INTRODUCTION

Due to the growing demand for food, farmers need to implement measures to increase production. One of these measures is the use of chemical substances, such as herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, nematicides, and rodenticides, to protect their crops (FAO, 1997). Among the agrochemicals that are commonly used in crops near the rivers of Veracruz, Mexico, diuron, glyphosate, and paraquat are some of the most frequently used.

Diuron, 3- (3,4-dichlorophenyl) -1,1-dimethylurea, is used to control weeds and mosses in crops of bananas, pineapples, grapes, cotton, alfalfa, and sugar cane, as well as in ornamental species such as tulips and daffodils (Lewis et al., 2016). This herbicide is relatively stable in neutral waters and tends to become impregnated in suspended solids, contaminating groundwater. However, it has also been detected in surface waters of agricultural regions (INECC, 2021a). Diuron is considered extremely toxic to phytoplankton, moderately toxic to insects, and slightly toxic to amphibians and crustaceans (IRET, 2021).

Glyphosate, N- (phosphonomethyl) glycine, is a broad-spectrum herbicide used to control annual and perennial weeds, broadleaf weeds, and grasses. It is highly soluble in water, relatively volatile, and does not normally leach into groundwater. It is not persistent in soils but persists in aquatic systems under certain conditions. It is moderately toxic to birds, most aquatic organisms, earthworms, and honeybees (Lewis et al., 2016).

Paraquat, 1,1’-dimethyl-4,4’-bipyridinium, an herbicide of the bipyridyls group, is used for the control of glyphosate-tolerant weeds. It is moderately toxic to birds, slightly to moderately toxic to mollusks and zooplankton, slightly toxic to crustaceans, and not toxic to moderately toxic to fish, amphibians, and most insects; there is no toxicity to bees (INECC, 2021b).

In studies on diuron toxicity to crustaceans, an LC50 of 12 to 16 mg L-1 has been obtained (Turner, 2003; Koutsaftis & Aoyama, 2008; Alyürük & Çavaş, 2013; Shaalaa et al., 2015). Eisler (1990), in a study on paraquat, report a wide range of LC50 values, ranging from 1 to 100 mg L-1. Regarding glyphosate, Estrada-Jamillo (2012), using Litopenaeus vannamei (Boon, 1931) shrimp larvae, measured an LC50 of 0.5774 mL L-1.

In Mexico, there is little research on Potimirim mexicana (De Saussure, 1857), the species used in the bioassays in the present study. Bortolini et al. (2013) mention that this species is found from the north of the Gulf of Mexico to Panama, including Cuba, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico. Recently, Salas-De La Rosa (2018) reported that P. mexicana was the most abundant species, with 5 909 individuals on the coastline of the northern zone of the Veracruz Reef System during seven night collects of 12 h each one.

Due to the high density and, therefore, the potential for the use of P. mexicana in studies on the effects of agrochemicals on postlarvae, the objective of this study was to evaluate the response of P. mexicana postlarvae to exposure to diuron, glyphosate, and paraquat. The values of temperature, salinity, oxygen, pH, and total dissolved solids in the natural habitat of this species were determined and the proportion of this species in the estuary of the Jamapa River, Veracruz was evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

