No matter how happy you are in a close relationship, at certain moments conflict is inevitable (Canary, Cupach, & Messman, 1995).The strategies partners use (e.g., constructive and destructive) to resolve conflicts in close relationships is associated with their happiness (Fincham, Beach, & Davila, 2004); happier partners use constructive strategies more often. Despite the fact that this association between constructive (e.g., talking, listening), destructive conflict resolution (e.g., yelling, dominating the conversation), and happiness has been tested and supported previously, the extent to which it occurs among different ethnic groups needs further examination. In a previous study, we found that Turkish and Dutch as well as Turkish-Dutch immigrant couples used similar conflict resolution strategies (i.e., approach and withdrawal; Celenk & van de Vijver, 2013a).

In the present article, the main objective is to unravel the role of ethnicity in conflict resolution and its association with satisfaction in close relationships. Secondly, we aim at examining the role of acculturation orientations in these aspects among all major immigrant groups in the Netherlands. Acculturation orientations (i.e., cultural maintenance and adoption) among the immigrants are also believed to influence relationship satisfaction (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019a). We are interested in similarities and differences in destructive conflict resolution and relationship satisfaction among ethnic groups in the Netherlands. For the immigrant groups, the relations between conflict resolution, acculturation orientations, and satisfaction are also examined.

Destructive Conflict Resolution and Satisfaction in Close Relationships

Happiness in close relationships is important as it affects psychological and physical well-being of the partners (Hicks & Diamond, 2008). It has been argued that constructive conflict resolution is positively related to happiness, whereas destructive conflict resolution is negatively associated with happiness (Noller & Fitzpatrick, 1990).

Research from different perspectives on conflict resolution has identified several strategies to solve arguments. Rahim and Blum (1994) argued that a conflict can be resolved in five different ways: integrating, dominating, compromising, avoiding, and obliging (Rahim, 2002). Furthermore, destructive (e.g., physical, verbal aggression, criticizing, avoiding) and constructive (e.g., listening, compromising, integrating) strategies have often been named in the literature as possible ways couples use to manage their conflicts (Jensen-Campbell & Graziano, 2001; Noller & Fitzpatrick, 1990; Schneewind & Gerhard, 2002).

In the present study, our focus and definition of conflict resolution are based on the typologies of responses to dissatisfaction in couple relationships proposed by Rusbult, Zembrodt, and Gunn (1982). Constructive conflict strategies can be defined as “positive” ways couples use to solve the conflict and end the discussion. On the other hand, destructive strategies are more “negative” tactics used by couples which are considered as harmful because they have not the real intention of solving the conflict (Rusbult, Verette, Whitney, Slovik, & Lipkus, 1991). Rusbult and colleagues (1982) identified four typologies -voice, loyalty, exit and neglect- related to responses to dissatisfaction in couple relationships along the underlying dimensions of constructiveness and destructiveness. The former two have been considered as constructive ways with the main goal of maintaining the couple relationship by using various strategies, such as discussing the problems, talking with friends, focusing on solving the problem, waiting to solve the problem, and compromising. The latter two have been identified as destructive strategies without the real intention of repairing the relationship by avoiding, withdrawing, yelling, being physically aggressive, and leaving the room (for details, see Rusbult et al., 1982). It is important to note that the use of “constructive” and “destructive” is not based on couples’ consideration but rather on their effect on the relationship. For instance, a so-called destructive strategy (e.g., yelling at the partner) may be defined as positive, helpful, and constructive by the person who engages in the behavior; however, these kinds of behaviors have been found to be negatively related to satisfaction (Rusbult et al., 1991). Destructive conflict resolution is associated with more negative partner behavior than is constructive conflict resolution. We found evidence in a previous study for ethnic group differences in negative partner behavior in line with this argument. We found people with a non-Western immigration background displaying more negative partner behaviors than people with a Western immigration origin and mainstream Dutch background (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019b).

Despite the fact that constructive and destructive dimensions co-exist in a couple relationship, in the present study our focus is only on destructive strategies. The reason is the higher impact of the destructive dimension. It has been observed that there is 5:1 ratio of positive to negative behaviors in couple relationships; in other words, stable and happy relationships can only be achieved by displaying five times more positive than negative behaviors in the relationships (Gottman, 1993; Gottman & Levenson, 1992). Moreover, Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, and Vohs in their review emphasized the salience of “bad” over “good”; in other words, a key to happiness is exhibiting fewer bad behaviors than more good ones. Similarly, Rusbult, Johnson, and Morrow (1986) concluded that destructive behaviors predict distress more strongly than constructive behaviors.

