INTRODUCTION

Insomnia is defined as a persistent difficulty in sleep onset, duration, consolidation and/or quality that occurs despite the existence of adequate circumstances and opportunity to sleep, is accompanied by a significant level of impairment in social development areas, occupational, educational, academic, or behavioral functioning (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014). Nocturnal symptoms are characterized by difficulty falling asleep when someone goes to bed, difficulty staying asleep, early morning awakening with inability to return to sleep, and unrefreshing sleep (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The main daytime symptoms of insomnia are fatigue, drowsiness, impaired memory, attention, and concentration, reduced academic or occupational productivity, altered mood, difficulty in decision-making, low motivation, and impaired social and emotional functioning (Mai & Buysse, 2008; Nami, 2014).

The cognitive model of insomnia (Harvey, 2002) indicates that repetitive negative thoughts about sleep would increase the level of cerebral cortical activation, leading to a state of hyper alertness and difficulty falling asleep. At the same time, these persistent thoughts would be accompanied by dysfunctional concerns and beliefs about sleep, selective attention and monitoring of stimuli that can impair sleep, counterproductive safety behaviors (e.g., spending more time in bed, daytime naps), which would propitiate the chronic evolution of insomnia.

Ruminative thinking or rumination is a set of repetitive, recurrent negative thoughts that focus attention on oneself, emotions, worries, and stressful or negative experiences (Watkins, Moberly, & Moulds, 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema & Watkins, 2011). Evidence exists on the relationship between rumination and insomnia; previous research has reported an increase in sleep latency time, poor sleep quality and reduction in sleep efficiency in insomniac patients compared to healthy subjects (Galbiati, Giora, Sarasso, Zucconi, & Ferini-Strambi, 2018), young adults with depressive symptoms (Pillai, Steenburg, Ciesla, Roth, & Drake 2014) and graduate students (Van Laethem, Beckers, van Hooff, Dijksterhuis, & Geurts, 2016). On the other hand, ruminative thoughts have been found to reduce deep sleep time and increase awakenings throughout the night (Gregory et al., 2011). In turn, rumination focused on the insomnia consequences would increase during the day, while anticipated concerns about difficulty sleeping would be more prominent at bedtime (Ong & Tu, 2020; Lancee, Eisma, van Zanten, & Topper, 2017).

Previous research has used different scales to assess rumination in patients with sleep problems, such as the Symptom-Focused Rumination Subscale (Bagby, Rector, Bacchiochi, & McBride, 2004) from the Response Styles Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), Ruminative Response Scale (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), Rumination Reflection Questionnaire (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999) and Ruminative Thought Scale Questionnaire (Brinker & Dozois, 2009), however, these instruments do not contain specific questions about ruminative thoughts, diurnal symptoms and insomnia consequences.

Carney, Harris, Falco, & Edinger (2013) designed the DISRS scale to identify daytime ruminative thoughts in insomniacs. It consists of 20 items that are divided into three subscales: 1. level of motivation and cognitions about sleep, 2. negative affective state, and 3. tiredness. DISRS was originally written in English, it has been applied to the general population in the United States (Tutek, Gunn, & Lichstein, 2021) and has been translated into other languages such as Italian (Palagini, 2015) and Norwegian (Norwegian Association for Cognitive Therapy, s.f.).

Some researchers suggest differentiating between repetitive ideas associated with various psychiatric disorders and repetitive thoughts linked to fatigue and tiredness. These last two clinical manifestations are characteristic of rumination associated with insomnia (Carney, Harris, Moss, & Edinger, 2010; Tutek et al., 2021).

The main purpose of this research was to determine the psychometric properties (internal consistency, construct validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity) of the DISRS scale in a sample of participants who attended a general medicine outpatient clinic and live in Mexico City.

METHOD

Subjects and place

The DISRS scale was administered to a sample comprising patients and relatives seeking outpatient general medicine care at a T-IIII health center located in the south of Mexico City (n = 102). The sample size was defined using the rule of five participants for each questionnaire item, 5 × 20 = 100 (Streiner et al., 2003) and convenience sampling was used. Our inclusion criteria were people aged 18 years or older, who could read and write, who agreed to participate voluntarily and did not have cognitive deficits or any other medical condition that prevented them from answering the questionnaire. People who did not wish to participate (n = 7) or failed to complete the questionnaire (n = 5) were excluded from the study.