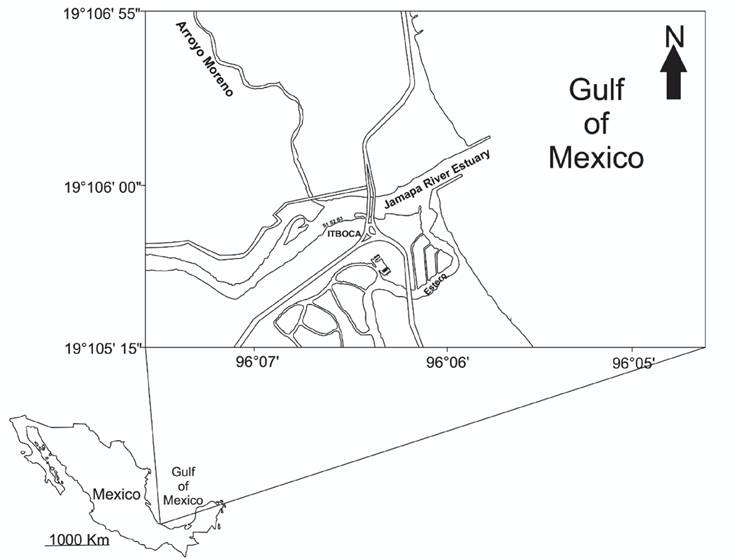

Study area. The Jamapa River has its origin within the states of Puebla and Veracruz. It joins the Cotaxtla River and later empties into the Gulf of Mexico in the municipality of Boca del Río, Veracruz. The estuary of the Jamapa River has other tributaries such as the Moreno stream and El Estero (the latter is the communication channel of the Mandinga Lagoon). The mouth of the Jamapa River discharges its waters to the Veracruzano Reef System National Park (PNSAV) (Liaño-Carrera et al., 2019). The Jamapa River basin is located between 18°45’-19°14’N and 95°56’-97°17’W. It has a warm subhumid climate, with an annual average temperature above 22°C; the average temperature of the coldest month is 18°C. Precipitation in the driest month ranges from 0 to 60 mm, with a rainy season in summer, receiving more than 55.3 mm of rainfall; in winter, only 50 to 10.2% of the total annual precipitation fall. There are six soil types, with regosol and vertisol being the most prevalent ones (Fuentes-Mariles et al., 2014). The level of the Jamapa River in its estuarine part has a micro-tidal modulation of approximately 2.0 m, with a semidiurnal, diurnal, and lunisolar component every 2 weeks (Salas-Monreal et al., 2019). As an estuary, it has a navigation channel in the southern part that generates important changes in its dynamics (Salas-Monreal et al., 2019). This channel produces strong currents of more than 0.5 m/s and a continuous exchange of brackish water with the ocean. On the southern side, the exchange of water from the river and the ocean is more continuous than on the northern side, where the water can remain static for periods longer than 24 hours due to low speed and the continuous supply of water from the Moreno stream. Pollution from urban wastewater discharges have increased the nitrogen concentration to approximately 11mlL-1, likewise, dissolved oxygen has decreased to concentrations less than 2 mlL-1 causing hypoxic conditions (Salas-Monreal et al., 2020) (Fig. 1).

Field work. Postlarvae of P. mexicana were collected in two samplings, one carried out in November and the other in March. For the collections, white light traps made with plastic boxes were used (Cházaro-Olvera et al., 2018). The samplings were nocturnal, considering the full moon phase. The traps were placed in three contiguous sites (Site 1, Site 2, Site 3) at 20:00 h on the first day of sampling and were removed at 8:00 h the next day (Fig. 1). From the in vivo sample, P. mexicana postlarvae were selected to perform the bioassays. The remaining samples were fixed with 70% alcohol and labeled with the date and place of sampling. At each site, the physicochemical parameters temperature (°C), salinity (ups), dissolved oxygen (mg L-1), pH, and total dissolved solids (ppm) were measured, using a previously calibrated Hanna® HI 9828 multiparametric device.

Laboratory work. The samples fixed in 70% alcohol were transported to the Crustacean Laboratory of the Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for separation and counting. For identification, a Motic model SMZ-168 optical microscope was used, following the original description by De Saussure (1857). Relative abundance, Shannon-Wiener diversity index, and Pielou equitability were obtained from each sampling (Magurran, 1988).

Bioassays. To perform the bioassays, water acclimatization was carried out 7 hours before the assays, using Elite 802® aerators. The values of the environmental factors were identical to those registered in the estuary of the Jamapa River. To carry out the bioassays, 10 postlarvae were used for each 500-mL plastic container following the criteria of Mohapatra & Rengarajan (1995).

The agrochemicals used were obtained from the following commercial brands: Karmex® (diuron 80% active ingredient), Cerillo SL® (paraquat 20% active ingredient). Herbipol® (glyphosate 36% active ingredient). Preliminary 96 h static bioassays were carried out to determine the concentrations range of the definitive bioassays. The concentrations of diuron were 1.75, 3.5, 6.96, and 14 mg L-1, those of paraquat were 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 mgL-1, and those of glyphosate were 101.25, 202.5, 405, 810, and 1,620 mg L-1. In every bioassay performed, three replicates were used. All treatments had a control without agrochemicals. Mortality readings were taken after 1, 2, 4, 8, 18, 24, 36, 48, and 96 hours of exposure (UC-Peraza & Delgado-Blas, 2012). For toxicity bioassays, the guidelines of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US-EPA, 2021) were considered, following the guide for ecological effect tests (US-EPA, 2016).

