Introduction

Trade in slaves was outlawed in the British Empire in 1807. Slavery itself was prohibited in the British Empire in 1833. In Peru, the slave trade was outlawed in 1821. Slavery there was abolished in 1854. Despite this, and the fact that Britain never colonised Peru, British involvement in slavery in Peru and Bolivia continued into the twentieth century. It was particularly prevalent in the rubber producing areas of the Selva during the Amazonian “Rubber Boom” of the early twentieth century.

The Putumayo Atrocities are well known. While descending the Putumayo River, W. E. Hardenburg, a U.S. railway engineer, was captured and detained by agents of the British registered Peruvian Amazon Company. He escaped and revealed the most appalling practices including murder, torture, mutilation, castration, rape (including girls as young as seven), immolation with kerosene, robbery and human trafficking. Hardenburg wrote, “The region monopolised by this company is a living hell -a place where unbridled cruelty and its twin- brother, lust, run riot, with consequences too horrible to put down in writing. It is a blot on civilisation; and the reek of its abominations mounts to heaven in fumes of shame”. C. Reginald Enock described the company’s methods as “perhaps the most terrible page in the whole history of commercialism… the scene of the ruination and wholesale torture and murder of tribes of its defenceless and industrious inhabitants”.1

In Britain, the magazine Truth, the Anti-Slavery Society and the London Times newspaper publicised Hardenburg’s revelations.2 The British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, appointed diplomat Sir Roger Casement to conduct an enquiry. Casement’s reports were published in July 1912.3 He revealed “a systemised barbarity not equalled by King Leopold’s regime in the Congo”. He found that the Arana brothers, who directed operations, exterminated the existing settlers and then enslaved “the whole native population… by intimidation and brutality on a scale and of a kind which forbid description. Flogging by means of thick leather thongs, which often ended in the death of the victim, was literally the least appalling of their methods. There was no question of payment for the rubber brought in. Either it weighed the required amount or the penalty was extracted”. Sometimes, victims were pegged-out on the ground. At other times, they were flogged in stocks. Rubber “pirates” were “shot at sight”. Private rubber wars recalled “the feudal conflicts of the early Middle Ages”.

The British directors of the company denied any knowledge of the atrocities. In Parliament, the Prime Minister, Lord Asquith, referred to “the exceptional circumstances” of the Putumayo allegations. Francis Dyke Acland, Under- Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, gave an assurance that, “No outrages of any kind were committed by Englishmen”.4 Enock wrote,

The local conditions which rendered possible the Putumayo atrocities are to be found, first, in the character of the Iberian and Iberian-descended peoples of South America, and, second, in the topographical formation of the country… Apart from topographical considerations, the sinister occurrences on the Putumayo are, to some extent, the result of a sinister human element - the Spanish and Portuguese character.5

These opinions were disputed by British explorer Colonel Percy Fawcett. He wrote to The Times suggesting that the rubber industry in “the whole of forest Peru” should be investigated. It was “obviously improbable that such scandals are confined to one of the better known and relatively more accessible affluents of the Amazon. Other tribes are held up to slavery besides those of the Putumayo”.6 Fawcett’s view was that “real slavery was the rule (though covered by quasi-legal formalities)”.7

Were the Putumayo atrocities exceptional? To what extent was British capital involved in the exploitation of indigenous people to produce rubber? The “Rubber Boom” was one of the most important phases in the recent history of the Amazon Basin. There is significant literature about rubber extraction by European and North American companies in Brazil and Colombia; the Putumayo atrocities are well documented; Fifer has described in broad terms the activities of the Bolivian House of Suarez;8 and Brass and Bedoya have written about bonded labour;9 but there has been little in-depth analysis of the methods and financing of rubber extraction in the Peruvian and Bolivian Selva. Using primary, contemporary records, including the diaries of Fawcett and his colleagues Costin and Murray, the Reports of the Peru-Bolivia Boundary Commission 1911-1913 and company records, this article explores the operations of one British company, the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate, with particular reference to the treatment of indigenous people; the involvement of British capital and management; and the extent to which its treatment of its workers amounted to slavery.

