What is history, what is it for? Its objective is not just the record of previous facts or events, placing them in a time line, but to give meaning to events, to understand the importance of those facts, to know how and why they occurred, and to analyze their influence in the future (Leahey, 1982). Nevertheless, it is important to note that the knowledge or interpretation of the past depends on the interests, sometimes opposing or conflicting ones, of groups of diverse nature (economic, political, etc.). As Leahey has pointed out, our view of the present is influenced by our knowledge of the past, and the opposite is also true. Thus, a rationalist culture will emphasize reasoning, as occurred, for instance, in some European countries, such as France or Germany, whereas an empiricist culture will emphasize experimentation, as took place in England and the United States of America. This phenomenon also ensues in the field of psychology. Each school of thought is linked to its time and culture; nevertheless, different academic or professional groups may coexist in historical and socio-economic contexts in any given place owing to specific interests (social demands, type of knowledge required to solve specific social problems, etc.) of those who promote a certain position or point of view.

The traditional ways of making history are represented by two extreme points of view: one may appeal to great personalities as forgers of history or one may appeal to impersonal forces. The first theory, or theory of the great man, was dominant mainly in the European Romantic era. The second theory, or theory of the Zeitgeist (from Zeit, meaning time and from Geist, meaning spirit: spirit of the time), was formulated by the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who asserted that the series of events that occur in a determined period of time are the result of impersonal forces that transcend individuals. The extreme form of this later perspective is religion, which contends for the existence of a predetermined destiny for each individual, or well, Marxism, which attributes the character of an era to the hegemonic economic forces of that time, whereas other forms of Zeitgeist are more limited, as the paradigms of scientific research. In this sense, the history of psychology is a history of ideas, rather than the history of events or biographies. In the history of psychology, it is well known that a given paradigm may disappear, or change, or be replaced by another one, whereas others paradigms may coexist as well. Thus, for the historian, it is necessary to analyze the intellectual Zeitgeist within the context in which paradigms and research programs operate. In order to accomplish this objective, and as Focault (1970) proposed decades ago, the concept of episteme, that is to say, the basic presuppositions that underlie all sciences in a specific era and which are generally unconscious and difficult to unravel, is fundamental.

Philosophy, Science, and Psychology

The history of psychology is, for the most part, the history of Greek philosophy. It seems daring to say it this way, especially when it is often said that the sciences, among them psychology, have been emancipated from philosophy. Even the most important models or paradigms nowadays, in one way or another, are related to this background. Therefore, it is necessary for the psychologist to know the history of the discipline, even superficially or in a partial way, and that is what will be briefly done below.

According to Larroyo (1947), the study of Greek history and philosophy allows us knowing our culture; Greek philosophical knowledge continues influencing our thinking and, of course, the psychology of our day. It should be noted that the geographical and political conditions of that time led to the great cultural, political, and economic development owing to the commercial and cultural exchange with people from other territories; the location of Greece in the eastern extremity of the Mediterranean Sea was a fundamental factor. Greece established maritime trade routes with Asia, receiving cultural influence from eastern countries; likewise, Greece took its cultural influence to Europe thorugh maritime routes. The various historical stages of Greek culture are omitted in this writing and it is only highlighted that Greek culture is considered the founder of science and philosophy, as Larroyo (1947, p. 129) has pointed out:

Hippocrates created medicine, and so did Euclid with geometry, Archimedes with mechanics. Eratosthenes with geography, and Hipparchus with astronomy. The greatest philosophical systems also arise from Greece: the conceptualism of Socrates, the materialism of Democritus, the idealism of Plato, and the most complete system of Greek sciences of Aristotle. Brief mention must be done of Greek religion, which was polytheistic and anthropomorphic; Greece recognized many gods who were represented under human forms and lived on Mount Olympus. This is important because of the historical religious implications that will later develop in the West, mainly with Christianity.

Greek Enlightenment and Psychology

The Sophists

For the aims of this study, it is necessary to date the emergence of psychology in the Classical Greece era (450-400 B.C.), mainly with the Sophists and Socrates. Owing to the profound political change in social relations as a consequence of the Greco-Persian wars, philosophy gradually integrated scientific ideas whereas other disciplines, such as medicine, gradually incorporated diverse theories and doctrines, giving rise, this way, to the relation between science and technology. One of the changes resulting from this historical process, and related to the Greek democracy, had implications in law, pedagogy, and psychology: the appearance of the sophists (sophós, meaning sage). Specialists in the economically rewarded and itinerant art of public discourse, the sophists created the formal laws of grammar and rhetoric; likewise, they fostered the development of logic, dialectics, and, important for the aims of this research, psychology because, in attempting to influence the will of their listeners, they had to be able to decipher and influence the emotional state of their listeners, thus initiating an anthropological period of philosophy that was characterized by placing man itself, besides the cosmos and the world, as an object of reflection.