The toxicity analysis was carried out with the Probit method, and the mean lethal concentration (LC50) was determined with the statistical program Minitab Version 18.1 (Minitab ©, LLC, State College PA, USA), and the 95% confidence interval was obtained. To obtain the relative abundance, Shannon-Wiener diversity index, and Pielou equitability, the PAST software version 3.26 was used (Harmer et al., 2001).

RESULTS

Dissolved oxygen ranged between 6 and 7 mgL-1, the pH between 8 and 9, and temperature between 26 and 27° C, during the study period. The levels of total dissolved solids were 700 and 1,500 ppm in March and November, respectively. Salinity ranged between 0.70 - 16 ups in November and March, respectively (Table 1A). In the bioassays the values of the physicochemical parameters were similar to the parameters registered during the sample collection (Table 1B).

Table 1 Environmental factors. A, environmental conditions for the collection of Potimirim mexicana from Jamapa River estuary, Boca del Río, Veracruz; and B, environmental conditions in the laboratory during bioassays.

| A | ||

| Environmental factors | March | November |

| Dissolved Oxygen (mg/L) | 6.93 ± 0.12 | 5.79 ± 0.12 |

| pH | 8.54 ± 0.38 | 7.81 ± 0.21 |

| Temperature (°C) | 26.68 ± 0.12 | 26.08 ± 0.92 |

| Total dissolved solids (ppm) | 732.5 ± 34.44 | 1443.33 ± 65.91 |

| Salinity (psu) | 15.35 ± 0.65 | 0.89 ± 0.19 |

| B | ||

| Environmental factors | March | November |

| Dissolved Oxygen (mg/L) | 6.82 ± 0.12 | 6.73 ± 0.15 |

| pH | 8.61 ± 0.12 | 8.71 ± 0.32 |

| Temperature (°C) | 27.01 ± 0.15 | 27.38 ± 1.09 |

| Total dissolved solids (ppm) | 722.8 ± 175.33 | 1252.66 ± 106.69 |

| Salinity (psu) | 0.72 ± 0.18 | 13.99 ± 5.48 |

In total, 29,769 organisms of six taxa were collected: postlarvae of Macrobrachium acanthurus(Wiegmann, 1836), M. olfersii (Wiegmann, 1836), and Potimirim mexicana (de Saussure, 1857), megalopas of Callinectes sapidus Rathbun 1896, and Armases ricordi (H. Milne Edwards, 1853), and zoeas of the Brachyura Latreille, 1802 (Table 2). Based on the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test, the abundance data in March followed a normal distribution (P < 0.05), whereas in November, this was not the case (P > 0.05). Given the above, the Mann-Whitney test was applied, and no significant differences were found (U = 14; P = 0.589) for abundance between the sampling months. This leads us to infer that the structure of the association remains unchanged in the cold season. A total of 12,827 postlarvae of P. mexicana were obtained; the highest abundance was recorded in November with 8,967 postlarvae. Diversity ranged from 1.55 to 1.77 bits*individual-1 in March and November, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2 Association of decapod crustaceans from Río Jamapa estuary, Boca del Río, Veracruz.

| Taxa | March | November | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Postlarvae of Macro brachium acanthurus | 181 | 556 | 737 |

