A number of studies have shown that marital quality is lower for women than for men (e.g., Jackson, Miller, Oka, & Henry, 2014); however, not sufficient evidence has been gathered to conclude which variables are more detrimental to women marital satisfaction. Furthermore, research conducted with women of different origin suggested that culture is an important dimension in understanding their close relationships (Celenk & van de Vijver, 2013). Cross-cultural psychology provides crucial information about the similarities and differences of psychological processes in different countries and cultures. This perspective implies that some of these processes are common across countries (i.e. universalism) whereas others are culture-specific (Berry, Poortinga, Breugelmans, Chasiotis, & Sam, 2011). There is a need to carry out cross-cultural studies comparing countries so as to evaluate the impact of different norms and cultural values in relationships (Halford et al., 2018). Neglecting possible differences among women from different countries may lead to “Anglo-centric bias” (Wierzbicka, 1993); therefore, it is necessary to analyze cultural aspects that could unfold differences in their relational variables for a more comprehensive understanding of marital dynamics in women.

Attachment dimensions (Molero, Shaver, Fernández, Alonso-Arbiol, & Recio, 2016) and conflict resolution strategies (Litzinger & Gordon, 2005) may be mentioned among the most important variables explaining marital quality. These relational characteristics -enrooted intrapersonal attributes of the individuals but also shaped by interpersonal events- seem to heavily affect couple interactions; in fact, they are linked to aspects such as affect regulation, life satisfaction, subjective well-being, as well as to marital satisfaction (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). It has been suggested that differences in relational variables are due to socio-cultural and contextual characteristics (Archer, 2007; Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002; Triandis, 1995). Furthermore, cultural dimensions such as individualism-collectivism (IND-COL) and masculinity-femininity (MAS-FEM) have been associated with conflict style (Kaushal & Kwantes, 2006), communication (Lueken, 2005) and marital satisfaction (Burn & Ward, 2005). Nevertheless, the joint effect of aforementioned cultural dimensions and relational variables (i.e. attachment dimensions and conflict resolution strategies) on women’s marital satisfaction remains largely unexplored. Unfolding possible differences would provide relevant insight to practitioners who work with women from different cultures; generalizing culture-specific factors associated with marital satisfaction may be biased (Wang & Scalise, 2010) and potentially may lead to incorrect therapeutic strategies. In the next sections, we analyze the current state of affairs regarding the aforementioned individual and cultural variables.

Differences in Attachment across Cultures

Attachment orientations are patterns of the intense emotional bond that individuals develop with a few preferred others (Bowlby, 1969). In adulthood they are best described as two dimensions in the context of romantic relationships; attachment dimensions are patterns that activate and operate the attachment system, which are highly associated with a number of outcomes related to interpersonal relationships (for a review, see Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Attachment anxiety dimension is characterized by concerns about abandonment, whereas the attachment avoidance dimensions is characterized by discomfort with closeness and interdependence, and with a preference for self-reliance (Fournier, Brassard, & Shaver, 2011).

Cultural differences in attachment in infancy have been thoroughly examined (Mesman, van IJzendoorn, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2016): individualistic cultures have been found to socialize in autonomy and independence (Grossmann, Grossmann, Huber, & Wartner, 1981) leading children to developing avoidant relational styles more often. Research in cross-cultural differences in adult attachment is scarce, though (e.g., Agishtein & Brumbaugh, 2013; Wang & Mallinckrodt, 2006). Despite main features of attachment pointing to some universal patterns (e.g., van IJzendoorn, & Sagi-Schwartz, 2008), there is also evidence that culture is responsible for the expression of some differences in attachment dimensions (Del Giudice, 2011). Specifically, in the cross-cultural study carried out by Del Giudice with individuals from several regions of the world, he found a few differences: a compelling one revealed that North American women show higher scores in avoidant attachment as compared to East Asian women. As interesting as this finding is, the criterion for region grouping may appear somewhat vague so as to more precisely understand the underlying cultural variables accounting for those dissimilarities (e.g., Schmitt et al., 2003).