The role of ethnicity. It has been argued that ethnicity has an effect on the way individuals deal with conflicts. For instance, Americans were found to be higher on the dominating style compared to Japanese and Koreans, whereas the latter two groups were higher on obliging and avoiding than Americans (Ting-Toomey et al., 1991). Furthermore, Cingoz-Ulu and Lalonde (2007) found Canadians to confront more in a conflict situation than Turks. These cultural/ethnic group differences can be understood in terms of differing culture value orientations.

Power distance and hierarchy may be used as a framework to understand these ethnic group differences. In Western cultures (supposedly more individualistic and affluent; Hofstede, 1991) interpersonal relationships are believed to be based more on equality. Similarly, couple relationships are more equalitarian and mutual, and individual autonomy is highly valued (MacDonald, Marshall, Gere, Shimotomai, & Lies, 2012). In non-Western cultures (presumed to be more collectivistic and less affluent; Hofstede, 1991), interpersonal relationships are shaped more by a larger power distance. Hierarchy has a bearing on couple relationships as males are generally more dominant and relationships are less equal (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019a). Regarding the destructive conflict resolution, previous research has shown that individuals in collectivistic cultures mostly avoid or withdraw in a conflict situation whereas individuals in individualistic cultures mostly confront or dominate while managing a conflict (Cingoz-Ulu & Lalonde, 2007; Holt & deVore, 2005; Ting-Toomey, 2005; Ting-Toomey et al., 1991). In a cross-cultural study, Thomas and Au (2002) found individuals from Hong Kong (higher on vertical collectivism; Triandis, 1995) to be higher on “neglect” and lower on “loyalty”, whereas individuals from New Zealand (higher on horizontal individualism; Triandis, 1995) are higher on “voice”. Strategies, such as avoiding, exiting, and neglecting, are preferred more by people in more collectivistic cultures to maintain peace and not to create any conflict in close relationships. People in more individualistic cultures are presumed to hold different strategies, such as dominating and voice, which can be considered as the emphasis on the autonomous self and individual gains and goals (Triandis, 1995).

We believe that strategies such as exit and neglect are the destructive replies by the submissive part in a hierarchical relationship (e.g., among females involved in couple relationships with male dominance). The part of the relationship that is higher in power is presumed to show a dominating/voice response (e.g., among males involved in couple relationships with male dominance). In other words, destructive conflict resolution is believed to be more likely among couples who are more dissimilar (unequal) in power.

Therefore, ethnic groups in the Netherlands including mainstream Dutch and individuals with different immigration backgrounds are believed to differ in destructive couple conflict resolution (e.g., neglecting, exiting, and being verbally and physically aggressive). Destructive conflict resolution is claimed to be preferred more by people who are supposedly involved in more hierarchical, male-dominated couple relationships. Destructive conflict management is negatively related to relationship satisfaction, which is believed to be less among dissimilar couples with larger power distance. Similarly, we found marital dissatisfaction to be higher among Turkish-Dutch immigrants than Dutch mainstreamers (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019a) and satisfaction to be higher among individuals with a Western immigration background compared to individuals with a non-Western immigration background (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2013b).

Immigration Background in the Netherlands

In the last century there have been three separate immigrant waves in the Netherlands, each time with different reasons. The first wave mainly involved former colonies of the country; Indonesian (around 1950s), Surinamese, Antillean, and Aruban (around 1965) people migrated to the Netherlands. The second wave was mostly due to employment; Southern European (around 1950s), Turkish, and Moroccan (around 1960s) individuals migrated to the Netherlands. The last wave mainly included political and religious refugees from former East Bloc countries (around 1970s) and Yugoslavia around 1980s (Schalk-Soekar, van de Vijver, & Hoogsteder, 2004). Since the 1980s, the main source of migration has been family reunification and formation (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2013b).

Individuals with Turkish, Moroccan, Surinamese, and Antillean/Aruban background are classified as having a non-Western immigration background. Individuals with an Indonesian background are classified as having a Western immigration background, because members of this group have lived in the Netherlands for a long time and have shown a strong pattern of assimilation (Statistics Netherlands, 2012). Figures of the Statistics Netherlands reveal that approximately 21% of the whole Dutch population has an immigration background. Turkish-Dutch group is the largest group with a non-Western immigration background, followed by individuals with Moroccan-Dutch, Surinamese-Dutch, Antillean-Dutch, and Aruban-Dutch backgrounds, respectively.

Individuals with Turkish and Moroccan background are more similar to each other and the same is true for individuals with Antillean and Surinamese background (van Oudenhoven, Prins, & Buunk, 1998). Furthermore, they perceive more distance from the mainstream Dutch individuals compared to individuals of Antillean and Surinamese background (Schalk-Soekar, van de Vijver, & Hoogsteder, 2004). Similarly, Turkish-Dutch couples were found to prefer cultural maintenance in couple relationships (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019a; for details of acculturation theory, see Celenk & van de Vijver, 2011).