Exclusion criteria: Participants < 18 years old, people with a serious medical or psychiatric illness such as parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, dementia of any etiology, an obvious intellectual disability. Those who did not want to participate in the study complete questionnaire were also excluded.

Instruments

Daytime Insomnia Symptom Response Scale (DISRS)

This scale comprises a 20-item, self-administered questionnaire developed and validated (Carney, 2013). Subjects are asked how often they engage in a series of behaviors when they feel tired and sleepy. Scores range from 20 to 80 points and there is no defined cut-off point: the higher the scores on the scale, the higher the level of ruminative thinking. In the validation process, the authors thought that this instrument had good internal consistency (α = .93, -.94) and through exploratory factor analysis, they identified three dimensions: 1. cognitive/motivational (items: 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 17, 18), 2. negative state (items 1, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 19) and 3. tiredness (items 2, 13, 16, 20). These three factors explained 58.12% of the total variance.

Spanish translation of the DISRS scale

The Spanish translation of the DISRS scale was undertaken by the main author, after which a bilingual group of three experts reviewed the translation of the scale into Spanish. A pilot test was conducted with ten insomniac patients to assess the level of understanding of the questions and the time it took to fill out the questionnaire.

An independent bilingual expert was asked to translate our Spanish version of the DISRS (back translation) into English. The same bilingual group subsequently reviewed the English translation done by the expert and considered that the Spanish version was similar to the original scale.

Ruminative Response Scale (RRS)

The RRS assessing two components of rumination: reflection, which refers to behaviors related to the analysis of the difficulties experienced, and reproach, which involves repetitive thoughts focused on psychological discomfort and negative self-evaluation. The RRS response options are provided on a four-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 22 to 88 points. The higher the score, the higher the level of ruminative thinking (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). The Mexican Spanish version was validated; the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient obtained was .93, for the reflection subscale α = .77 and for the reproach subscale α = .78 (Hernández-Martínez, García Cruz, Valencia Ortiz, & Ortega Andrade, 2016).

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)

This instrument was designed to screen for insomnia symptoms (Bastien, Morin, Ouellet, Blais, & Bouchard, 2004). It consists of seven self-assessment questions that explore the level of severity of insomnia, satisfaction with the current sleep pattern, the level of dysfunction attributed to the sleep problem, and the degree of concern caused by insomnia. The answers options are provided on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Not at all to 4 = extremely), with scores ranging from 0-28. A score of 0-7 indicates that there is no insomnia; 8-14 points correspond to mild insomnia; 15-21 points indicates moderately severe insomnia, and 21-28 points suggests severe insomnia. The internal consistency of this instrument is adequate, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .82 to .92 (Fernandez-Mendoza et al., 2012; Gagnon, Bélanger, Ivers, & Morin, 2013).

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ)

This scale comprises 16 items assessing the general tendency to worry rather than being restricted to one or two situations. The PSWQ has been administered in general and clinical population studies. It contains Likert answer options, is scored from 1 to 5 points, and five of the items: 1, 3, 8, 10 and 11 are reverse scored. However, there are versions of this scale in which all the questions are direct and there are no reverse items (Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec 1990). PSWQ was validated in the Mexican population, finding an internal consistency of α = .917 (Padros, González, Martínez, & Wagner, 2018).

Procedure

Patients and family members were invited to participate in the study, while they were in the waiting room of the health center. If they agreed to participate, they were informed that they had to answer a series of questionnaires, including the DISRS. Sociodemographic and clinical variables such as age, gender, marital status, educational attainment, employment status, current health problems, and insomnia were also evaluated.

Before the information was collected, written informed consent was requested from all those who had voluntarily agreed to participate in the study.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the general principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (Mazzanti, 2011). Approval was obtained from Research Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Psychiatry Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz (Instituto Nacional de Psiquiatría Ramón de la Fuente Muñiz, INPRFM; with agreement number CEI-010-20170316).

Statistical analysis

The STATA 16.1 program was used for the statistical analysis. The mean and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables. In the case of categorical variables, frequencies, percentages, and total scores were calculated for each participant. The Student’s t test was used to compare the means of our variables and determine whether there are differences between men and women.

Internal consistency analysis was performed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the items and the total scale. To validate the questionnaire, an exploratory factor analysis was performed using the principal components method with varimax rotation and eigenvalues greater than one to assess the construct validity of the DISRS. Correlations with the other scales (ISI, RRS, and PSWQ) were subsequently calculated and lastly discriminant validity was evaluated through standardized canonical coefficients (SCC) and cases were classified according to the high and low DISRS scores.