Shaver, Mikulincer, Alonso-Arbiol, and Lavy (2010) suggested that avoidant dimension is an adaptive function in more individualist cultures. Individualistic societies promote individuals’ personal autonomy and independence (Hofstede, 2001), while collectivistic ones reinforce the development of harmony, altruism and consideration of others (Quek & Knudson-Martin, 2006), as well as interdependence among people, groups and their needs as groups (Hofstede, 2001).This cultural aspect-i.e. individualism-has not been examined in cross-cultural studies composed by women (e.g., Schmitt et al., 2003). You and Malley-Morrison (2000) compared American and Korean college students’ attachment levels. By looking at their female sample, we may observe that American women, being a highly individualistic country, showed higher scores in avoidant dimension than Korean women, a country commonly referred as being collectivistic, following authors’ rationale. However, some other cultural dimensions accounting for such difference may apply (i.e. masculinity and femininity). Masculinity refers to societies where gender roles are clearly distinct for women and men (Hofstede, 2001). In contrast, in feminine cultures gender roles overlap (Hofstede, 2001) and they show a need for a more expressive relationship and concern about others (Zubieta, Fernández, Vergara, Martínez, & Candia, 1998). In addition, Alonso-Arbiol and colleagues (2010) found that in countries with greater distance between gender roles (i.e., masculine countries), individuals report higher avoidant attachment. Thus, we expect that women from individualistic countries will show higher scores in avoidant dimension as compared to those in collectivistic countries (Hypothesis 1) In testing this hypothesis, MAS-FEM dimension of the country should be controlled, though.

Cultural Dimensions and Conflict Resolution Strategies

Conflict resolution strategies reflect individuals’ tendencies to cope with marital problems. The possible different strategies displayed are classified either as negative (e.g., withdrawal and demand) or as positive (e.g., positive problem solving). Eldridge, Sevier, Jones, Atkins, and Christensen (2007) defined withdrawal as a strategy characterized by no confrontation of the problem (e.g., becoming silent), while demand strategy would imply aggressive behavior (e.g., criticizing and nagging); positive problem solving strategy would be characterized by behaviors that promote the satisfactory solution of the conflict (e.g., listening attentively and admitting own fault).

The relationship between IND-COL cultural dimension and conflict in general has been thoroughly analyzed, typically showing that more individualistic cultures tend to use more aggressive and dominating conflict styles while collectivistic cultures tend to use conflict reducing strategies and avoidant strategies (e.g., Forbes, Collinsworth, Zhao, Kohlman, & LeClaire, 2011; Kim & Coleman, 2015). Yet, the analysis at marital level and focused in women’s perspective has been understudied, and is well needed for the aforementioned reason of preventing from ecological validity bias.

Chinniah (2003) carried out a research study that analyzed exclusively women’s conflict resolution strategies from East Indian and European-American; she found that individualistic dimension (at individual-level) was associated positively with withdrawal strategy. This seems to be congruent with the conceptual similarity between withdrawal and individualism pointed out by Lin, Chew, and Wilkinson (2017). These authors argue that individualism stresses self-sufficiency, emotional distance and discomfort with closeness. Furthermore, Ridley, Wilhelm, and Surra (2001) stated that, apart from the evasive function (e.g., think of leaving the marriage), withdrawal strategy also taps the function of maintaining control over the relationship (e.g., stop argument early), which may be understood as a proactive strategy more likely to be displayed by women from individualistic countries. In other words, individualistic cultures would activate withdrawal as a self-sufficiency, agency, and independence strategy during the conflict. Chinniah’s (2003) study however, focuses on the individual level of individualism rather on the cultural dimension as defined by Hofstede (2001), which hitherto remains unexplored. Since individuals’ behaviors and affects across societies are partly determined by the macro level of culture (Erez & Gati, 2004), this analysis approach is especially relevant. Thus, we hypothesize that women from more individualist cultures will show higher scores in the perception of the withdrawal conflict resolution than women of collectivistic cultures (Hypothesis 2).