Slavery in Peruvian Rubber Collection

Asquith’s statement that the Putumayo atrocities were exceptional was disingenuous. Lucien J. Jerome, the British consul in Callao (Lima’s port), had “written endless despatches about the treatment of Natives by Rubber companies” to the Foreign Office, but these were not made public. He wrote that although “the Peruvian Amazon is the worst, it is not by any means the only one”. He mentioned two other London companies, the Imambari Rubber Co Ltd and the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate Ltd, and two U.S. companies, the Inca Rubber Co and the Boston Rubber Company.10 The treatment of indigenous people on the Madre de Dios was “slavery pure and simple”.11 He believed that there was a “regular slave market” on the Madre de Dios and made frequent references to correrias (slave raids to capture indigenous people).12 Two monks, who were members of a Papal delegation to Peru, told him that conditions in the interior were “beyond the power of description”.13

The Tambopata Rubber Syndicate Limited

In part, Fawcett’s observations were based on time he spent in the region of the Heath and Tambopata rivers between 1910 and 1912.14 He had been contracted by the British Royal Geographical Society to survey and delineate the boundary between Peru and Bolivia. During those expeditions, he stayed at San Carlos and Marte, two rubber barracas (collection stations) owned by a British registered company, the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate. His small party included Doctor James Murray,15 a Scottish biologist, who had accompanied Ernest Shackleton on his 1908 expedition to the Antarctic, and Corporal Henry Costin, a former army gymnastic instructor.16

The Tambopata Rubber Syndicate Limited was registered in London in 1907. Its objects were

To purchase, acquire and take over (1) two rubber growing estates to the east of the Tambopata River, one known as “El Porvenir” and the other known as “La Union”, held under the Bolivian Government at a yearly rent of one Bolivian dollar per Estrada…;17 (2) the benefit of a concession granted to Don Carlos Franck by the Bolivian Government under which he is entitled to certain rubber ground for each league of road built under such concession.18

By an agreement dated 1 July 1907, between Franck, the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate and Antony Gibbs and Son, Franck sold his interests to the Syndicate for £10,000 in cash and shares in the company. There were 15,000 £1 shares; 7499 held by Franck; 7501 held by Antony Gibbs and Son.19 The capital for the purchase was provided by Gibbs.

Antony Gibbs and Son were an English trading partnership, set up in 1802. They had been the principal supplier of Peruvian guano to Great Britain in the nineteenth century but then developed major interests in South American wool.20 They expanded into shipping, the import of other raw materials and the export of European manufactured goods. By the turn of the century, they were also establishing themselves as a merchant bank. Franck had already been using Gibbs to sell rubber and in return ordering European goods.

The rubber collection was to be supervised by William Ricketts and Son of Arequipa. William Ricketts was born in Stourbridge, Worcestershire, the son of a Wesleyan Minister. He emigrated to Arequipa in the 1860s, initially to work for another English merchant house, Stafford and Co. He set up his own business in 1895, principally exporting wool to England and importing manufactured goods. Gibbs shipped and sold the wool Ricketts exported from Peru and, like Franck, Ricketts commissioned them to buy and ship out European goods. Franck, Ricketts and Tambopata Rubber all had credit accounts with Gibbs. 21

In September 1907, Tambopata Rubber mortgaged its “estates, farms, works, buildings and concessions” to J. A. Gibbs and B. I. Cockayne (partners in Antony Gibbs and Son) as security for £15,000 loaned to the company. That mortgage was registered with the Board of Trade, meaning that, as sole debenture holders, the whole of the company’s property was in the “hands” of Gibbs.22 They ran the British side of the operation. In June 1908, Tambopata Rubber formally appointed them as its commercial agents for a period of ten years. Gibbs were to ship and sell all the company’s rubber with a commission of 3%. They agreed to give the company and its agents letters of credit allowing them to draw against the rubber shipped. Gibbs were to purchase and ship out machinery and other merchandise required by Tambopata Rubber. For that service, the company paid a commission of 2½%. Gibbs also agreed to provide offices, a secretary and staff.