The Present Study

The present study included six ethnic groups (mainstream Dutch and individuals with Turkish, Moroccan, Surinamese, Antillean, and Indonesian immigration backgrounds) living in the Netherlands. We examined three distinct aspects: (a) the association of ethnicity with destructive conflict resolution strategies and satisfaction among all groups; (b) the association of gender with these aspects and its interaction with ethnicity; (c) the role of acculturation orientations in relation to destructive conflict resolution and satisfaction among groups with an immigration background.

Regarding the first goal on the role of ethnicity, we hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1: Destructive conflict resolution is reported more by individuals with a Turkish, Moroccan, Antillean, and Surinamese background compared to individuals with an Indonesian background and mainstream Dutch.

Hypothesis 2: Relationship satisfaction is reported less by individuals with a Turkish, Moroccan, Antillean, and Surinamese background than by individuals with an Indonesian background and mainstream Dutch.

Regarding the second goal on the role of acculturation orientations, we hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 3: Destructive conflict is negatively associated with relationship satisfaction and cultural maintenance and adoption are positively related to relationship satisfaction in all groups with an immigration background.

Method

Sample

The present study included a total of 600 individuals living in the Netherlands. Respondents were members of the Tilburg Immigrant Panel1 that is based on a stratified random sample of immigrant groups in the Netherlands (including a random sample of the mainstream group). The Immigrant Panel is an independent part of the LISS panel of the MESS project (Measurement and Experimentation in the Social Sciences; for details of the panel, see Scherpenzeel & Das, 2010). Mainstream (non-immigrant) Dutch group had 391 individuals; there were 29 Turkish-Dutch and 29 Antillean-Dutch individuals, 34 Moroccan-Dutch, and 34 Surinamese-Dutch participants; 83 of the participants were Indonesian-Dutch. Details of the sample can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1 Sample Descriptive Statistics per Ethnic Group

| Background | Ethnic Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainstream Dutch | Turkish-Moroccan | Antillean-Surinamese | Indonesian | |||

| Mean age (years) | 50.03 | 37.05 | 45.40 | 51.31 | ||

| Femalesa | 49.11 | 52.38 | 52.38 | 48.19 | ||

| Mean monthly net family income (Euro) | 3244 | 1840 | 5669 | 4243 | ||

| Living with the partnera | 96.42 | 90.48 | 79.37 | 87.95 | ||

| Educationa | ||||||

| Primary School | 5.37 | 18.97 | 11.11 | 3.61 | ||

| Lower secondary education | 19.95 | 20.69 | 12.70 | 14.46 | ||

| Higher secondary education | 10.23 | 12.07 | 1.59 | 15.66 | ||

| Secondary vocational education | 25.83 | 31.03 | 30.16 | 19.28 | ||

| Higher vocational education | 24.81 | 13.79 | 30.16 | 24.10 | ||

| University education | 13.81 | 3.45 | 14.28 | 22.89 | ||

Note. a Percentage

As the sample size per group was not sufficient to make group comparisons and test the relationships across groups, we had to combine certain similar groups in line with the previous literature2. We combined people with a Turkish background and Moroccan background and people with Antillean and Surinamese background in order to reach adequate sample sizes (Schalk-Soekar, van de Vijver, & Hoogsteder, 2004).

Results revealed significant group differences for age (F(3, 596) = 23.08, p < .001, (partial) h2 = .10), net family income (F(3, 544) = 3.07, p < .05, (partial) h2 = .02), and education (χ2(15, N = 595) = 40.98, p < .001). Therefore, we controlled for the effect of age, net family income, and education in the analyses including all groups.

Instruments

Destructive conflict resolution. In order to assess destructive conflict resolution, we included four items (scale developed by the authors). Each item started with: After an argument: and continued as “I slam doors or yell”, “I leave it to my partner to solve the conflict”, “I continue the conflict without listening to my partner”, and “I hit, push, or slap occasionally”. Participants were asked to indicate their agreement on a 7-point Likert scale from completely disagree (1) to completely agree (7).

Relationship satisfaction. The scale to measure relationship satisfaction has already been used in previous studies and it was developed by Celenk and van de Vijver (2013b; adapted from the Satisfaction with Life Scale by Diener, Emmons, Larson, & Griffin, 1985). The measure included six items in order to examine the happiness of the participants in their close relationships. Items were “Overall, I am happy with relationship”, “In most ways, my relationship is close to ideal”, “I am happy with my nuclear family (children and partner)”, “I am happy with my relationship with my children”, “I am happy with my relationship with my spouse”, and “In most ways, my nuclear family (children and partner) is close to ideal. Each participant evaluated their happiness on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

Acculturation orientations. Acculturation preferences of the participants with an immigration background were assessed by a shorter version of a scale developed by the authors (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019a; adapted from Acculturation Orientations Scale, Galchenko & van de Vijver, 2007). This self-report scale was composed of 12 items to assess cultural maintenance and adoption. Each item started with: I find it important to: and for preference for cultural maintenance; six items continued as “Have close contact with families from my own ethnic group”, “Have family relationships as my own ethnic group does”, “Have a relationship with my partner as my own ethnic group does”, “Raise my children as my own ethnic group does”, “Watch my own ethnic group’s television channels”, “Speak language of my own ethnic group”. For preference for cultural adoption; they were “Have close contact with Dutch mainstream families”, “Have family relationships as Dutch mainstreamers do”, “Have a relationship with my partner as Dutch mainstreamers do”, “Raise my children as Dutch mainstreamers do”, “Watch Dutch television channels”, and “Speak Dutch”.