Regarding the demand conflict resolution strategy and linked cultural dimensions, as a first glance one may think of a proxy (i.e. aggression) for demand as related to individualism. Some authors pointed out to individualism as related to anger (Fernández et al., 2014) and that in individualistic cultures higher rates of aggression and violence are observed (Archer, 2007). However, when conflict in close relationships of individuals involved in a relationship is specifically analyzed, other dynamics should be taken into account. Aizpitarte (2014) examined dating violence in young individuals. She found that women in individualistic societies tend to report less emotional and cognitive aggression than collectivistic cultures. Individualistic women seem more likely to rely on their self-sufficiency; furthermore, they would not be that much concerned in effort and time investment in trying a strategy that may elicit, but not resolve, problems. Vandello and Cohen (2008) also looked at the close relationship and they linked societal collectivism (an index they developed with data from 46 preindustrial societies that consisted of obedience inculcation, negative self-reliance inculcation, degree of extended family structure, and use of arranged marriage) and Hofstede’s collectivism with other aggression forms, such as domestic violence. These authors argue that collectivistic priority would be to maintain family cohesion, even though this brings a high level of aggressiveness in marital relationships, probably from both genders. Therefore, we expect that women from more collectivistic cultures will score higher in their use of demand-type of conflict strategy than women from more individualistic cultures (Hypothesis 3).

The dimension of MAS-FEM has also been associated with communication styles and emotion expression (Lueken, 2005). Femininity as a cultural dimension is a characteristic associated with help behavior (Shea, Wong, Nguyen, & Baghdasarian, 2017), accommodation in the relationships (Kilpatrick, Bissonnette, & Rusbult, 2002), and effort to cope with the conflict and a lower presence of auto-destructive behavior (Tsirigotis, Gruszczynski, & Tsirigotis-Maniecka, 2014). Feminine societies stress the importance of relationships, and both husband and wife would focus on their relationship and its nourishment (Hofstede et al., 2010). When both members of the couple strive to nurture the relationship, one would expect that they would both commonly use positive problem solving strategies that promotes the positive resolution of the conflict and the respect for the partner. Thus, we suggest that women from feminine cultures would report using more positive problem solving strategies (Hypothesis 4a) and report that their partners are also more prone to use these strategies (Hypothesis 4b), as compared to women from masculine cultures.

Masculinity-Femininity and Marital Satisfaction

In addition to individual and relational variables explaining marital satisfaction, MAS-FEM may be an important cultural dimension exerting some effect on it (for a review, see Hofstede, 2001). By means of promoting equity in the relationship, feminine societies determine the perception of relationship and life quality and they underline sensitivity and the focus in the relationship (Hofstede et al., 2010).

However, Taniguchi and Kaufman (2014) found egalitarianism at individual-level was negatively associated with marital satisfaction in Japanese women. These results confirm the theory of expectation violation suggested by several authors (Kaufman & Taniguchi, 2009) that defines discordance between expectations and reality regarding various aspects of the marital relationship. Since they expect a more balanced contribution to the household and relationships general from their husbands, egalitarian women become more dissatisfied in their marriage. This issue has been observed in a masculine society (i.e. Japan), but may be amplified in a feminine society, where egalitarianism illusion may permeate society to a higher extent. Thus, women from more feminine cultures will score lower in marital satisfaction than women from more masculine cultures (Hypothesis 5).

