006, after falling ill, Fidel Castro wrote a Proclamation that “provisionally” delegated power to Raúl.1 In 2008, however, Raúl’s takeover became definitive. Soon after, he launched a reform process that reverberates until today. Two Party Congresses have been held since then (in 2011 and 2016), where the main goal has been to ‘update’ the Cuban ‘economic and social model’. That the post-Fidel transition has tested the Cuban political system is an understatement.

However, most international attention on Cuba has recently focused in the normalisation of its relations with the United States -a diplomatic breakthrough that Raúl Castro and Barack Obama announced in December 2014 in simultaneous speeches in Havana and Washington, respectively. Although this development says more about the United States changing its approach towards Cuba rather than the other way around,2 this does not mean that Cuba has not changed at all under Raúl Castro. Quite the contrary, Washington has noted that Cuba has changed, which is why it has modified its diplomatic stance in the first place -now it pursues its interests by trying to engage the expanding Cuban private sector.3 The fact that the new US-Cuba relations have only emerged eight years after Fidel Castro stepped down and Raúl Castro took over, must serve as a reminder that the internal factors shaping Cuba deserve equal if not more attention than the external ones in order to understand how and why the Cuban polity has changed. Such a premise has laid the foundation of this article.

Drawing on the literature of post-totalitarian rule, I argue that between 2006 and 2016 Cuba experienced a change from a charismatic post-totalitarian regime to a maturing post-totalitarian one. The basic argument behind these concepts (that I will later explain) is that the loss of Fidel Castro’s charismatic authority -he stepped down in 2006- pushed forward economic performance as a compensatory source of legitimacy, which helps to explain the market reforms adopted by Raúl Castro.

This characterisation is opposed to one proposed by Steven Saxonberg, who draws on the same literature.4 This author has provided a sophisticated framework to understand the survival of communist rule in Cuba, China, North Korea and Vietnam. His comparative study on a multi-region range of cases (fourteen, as he also discussed many non-survival cases) is an important contribution to the analysis of communist political systems. This said, I contend that Saxonberg has poorly applied his own model to understand the survival of Cuba, which he equates to North Korea on the ground that in both cases the Soviet-style economy prevails and power has been transferred within the same family -from father to son, in Pyongyang; and from brother to brother, in Havana. I refute this take on the Cuban regime -valid for Saxonberg as far as 2013- not least because Raúl has introduced market reforms that have revised the previous economic ideology and because beyond Raúl and Fidel there is no other Castro family member in the line of succession.

In this article I thus re-apply Saxonberg’s own theory to the analysis of contemporary Cuba. In doing so, nevertheless, I challenge some assumptions in regards to both his evolutionary theory of communist rule and his conceptualisation of the Cuban case.

The Sixth Congress of the PCC held in April 2011 marked the culmination of Raúl Castro’s consolidation of power. By then, 1) the leadership had already lost the charismatic character granted by Fidel Castro’s decades-long tenure; and, 2) the ruling ideology had started a departure from the centrally planned economy (CPE). The key argument of this article is that both changes are related as the loss of charisma helped to increase the weight of economic performance, thus re-shaping the regime’s claims to legitimacy.

As Raúl Castro has confirmed that he will step down in 2018 -when his second five-year presidential tenure comes to an end, the contours of the new regime analysed here are arguably those of what will be the initial conditions of the post-Castro era.

In the next section, I provide the theoretical framework of this study. I will define Cuba as Raúl Castro ‘received’ it -i.e. a charismatic post-totalitarian regime- and I will theorise why the decline of charisma can boost a performance-based legitimacy. In the third section, I discuss how the Cuban regime has changed. I argue that the charismatic leadership turned into a collective arrangement and that the ideology swerved from CPE orthodoxy to a market socialist approach. In the fourth section, I explain why these changes are related in the re-equilibration of the regime’s legitimacy, which I will situate in (abridged) comparative perspective. Cuba is a new maturing post-totalitarian regime, thus joining contemporary China and Vietnam within the same regime-type… without the restoration of capitalism (for now).

II. Re-focusing communist survival in Cuba

1. Defining the problem

In their seminal work, Linz and Stepan argued that 20th-century regimes could be divided into five ideal types: democracy, authoritarianism, totalitarianism, post-totalitarianism, and sultanism.5 Crucially, the post-totalitarian regime differs from the other four in that “it is not a genetic type but an evolutionary type”.6 Based on this notion, they developed a framework to analyse the transitions from communist rule, which Saxonberg has taken to a new, more sophisticated level. Instead of adding a new study on the fall of communist rule, Saxonberg has focused on communist survival in contemporary Cuba, China, North Korea and Vietnam. Thus, he took the post-totalitarian approach out of its original focus on European Communism and advanced a general argument -regardless of region.

Also, Saxonberg has advanced a theory of why post-totalitarian rule emerges in the first place. In his account, totalitarian rule is a temporary “messianic phase” -marked by revolutionary fervour- after which “the regime begins to institutionalise itself ”.7 The early post-totalitarian stage is the outcome of such a relaxation process. His basic argument is that a salient element of the early stage is the endurance of socialist ideology as a key claim to legitimacy -an ideological legitimacy that is eventually undermined by the CPE failures. Once this de-legitimisation process reaches a certain critical point, the regime enters the “late post-totalitarian” stage marked by a shift toward performance-based legitimacy:

The communist regimes lose their grand-future oriented beliefs and instead promise improves living standards. Consequently they try to reach some sort of social contract with the population in order to induce it to “pragmatically accept” that given certain external and internal constraints, the regime is performing reasonably well.8

As this shift is likely to produce a crisis, the regime either moves into a “freezing” direction (the reformist path is stopped or reversed) or a “maturing” one (the reformist path continues). Applying this model, Saxonberg proposes that China and Vietnam had long been on a maturing post-totalitarian path. While in the European cases the ideological legitimacy was lost because of the erroneous belief that the CPE model was superior to advanced capitalism, China and Vietnam have lost their (socialist) ideological legitimacy because they have, ironically, restored capitalism.9 Hence, these regimes would have remained in power because they bypassed their ideological predicament by building their pragmatic acceptance on capitalist ground.