RESULTS

102 subjects were included, 67 of which are women (65.7%) and 35 men (34.3%). Table 1 shows their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. We found a slight difference between men and women in the average of the scales administered, DISRS (x̄ = 35.27, SD = 11.32 vs. x̄ = 30.94, SD = 9.37), ISI (x̄ = 8.59, SD = 6.07 vs. x̄ =7.6, SD = 5.97), RRS (x̄ = 40.43, SD = 12.19 vs. x̄ =36.4, SD = 13.22), PSWQ (x̄ = 41.11, SD = 14.51) vs. x̄ = 37.11, SD = 15.11).

Table 1 Description of sociodemographic and clinical variables

| Variables | n (%) | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18-25 years 26-40 years 41-60 years > 60 years |

26 (25.5) 45 (44.1) 27 (26.5) 4 (3.9) |

15 (22.73) 28 (42.42) 21 (31.82) 2 (3.03) |

11 (30.56) 18 (49.98) 5 (13.9) 2 (5.56) |

| Sex | 102 (100) | 66 (64.71) | 36 (35.29) |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Elementary Junior high Senior high Undergraduate degree Other |

9 (8.8) 33 (32.3) 36 (35.3) 18 (17.7) 6 (5.9) |

7 (10.61) 19 (28.79) 25 (37.88) 9 (13.64) 6 (9.09) |

2 (5.56) 15 (41.67) 11 (30.56) 5 (13.89) 3 (8.34) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single Married/living together Divorced Widowed |

35 (34.3) 60 (58.8) 5 (4.9) 2 (1.9) |

20 (30.3) 43 (65.15) 2 (3.03) 1 (1.52) |

15 (41.67) 18 (50) 2 (5.56) 1 (2.78) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed Unemployed |

59 (57.9) 43 (42.1) |

31 (46.97) 35 (53.03) |

27 (75) 9 (25) |

| Health problems | |||

| Yes No |

29 (28.4) 73 (71.6) |

20 (30.3) 46 (69.7) |

8 (22.22) 28 (77.78) |

| Insomnia severity index (ISI) | |||

| Mean | 8.2 (SD:6.0) | 8.59 (6.07) | 7.6 (5.97) |

| DISRS scale | |||

| Mean | 33.8 (SD:10.9) | 35.27 (11.32) | 30.94 (9.87) |

| RRS scale | |||

| Mean | 39.1 (SD:12.6) | 40.43 (12.19) | 36.4 (13.22) |

| PSWQ scale | |||

| Mean | 39.6 (SD:14.8) | 41.11 (14.51) | 37.11 (15.11) |

Notes: DISRS: Diurnal Insomnia Symptoms Associated with Rumination Scale; RRS: Ruminative Response Scale; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; PSWQ: Penn State Worry Questionnaire; SD: Standard Deviation.

Internal consistency: The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the DISRS scale was .93. This result indicates that there is a high consistency between the items comprising this scale. Table 2 shows the Pearson correlations of all the DISRS items. In general, the 20 questions achieved Cronbach’s alpha values above .90. The internal consistency of the three subscales was slightly lower than the total result. The negative affective state subscale had a consistency of α = .89, the cognitive/motivational subscale had a consistency of α = .85 and the fatigue subscale had a consistency of α = .72.

Table 2 Pearson correlation coefficients between items and total scale

| Item |

Item-test

correlation |

Item-test

correlation |

Average

inter-item covariance |

Cronbach’s

Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISRS 1 DISRS 2 DISRS 3 DISRS 4 DISRS 5 DISRS 6 DISRS 7 DISRS 8 DISRS 9 DISRS 10 DISRS 11 DISRS 12 DISRS 13 DISRS 14 DISRS 15 DISRS 16 DISRS 17 DISRS 18 DISRS 19 DISRS 20 |

.6395 .5669 .6461 .7676 .6829 .5574 .6459 .7454 .7651 .7398 .8226 .7252 .6984 .7813 .6681 .6611 .6968 .5936 .5490 .6915 |

.6020 .5175 .5975 .7341 .6437 .4946 .5992 .7080 .7347 .7026 .7966 .6865 .6564 .7506 .6240 .6154 .6620 .5377 .4911 .6505 |

.2887 .2890 .2821 .2766 .2835 .2848 .2831 .2768 .2798 .2779 .2746 .2788 .2799 .2770 .2822 .2821 .2849 .2841 .2873 .2814 |