The relativist philosophy of the Sophists, represented mainly by Protagoras, asserts that truth is relative. The criterion of truth varies in every moment and from man to man. The basis of this theory is the changing psychological situation of man. Protagoras, in fact, emphasized human subjectivity and, with this in mind, he was able to discover the psychological factor of education (Larroyo, 1947, p.150).

Socrates and Plato

In contrast to the Sophists, especially because of the economic retribution of education (since education should be an obligation of the State in order to guarantee the formation of the right kind of citizens that society wanted to have) and for the relativism and philosophical skepticism claimed by sophism, Socrates (469-339 B.C.) was convinced of the existence of a universally valid truth that could be reached through self-examination of oneself; his main principle was know thyself. The examination of concrete cases leads to the discovery of general concepts. The criterion of truth lies in a general anthropomorphism, that is to say, what seems to be true is true. Socrates' ideas are important in psychology insofar as they conceive the psychological and pedagogical phenomenon as a self-regulated activity (that is to say, it implies, epistemologically speaking, an active subject), and the different steps of his method allow us appreciating this. First, Socrates' method raises an issue of interest to an interlocutor. Second, the method requires the right answers from the interlocutor, although they might be wrong. This is the Socratic irony or interrogation. This second step, which leads to reflection or moral truth, consists of two parts, namely: the elenchus or refutation, which consists in exhibiting the ignorance of the interlocutor, and the maieutic (or giving rise to ideas) or heuristics (or discovering them). Through this method Socrates leads his/her interlocutor or disciple to find what is being looked for by himself/herself. Here we can glimpse the first conceptual bases of future dualistic or mentalist psychologies, including Piaget's and Chomsky's cognitive psychology and constructivist pedagogy.

Another one of the thinkers who would also strongly influence psychological thinking is Plato (429-347 B.C.). Plato grew up during the Peloponnesian War, leading to the decline of the political influence of Athens and its subsequent replacement by the political and military force of Sparta, which in turn modified to a great extent the conditions of life and the philosophical thought. Plato named the very principles of existence with the term “ideas” (hence the name of his system) and used the term “dialectics” to refer to the science that studied those “ideas” (Larroyo, 1947, p. 155). Plato, like Heraclitus, thought that reality was in perpetual change; the only perfect, immutable, and finished reality was the realm of ideas which could be accessed through education. It is through education that the ideas that fecundate the soul of man arise and make possible for the individual to live according to them. Plato, like Socrates, thought that ideas or knowledge do not come from outside the person. Thus, when knowing, indeed the individual recognizes or remembers what was already in his/her spirit through the dialectical method. Thus, when the soul resided in Hades (the world of ideas), the soul got to know the ideal world. Upon uniting with the body, the soul forgets that knowledge, and what it knows is just a mere reminiscence, being perception just the stimulus (as we would call it today) for that reminiscence. Misiak (1961, p. 37) wrote:

The soul is a prisoner of a body that obstructs and hinders it. Death separates body and soul, liberating the soul which, in turn, returns to the ideal world in order to live there eternally. The soul is a divine substance, intangible, immortal, and eternal; it can live independently of the body to which it had been united only accidentally and temporarily.

The preceding citation makes us suppose that Plato's philosophy had a great influence on Christian thought. This influence was prominent on the Late Church, and The Confessions of Saint Augustine (354-430 B.C.) allow us appreciating it. In St. Augustine's later philosophy, Hades is transformed into heaven and ideas become the soul that returns to heaven after the body dies.

Aristotle

About Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) it can be said that his philosophy is that of empiricism and development, always guiding himself in his inquiries by the order, the method, and the syllogistic logic that he invented (Leahey, 1982). Although he was a pupil of Plato for twenty years, Aristotle, unlike Plato, thought that what existed at first was the sensible world, whose objects give us sensations that gradually lead us to knowledge. In an epistemological sense, the cognoscente subject is reactive or adaptive to that preexisting reality.