In regards to Cuba and North Korea, Saxonberg argues that both cases have long become patrimonial (Fidel Castro became a dynastic ruler like Kim Il Sung), the difference being that Cuba overlaps with freezing post-totalitarian rule, while North Korea does so with totalitarianism (hence, both cases stick to CPE).10 Under this view, these regimes turned to patrimonial rule in order to avoid collapse.

However, Saxonberg has ignored a previous post-totalitarian analysis of the Cuban case. Although Linz and Stepan had limited their typology to the comparative analysis of European Communism, Mujal-León and Busby later applied their toolkit to characterise the Cuban regime after 1990, which they termed a “charismatic early post-totalitarianism” -incidentally, a solution Linz later agreed with.11 As Linz and Stepan defined the typical totalitarian leadership as “often charismatic”, the peculiarity of Cuba, according to Mujal-León and Busby, was not so much the presence of charisma, but its persistence beyond the phase in which such element was supposed to be endemic.12 The counter-intuitive argument was that the importance of Fidel Castro’s charisma to the Cuban regime had “increased by the scope of the crisis in the 1990s” -i.e. “the crisis spawned by the collapse of the Soviet Union […] made him even more indispensable”.13

In contrast, Saxonberg holds that Cuba became a patrimonial communism -i.e. a concept applied by Linz and Stepan to Romania, which López later extended to Cuba,and that Saxonberg picked up and applied to North Korea as well.14 However, Mujal-León and Busby had already objected to the sultanistic (or ‘patrimonial’) label for the 1990s Cuban regime “not least because of its reliance on ideology and mobilisation.”15 According to Saxonberg, Cuba lost its ideological legitimacy since the early 1990s, and had been on a freezing post-totalitarian path since the late 1980s. As I will argue, socialist ideology is still a key claim to legitimacy in today’s Cuba and the economic reform launched by Raúl Castro is a clear case of maturation.

2. An alternative analytical approach

Now, what happens to a charismatic early post-totalitarian regime if its charisma fades? My proposition is that the finale of charisma can change the style (and power) of the leadership, which in turn can modify the regime’s legitimation strategy.

Different Communist systems built its leadership on charismatic legitimacy, to use Weber’s classic term16 -i.e. on the devotion to Stalin (Russia), Mao (China), Tito (Yugoslavia), Enver Hoxha (Albania), Kim Il-Sung (North Korea), or Fidel Castro in Cuba. However, most post-totalitarian transitions were accompanied (or sometimes sparked) by the dissipation of charismatic authority. According to Linz and Stepan, the post-totalitarian regime institutionalises “checks on top leadership.”17 I define this change as a turn to collective leadership or collegiality, which refers to “specific social relationships and groups which have the function of limiting authority”, to use Weber’s words.18 Weber also stressed, to avoid confusion, that “collegiality is no sense specifically democratic”, though it is an arrangement “to prevent the rise of monocratic power.”19

But what happens if collegiality replaces charisma when the regime (apart from its leadership) has already entered the early post-totalitarian stage? First and foremost, this means that two anachronistic legitimation strategies had co-existed:

Charismatic: as analysed by Mujal-León and Busby in regards to the renewed role of Fidel Castro’s leadership in Cuba after 1990

Ideological: as theorised by Saxonberg as a highly distinctive feature of post-totalitarian regimes in their early stage

If the former dissipates, the strategic importance of the latter will increase. At that point, the regime may be said to have experienced a post-totalitarian normalisation -i.e. hybridity ends because the leadership is no longer totalitarian (charismatic), which moves the regime closer to the ideal early post-totalitarian stage. The causal chain may be theorised as follows: if a charismatic early post-totalitarian rule loses its charismatic leadership, its reliance on ideology as a central piece of its claims to legitimacy will confront the regime sooner rather than later with Saxonberg’s dilemma, namely that the regime will have “to choose between either losing their ideological legitimacy by sticking to their ideology and having it fail, or giving up their ideology in order to meet their economic goals”.20 As explained above, the first alternative is the freezing path, and the second, the maturing one.

In other words, Saxonberg identifies two solutions to the dilemma:

- Sticking to the centrally planned economy (CPE)

- Introducing market reforms (in the sense of capitalist restoration)

However, I propose a third, intermediate theoretical solution that destabilises the dilemma posed by Saxonberg and its presupposition that non-capitalist economic formations are incompatible with market mechanisms. The third solution would then be as follows: instead of having to choose between Soviet-style orthodoxy and capitalist restoration, ideology itself may be modified in a manner that redefines the boundaries of admissible economic action according to socialist ideas. In the language of constructivist or discursive institutionalism, the alternative advanced here implies that ideas can change and even shape political processes -as opposed to the fixed nature of communist ideology in Saxonberg’s model.21

In other words, the rise of performance-based legitimacy in communist polities does not inevitably lead to capitalism. A viable path is thus the emergence of ‘market socialism’, which has been defined as “an attempt to reconcile the advantages of the market as a system of exchange with social ownership of the means of production”.22 Curiously, although Saxonberg has classified the Yugoslavia of the 1970s as a maturing post-totalitarian regime, he has ruled out any market-socialist potential for any other case.23 Nonetheless, this article argues that, within the decade following Raúl’s rise to power in 2006, Cuba adopted a maturing, market socialist path. It is still premature, however, to predict the fate of this path as it can get stuck or ‘frozen’ in Saxon-berg’s terms. This said, the regime’s bid is clear: bringing the market without the formation of a capitalist class -a clear-cut market socialist approach.