| Postlarvae of Macrobrachium olfersii | 567 | 1788 | 2355 |

| Postlarvae of Potimirim mexicana | 3860 | 8967 | 12827 |

| Megalopae of Callinectes sapidus | 559 | 1057 | 1616 |

| Megalopae Armases ricordi | 6075 | 6051 | 12126 |

| Zoeae of Brachyura | 33 | 75 | 108 |

| Total | 11275 | 18494 | 29769 |

| Shapiro-Wilk W | 0.03 | 0.11 | |

| Mann-Whitney (March-November) | 0.589 | ||

| Diversity (bits/individual) | 1.55 | 1.77 | 1.68 |

| Equitability (J) | 0.6 | 0.68 | 0.65 |

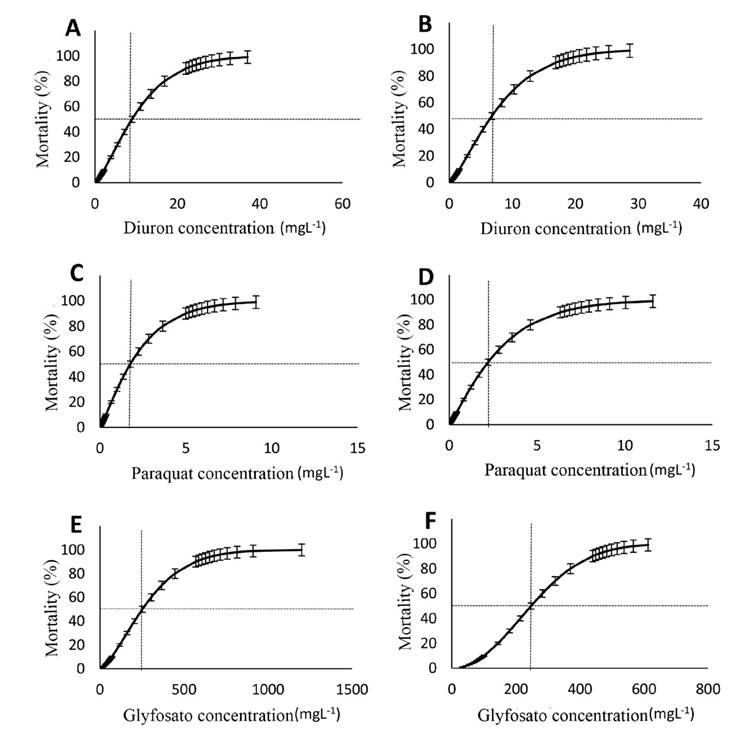

When analyzing the response to herbicides, a mortality of 100% was obtained for P. mexicana with the maximum concentration of 28 mgL-1 of diuron in both months. Applying the Probit analysis, a diuron LC50 of 8.98 mg L-1 was found for P. mexicana at 96 h in March, with a range of 7.94 to 10.06 mg L-1 (Fig. 2A). For November, an LC50 of 6.76 mg L-1 was obtained, with a 95 % confidence interval of 5.94 to 7.59 mg L-1 (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2 Toxicity of agrochemicals to postlarvae of Potimirim mexicana. Diuron, Paraquat and Glyphosate. (March: A, C, E), (November: B, D, F)

With the maximum concentration of 10 mgL-1 of paraquat, 100% mortality of P. mexicana was recorded for both samplings. With Probit analysis, a paraquat LC50 of 1.76 mg L-1 was found at 96 hours for March, with a 95 % confidence interval of 1.51 to 2.01 mg L-1 (Fig. 2C). For November, the LC50 was 2.21 mg L-1, with a 95% confidence interval of 1.91 to 2.51 mg L-1 (Fig. 2D).

For the maximum glyphosate concentration of 1,620 mg L-1, 100% mortality of P. mexicana was recorded for both samplings. Based on the Probit analysis, a 96-hour glyphosate LC50 of 252.05 mg L-1 was obtained at 96 hours for March, with a 95% confidence interval of 221.05 to 282.55 mg L-1 (Fig. 2E). For November, the LC50 was 247.71 mgL-1, with a 95% confidence interval of 224.18 to 271.15 mg L-1 (Fig. 2F).

DISCUSSION

The dissolved oxygen concentration values obtained here are similar to those recorded by Castañeda-Chávez et al. (2017) and Salas-Monreal et al. (2020), who found between 5 and 6 mgL-1 in the study area during the cold front season. As response to the decrease in temperature, the dissolved oxygen increases due to intense winds that mix the water column (Riverón-Enzástiga et al., 2016). In the present study, the values obtained fall within the range reported previously, suggesting that the water quality of the Jamapa River allows the presence of Potimirim postlarvae (DOF, 1989); the recommended value for the protection and proper development of aquatic life is 5 mgL-1.

The pH values are like those found in the Jamapa River basin (Houbron, 2010). The standard range established is 6.5 to 8.5 units for drinking water (NOM, 1994), indicating that in the study area, a buffer effect is present, avoiding water (Bates, 1973); this can be related to the intermediate stability obtained according to the Shannon-Wiener diversity values.

The temperature was slightly higher than that found by Jasso-Montoya (2012) and Avendaño-Álvarez (2013), Contreras-Espinoza (2016), and Castañeda-Chávez et al. (2017), who registered values between 23 and 24°C. However, different species of the Atydae family develop adequately at temperatures around 27°C (Abele & Blum, 1977), which is consistent with the findings of the present study.

Total dissolved solids were close to or exceeded the maximum permissible limit of 1,000 ppm (NOM, 1994), potentially resulting in a significant carry-over of herbicides to the estuary of the Jamapa River (Aragón-López et al., 2017).