Aristotle, who according to many thinkers is the true father of psychology owing to his emphasis on the senses as forms of adaptation and knowledge of the outside world, argued that the natural explanation of the world comprised four types of causes, specifically the final, the formal, the efficient, and the material; nevertheless, an entity like the soul can function as more than one type of cause simultaneously. The soul is the form (or formal cause) of a being and its actuality, and defines what kind of living being it is. The soul is the efficient cause of the movement of the body, and it is also its final cause because the body is subordinate to it. In this way, soul and body are inseparable, and although there is only one material reality (the body), it is composed of two aspects, which are the physiological aspect and the mental or rational aspect (represented by the human soul). In this way, Aristotle rejects Platonic dualism. Leahey (1982) clearly summarizes this historical polemic:

There are two important intellectual tensions that interweave over the later centuries. The first tension is found between rationalism and empiricism. The rationalist, starting with Parmenides, denies that the true knowledge comes from the perception and that is why the rationalist turns inwards, toward the reason and the innate ideas, in search for the truth. The empiricist, starting with Empedocles, looks toward the outside, believing that it is possible to lay the foundations of truth on sensory experience. The rationalist fears the illusions of the senses whereas the empiricist fears the deceptions of reason. The other tension is established between being and becoming. The supporter of the notion of being, often a rationalist, believes in eternal and transcendent truths and values that exist independently of the individual and that ought to be sought. The supporter of the notion of becoming, almost always an empiricist, denies the existence of the experience of eternal truths and immutable beings, finding in the changing flux of experience the only truth -that everything is in permanent change. The mutual interaction and struggle between these two intellectual tensions has been a constant source of motivation for intellectual life since the Classic Age.

Classic philosophy culminates with Aristotle. The Alexandrian Empire and the Roman Empire replaced the city-states, expanding civilization around the Mediterranean Sea, Europe, and Britain. There were not so many great philosophers and scientists at this stage of history owing to the pragmatic character of the empires. In any case, Plotinus (204-270) may be mentioned, who preferentially developed the mystical aspects of Platonism, converting them into a religion (as it would later happen).

Patristics and Scholastics

The dominion of the Roman Empire led, among other things, to the decline and fall of the Greek polytheism, and Christianity became the Roman state religion in the fourth century A.C. Christianity was not only a faith, but also a conception of life and man, as seen in the Epistles of St. Paul and the Gospel of St. John (Villalpando, 2004). The preaching of Christianity, and the conversion of those who heard the word of Christ, should be organized into a doctrine that would command and guide the Christian faith. At the same time, it was necessary to rationally ground it, protecting it from other pagan doctrines. This was the task of the fathers of the Church, who gave shape to the ideological movement called late Patristics, being St. Augustine (354-430) the most important representative. The way in which the formulation of this doctrine was carried out, taking as its starting point the philosophy of Plato, has been already seen.

On the other hand, Christian thought would recognize another attempt at dogmatic integration called scholasticism, or philosophy taught in school, whose purpose was the construction of a philosophy in which reason and faith could agree. In this philosophy, the Platonic-Augustinian roots of St. Bonaventure (1221-1274) and St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), representative of the Aristotelian tradition, were the most important.

The belief in the division of man into two irreducible substances (internal and external) is once again found, in the origins of Christianity, within the tradition of Judaism. Several authors have pointed out that the presence of what Ryle (1949) has called the ghost in the machine (Kantor, 1963, 1969; Ribes-Iñesta, 2004; Smith, 2007) can be traced back to Christianity. At the beginning, it was a spirit, mainly in biblical texts and in literary authors (for instance, Shakespeare [2007] in Hamlet); later on, and having Descartes in mind (1980), the term soul was retaken, which is the conception embraced, to a greater or lesser extent, by many thinkers in the West in order to explain human behavior. The mentioned authors have relied on texts written by the Late Church Fathers, all of them born after the first century AD, such as Justin Martyr (100-165?), Clement of Alexandria (150-215?), Gregory Thaumaturgus (205-265), Tertullian (160-240?), Hippolytus (170-236?), Athanasius (296-373?), Lactantius (260-330?), Gregory of Nyssa, (335-395), and Nemesius of Emesa (IV century AD); likewise, they have reviewed, historically and conceptually, works of Plotinus (204-270), St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430), St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), and Descartes (1596-1650).