In summary, if charismatic early post-totalitarian rule ‘runs out’ of charisma (ergo, also the legitimacy granted by it), the regime will rapidly enter the late stage -i.e. Saxonberg’s dilemma. If the regime responds to the new situation by adopting a performance-based legitimation strategy (still) constrained by socialist ideology, a likely outcome is a market-socialist style of post-totalitarian maturation.

III. Addressing change

In this section, I argue that the Cuban regime during the presidency of Raúl Castro has experienced a ‘double political shift’ at the levels of leadership and ideology. On the one hand, I claim that the charismatic nature of the leadership has been replaced by a collegial arrangement -i.e. Raúl Castro did not become a patrimonial ruler. On the other hand, I hold that the orthodoxy of CPE ideology has softened in favour of market-socialist solutions -i.e. the regime is far from ‘freezing’. After discussing the changes in leadership and ideology, in the next section I will address the relationship between them as part of the transformation of the Cuban regime.

1. Leadership: from charisma to collegiality

When Fidel fell ill in July 2006, he provisionally delegated his posts of president of the Council of State and first secretary of the PCC to his younger brother Raúl -long-time head of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR, in Spanish) and second secretary of the PCC. This change would bring a new era in the leadership of the Revolution.

Kapcia has cleverly described the Cuban leadership as an “onion”, “with real power at the centre (an ‘inner circle’), outside which were layers of lesser influence, weakening the further from the ‘core’ now went”.24 The nucleus was, of course, the veteran mountain guerrilla, known in Cuba as the historical generation (generación histórica) who fought in the Rebel Army that won the 1959 revolution.

For Mujal-León the inner circle resembled a charismatic community for its “dependence and unswerving loyalty toward the comandante en jefe” -i.e. the Commander-in-Chief, Fidel Castro, who was the unrivalled leader of the historical generation from 1959 to 2006, and thus, of the elite ruling Cuba.25

Of course, this does not mean that charisma acted in an institutional vacuum or that it was the sole political force. Fidel’s charismatic authority, as Mujal-León and Busby have explained, “also had an institutional aspect of which the PCC and the FAR have not been the only, but certainly the most important tools”.26 In other words, the FAR and the PCC became the “two main pillars” of the Cuban state - of which Fidel Castro remained “the key figure”, as Klepak has put it.27 As charisma “in its pure form” only exists in statu nascendi and thus it eventually undergoes a routinisation process -i.e. it must be either “traditionalised” or “legalised” according to Weber, the FAR-PCC coalition may be seen as the legal-rational routinisation of Fidel’s charismatic authority.28

Although during his provisional rule (2006-2008) Raúl did not reshape the leadership, he did advance a more consultative decision-making style since his first days in power.29 Later, after being appointed president in February 2008, he overhauled the top leadership. Between 2008 and 2009 Raúl dismantled the Support Team of the Commander-in-Chief -also simply known as the “Grupo de Apoyo- which acted as a “parallel structure of government that answers to only [Fidel] Castro and is an extension of his power”.30 As part of this move, Raúl Castro did not hesitate to fire the top leaders that owed their careers to their service in the Grupo de Apoyo, such as vice-president Carlos Lage and Foreign Minister Felipe Pérez Roque, whom had developed charismatic claims to succession.31

After re-shaping, between 2008 and 2009, the leadership he inherited from Fidel, Raúl would unveil his own approach to the succession question in April 2011, when he told the delegates of the Sixth Party Congress that it was “advisable to recommend limiting the time of service in high political and State positions to a maximum of two five-year terms”.32 Less than a year later, in order “to prepare the gradual renovation of cadre”, term limits became the official Party line.33 As Weber explained, the “principle of collegiality […] is usually derived from the interest in weakening the power of persons in authority.”34 In this sense, term limits can be understood as a form of collegial relation for the introduction of term limits attests to the intention of turning to a more collective style of decision-making -as opposed to the undefined duration of charismatic rule.35

Advanced since 2011 by Raúl himself as a means of succession for him and his generation of leaders, the new collegial arrangement is far from Saxonberg’s review of the Cuban case, according to which “a successful [patrimonial] succession took place within the ruling dynasty, as Fidel Castro’s brother, Raúl, replaced him when he stepped down for health reasons.”36 But a different picture emerges at a closer look. Crucially, although the brotherly bond between Fidel and Raúl was indeed “a vital resource […] in resolving the issue of succession”, it was not a case of “a transfer of charisma by heredity”, as Hoffmann has explained.37 Addressing the issue of succession, Raúl discarded any transfer of Fidel’s charisma to the future as early as July 2006:

The special trust granted by the people to the founding leader of the Revolution cannot be transmitted, as if it was an inheritance, to those who hold the main leadership posts of the country in the future. The Commander-in-Chief of the Cuban Revolution is one and only one, and only the Communist Party […] can be the worthy heir of the trust deposited by the people in its leader.38

This solution defined Cuba’s succession problem, not in terms of who would succeed this or any other leader, but which institutional order would constrain any future leadership (principle of collegiality). Far from trying to establish a Castro dynasty akin to the Kim’s in North Korea, Raúl said goodbye to charismatic rule, advancing “a much more institutions-based model” instead; in other words, “Raúl Castro’s thesis that the answer to succession is institutionalization has carried the day”.39

To catch a glimpse of the conditions in which collegiality is expected to operate after the historic generation is gone, it is worth it looking at the core team since Raúl took over -those Politburo members with a seat on the Council of State. If one looks at Table 1 and visualises the ‘core team’ without the revolutionary veterans, what is left is a FAR-PCC collegial partnership that will be led by someone different every five or ten years.