.9361 .9374 .9362 .9337 .9353 .9384 .9361 .9341 .9338 .9342 .9326 .9345 .9351 .9334 .9356 .9358 .9352 .9374 .9381 .9352 |

| .28178 | .9385 |

Validity: The exploratory factor analysis was based on the results published by the authors (Carney et al., 2013) who identified three factors: 1. cognitive-motivational, 2. negative affect and 3. tiredness. Since all the items on the scale achieved communalities of over .30, they were included in the factor analysis. A 3-component solution was obtained, explaining 59.5% of the variance, a large part of the total variance is explained by cognitive-motivational factor with 47.21%, while the other two factors, negative state, and fatigue, explain 6.56% and 5.76%, respectively. The Kayser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sampling adequacy index was .92 and the Barlett’s sphericity coefficient proved to be statistically significant (Chi square: 1143.41, gl: 190 p = .001). Table 3 shows the factorial loads of each item with the varimax rotation.

Table 3 Rotated component matrix and item factor loads

| Items | Components | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

|

Cognitive-

motivational |

Affective

state |

Tiredness | ||

| 1 | They think “I won’t be able to work because I feel very bad.” | .523 | .141 | .446 |

| 2 | They think about their feelings of tiredness. | -.015 | .710 | .352 |

| 3 | They think about how difficult it is to concentrate. | .167 | .255 | .780 |

| 4 | They think about how demotivated they feel. | .750 | .326 | .189 |

| 5 | They think about how cloudy or confused their thoughts are. | .695 | .233 | .185 |

| 6 | They think about how everything requires more effort than usual. | .065 | .299 | .685 |

| 7 | They think “Why can’t I get ahead?” | .722 | .140 | .192 |

| 8 | They think how sad they feel. | .681 | .290 | .266 |

| 9 | They think how they do not feel they want to do anything or any activity. | .594 | .394 | .315 |

| 10 | They think about their feelings of pain. | .486 | .575 | .203 |

| 11 | They think how bad they feel. | .472 | .680 | .270 |

| 12 | They think how difficult it is to keep their mind on a task. | .604 | .055 | .588 |

| 13 | They think about how tired they feel. | .263 | .453 | .550 |

| 14 | They think, “I can’t get rid of this feeling.” | .718 | .390 | .182 |

| 15 | They think about how irritable they feel. | .564 | .531 | -.005 |

| 16 | They think about how sleepy they feel. | .232 | .687 | .247 |

| 17 | They think, “It seems I can’t pay attention.” | .465 | .129 | .641 |

| 18 | They think, “I am forgetful.” | .363 | .246 | .415 |

| 19 | They think, “I can’t be near people when I feel like this.” | .302 | .490 | .119 |

| 20 | They think. “I don’t have enough energy to get through the day.” | .361 | .601 | .233 |

Note: Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization.

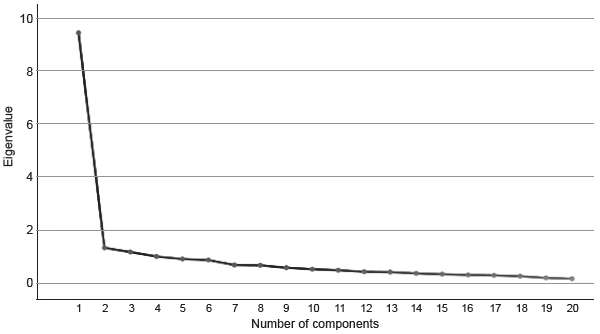

This criterion was confirmed by the sedimentation graph (Figure 1), which shows that the eigenvalues begin to form a straight line after the third main component. Accordingly, the remaining principal components only explain a small proportion of the variability, close to zero, and are unimportant.

Regarding the convergent validity of the scale, we calculated the correlations between the variables of interest (Table 4). As expected, the DISRS Scale correlated positively with insomnia symptoms (r = .648; p < .01), worries (r = .732; p < .01), and ruminant responses (r = .778; p < .01).