Procedure

Members of the Tilburg Immigrant Panel completed the questionnaires online by logging in to their panel accounts. All participants were either married (81.67%) or involved in a relationship longer than five years (18.33%). All the scales were developed in English and were translated to Dutch by using a committee approach. As panel members complete questionnaires on various topics each month; the time needed to complete a questionnaire is approximately 15 minutes per month.

Results

Psychometric Properties

Internal consistencies of the scales. Cronbach’s alpha values are presented in Table 2. As can be seen there, these values were mostly adequate (except for destructive conflict resolution in the Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian groups, which were just below the threshold value of .70; Cicchetti, 1994).

Table 2 Internal Consistencies per Ethnic Group

| Scale | Ethnic Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainstream Dutch | Turkish-Moroccan | Antillean-Surinamese | Indonesian | |||

| Destructive Conflict Resolution | .70 | .73 | .67 | .65 | ||

| Relationship Satisfaction | .92 | .95 | .92 | .90 | ||

| Cultural Maintenance | - | .81 | .82 | .89 | ||

| Cultural Adoption | - | .73 | .71 | .86 | ||

Missing Value Analysis. In order to replace the missing values in the data, we computed Missing Value analysis in SPSS19 separately for destructive conflict resolution, satisfaction, and acculturation orientations. Results revealed that the average of missing values for destructive conflict resolution was 7.75%, it was 6.57% for satisfaction, 14.47% for cultural adoption, and 18.08% for cultural maintenance. Results of the Little’s MCAR test were χ²(20) = 29.18, p > .05 for destructive conflict resolution, χ²(33) = 28.44, p > .05 for satisfaction, and χ²(252) = 308.96, p < .001 for acculturation orientations (only for groups with an immigration background). Results for acculturation orientations revealed that missing values were not completely at random. However, percentages of the missing values were not very high; therefore we replaced them and included the scales in the analyses. For all scales, the EM algorithm was used.

Invariance of the scales. We computed confirmatory factor analysis to test the equivalence of the construct (structural equivalence) as well as to identify whether they are on the same scale in each ethnic group (scalar equivalence; for details of the equivalence, see van de Vijver and Leung, 1997). Results are shown in Table 3. For the destructive conflict and satisfaction scales, measurement weights were invariant and the drop from weights to intercepts was not substantial, which supported both structural and scalar equivalence. However, this level of invariance could not be found for the acculturation orientations measures. The poor fit of the metric and scalar inequivalence probably resulted from the small sample size, as for the acculturation orientations, we could only include the groups with an immigration background; as a consequence, the data did not comply with the rule of thumb that for every estimated parameter (between 20 and 30 depending on the invariance model), there should be 10 observations. Therefore, we also computed a principal component analysis in SPSS19 to identify the factorial structure of the scales. Scree tests confirmed that all scales were unifactorial. For the acculturation orientations among people with an immigration background, the cultural maintenance factor explained 58.02% of the total variance and the cultural adoption factor explained 47.62%. All factor loadings were higher than .45, which is believed to be sufficient by common standards (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007).

Table 3 Measurement Invariance of the Scales: Measurement Weights and Intercept Invariance

| Scale | Invariance | χ²/df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | AIC | BCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Destructive Conflict | MW | 2.49** | .93 | .95 | .05 | 120.33 | 125.70 |

| Intercepts | 2.06** | .95 | .94 | .04 | 113.80 | 117.52 | |

| Satisfaction | MW | 5.91*** | .92 | .95 | .09 | 368.39 | 381.81 |

| Intercepts | 4.34*** | .94 | .95 | .08 | 349.52 | 359.44 | |

| Acculturation Orientations Cultural Maintenance | MW | 3.21*** | .85 | .88 | .10 | 204.47 | 215.17 |

| Intercepts | 3.37*** | .84 | .84 | .11 | 223.48 | 231.85 | |

| Acculturation Orientations Cultural Adoption | MW Intercepts |

3.26*** 3.52*** |

.78 .76 |

.85 .74 |

.11 .11 |

202.46 226.02 |

213.86 235.09 |

Note. TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index. CFI = Comparative Fit Index. RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation. AIC = Akaike Information Criterion. BCC = Browne-Cudeck Criterion. MW = Measurement Weights.

** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Then, in order to examine the equivalence of the acculturation orientations scales included in the present study, we computed Tucker’s phi values based on the factor loadings we obtained in Principal Component Analysis (values above .90 is considered as being structurally equivalent). All the Tucker’s phi values were higher than .90 across the groups, which support the structural equivalence all scales (van de Vijver & Leung, 1997).

Ethnic Group Similarities and Differences

To test the hypotheses on ethnic group similarities and differences and the interaction with gender, we computed separate multivariate analysis of covariance. Ethnic group (Mainstream Dutch vs. Turkish-Moroccan vs. Surinamese-Antillean vs. Indonesian) and gender (male vs. female) were the independent variables. We included four items of the destructive conflict resolution scale as well as the single construct, which was the average of the four items (first analysis), and six items of the satisfaction scale as well as the single satisfaction construct that was the average of the six items (second analysis) as the separate dependent variables. A single factor was extracted for age, education, and net family income and included as a covariate.

We found a significant multivariate main effect of ethnic group for destructive conflict resolution (four items and the average score as an approximation of the construct score), Wilks’ Lambda= .96, F(12, 1407) = 1.83, p <.05, (partial) h2 = .01. While focusing on the univariate effects, three items were significantly different across groups (or bordered on significance); leaving it to the partner to solve the argument, F(3, 535) = 2.54, p = .06, (partial) h2 = .01 (Turkish-Moroccan group scored higher than the mainstream Dutch group); continuing the argument without listening the spouse, F(3, 535) = 3.16, p < .05, (partial) h2 = .02 (Turkish-Moroccan group scored higher than mainstream Dutch and Antillean-Surinamese groups, respectively), and hitting, pushing, and slapping occasionally; F(3, 535) = 2.69, p < .05, (partial) h2 = .02 (Turkish-Moroccan group was higher than the mainstream Dutch). Only the item “slamming the doors and yelling” yielded nonsignificant results, F(3, 535) = .05, p > .05, (partial) h2 = .00, The univariate effect of destructive conflict as a single construct (average of the four items) was marginally different across groups; F(3, 535) = 2.54, p = .06, (partial) h2 = .01. Hypothesis 1 was partially supported as overall destructive conflict was significantly different across the groups; yet, the only difference was between the mainstream Dutch and Turkish-Moroccan immigrant groups as the latter being higher than the former (see Table 4).

Table 4 Estimated Marginal means per Subscale for Ethnic Group

| Ethnic group | Gender | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainstream Dutch | Turkish- Moroccan | Antillean- Surinamese | Indonesian | Males | Females | |

| Destructive Conflict Resolution | 2.23a | 2.61b | 2.16a,b | 2.27a,b | 2.19a | 2.45b |

| Slamming or yelling | 2.52 | 2.55 | 2.53 | 2.59 | 2.38a | 2.73b |

| Leaving to solve to the partner | 2.63a | 3.19b | 2.54a,b | 2.61a,b | 2.73 | 2.75 |

| Continuing without listening | 2.30a | 2.83b | 2.12a | 2.32a,b | 2.18a | 2.61b |

| Hitting, Pushing, Slapping | 1.48a | 1.88b | 1.45a,b | 1.54a,b | 1.47a | 1.71b |

| Relationship Satisfaction | 5.87 | 5.68 | 5.87 | 6.06 | 5.86 | 5.89 |

| Being happy with the relationship | 5.97a,b | 5.65a | 6.08a,b | 6.17b | 5.99 | 5.95 |

| Relationship close to ideal | 5.48 | 5.32 | 5.5 | 5.75 | 5.46 | 5.56 |

| Being happy with nuclear family | 6.08 | 5.81 | 6.1 | 6.21 | 6.05 | 6.05 |

| Being happy with relationship with children | 6.09 | 5.96 | 5.96 | 6.22 | 5.94a | 6.18b |

| Being happy with the relationship with partner | 5.97 | 5.73 | 6.02 | 6.18 | 5.97 | 5.97 |

| In most case. my nuclear family is close to ideal | 5.65 | 5.61 | 5.58 | 5.85 | 5.72 | 5.63 |

Note. Means with different subscripts are significantly different (Bonferroni adjustments were used for pairwise comparisons).

The multivariate main effect for satisfaction was nonsignificant (for six items and the average score as an approximation of the construct score) of the scale, Wilks’ Lambda= .96, F(18, 1500) = 1.20, p > .05, (partial) h2 = .01. All of the univariate effects were nonsignificant except “Overall, I am happy with my relationship”, F(3, 535) = 2.77, p < .05, (partial) h2 = .02. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was rejected (see Table 4).