Table 1 Members of PCC Politburo with Joint Appointments to the Council of State

| Status in the Council of State | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politburo member | 2008a | 2011b | 2016c | Background | Entrance/Exit Politburo |

| Raúl Castro Ruz | President | President | President | REV | |

| José Ramón Machado Ventura | 1st VP | 1st VP | VP | REV | |

| Ramiro Valdés Menéndez | VP (Dec 2009) | VP | REV | ||

| Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez | 1st VP (Feb 2013) | PCC | |||

| Leopoldo Cintra Frías | Member | Member | Member | FAR | |

| Salvador Mesa Valdés | Member | VP (Feb 2013) | PCC | ||

| Alvaro López Miera | Member | Member | FAR | ||

| Juan Almeida Bosque | VP | REV | Died in 2009 | ||

| Julio Casas Regueiro | VP | VP | REV | Died after 2011 election | |

| José Ramón Balaguer Cabrera | Member | PCC | Not reelected in 2011 | ||

| Esteban Lazo Hernández | VP | VP | PCC | Not reelected in 2016 | |

| Carlos Lage Dávila | VP | GA-PCC | Removed in 2009 | ||

| Abelardo Colomé Ibarra | VP | VP | FAR | Resigned in 2015 | |

| Lázara Mercedes López Acea | VP (Feb 2013) | PCC | Added in 2011 | ||

| Jorge Marino Murillo | Member | Member | FAR-TECH | Added in 2011 | |

| Bruno Eduardo Rodríguez Parrilla | Member | PCCTECH | Added in 2012 | ||

| Ulises Guilarte de Nacimiento | Member | PCC | Added in 2016 | ||

| Miriam Nicado García | Member | TECH | Added in 2016 | ||

| Teresa Amarelle Boué | Member | PCC | Added in 2016 | ||

Key: VP = Vice President; REV = Revolutionary Generation; FAR = Military; PCC = Cuban Communist Party; GA= Support Group of the Commander-in-Chief; TECH = Technocrat.

Sources: Granma and Juventud Rebelde; data for 2011 taken from Mujal-León.40

a Membership at the moment Raúl Castro took over as President in February 2008.

b Membership as of September 2011.

c Membership as of August 2016.

After 2011, the core team experienced some changes that underpinned the collegiality of the Cuban leadership. In February 2013, during the National Assembly that confirmed his second and last presidential term, Raúl Castro ratified: “this will be my last term”.41 In that same event, the promotion of Miguel Díaz-Canel to First Vice President of the Council of State signalled the first time ever that a revolutionary veteran did not hold that position.42 The end of Raúl Castro’s presidency in 2018, ceteris paribus, will then bring to the fore the FAR-PCC coalition: the true successor (not a dynasty) of the Castro era. Paradoxically, the Seventh Party Congress (April 2016) still elected Raúl Castro and José Ramón Machado, First Secretary and Second Secretary of the PCC, respectively. While this means that the revolutionary veterans will still control key posts after 2018, it will also be the first time that the head of the Party and the head of the State is not the same person. All things considered, between the Sixth and the Seventh Party Congress -i.e. between 2011 and 2016- the nascent collegiality of the Cuban leadership was rein forced through measures that seek or serve “to prevent the rise of monocratic power”, to repeat Weber’s words.43 The Cuban case has thus moved closer to the institutional pluralism typical of the post-totalitarian ideal regime-type.44

Another new outcome of the Seventh Party Congress has been the rise of non-revolutionary veterans and non-FAR individuals to the core team -between 2008 and 2016 they grew from three to seven. Of them, six have careers in the PCC -of which four have been provincial Party leaders (Díaz-Canel, Mesa, López, and Boué). Thus, provincial party leadership has emerged as a desired promotion’s criterion to the top.45 Whether the PCC or the FAR will fill the future vacancies left by the revolutionary veterans will define the precise terms of the FAR-PCC partnership in the post-Castro era.

2. Ideology: from CPE to market socialism

Kong has classified the economic strategies of the surviving Communist systems into three different types: 1) ‘mono-transition’ (China and Vietnam), 2) ‘cautious reform’ (Cuba), and 3) ‘ultra-cautious reform’ (North Korea).46 For him, ‘mono-transition’ refers to a capitalist restoration under the same political regime -as opposed to East European countries that experienced the ‘dual transition’ of capitalist restoration and regime change. In contrast, the “cautious reform strategy seeks to alleviate the problems of the centrally planned economy (CPE) while resisting transformation towards a market economy”.47 Finally, the ‘ultra-cautious’ approach seeks “to restore the CPE by limited market measures“-hence the term refers to the stubbornness of an orthodox CPE.48

To build the definition of cautious reform in Cuba, Kong mainly refers to the economic reforms of the 1990s, though things have changed since then. According to Mesa Lago, 1991-1996 was indeed a period of ‘pragmatic’ policies, followed by a period of stagnation (1997-2003) and then by an ‘idealistic’ reversal of the reform (2003-2006).49 As for the presidency of Raúl Castro, the reformist path has not only resumed but also taken to a higher level. If the challenge for Cuban policymakers in the early 1990s was defined in terms of resisting the collapse of the Soviet Union (and its subsidies), since 2006 the self-imposed task has been to fix the economic model itself.

Raúl Castro has thus unleashed a new ‘pragmatic’ cycle of economic policy, the “strongest under the revolution.”50 Updating Kong’s words, it would be more precise to say that the Cuban regime has resumed the cautious reform by turning to market socialism ideas -an approach that, as I argue in this article, seeks to reconcile the CPE model with the market under the social ownership of the means of production.