The Current Study

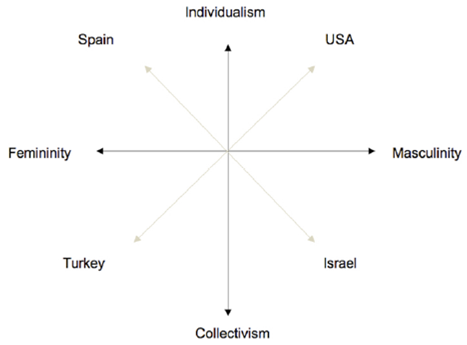

In this study we analyze relational variables of women from four countries which represent different combinations of IND-COL and MAS-FEM. As illustrated in Figure 1, USA is classified as a highly individualist culture, with a tendency toward masculinity (Hofstede, 2001). Turkey is considered a collectivist and feminine country, showing a great inclination to develop the equality, consensus and friendliness; avoiding the conflicts and giving importance to the consensus (Hofstede, 2001). Regarding Israel, Hofstede (2001) showed that it was a country with both individualist and collectivist characteristics. However, Triandis (1995) and Sagy, Orr and Bar-On (1999) classified it as collectivist society with a “great local patriotism”. Therefore, in the present study we followed these researches’ observation and considered it collectivistic. In terms of masculinity, although Israel is consider neither masculine nor feminine (Hofstede, 2001) when compared with Spain and Turkey, it would be closer to the masculinity end. For that reason, in the present study we have considered Israel as relatively masculine.

Method

Participants

The sample comprised of 343 women who reported being in a romantic relationship, of whom 25.1 % were from Israel, 14.3 % from USA, 13.4 % from Turkey, and 47.2 % from Spain. Their relationship lengths ranged from 0.17 to 47.2 years (M = 11.75, SD = 11.62). Their mean age was 35.4 years (SD = 11.83). Regarding marital status, 57.4 % of women were married, 31.5 % were cohabiting, and 11.1 % were just dating. Most women had one child (54.8 %). As for religion- in the Israeli sample, 47 % were Jewish and 48.3 % Christian. In the American sample, 43.5 % were Christian Catholic, 20 % Christian Protestant, and 28.2 % declared themselves having another religion. In the Turkish sample, 87.8 % were Muslim Shunni, and 6.1 % Muslim Shia, and in the Spanish sample, 61.1 % were Christian Catholic and 35.2 % atheistic.

Instruments

Sociodemographic data. Women completed a sheet with sociodemographic information. Collected variables were age, relationship status, relationship length, number of children and sexual orientation.

Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998; Spanish version by Alonso-Arbiol, Balluerka, & Shaver, 2007). The ECR is a widely used self-report questionnaire that contains two scales, each one with 18 items, for the assessment of attachment dimensions in the context of close relationships: Anxiety (e.g., ‘I worry about being abandoned’) and Avoidance (e.g., ‘I prefer not to show a partner how I feel deep down’). Higher scores of Anxiety show higher desire of excessive closeness with their partners; higher scores of Avoidance are indicative of a higher display of withdrawal and emotional distance. In this study, internal consistency reliabilities (Cronbach’s αs) of the Avoidant dimension scale were .88, .92, .85 and .87 for Israel, USA, Turkey and Spain, respectively, and values for Anxiety were .86, .87, .81 and .85 respectively for those countries.

Conflict Inventory (CI; Ridley et al., 2001). It consists of 16 items grouped into three styles: Positive, Withdrawal, and Conflict engagement. We used a revised version that also included descriptions of partners’ conflict resolution strategies. Participants indicated the frequency of use of these 16 strategies by themselves (CI-Self) and by their partners (CI-Partner), on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). The positive conflict resolution strategy emphasizes negotiation and compromising during conflict (e.g., focusing on the problem at hand). The withdrawal strategy includes refusing to discuss (e.g., remaining silent for long periods of time), and the conflict engagement strategy includes attacking, criticizing, and losing self-control (e.g., exploding and getting out of control). Cronbach’s alphas were acceptable for all the subscales of CI-Self (α = .70, .52, and .63 for Israel; α = .64, .64, and .58 for USA; α = .58, .73, and .89 for Turkey; and α = .51, .61, and .66 for Spain) and for CI-Partner (α = .79, .71, and .75 for Israel; α = .80, .73, and .74 for USA; α = .67, .59, and .66 for Turkey; and α = .67, .59, and .66 for Spain).

Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS; Hendrick, 1988; Spanish version by Molero et al., 2016). Participants answered seven items about the satisfaction level of their relationship (e.g. to what extent are you satisfied with your current relationship?) using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). In this study, internal consistency reliability was acceptable. Cronbach’s alphas for Israel, USA, Turkey, and Spain were .78, .81, .81, and .83, respectively.