The multivariate effect of gender on destructive conflict resolution was significant, Wilks’ Lambda = .98, F(4, 532) = 2.89, p <.05, (partial) h2 = .02 as well as all the univariate effects except leaving the argument to the partner, F(1, 535) = .01, p > .05, (partial) h2 = .00. Overall, females scored higher than males on all items. The multivariate effect of gender on satisfaction items was also significant, Wilks’ Lambda= .97, F(6, 530) = 3.08, p < .01, (partial) h2 = .03; there was only one significant univariate effect: being happy with the relationship with children, F(1, 535) = 4.68, p < .05, (partial) h2 = .01.

Regarding the interactions between ethnicity and gender the only significant univariate effect was “continuing the argument without listening to the spouse”, F(3, 535) = 2.85, p < .05, (partial) h2 = .02.

Relationships between Destructive Conflict Resolution, Acculturation Orientations, and Satisfaction (for Immigrant Groups)

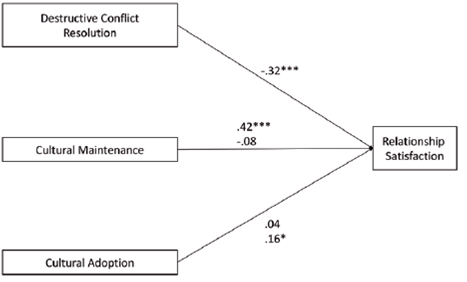

In order to examine the relationships between destructive conflict resolution, acculturation orientations, and satisfaction for participants with an immigration background, we computed a multigroup analysis in Amos (Arbuckle, 2009). We tested a model in which destructive conflict and acculturation orientations predicted satisfaction for all immigrant groups (See Figure 1).

Figure 1 Partial structural weights model with satisfaction as outcome for all immigrant groups. Standardized regression coefficients are given next to the arrows. Arrows with one number denote parameters that are identical for each group; arrows with two numbers present parameters for Turkish-Moroccan (the coefficient above) and the average of Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian groups (the coefficient below), respectively. * p < . 05. *** p < .001.

We first computed a structural weights model in which regression coefficients were identical across groups. The model had a poor fit (see Table 5). Based on an analysis of modification indices, we computed a partial structural weights model in which regression coefficients were identical for destructive conflict resolution across the groups; however, for the acculturation orientations coefficients were only invariant among Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian groups. Results of the partial structural weights model showed a good fit; χ²(4, N = 209) = 2.25, p> .05, χ²/df = .56, TLI = 1.19, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00 (see Table 5).

Table 5 Results of the Multigroups Analysis

| χ2/df | CFI | GFI | AGFI | TLI | RMSEA | Δχ2 | Δdf | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural weights | 2.43* | .79 | .97 | .84 | .37 | .08 | 14.58* | 6 |

| Partial structural weights | .56 | 1.00 | 1.00 | .96 | 1.19 | .00 | 2.25 | 4 |

| Structural covariancesa | 1.46 | .80 | .94 | .90 | .80 | .05 | 11.66 | 12 |

| Structural residualsa | 1.46 | .78 | .93 | .90 | .80 | .05 | 14.68 | 14 |

Note. a The structural covariances constraints the variance of the factors to be identical across groups, structural residuals refer to error residual variances related to the dependent factors. Most restrictive model with a good fit is printed in italics.

*p < .05.

In line with our expectation (Hypothesis 3), there was a significant negative relationship between destructive conflict resolution and satisfaction for all groups. However, for cultural maintenance and satisfaction the only significant and positive relationship was found for participants with Turkish-Moroccan background. For cultural adoption, significant positive relationships between satisfaction and adoption were only found for participants with Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian backgrounds, the groups that are more adjusted to the Dutch society. In sum, the salience of the effect of destructive conflict resolution on satisfaction was identical across the groups; however, the impact of cultural maintenance on satisfaction was more salient among the participants with Turkish-Moroccan background compared to the participants with Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian background. Nevertheless, the influence of cultural adoption on satisfaction was stronger for participants with Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian background than their participants in the Turkish-Moroccan group. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was partially confirmed.

Discussion

In the present study, we focused on three aspects in couple relationships. Firstly, we examined the relationships between destructive conflict resolution, acculturation orientations, and relationship satisfaction among individuals with an immigration background (i.e., Turkish, Moroccan, Antillean, Surinamese, and Indonesian) living in the Netherlands. Secondly, we addressed the extent to which destructive conflict resolution and satisfaction show similarities and differences across individuals with an immigration background and mainstream Dutch living in the Netherlands. Finally, we examined the extent to which ethnic group differences and similarities interact with gender differences and similarities among these groups.