In hindsight, Cuba’s ideological overhaul started with Raúl Castro’s first major speech as provisional head of state. On that occasion, he criticised how the country was run economically and sad that “structural and conceptual changes” were necessary.51 However, it was not until late 2009 that Raúl summarised his enterprise with a catchphrase: “the update of the Cuban economic model.”52 A few months later, he explained what he meant by “update” or “upgrade” (actualización, in Spanish):

We are convinced that we need to break away from dogma and assume firmly and confidently the ongoing upgrading of our economic model in order to set the foundations of the irreversibility of Cuban socialism and its development.53

This quote shows the compromise between change and orthodoxy articulated by the upgrade-of-the-economic-model formulation -a compromise between reform (“we need to break away from dogma”) and the respect of principles (“the irreversibility of Cuban socialism”). Although this tension has marked the presidency of Raúl Castro, it has functioned as a middle way solution between the two main economic visions within the elite: the Soviet-style one and the pro-market approach.54

To be sure, the largest expansion of non-state activity in socialist Cuba has occurred under Raúl Castro. For example, 71% of the workers employed in 2015 were state employees, in contrast to 80% in 2007.55 Since 2008, more than 1.58 million hectares of idle land have been transferred to non-state actors by January 2014, and the number of (mostly urban) self-employed workers has grown from 141 600 to half million in 2015.56 In a country with 6.2 million hectares of agricultural land and a total workforce of five million people,these changes are far from trivial.57

A major step in ‘updating’ the economy came in August 2010 when Raúl Castro announced the restructuring of the Cuban labour -self-employment being hailed as an alternative to soon-to-be-fired state employees.58 As a result, the self-employed were no longer portrayed as a necessary evil -top PCC leaders called them piranhas in the 1990s- and Granma even condemned such stigmatisation.59 At this point, “Raúl Castro and his associates obviously felt that they had arrived at a critical juncture and needed the endorsement of the highest party institution to strengthen their hand.”60 As a result, the call for the Sixth Party Congress was issued, with the Guidelines of Social and Economic Policy as the only document of the meeting agenda, which was first discussed in the grassroots inside and outside the Party.

The document had 291 paragraphs sketching future reforms in all sectors of the economy. Although “the document sometimes read like a laundry list that lacked strategic vision”,61 the rudiments of CPE-market love can still be perceived. The guideline that most explicitly elaborated the departure from CPE orthodoxy was the first one, which stated that in the new socialism of Cuba, “planning would take the market into account, influencing upon it and considering its characteristics.”62 Although this is rather a clumsy engagement with the market -treating it as an alien from outer space whose features are yet to be discovered- it epitomises the ideological hardships of the Party in coming to terms with the ‘update’ of Cuban socialism. In spite of these tensions, the second guideline was more confident in championing foreign investment, co-ops, private farmers, and self-employment as partners of “the socialist state enterprise” -defined as the “main form of the national economy”- in the quest for “efficiency”.63

The year after the Sixth Party Congress, and as a product of it, the then three-year-old upgrade-of-the-economic-model notion was entwined with a newborn concept: prosperous-and-sustainable-socialism, which was born in December 2012.64 The new notion was not fully shaped, however, until July 2013, when it was ingrained in the ideological framework advanced by Raúl Castro up to that point. The journey away from CPE orthodoxy had finally turned into a passage towards market socialism:

[T]he implementation of the Lineamientos […] approved by the Sixth Congress […] [is] the main task of all of us, because the preservation and development of socialism in Cuba depends on its success. A prosperous and sustainable socialism that ratifies the social property of the fundamental means of production and acknowledges the role of other, non-state, forms of management at the same time […] [A socialism that] reaffirms planning as an indispensable tool in directing the economy, without denying the existence of the market.65

The market had been pardoned, but not capitalism yet. The rise of self-employment was not the return of the bourgeoisie -i.e. a class of large proprietors of means of production, as opposed to small businesses. However, it is clear that times had changed. Non-state economic activity has never been this size under the Revolution.

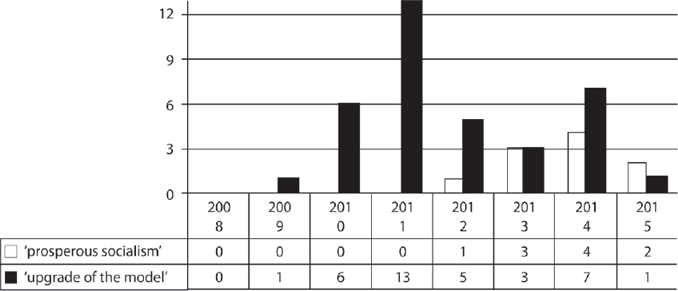

Figure 1 summarises the ideological vicissitudes of Cuba in Raúl Castro’s time in office. In hindsight, the period between 2006 and 2008 was in preparation for what would come next. Once Raúl was firmly in power, he championed the need to ‘update’ the economy with increasing confidence from 2009 to 2011, when his revolt reached its climax at the Sixth Party Congress. After this turning point, market socialism started to emerge and be acted upon according to the idea that prosperity was essential for the sustainability of Cuban socialism. In toto, the market was no longer the enemy, but a junior partner of central planning.

Sources: Own elaboration based on the analysis of all Raúl Castro’s speeches in Cuba (N=45) with NVivo software. It was counted the total number of appereances, by year, of two notions: ‘actualización del modelo económico cubano’ and ‘socialismo próspero y sostenible’.

Figure 1 Keywords of market socialism in Cuba, 2008-2015

The Seventh Party Congress kept on the market socialist path of ideological change but also acknowledged the slow pace of economic reform. Raúl Castro informed that only 21% of the Guidelines approved in 2011 had been fully implemented, 77% were in process, and 2% had not yet started.66 However, the 2016 Congress also approved a Conceptualisation Project of the Cuban Economic and Social Model of Socialist Development, which attempted to provide a long-term strategic direction to the reform process approved five years earlier.67 This document turned into Party doctrine the notion that “the strategic goal of the Model [that will emerge from the updating process] is to drive and consolidate the construction of a prosperous and sustainable socialist society.”68 In market socialist terms, the Conceptualisation Project also insisted: “the State recognises and integrates the market into the functioning of the system of planned direction of the economy.”69

IV. Explaining change

In the preceding section, I discussed how the leadership and ideology of the Cuban regime have changed during the presidency of Raúl Castro.

As I have been at pains to demonstrate, such changes can be defined as follows:

In this section I will discuss the relationship between both variations and their combined effect in the development of the Cuban regime within the same timeframe. A key claim of this article is that the rise of market-socialist ideology is, to a substantial extent, an effect of the decline of charismatic authority.