Regarding salinity, values between 6 and 20 ups have been registered at the mouth of the estuary of the Jamapa River (Aké-Castillo, 2016; González-Vázquez et al., 2019). Likewise, González-Vázquez et al. (2019) mention that values below 2 ups were recorded in September, which is consistent with that obtained in the present study. Salas-Monreal et al. (2020) mention that in the estuary of the Jamapa River, salinity is higher than expected for a river and lower in the estuary, most likely because of the interaction of the Jamapa River with the mouth of Arroyo Moreno, which continuously provides fresh water to the system.

The high abundance levels of Brachyura shrimp, megalopa, and zoea postlarvae is related to the species’ breeding season, their migratory character, and their high tolerance to changes in environmental factors (Williams, 1984; Álvarez et al., 2011). Salas de la Rosa (2018) also found high abundance values on the coastline of the northern part of the port of Veracruz after the rainy season.

With diversity values of 1.5 to 1.8 bits*individual-1, it can be considered that the community of larvae and postlarvae of the Boca del Río Veracruz estuary has an intermediate stability. In this regard, Stub et al. (1970) mention that diversity values of less than 1 are found in places with low environmental stability, values of 1 to 2 in places with intermediate stability, and values greater than 3 are found in places with stable environmental conditions.

When analyzing the response to herbicides, Shaalaa et al. (2015) found that for Artemia salina (Linnaeus, 1758) nauplii, the diuron LC50 was 6.00 mg L-1. Alyürük & Çavaş (2013) found a diuron EC50 value of 12.01 mg L-1 for A. salina larvae, whereas Koutsaftis & Aoyama (2008) found a diuron LC50 for A. franciscanaKellog, 1906, of 12.5 mg L-1. With an active ingredient of 80 to 95%, Turner (2003) found an LC50 of 8.4 mg L-1 for Daphnia magnaStraus, 1820. Jinlin, et al. (2020) report that the acute toxicity of diuron (48 h) toDaphnia magnawas 17.1 mg·L-1 and Sipcam Pacific Australia (2020) mentions that acute toxicity for the same species is 6.3-13 mg L-1. Thus, the LC50 obtained for P. mexicana is within the values commonly observed.

Regarding paraquat, Eisler (1990) found an LC50 for Procambarus clarkii (Girard, 1852) of 1.4 mg L-1 and for Gammarus fasciatus Say, 1818 of 11 mg L-1. Gil-Diaz et al. (2021) obtained 0.31 µl L-1, with a 95% confidence interval with a lower limit of 0.26 µl L-1 and an upper limit of 0.35 µl L-1 for the M. olfersii shrimp. Likewise, Barbosa et al. (2014) mentions that Daphnia similis had LC50 of 4 mg L-1 and Macrobrachium sp. of 5 mg L-1. The lethal concentrations obtained in this study for P. mexicana were within the range previously reported.

For glyphosate, a wide range of the lethal concentration for crustaceans has been reported. For example, Herrera et al. (2016) obtained an LC50 range from 5.3 to 930 mg L-1 for Daphnia spp. and Gammarus spp.; for different species of fish, 10 to 1,000 mg L-1 in glyphosate have been found in commercial formulas (Folmar et al., 1979; Morgan & Kiceniuk, 1992). Ashoka-Deepananda et al. (2011) report that the LC50 value for Australian native freshwater shrimp, Paratya australiensisKemp, 1917, was greater than 700 mg L-1 of glyphosate. In Daphnia magna Straus, 1820 the LC50 was 82.5 mg L-1 (Melnichuk et al. 2007). In the present study, the LC50 for P. mexicana was in the lower quartile with respect to previously mentioned values (221.05 mg L-1).

In conclusion, the average abundance values of larvae and postlarvae collected in the present study are consistent with those of larvae found in other studies in the mouth of the Jamapa River in the cold front season. The environmental conditions in the Boca del Río estuary, Veracruz, allow the presence of postlarvae of Potimirim mexicana, with a high ecological valence.

Based on the community diversity of larvae and postlarvae of the Boca del Río Veracruz estuary, an intermediate stability can be considered. For P. mexicana, the minimum LC50 values were 5.94 mg L-1 for diuron, 1.51 mg L-1 for paraquat, and 221.05 mg L-1for glyphosate. These values are consistent with those obtained by other authors for different species of crustaceans. Potimirim mexicana postlarvae are sensitive test organisms to evaluate the toxicity to diuron, paraquat, and glyphosate. Taking into consideration the relevant ecological role of P. mexicana due to its high abundance in rivers, estuaries, and coastal marine environments, its inclusion in ecotoxicological studies is recommended.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)