Destructive Conflict Resolution, Acculturation Orientations, and Satisfaction Ethnic Group Similarities and Differences

Results of the study revealed that while controlling for age, education, and income, overall (multivariate effects) groups were different in destructive conflict resolution and similar in satisfaction. Destructive conflict resolution in couple relationships was assessed by focusing on exiting (e.g., leaving it to the partner to solve the conflict), neglecting (e.g., continuing the argument without listening to the partner), and being physically and verbally aggressive (e.g., slamming, yelling, hitting, pushing). While concentrating on each item and their average as a single construct (e.g., destructive conflict resolution and individual four items), we found that the similarity was related to an item which can be considered as the only item that does not involve the other party; the partner (i.e., slamming the doors and yelling). All the other items (i.e., leaving the argument to the partner, continuing without listening the partner, hitting, pushing the partner) included the involvement of the partner. Therefore, our study supports the idea that cultural value dimensions (individualism-collectivism, power distance) are more salient in understanding destructive conflict resolution strategies across ethnic groups when these strategies include both dyads and when the resolution is believed to be reached through the partner.

The main group differences were between mainstream Dutch and immigrants with Turkish and Moroccan origin. The only difference between the Turkish-Moroccan group and Antillean-Surinamese group was on “continue the argument without listening to the partner”, in which the former scored higher than the latter. Mainstream Dutch and people with Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian immigration backgrounds were similar in all items. These differences and similarities could be related to cultural distance of the ethnic groups to the Dutch mainstream group; the largest differences are mostly obtained for the groups that perceive the largest cultural distance to the ethnic Dutch group (e.g., Turkish-Dutch and Moroccan-Dutch). For instance, it has been argued that immigrants with a Turkish and Moroccan background perceive a larger distance to the ethnic Dutch than immigrants with Antillean and Surinamese backgrounds (Merz, Ozeke-Kocabas, Oort, & Schuengel, 2009). Furthermore, Turkish and Moroccan immigrants migrated for employment reasons whereas Antillean and Surinamese immigrants come from former colonies where encounters with the Dutch language and culture are common.

Similarities in relationship satisfaction are relatively in line with previous studies in which we did not find any differences among the ethnic groups in the Netherlands regarding relationship satisfaction (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019b). Firstly, our results indicated that group differences in destructive conflict resolution are not associated with similar group differences in satisfaction; ethnic group differences obtained in destructive conflict resolution (multivariate and fewer univariate differences) were not obtained in satisfaction. This suggests that individual and group differences in both constructs do not have the same meaning. There may be two explanations for this discrepancy. Kelley and Burgoon (1991) concluded that marital satisfaction is predicted by the inconsistency between expectation and perception (what you expect from your partner and how you perceive your partner’s behavior). It may well be that expectations vis-à-vis relationship satisfaction are lower in groups with more arranged marriages (the Turkish- and Moroccan-Dutch groups). Therefore, the point of reference (what does it mean to be high or low in marital satisfaction) may be different across groups. A second issue involves ceiling effects; participants in all groups had the tendency to score towards the extreme of the satisfaction scale (7 point), which may have reduced the power of the statistical analyses to identify group differences (for a discussion of acquiescence and other response styles across cultures, see He, van de Vijver, Dominguez-Espinosa, & Mui, 2014).

As an aside, it may be noted that more educated couples have more equalitarian relationships and that presumed cross-cultural differences in hierarchy largely reside in differences in educational levels. It could also be argued that our findings are contaminated by response styles. VanLear (1990) concluded that the relationships between sharing, satisfaction, and traditionalism might have been expanded by social desirability bias. After controlling for this bias, the differences on satisfaction disappeared among couples named as “independent” and “traditional”. In order to test the associations between social desirability bias and destructive conflict management and satisfaction, we obtained social desirability scores from a previous panel wave and computed correlation analyses. Results revealed significant positive correlations between social desirability and satisfaction and negative relationships between social desirability and destructive conflict resolution.

Gender Similarities and Differences

While concentrating on the differences and similarities between males and females on destructive conflict management, and satisfaction, the only difference between the sexes was on destructive conflict resolution; females reported using more destructive conflict resolution than males. Firstly, we recomputed the analysis on the item level and found that females indicated more “slamming the doors, yelling, hitting, pushing, continuing the argument without listening their partner”, whereas both males and females indicated similar levels of “leaving it to the partner to solve the argument”. Even though the items we used in the present study cannot be classified as assessing “demanding” or “withdrawing” patterns during conflict, our results are partially in line with previous research which has concluded that males withdraw and females demand more during conflict in couple relationships (Christensen, Eldridge, Catta-Preta, Lim, & Santagata, 2006). Although we did not find any differences on the withdrawing pattern “leaving the argument to the partner”, females’ higher scores on “being actively and aggressively involved in the argument” may be understood in terms of their “demand” to discuss and resolve the argument.