1. Regime-type development

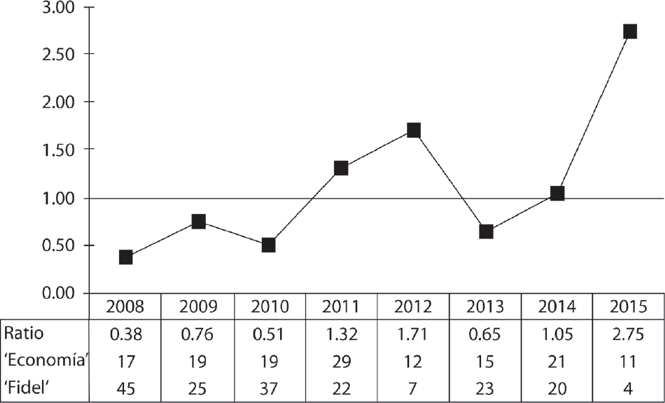

All Raúl´s speeches in Cuba are both transmitted on national TV and reproduced next day in Granma and/or Juventud Rebelde. Such speeches do not only intend to help Cubans make sense of political developments in the country, they are also the public face of the regime’s political moves. As “the mode of exercising authority” is conditioned by “the kind of legitimacy which is claimed”, it is not an insignificant political development when such claims vary in any regime.70 In the case of Cuba under Raúl Castro, I argue that there has occurred a variation in the legitimation strategy of the regime -a process indicated, albeit indirectly, by Figure 2.

Sources: Own elaboration based on the analysis of all Raúl Castro’s speeches in Cuba (N=45) with NVivo software. It was compared the quantity of total appeareances by year of two terms: ‘Fidel’ and ‘economía’.

Figure 2 Claims to legitimacy: charismatic-to-economical ratio, 2008-2015

Although Figure 2 only deals with only one person’s speeches, such a person is the head of the Cuban party-state -hence his political weight shall not be underestimated. I took all Raúl Castro’s speeches delivered in Cuba since 2008 and coded them according to key terms that stand for one or another legitimation strategy -“Fidel” for charismatic, and “economía” (economy, in English) for performance-based.71 Then I disaggregated this data by year and compared their relative incidence.

When the ratio shown in Figure 2 is < 1, it means that Raúl Castro mentioned ‘Fidel’ more times than the ‘economy’ in that single year in his speeches in Cuba. Using this index, it can be argued that before the 2011 Party Congress, charismatic claims prevailed over economic-based ones, while the opposite was true afterwards.72 In 2008, “Fidel” was mentioned 45 times and the “economy” 17 times. Meanwhile, in 2015 the numbers changed to 4 and 11, respectively. The exception to this trend was 2013, when Raúl’s presidency was renewed for five more (and final) years and the commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the attack to the Moncada barracks on the 26th of July took place. In this latter event, which marks the beginning of the Cuban revolution, Raúl praised his brother’s Fidel legacy to the socialist system, mentioning him on twelve occasions (from a total of twenty-three that year).73

As I have already discussed, Raúl Castro reformed the leadership before reforming the economy. It is significant, nonetheless, that this shift in political concerns was accompanied by a decline of the Fidel Castro’s persona in public discourse as a token of the state policies’ legitimacy. Thus, if Raúl asked the National Assembly permission to ‘consult’ everything with Fidel when the former was elected president in 2008, in his re-election -five years later- he reminded the National Assembly that state authority emanated from the ‘people’ according to the constitution.74

When compared to concerns on the succession question, the intensification of political concern on the economy suggests a political re-equilibration of the regime -i.e. the rise of market socialism took the toil of the decline of charismatic legitimacy. From a regime-type perspective, from 2006 to 2015 Cuba may be said to have changed from a charismatic early post-totalitarian regime to a maturing post-totalitarian one. This change can be analytically divided into two distinct stages:

from a ‘charismatic’ to a ‘typical’ early post-totalitarian regime; and

from the latter equilibrium to a maturing post-totalitarian regime.

Although both processes were empirically intertwined and coetaneous to some extent, each represents a different link in the political causal chain.

The first process is mostly related to the change in the type of leadership. As discussed, Raúl Castro’s answer to the succession problem after Fidel stepped down was the introduction of collegiality, as the approval of term-limits attest. Such a change marked the post-totalitarian normalisation of the Cuban leadership, as opposed to the typically totalitarian charisma. Therefore, the charismatic early post-totalitarian regime moved closer to the early post-totalitarian ideal type. As a result, the dissipation of charisma confronted the regime with the need to restore the deficit of legitimacy caused by the end of this old source. As early as 2009, Hoffmann had sensed that sooner or later the regime would have to sort out this predicament:

In the short run, the successor government can claim legitimacy based on the formal succession; in the medium term, however, it will have to seek new sources of support and legitimacy of its own. Economic performance will be crucial, and Raúl’s calls for economic reforms -however limited their implementation has been so far- seem to signal that the new leadership is very much aware of this.75

This argument can be taken a bit further. As the next generation of leaders -expected to take over in 2018- will not have the same legitimacy as the founding fathers of communist Cuba, let alone Fidel Castro, the upcoming biological end of the revolutionary veterans still in power has added an extra dose of difficulty to the problem of revamping the legitimacy of the regime. Hence Raúl Castro’s challenge has not only been to make his presidency stand on solid ground, but also to do so in such a manner that the new equilibrium of the political system will endure after he leaves. In other words, the revolutionary veterans -still the ‘inner circle’ of the leadership- have showed a strong interest in the survival of the system they devoted their life to. This biographical feature of the elite is perhaps what ultimately explains the rejection of capitalist restoration in Raúl’s economic reform. Of course, it is still to be seen how long this anti-capitalist limit will survive the “históricos” if it does.