More recently, René Descartes (1596-1650) and Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) formalized this dualist ideology in Western culture and, in this sense, the study of the Sacred Scriptures has been apparently overlooked, omitting the Evangelists as main sources. In this work, we have drawn upon writings of the beginning of Christianity, particularly upon writings of the Early Church Fathers as well as upon writings of the Evangelists Paul, Peter, and James related to this irreconcilable division, that is to say, the extraordinary coexistence of two completely different substances, namely: one of a material nature and another of a divine and immaterial nature. In the following lines, there are some excerpts from the New Testament that will be commented on in this context. It should be noted that St. Paul did not present a theological doctrine in his letters to the Corinthians, that he was rather responding to certain questions and intended to convince his/her interlocutors of the truth expressed in his arguments; these circumstances should be taken into account in order to properly interpret these texts (Heckel, 2000). In this sense, we should accept the cautious suggestion from Murphy-O'Connor (1991), who pointed out that the interlocutors to whom St. Paul addressed the Epistle II to the Corinthians were a mixture of individuals composed of both Judaizing Palestinians and Hellenic Jews.

In 2 Corinthians 4:16 it can be read: “…but though our outer man is getting feebler, our inner man is made new day by day”. Here it is very clear this premise of the simultaneous existence of two types of beings cohabiting in one entity: the first that welcomes the second one, or the second one that resides inside the first. The first, that represents the external cover of the second one, has a material nature and is suffering a constant death through corruptible deterioration. The second one is immaterial and has been made possible through the grace of God, who insufflated it into the first by means of the Holy Spirit and, since it has a divine origin, instead of dying, it is transformed successively and lives for all eternity. In 2 Corinthians 5:6 it can also be read: “…and though conscious that while we are in the body, we are away from the Lord…” This could mean that only when the body dies, then and only then could the second one be present, in heavenly terms, before God, which is immaterial. Also, in 2 Corinthians 5:10 it can be read: “For we all have to come before Christ to be judged; so that every one of us may get his reward for the things done in the body, good or bad.” According to this biblical text taken from the New Testament, Christ is the greatest or sole judge, not of bodily actions but of what the inner being, the true man, has commanded to the outer being to do for good or for evil, trying to ingratiate himself with God or, on the contrary, getting to offend God. What stands revealed here is the great problem of how an immaterial man (the inner being) can influence the material being (the outer being), since they are two completely different substances; in other words, what we have here is the classic problem of the imagined interaction between the immaterial substance and the material one.

In 1 Corinthians 6:19, it can be read: “Or do you not know that your body is a temple of the Holy Spirit who is in you, whom you have received from God, and that you are not your own?” It might be said that the inner man is the Holy Spirit, even though this would imply accepting that the Holy Spirit also commands the outer being to do bad deeds, which is not believable. But if the Holy Spirit is not the inner man, then, who is this mysterious inner man? Likewise, in 2 Peter 1:13-14 we can observe this clear difference between the material nature of the body and the immaterial nature of another being inhabiting inside the body until the death of the body, and the subsequent departure of the immaterial being towards an unfading and everlasting world: “I think it is right to refresh your memory as long as I live in the tent of this body, because I know that I will soon put it aside, as our Lord Jesus Christ has made clear to me”.

Finally, in James 2:26, it can be read: "As the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without deeds is dead". Here, we have again the dichotomous discourse between two antagonistic categories: what is corruptible and mortal, even in life, is the biological structure and function of the body, which, when actually dying, will then also lack the spirit, the eternal divine essence.

This study was carried out in order to find out how much relationship currently exists between this early Patristic ideology and the psychological belief systems known as mentalism and behaviorism, and the relationship of the latter with the cognitive, neuropsychological, and interbehavioral beliefs in psychology students who had just began to study their carrier.

Method

Participants

A convenience sample composed of 286 (84 men, 200 women and two participants who did not report their sex) out of 410 first-semester psychology students who were admitted at a School of Psychology of a public university located in Northeast Mexico was enrolled in this research. Mean age of the sample was 17.82 years (SD = 2.34; range: 16-38 years).

Instruments

A self-report instrument, composed of a socio-demographic questionnaire and a four-point, Likert-type scale, was administered to all participants. The scale (see appendix 2) was intended to assess the beliefs about interbehavioral psychology, cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, mentalism, behaviorism, and the ideology of the early Fathers of Christian Church. The labels for the scale were: Yes, I think so, I do not think so, and No.

Procedure

A postgraduate student administered the self-report instrument purposely created for this research to all participants in their classroom. The scale used to assess the psychological beliefs about interbehavioral psychology, cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, patristic ideology, mentalism, and behaviorism was created from both a questionnaire that was answered by specialists in the corresponding field of knowledge and from phrases extracted from specialized texts that addressed the different approaches of psychology that have been previously mentioned. The items composing this scale were designed by the authors taking as a basis the concepts expressed by the specialists that answered the questionnaire about the nature of cognition in psychology, all of them with more than 20 years of experience as teachers and researchers (see appendix 1).