Apart from destructive conflict resolution, males and females reported similar levels of satisfaction (except happiness with the relationship with children). Hyde (2005), in her meta-analysis, concluded that males and females are more similar than different on most of the psychological variables (named as the gender similarities hypothesis). Likewise, in a previous study we found males and females to report similar levels of satisfaction in their couple relationships (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019b). In a study by Schulz, Cowan, Cowan, and Brennan (2004), males and females did not differ on “typical” marital behavior either.

Relationships among Individuals with an Immigration Background

In order to assess the associations between destructive conflict resolution, acculturation orientations (i.e., cultural maintenance and adoption), and relationship satisfaction among immigrant groups in the Netherlands, we computed a multigroup analysis. We found that groups are invariant regarding the effect of destructive conflict management on satisfaction. More specifically, destructive conflict resolution was negatively related to satisfaction in all groups. Previous studies have reported similar results (e.g., Papp, Kouros, & Cummings, 2009). In addition, we were interested in the role of cultural maintenance and cultural adoption in relationship satisfaction. Cultural maintenance was only salient for satisfaction among the Turkish-Moroccan group and it was unrelated among participants with Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian backgrounds. On the other hand, the salience of cultural adoption varied among the groups as well in the sense that cultural adoption was positively related to satisfaction but this relationship only existed among Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian groups. The salience of the relationships is quite in line with the acculturation literature. Firstly, in a previous study we found a similar pattern in the sense that acculturation preferences do not mirror each other (Berry, 1992; Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019a). Cultural maintenance has been found to be more important in relation to marriage-related dynamics compared to cultural adoption among Turkish-Dutch immigrant couples (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2019a). Our results take this finding a step further and supported the salience of cultural adoption among Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian immigrants. In other words, while there is a preference for maintaining the ethnic culture among the Turkish-Moroccan immigrant group and it more strongly relates to satisfaction among this group than Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesian immigrants, a different pattern occurs for the latter groups; cultural adoption is more important in relation to satisfaction than cultural maintenance among Antillean-Surinamese and Indonesians compared to Turkish-Moroccan immigrants.

Implications, Limitations, and Conclusion

Our study has limitations. Firstly, our study design included self-report data on couple relationships and acculturation preferences which are known to be subject to response bias (Paulhus, 1991). Secondly, panel members have limited time to complete the questionnaires. Therefore, each construct was measured by only a few items. We believe measuring destructive conflict resolution by including four items makes it difficult to generalize our findings, which may have caused the lower reliabilities for two ethnic groups; further studies should consider developing a longer scale of destructive conflict resolution. Our sample size per group (e.g., 29 individuals with Turkish and with Antillean origins) did not allow us to focus each group separately, instead we had to combine ethnic groups (i.e., Turkish and Moroccan, Antillean and Surinamese) to reach sufficient sample sizes, which questions the generalizability of the findings. Similarly, immigrant groups were too small to examine generation differences. In addition, ethnic groups differed on certain background variables and we controlled for these differences (i.e., age, education, and income). However, additional background variables (e.g., length of the relationship) might have an effect in our results which can be included in future studies. For instance, a recent study with Turkish couples observed a negative correlation between marital quality and relationship length (Cirhinlioglu, Özdikmenli-Demir, Kindap Tepe, & Cirhinlioglu, 2019). We suggest replicating our findings by focusing on the role of generational status as well as ethnicity.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our study has both theoretical and practical implications. More groups were studied than in earlier couple studies that addressed Moroccan and Turkish immigrants; the present research has taken into account all major immigrant groups in the Netherlands, which includes both immigrants with a Western and non-Western origin. Multiculturalism has been one of the leading topics among counseling researchers as well as practitioners and previous research has appreciated the sensitivity to and awareness of cross-cultural differences and similarities. Yet, most research was conducted in the United States and mainly focused on various groups living in the United States (e.g., Kinnier, Dixon, Barrett, & Moyer, 2008). We found that relationship satisfaction could be enhanced by emphasizing the reduction of destructive conflict resolution strategies to the extent possible. The mechanism seems to be applicable in various ethnic groups. Yet, the influence of cultural maintenance on satisfaction was more salient among immigrants with a Turkish and Moroccan backgrounds compared to individuals with Antillean, Surinamese, and Indonesian backgrounds. The general theme behind these findings seems to be that it is important to link to the dominant ethnic identity of the group, which could involve either the immigrant ethnicity or the mainstream ethnicity.

In conclusion, we believe our results will shed light on how to proceed and will give clues to policy makers as well as counselors in multicultural societies. The present study points out the core dimensions in destructive conflict resolution and satisfaction across different ethnic groups as well as the applicability (destructive conflict resolution to satisfaction) and the variance (in acculturation preferences) of these associations among groups with an immigration background living in the Netherlands. Indeed, this provides a valuable starting point for professionals working towards improving relation satisfaction of couples of different ethnic backgrounds.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)