The second process (maturation) is related to the change in the type of ideology. The new post-totalitarian equilibrium rapidly evolved from the early to the late stage, in which the regime was fully confronted with its economic failures -Fidel was no longer a safety belt. Raúl responded this problem with another switch: he gave up the freezing path he inherited from Fidel (the last ‘idealist’ cycle) and adopted a maturing direction. Raúl explicitly admitted that the economic focus of the Sixth Party Congress expressed the inner circle’s answer to the question of communist survival in Cuba:

The Sixth Party Congress should be, as a fact of life, the last to be attended by most of us who belong to the Revolution’s historical generation. The time we have left is short, the task that lies ahead of us is gigantic, and […] I think we have the obligation of taking advantage of the power of our moral authority among the people to trace out the route to be followed and resolve some other important problems. […] [W]e strongly believe that we have the elemental duty to rectify the mistakes that we have made all along these five decades during which we have been building socialism in Cuba.76

This quote, which confirms the extent to which the generational succession was linked to the problem of political survival, also reveals that the “moral authority” of the revolutionary veterans was being used to make Cuba stand on more solid ground after Fidel’s charisma was lost. It was perceived as necessary “to trace out the route to be followed”, which the Congress did by approving the economic Lineamientos that turned the initial relaxation of CPE orthodoxy into nascent market socialism.

Later, at the end of a 2012 Party Conference -with the new leadership and ideology already flourishing, Raúl assessed the new political situation: “the route has been traced.”77 Indeed, it had. Here the perspective of legitimacy helps to understand why the economic reform was necessary in the first place. It was needed, in Saxonberg’s terms, in order “to reach some sort of social contract with the population in order to induce it to ‘pragmatically accept’ that given certain external and internal constraints, the regime is performing reasonably well”.78 In other words, the turn to a performance-based legitimacy had been completed. The Sixth Party Congress thus resulted in Cuba definitely adopting a maturing path, as opposed to a freezing one of CPE obstinacy.

Cuba’s maturing path, nonetheless, differed from Saxonberg’s scheme in that there was no abandonment of socialist ideology, let alone a capitalist restoration (e.g. proper large-scale privatisations of means of production). Conversely, Cuba underwent an ideological renewal (an ‘update’ in Raúl’s words) in order to reconcile the socialist claims of the regime with economic performance (via the market), now turned into a naked test -i.e. the ‘Fidel card’ could no longer be played- to the regime’s legitimacy.

2. Cuba in (brief) comparative perspective

In order to appreciate the peculiarity (if any) of Cuba’s evolution, it makes sense to look at this case from a comparative perspective. To be sure, I do not intend to present an exhaustive comparison, which may well worth a specific endeavour. My aim is more modest: to place the characterisation advanced in this paper within the literature on the survival of contemporary communist systems in order to grasp the Cuban transition.

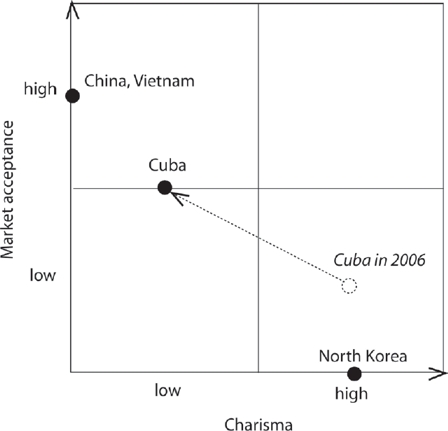

Figure 3 presents a comparison of the communist survivors at present, presupposing that only Cuba has changed its type of leadership and ideology since 2006. From this scheme, it follows that Cuba was more similar to North Korea than to China and Vietnam when Fidel Castro stepped down, but after eight years the opposite is true.

I do not mean that Kim Jong-Il (the North Korean leader at the time) was as ‘charismatic’ as Fidel Castro in the sense that both leaders had the same personal charm. All I assume is that both were treated as if their policies were infallible -i.e. as charismatic leaders. When Kim Jong-Il took over after his father died in 1997, his key claim to legitimacy was based on the premise that “the cause of the great leader” had been passed to him -in this case, the cause of the founding leader of North Korea’s regime, Kim Il-Sung.79 In other words, the North Korean solution to the “problem of succession” adopted “the conception that charisma is a quality transmitted by heredity”.80 As if to mimic Weber’s theory, the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea also explained that (when the time comes) the great leader (whoever she or he may be) is in charge of “designating the people’s leader who possesses extraordinarily personality and qualities as the successor”.81

In regards to ideology, although Cuba under Fidel oscillated between ‘idealist cycles’ and ‘pragmatic cycles’, the latter were tactical retreats as a rule. Hence the market was tolerated rather than accepted. In that sense, Cuba was closer to North Korea, although their actual economic approaches differed. By 2006, both countries had lived a period of economic reforms (North Korea in 1999-2005, and Cuba in 1991-1996), which were later curbed. In comparison, though, North Korea’s reforms had been more restrictive.82

As for China and Vietnam, I assume that upon the death of their founding leaders (respectively, Mao Zedong in 1976, and Ho Chi Minh in 1969) both regimes adopted sooner rather than later a collegial type of leadership. By 2016, Raúl Castro had established the same type of leadership, although it can be argued that as one of the founders of the regime, his presence still entails a dose of charismatic legitimacy as part of the históricos. If Kim Il-Sung had opted for a hereditary succession to avoid the messy post-Stalin and post-Mao successions,83 Raúl has tried to pre-empt any disorder by instituting collegiality within the históricos’ lifetime -an original route.

China and Vietnam eventually reformed the Soviet-style CPE through market reforms that later restored (a state-led) capitalism: China since 1979 led by Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping; and Vietnam since 1987-88 when the war with the United States was over (in 1975) and the confluence of Gorbachev’s perestroika and Deng’s reforms in China convinced the Vietnamese leadership of a change.84

While capitalism has been restored in China and Vietnam and the CPE is still firmly entrenched in North Korea, Cuba is located somewhere in between. Although Cuba’s current economic ideology is classified in Figure 3 as being closer to China and Vietnam than to North Korea, the difference between ‘medium’ and ‘high’ market acceptance is a substantial one for the latter presupposes a comeback of the bourgeoisie -an ideological limit that has not yet been lifted in the Caribbean case.