Table 4 Correlations with other study variables

| DISRS | RRS | ISI | PSWQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISRS | 778** | .648** | .732** | |

| RRS | .778** | .714** | .670** | |

| ISI | .648** | .714** | .610** | |

| PSWQ | .732** | .670** | .610** | |

| DISRS cognitive | .938** | .767** | .555** | .667** |

| DISRS negative state | .898** | .723** | .715** | .663** |

| DISRS tired | .853** | .573** | .489** | .659** |

| RRS depression | .809** | .971** | .696** | .680** |

| RRS reflection | .569** | .840** | .633** | .489** |

| RRS brooding | .698** | .911** | .616** | .632** |

**Correlation is significant at 0.01 (bilateral).

Correlations between the items and the total scale were significant (p < .05), meaning that the items correspond to each factor differentially. Correlations range from .19 to .76 between the items. Correlations between the total DISRS score and the cognitive-motivational dimensions (r = .938, p < .01), negative state (r = .898, p = < .01) and tiredness (r = .853, p < .01) were statistically significant and with the subscale of depressive symptoms of RRS (r = .809, p < .01). Additionally, the highest correlations of the ISI scale were found with the RRS scale (r = .714, p < .01) and the negative state subscale of the DISRS (r = .715, p < .01), with the rest of scales, the correlations were moderate.

For discriminant validity, the total scores of the ISI, PSWQ and RRS scales were included in the analysis as independent variables, while the dependent variable was represented by the total scores of the DISRS. The result of the Box M test (33.409, p < .05) confirms that the variance-covariance matrices are different; a single discriminant function was determined with an eigenvalue of .638 and a canonical correlation of .624. Wilks’ Lambda statistic has a moderate value (λ = .611, p < .05). Standardized canonical coefficients (CCE) helped identify the variables with the greatest weight in the predictive model, yielding the following equation of coefficients: discriminant function (FD) = -3.359 + .33 PSWQ + .89 ISI + .33 RRS. Lastly, the discriminant function correctly classified 77 cases (75.5%) based on worries, insomnia symptoms, and ruminant responses unrelated to sleep difficulty. Individuals with high levels of rumination associated with insomnia had more worries and an unreflective, reproach-oriented thinking style (Table 5).

Mental health: We did not find any statistically significant differences when the average of the scales administered between women and men was compared. DISRS: t (99) = -1.909, p = .059; ISI: t (99) = -.786, p = .434; PSWQ: t (99) = 1.297, p = .198; RRS: t (99) = -1.538, p = .127.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The purpose of this study was to analyze the psychometric properties of the DISRS scale in a Mexican population sample. The internal consistency, construct validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were determined.

The total scores of the scales administered were slightly higher in the group of women than in that of men; it is striking that over half the participants were female (64.71%). The role played by certain sociodemographic variables in mental health has been reported in previous research. Our results coincide with the evidence on the vulnerability of women to suffering from insomnia, rumination, and excessive worry in relation to men (Krystal, 2003; Johnson & Whisman, 2013).

The version of the DISRS scale translated into Spanish had good internal consistency. The three cognitive-motivational factors, negative state, and tiredness correlated with each other. A certain tendency can be observed to present higher correlation coefficients in the dimension to which the items correspond. The rotated component factor analysis revealed three factors: cognitive-motivational (9 items), negative state (6 items), and fatigue (5 items), which explain 59.5% of the variance; the cognitive-motivational factor explained a large part of this variance with 47.21%, while the other two factors, negative state, and tiredness, together, explain only 12.32% of the variance. For this reason, the authors of the DISRS authors do not recommend the use of these factors as subscales; instead, the total summed score should be used.

The lowest communalities were found in items 18 and 19, which reached values of .365 and .345, respectively. Since construct validity was not significantly modified by eliminating these two items from the factor analysis, it was decided to keep them in the last version of the scale translated into Spanish.

Although the original factorial structure of the instrument was replicated, not all the items coincided in the conformation of the three factors defined by the authors of the scale, this is possibly explained by the variability of some items that make up the scale. The possibility of applying an abbreviated DISRS scale by removing the items from the negative affectivity factor should also be considered in future research (e.g., item 4 “Think about how unmotivated you feel,” item 8 “think about how sad you feel,” item 9 “think about how you don’t feel like doing anything,” and item 14 “think, I can’t get rid of this feeling”) because these items are similar to certain items of the depression subscale of the RRS. The nature of the construct needs to be better studied, in larger samples from general and clinical population, in order to generalize the results.

For convergent validity, questionnaires that evaluate constructs associated with rumination were used, such as the Ruminative Response Scale, the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ). Although these constructs show appropriate degrees of convergent validity, the highest correlation occurred between DISRS and RRS (r = .78) and PSWQ (r = .73). Evidence from previous studies has shown that depression, anxiety, and worries are chronic, aggravating factors of insomnia (Moberly & Watkins, 2008; Pearson, Watkins, Kuyken, & Mullan 2010), and that they also reduce the quality of life of those affected (Isaacs, Tehee, & Gray, 2021).