Country-level information. The information about IND-COL and MAS-FEM cultural dimension were obtained from Hofstede’s study (2001).

Procedure

After institutional consent was obtained, collaborators from different countries participated in the adaptation of the questionnaires to the intended cultural groups, coupled individuals were contacted using snowball procedure in all countries and final version were administrated in each cultures. Each participant was informed and contacted individually and, after instructions for filling in the questionnaires were provided, s/he completed them and mail them back in a sealed envelope to ensure anonymity. Participation was on a volunteer basis; no remuneration was offered in exchange.

Analysis

Construct equivalence was analyzed by examining the similarity of the factors in each country; a separate analysis was conducted for each scale. Tucker’s phi coefficients were calculated for each country and each scale. This congruence coefficient measures factorial identity; values higher than .90 are usually taken as indication of similarities in underlying factors (van de Vijver & Leung, 1997). Tucker Phi coefficient values are shown in Table 1. The values indicate that attachment dimension, conflict resolution strategies and marital satisfaction were equivalent across the countries examined in the present study.

Results

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) were carried out to analyze differences across countries. Table 1 shows mean differences and standard deviation in each variable across countries. Differences across countries were observed in all variables except for marital satisfaction. (F (3, 339) = 0.56, p = 0.65).

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Tucker Phi Coefficient

| Israel | USA | Turkey | Spain | F | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M (SD) |

Tucker Phi |

M (SD) |

Tucker Phi |

M (SD) |

Tucker Phi |

M (SD) |

Tucker Phi |

||

| Attachment | |||||||||

| Avoidance | 2.96 (0.88)b | 0.99 | 2.11 (0.89)a | 0.99 | 3.57 (1.69)c | 0.95 | 2.17 (0.78)a | 1.00 | 32.50** |

| Anxiety | 3.26 (1.02)ab | 0.99 | 2.93 (0.98)a | 0.98 | 4.55 (1.58)c | 0.94 | 3.60 (0.78)b | 0.99 | 20.36** |

| Conflict Strategies | |||||||||

| Own Positive | 4.60 (1.02)b | 0.98 | 4.63 (0.91)abc | 0.99 | 4.56 (1.58)a | 0.98 | 4.67 (0.76)c | 0.94 | 4.33** |

| Own Demand | 2.12 (0.71)bc | 0.99 | 1.76 (0.48)ab | 0.98 | 4.13 (1.13)c | 1.00 | 1.81 (0.59)a | 0.99 | 5.55** |

| Own Withdrawal | 2.73 (0.77)b | 0.94 | 2.73 (0.79)b | 0.95 | 2.20 (1.45)a | 0.99 | 3.02 (0.81)ab | 0.98 | 4.86** |

| Partner Positive | 4.35 (1.24)a | 0.98 | 2.74 (0.92)ac | 0.97 | 3.61 (1.29)bcd | 0.99 | 4.02 (0.99)ad | 0.88 | 4.42** |

| Partner Demand | 1.83 (0.73)bc | 0.99 | 1.71 (0.71)ab | 0.98 | 2.26 (1.61)d | 1.00 | 1.69 (0.62)ac | 1.00 | 5.57** |

| Partner Withdrawal | 2.53 (0.99)a | 0.98 | 2.89 (1.58)ac | 0.92 | 3.61 (1.29)b | 0.97 | 2.86 (0.82)ac | 0.95 | 7.27** |

| Marital Satisfaction | 5.98 (0.78)a | 1.00 | 6.05 (0.79)a | 0.99 | 6.17 (2.08)a | 1.00 | 6.13 (0.72)a | 0.99 | 0.56 |

Note: Within each row countries that did not share a superscript differed from one another. *p < .05; **p < .01

Regarding attachment dimensions, avoidant attachment mean was higher in women from Turkey, followed by Israel, Spain, and USA. Hypothesis 1 was not supported because Turkey and Israel -collectivistic cultures- were expected to score lower in avoidant attachment dimension. Turkish women obtained the highest scores in anxious attachment, followed by Spain, Israel, and USA.