Raúl Castro has even implied that the difference of Cuba’s path from that of China and Vietnam is that the former has kept its communist -i.e. anti-capitalist- commitment:

The introduction of demand and supply rules is not at odds with the principle of planning. Both concepts can coexist and complement each other […] as has been successfully demonstrated in the processes of reform in China and renovation in Vietnam, as they call them. We have called it [our process] updating because we are not changing the key goal of the Revolution.85

I would then distinguish two degrees of maturation: ‘minor’ and ‘major’ -each one in turn informing and conditioning correlated economic strategies. Closer to the early post-totalitarian stage, a ‘minor’ maturation implies an ideological adjustment that has not broken the standard Marxist stance against the private property of means of production. If this principle is compared to a taboo then a ‘major’ maturation occurs when the taboo is broken, hence annulling the key Marxist anti-capitalist principle -as in contemporary China and Vietnam. If sparked as a regime’s response to the dissipation of charisma, any maturing trend, either minor or major, is another confirmation that charismatic decline has turned economic performance into the main concern of the regime -i.e. its main challenge to legitimacy.

V. Conclusions

According to Linz, in the work he co-authored with Stepan they limited “to distinguishing post-totalitarian regimes from both authoritarian regimes and the previous totalitarian regime. We did not enter into a detailed analysis of the change from totalitarianism to post-totalitarianism, although we did point to different paths and degrees of change.”86 Meanwhile, Saxonberg added a stringent framework to explain such a change and the rationale behind the different post-totalitarian paths. While I found his analytical contribution a powerful foundation to build on, I reapplied his framework to the Cuban case when doing so, in order to rectify a characterisation that I sensed was contradicted by reality.

I then discarded and endeavoured to replace Saxonberg’s explanation of the post-totalitarian evolution of Cuban communism. For him, Cuba (even under Raúl Castro) is a freezing post-totalitarian regime mixing patrimonial elements. I thus contended that, focusing on the period between 2006 and 2016, Cuba was neither patrimonial nor a freezing regime. On the one hand, I argued that the leadership of the Cuban regime had been charismatic, and then demonstrated that in the transition from Fidel to Raúl, the latter turned to collegiality. Then I established that market-socialist ideology had been ingrained in the Cuban approach to the CPE model, which is what I call a maturing path. Besides, I also demonstrated that the change in the type of leadership and ideology of the Cuban regime was caused by the re-equilibration of its claims to legitimacy.

In conclusion, Cuba under Raúl Castro has experienced a minor maturation after the Cuban regime entered the late post-totalitarian stage due to the loss of charisma. The ideological redefinition of admissible anti-capitalist economic policies managed to retain socialist claims to legitimacy (typical of the early stage) while developing market-based claims (typical of the late stage). This political tension is likely to mark the beginning of the post-Castro era, which is expected to start in 2018.

To position the contribution of this article within the existing literature, Table 2 proposes an updated classification of the surviving communist systems.

Table 2 Economic strategy and regime-type of surviving communist systems

| Economic strategy | Regime type | |

|---|---|---|

| China, Vietnam | Capitalist restoration | Maturing post-totalitarian |

| Cuba | * Market socialism | * Maturing post-totalitarian |

| North Korea | Centrally planned economy | Totalitarian (mixed with patrimonial rule) |

Sources: Apart from Cuba, the economic strategies and the regime-types were classified according to the characterisations of Kong and Saxonberg, respectively.87

* This is the argument developed in this article

In order to explain the evolution of China and Vietnam, Saxonberg had asserted that:

In some cases (China and Vietnam), the very economic success of reforms undermines the ideological legitimacy of the regime, since it has now become obvious that the reforms were based on the introduction of a capitalist market system, rather than on any kind of “socialist” alternative.88

As Saxonberg’s theory is based on the assumption that “any kind of “socialist” alternative” is impossible, he has only admitted two possible political paths:

[I]t seems communist countries have had to choose between either losing their ideological legitimacy by sticking to their ideology and having it fail, or giving up their ideology in order to meet their economic goals.89

This is what I call Saxonberg’s dilemma in section 2. The Cuban regime has escaped this dilemma as it neither has stuck to its ideology nor given up on it, which has implications when characterising the type of regime. On the one hand, its ideological departure from anti-market CPE precluded a freezing path. On the other, an orientation to performance-based legitimacy faithful to socialist ideology is still far from the current Chinese or Vietnamese capitalist maturing path. This is why Cuba’s peculiar path may be well defined as a post-totalitarian regime maturing in a market-socialist direction.

The Cuban regime, however, has curtailed the democratic potential of the market socialist path. In a rough comparison Cuba with the Yugoslav case, the ‘workers’ self-management’ effort is absent in the former. If the authoritarian path persists in Cuba, so will the threat of capitalist restoration.90 For example, the new co-op legislation has suppressed the democratic potential of the co-op’s General Assembly because its President is legally treated as if s/he were “a supreme figure” - perhaps “an extrapolation of the leadership’s schemes of the state sector.”91 Based on this legal ambiguity, some de facto privatisations have been disguised as conversions of small state businesses into urban co-ops, such as the “La Divina Pastora” restaurant in the tourist area of Morro Castle in Havana.92 However, whether this case of Cuban-style spontaneous privatisation is an isolated case or part of a wider phenomenon is still unknown and thus a (disquieting) matter of speculation.

To summarise, the market socialist approach seeks to reconcile the CPE with the market without restoring capitalism. I have also argued that Cuba belongs to the same type of regime as China and Vietnam, although it has a different economic strategy. Indeed, while these two Asian cases have long adopted a maturing path, in Cuba this kind of political development has just started.

Will Cuba catch up with China and Vietnam? This is, of course, a matter for future consideration, which the post-Castro leadership will most certainly undertake.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)