The most relevant correlation between the insomnia scale (ISI) and the DISRS factors occurred with the negative state (r = .72), followed by cognitive-motivational (r = .56) and tiredness (r = .49). There is some evidence on the use of rumination to relieve the emotional discomfort that the individuals suffer; however, it does not work in a lasting way, worsening the way of coping with problems because repetitive thoughts would focus on the causes and consequences of such difficulties and not so in the solutions (Hervás & Vázquez, 2006; Gruber, Eidelman, & Harvey 2008). Moreover, Du, Huang, An, and Xu (2018) found that higher level of rumination predicted higher degree of negative emotions experienced and vice versa. Additionally, rumination maintains physiological activation and emotional arousal in response to stressors. They may be the reason why daytime rumination can increase and maintain insomnia problems (Weiner et al. 2021).

Discriminant analysis enables subjects to be classified into two groups: participants with low and high levels of rumination associated with insomnia symptoms. Variable insomnia symptoms had a greater influence on the calculation of the discriminant function (SSC = .089) than worries (SCC = .033) and rumination unrelated to insomnia (SCC = .033). The discriminant function obtained helped classify 77 cases correctly, which corresponds to 75.5% of the total sample. Ten cases were false positives (19.6%) while 15 cases corresponded to false negatives (29.4%). Although the discriminant function is used to classify group membership, it is possible that not all independent variables are discriminant. Since the value of the Wilks’ Lambda statistic (λ = .611) denotes certain similarities between the groups, the influence of each of the variables on the discriminant function obtained must be studied.

Since this adaptation constitutes an initial approach to the study of ruminant thoughts and insomnia in Latin America, it would be advisable to follow up the subject to learn more about rumination in different age groups, in addition to finding out about the differences and similarities with the Anglo-Saxon population. In the clinical area, having a valid instrument and translated into Spanish that helps in the diagnosis and rumination clinical follow-up in insomniac individuals would make it easier for health personnel to determine the influence of ruminative thoughts on the effectiveness of pharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment. In addition, it will permit the identification of and intervention in people prone to rumination and insomnia to encourage them to seek more adaptive cognitive mechanisms that will help solve their problems rather than just frequently thinking about adversity, without acting or finding a solution (Takano, Iijima, & Tanno, 2012; Tousignant, Taylor, Suvak, & Fireman, 2019).

According to the cognitive model of insomnia, repetitive negative thoughts generate an emotional bias and selective attention, in which people exaggeratedly monitor the threat signals related to sleep, likewise the discomfort caused by difficulty sleeping gets worse thoughts and negative emotions, creating a cycle that perpetuates insomnia. (Harvey, 2002).

Rumination is a repetitive thinking process that limits the processing of external information to solve problems. In other words, a person with a propensity to think negatively tends to have greater difficulty integrating positive information that may distort their deeply ingrained negative beliefs (Lo, Ho, & Hollon, 2010; Carney et al., 2013). Our research suggests that insomniacs respond to daytime insomnia symptoms, repeatedly thinking about how much it bothers them to have unrestful sleep, this cognitive tendency is related to the severity of insomnia. A study carried out in pregnant women found that rumination exacerbates insomnia at night and that these repetitive thoughts would also be presents during the day and would focus on the consequences of not having slept well (Kalmbach, Cheng, & Drake, 2021).

Study limitations include the fact that the sample is unrepresentative, and therefore, the results cannot be generalized to the entire population studied. At the same time, the sample included mostly women, aged between 26 and 40, who live with their partners and have had more than nine years’ schooling. It is therefore necessary to determine whether the DISRS scale is also suitable for people with different demographic characteristics. Another limitation, it was not possible to rule out pre-existing pathologies in participants (e.g., depressive disorder, anxiety disorders), nor asking about the current use of medications. For future research, it is suggested to expand the clinical information by performing the physical examination, laboratory and other complementary tests. Finally, we have that the cross-sectional design of our research does not allow us to establish causal associations between variables.

The study concludes that the DISRS scale is valid and reliable for detecting ruminant thoughts related to daytime insomnia symptoms. Given that the DISRS was evaluated with other validated scales to establish convergent validity, future research could evaluate rumination associated with insomnia through other more objective diagnostic tests such as polygraphy and polysomnography. Finally, the authors suggest evaluating the psychometric properties of this tool in a clinical population with medical or psychiatric comorbidities.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)