In Hypothesis 2 we expected that women from more individualistic cultures will show higher scores in the perception of the withdrawal conflict resolution than women of individualist cultures. This hypothesis was supported by the data. Spanish women had the highest scores in this conflict strategy followed by American women. As for the demanding conflict strategy, women from Turkey had the highest scores, followed by Israel, Spain, and USA. Hypothesis 3 was also supported because Turkey and Israel-collectivistic cultures-showed higher scores in this conflict strategy than the analyzed individualistic countries.

Regarding own and partner positive conflict resolution strategy, we hypothesized that more feminine cultures would perceive themselves and their partners as using more positive problem solving strategies (Hypothesis 4a and 4b). Hypothesis 4a was not supported since, although Spanish women-who live in a feminine culture-reported the highest scores in using this strategy, Turkish women had the lowest scores. Partners’ positive problem solving was reported mostly by Spanish women, but also by Israel women -living in a relatively masculine culture-. Thus, this hypothesis was not supported.

Finally, Hypothesis 5 suggested that women from more feminine cultures would score lower in marital satisfaction. There were not differences across countries in marital satisfaction; hence, this hypothesis was not supported.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyze differences in attachment, conflict resolution strategies and marital satisfaction among women of different countries. Our results suggest that there are differences across countries in attachment dimensions, as well as in conflict resolution strategies. However, we did not find differences in marital satisfaction of women from different countries.

Although previous studies have found a positive relationship between country-level individualism and avoidant attachment orientation (Frías, Shaver, & Díaz-Loving, 2014; Friedman et al., 2010), which has been explained as having an adaptive purpose (Shaver et al., 2010); our results of women’s attachment show an unexpected different pattern. Specifically, women from more collectivistic cultures scored higher in avoidant attachment. These results may be understood in light of other cultural elements which may have unique effects on women. For instance, Fuller, Edwards, Vorakitphokatorn, and Sermsri (2004) argued that in collectivist cultures where the extended family also satisfied individuals’ necessities, the partner may not be sought as source of emotional care. This may be applicable to women to a higher extent; women in collectivistic societies characterized by familism, are the connectors in the family network and use some other relatives more often for support and emotional guidance than their (male) partner. Future research in a larger number of collectivistic countries may look at this tentative explanation by assessing the joint effect with familism.

Although no specific hypothesis was formulated regarding the anxiety dimension of attachment, anxious attachment -reflecting a strong need and desire for closeness and intimacy (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016)- appeared in our study as being more characteristic of women of collectivistic cultures. The desire to seek greater closeness is consistent with the values and norms of more collectivistic cultures (Friedman et al., 2010). In the same line, Alonso-Arbiol and colleagues (2010) found that collectivism was positively associated with anxiety dimension in individuals (not gender was specified) from different countries. In female samples, some previous studies found Spanish women obtained higher scores of anxious attachment as compared to American counterparts (Alonso-Arbiol et al., 2008; Schmitt et al., 2003). Taking into consideration data from a micro-level perspective, although both countries having been described as individualistic, we may refer to Spain as being more collectivist country than USA. This issue, however, will necessitate a more in-depth study before unequivocal conclusions may be derived from the links between collectivism and anxious attachment in women.

Regarding cultural dimensions and the use of conflict resolution strategies, our hypothesis was supported; women from more individualistic cultures tend to use withdrawal during the conflict more often as a characteristic of their self-sufficiency and proactivity. However, some authors have obtained seemingly contradictory results in more unspecific settings. For instance, individuals from collectivist countries display a higher tendency to express emotions indirectly -i.e. silence- (Hofstede, 2001) to maintain harmony and positive relationships and, therefore, avoiding conflictive communicative processes (Matsumoto et al., 2008). Nevertheless, as mentioned in the introduction, one element of withdrawal in conflict resolutions involves an active strategy of withdrawal. In fact, a closer inspection of our data show that the item ‘stop discussion early’ is the one particularly and strongly associated with the distinction between individualism and collectivism, which indicates a more active (agency) strategy used by women from individualistic societies. Therefore, even though individuals from collectivistic societies tend to avoid conflict with outgroups in general settings, in close relationships individualism would be linked to the specific agentic facet of withdrawal strategy.