After having got the approval from the University authorities to carry out the current research, having clearly explained the objectives of this research to the participants, and having obtained informed consent from the participants to be voluntarily enrolled in this research, the instrument previously described was collectively administered to the participants in their classrooms. A postgraduate student with wide experience in the administration of self-report scales administered the instrument to the participants, gave instructions to complete it, and stayed in the classroom during the administration of the instrument in order to clarify the doubts that might arise, trying not to influence the responses of the participants.

Data Analysis

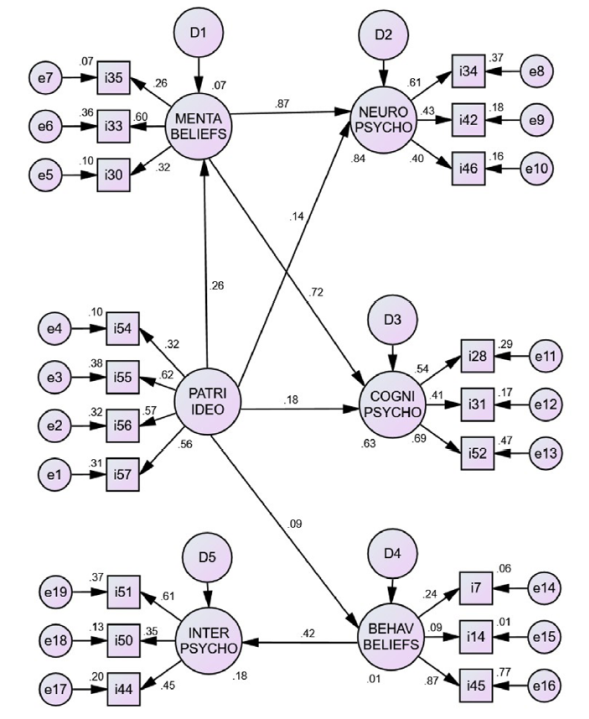

Structural equation modeling was used to explore the relationship between Patristic ideology and several current psychological schools of thought. The statistical calculation was executed by SPSS version 24 and AMOS version 24.

In order to assess if the proposed model showed a good data fit , the following goodness-of-fit indices were used: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < .06) (Hu & Bentler, 1999), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR ≤.08) (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999), Comparative Fit Index (CFI ≥.95), Incremental Fit Index (IFI >.95) (Hu & Bentler, 1999), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > .95), which compares the goodness of fit in relation with the degrees of freedom of the proposed model versus the degrees of freedom of the null model.

Results

The effect size (Cohen, 1988) of the differences between means of some psychological beliefs was calculated. It was found a very large size effect (d = 3.30; Hyde, 2005) between neuropsychological beliefs (M = 91.43) vs. Patristic ideology (M = 57.19) and a moderate effect size (d = 0.43) was also found between Patristic ideology (M = 57.19) vs. behaviorist beliefs (M = 63.23). The effect size that was found between mentalist ideology (M = 86.33) vs. Patristic ideology (M = 57.19) was also very large (d = 2.57), and it was also so (d = 2 .46) between cognitive beliefs (M = 86.19) vs. Patristic ideology (M = 57.19); likewise, there was a very large size effect (d = 1.24) between interbehaviorism beliefs (M = 73.86) vs. Patristic ideology (M = 57.19). Figure 1 summarizes the model that has been tested, which includes: 1) the relationships between the ideology of the Fathers of early Christian Church and mentalist, behaviorist, cognitive and neuropsychological beliefs, and 2) the relationships between mentalism and cognitive and neuropsychological beliefs, as well as the relationships between behaviorist and interbehaviorism beliefs. The model shows a good data fit: X²/df = 1.062; IFI = .981; TL = .976; CFI = .979; RMSEA = .015 (Carmines & McIver, 1981; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Figure 1. Standardized predicted model of neuropsychological, cognitive and interbehaviorism beliefs through mentalist and behaviorist beliefs as a function of Patristic ideology. The model was estimated using the method of Maximum Likelihood.