Regarding own perception about the use positive problem solving strategy and the perception of partners’ use of these strategies, our results did not confirm the hypothesized link of the cultural dimension MAS-FEM with the use of positive problem solving strategies. Hofstede’s labeling for masculinity/femininity certainly may capture role division equality; yet, some other features unrelated to it (i.e. achievement vs. preference for cooperation, heroism vs. modesty) are also included, which somehow lessen the possible link between the cultural dimension and problem solving strategy in the close relationship. It may be thought that country is not the only unit to examine cultural variability of conflict strategy, and in some countries a single rating for such dimension may be misleading. For example, a more fine-grained analysis in Israel showed that Jewish women tend to use demand themselves to a higher extent and to perceive that their spouses avoid the conflict to a higher extent as compared to Christian counterparts. Thus, future studies should examine countries but ethnic and/or religion may also be taken into account in the equation.

Regarding marital satisfaction there were not significant differences across countries. Our hypothesis that women from feminine countries (i.e. Turkey and Spain) would be less satisfied than women from masculinity countries, was not supported. This result is somehow congruent with Wong and Goodwin’s (2009) findings, who also acknowledged cultural similarities across three countries differing in MAS-FEM (i.e. United Kingdom, China-Hong Kong, and China-Beijing). Weisfeld and Weisfeld (2002) observed that in some cultures a decline in individual’s marital satisfaction may be more likely because the culturally appropriate behavior is to switch the focus from the spouse to caring for the children and the family in general, and therefore intimacy and partner’s needs are gradually neglected (Wong & Goodwin, 2009). In conclusion, differences in individual expectations about the relationship evolution would prevail over cultural elements on marital relationship.

To sum up, our results show relevant differences in relationship variables across cultures; yet, some limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, some Crobnach Alphas for Conflict Inventory subscales were suboptimal, as they were lower than the cutoff-point .70 value suggested by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) as rule of thumb. Apart from the above mentioned item of the Withdrawal subscale (#8: ‘stop discussion early’), an analysis of alpha values suggested deletion of item #1 (‘initiate the discussion’) from Positive problem solving and item #2 (‘blame my partner’) from Demand subscale for improvement of internal consistency. The 13 item version of the Conflict Inventory scale is recommended for future use with couples from Spain, Turkey, USA, and Israel. Secondly, only two countries per cultural dimension were included, which may limit somehow the impetus of the conclusions; further designs should include more countries as instances of each cultural dimension. Secondly, only two countries per cultural dimension were included, which may limit somehow the impetus of the conclusions; further designs should include more countries as instances of each cultural dimension. Thirdly, two pertinent cultural variables for the study of relational variables were examined, but some others that might have acted as confounding cultural variables (e.g., percentage of arranged marriages, women participating in leadership roles, ethnicity, religion, or violence acts) may have exerted an impact on observed results. Finally, in the present study, cultural impact has been exclusively analyzed from a country perspective and some relational variables may be better explained by a combination of country-level and individual-level characteristics (van de Vijver, Van Hemert, & Poortinga, 2014). Therefore, future research may be aimed at carrying out multi-level analyses combining the two levels in a larger sample and including a wider arrange of cultural dimensions.

To wrap up, our study highlights the importance of taking into account culture for the analyses of relational variables such as attachment and conflict. Differences among women from countries lead us to conclude that some cultural dimensions play a significant role in the expression of those relational variables essential for couple wellbeing and for solving marital conflicts. Based on this knowledge, clinicians and other practitioners may be better able to create and utilize culture-sensitive intervention strategies focusing on contexts that shape relational behavior.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)