It can be seen, in Figure 1, that there is no direct statistically significant relationship between Patristic ideology and behaviorist beliefs (p = .387); the value of the β coefficient was .09 and the explained variance was 1%. Likewise, there is no direct statistically significant relationship between Patristic ideology and cognitive beliefs (β = .18, p = .111) nor between Patristic ideology and neuropsychological beliefs (β = .14, p = .270). Nevertheless, there exists a direct relationship between Patristic ideology and mentalist ideology (β = .26, p = .042), as well as an indirect relationship between Patristic ideology, mediated through the statistically significant effects of mentalistic beliefs, and both cognitive psychological beliefs (β = .72, p = .001) and neuropsychological beliefs (β = .87, p = .001), and the percentages of explained variance by each one of them are 63% and 84%, respectively. Finally, there is also a statistically significant relationship between behaviorist beliefs and interbehaviorism belief (β = .42, p = .014), and the percentage of explained variance is 18%.

Discussion

An explicit premise of this study is that, nowadays, psychology, in contrast to other disciplines such as physics and biology, lacks the ontological and epistemological support that could give it the status of science (Ribes, 2000), in spite of the fact that, in social sciences, there exist many scientific paradigms and that it is also possible to maintain a discussion in terms of programs (Lakatos, 1978) instead of paradigms (Kuhn, 2000). Thus, there seems to exist not just one but several psychologies with their own object of knowledge and method to study that object.

Among the current variants of psychological study, we can find a paradigm known as world-mind-body (Ribes, 2000), a paradigm that has been considered in this work as the paradigm of cognitive psychology. The paradigm brain-mind has been conceptualized here as the paradigm of the neuropsychological approach, whereas the paradigm mind-world would correspond to what, in this writing, has been called as mentalism. The paradigm reactive organism-world has been identified, in this research, as the paradigm of behaviorism. Nevertheless, it is possible that eventually a new paradigm will emerge that integrates some of the approaches of the diverse streams of psychological thought so that none of these streams could be disqualified in toto.

Findings in this study show that the early Patristic ideology (M = 75.28) is less accepted than mentalism (M = 86.33) by first-year psychology students. Perhaps early Patristic ideology, upon losing the social and political status as the dominant ideology that gave social cohesion to the Western world (Durkheim, 1982), was reborn in terms of Cartesian dualism, founded on the apotheosis of modern reason. Nevertheless, in spite of this decline of prestige, university students who have just begun studying psychology consider Patristic ideology (M = 75.28) to be more credible than behaviorism (M = 63.23). In other words, it seems to these students more coherent to believe that there are two incompatible substances coexisting in oneself than accepting only one of those two substances. It should be clarified that the belief that was measured here as behaviorism refers to what is known as Watsonian behaviorism, and no instrument was included for assessing the belief in Skinnerian behaviorism.

On the other hand, even though there is no direct relationship of Patristic ideology with cognitive and neuropsychological beliefs or with mentalism, the latter does relate directly and strongly to them. Perhaps, through the development of Western civilization, the transmutation of the ideology of the Fathers of the early Christian church was so successful (Carretero Pasín, 2007) that it is possible to see its effects, mediated through mentalism, on the most popular psychological beliefs. On the other hand, even though behaviorism is the least accepted belief (M = 63.23), it reappears with a better face and as a more appealing belief for first-year students in the form of interbehavioral psychology (M = 73.92), with which behaviorism shows a significant relationship, but far from the acceptance that these students show towards cognitive psychology (M = 86.18) and, above all, towards neuropsychology (M = 91.43).

Taking into account that the majority of the population of the state of Nuevo León, Mexico, declares to be Catholic and non-Catholic Christians (92.59%, 4,308,708 inhabitants out of a total of 4,653,458) (INEGI, 2010), this fact probably contributes to decrease the cultural permeation of the process of secularization in the professional formation of the future psychologists at a public university. The data yielded by this study point in the direction of a still strong influence of the Judeo-Christian thought in the thought of first-year psychology students and envision that, during their years of professional training, these students will identify more with the conceptual systems that have a deep intellectual root in mentalism and the ideology of the early Church Fathers, that is, cognitive psychology and neuropsychology. Nonetheless, this prediction will requiere to carry out future studies in order to explore the beliefs of psychology students in their last year of professional formation.

The limitations of this study include that the results obtained have a certain bias that affects its external validity. Another important variable that was not considered in the present study is related with the theoretical orientation of the academic program and, above all, the theoretical orientation of the teachers since teachers influence in a decisive way the belief systems of their students through supporting or disqualifying a certain point of view. Thus, for future studies, it would be desirable to explore the epistemological beliefs of the teachers and analyze how much influence they could exert on their students.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)