William Ricketts and Sons supervised the Peruvian side from Arequipa. This structure, especially the multi-faceted role of Gibbs, was typical of the way in which British, and other European merchants, had traded for centuries; allowing profit to be made both on the import of raw materials and on the export of manufactured goods.23

San Carlos and Marte

In 1910, the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate’s concessions comprised 349,620 hectares.24 They were in a region of natural, sub-tropical rain forest where rubber trees grew wild. It was “densely forested, clothed deeply with the debris of past generations of rotting vegetation, pathless, except for the rubber tracks, reeking with mist and moisture, and alive with pestiferous insects”.25 “To cut a way through the forest, a machete… must be used at every step”.26

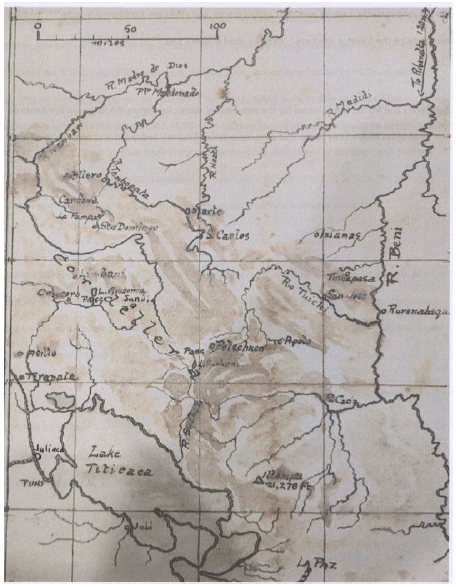

San Carlos and Marte, the barracas for the two estates, were clearings in the jungle on the banks of the Tambopata River. They comprised almacenes (store houses), bedrooms and open halls, all built of local materials. The walls were made of narrow strips of wood, slightly curved in section like barrel staves. They were tied in cross pieces by strips of tough bark.27 Roofs were palm thatch. They were not sturdily built. One afternoon, at San Carlos, “a terrific squall blew in the wall, took off some of the roof and soaked everything”.28 They were remote (Figure 1).29 San Carlos was between 38 and 40 leagues (c190 kilometres) from Santa Cruz in Bolivia; a five-and-a-half day journey by mule.30 It was 377 kilometres from the Peruvian railhead at Juliaca on the Altiplano. Access was largely by mule tracks, via Cojata, Pelechuco, San Juan de Tambopata and Paujilplaya, where travellers crossed the Tambopata by balsa raft, and then a further 32 kilometres to San Carlos along another mule track constructed by the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate.31 Conditions varied according to the weather. In October 1911, Major Toppin, a boundary surveyor, described the track as a “carefully laid out road with gradients up which mules can travel easily”.32 In August 1911, Fawcett found it potholed, with deep mud.33 The Boundary Commission Surveyors estimated that it took fifteen days to travel from Juliaca to San Carlos by mule.34 Marte was 48 kilometres beyond San Carlos, a journey of another two to three days. Marte was not accessible by mule.35 Everything had to be man-handled in and out of Marte.

Local Indigenous People

The region was very sparsely populated. Unlike the Altiplano, where there had been contact between Europeans and indigenous people for centuries, it had been little visited by Europeans.36 In 1899, when the Bolivian government granted the initial concessions to extract rubber in the Tambopata region, the lands were “inhabited by savages” and owned by the government. Franck was the only commercial operator nearby.37 The Syndicate claimed that their manager was “the only white man for many leagues” and that the “local Indians” were “of a war-like nature”.38 The Selva was still a frontier region where the relationship between Europeans and the indigenous population was a continuation of the Spanish conquest.39 Valentine Ashton, an English empleado at San Carlos, described the “savages” as “half-tamed and almost harmless, except for their clever stealings”.40 Fawcett referred to two ethnic groups. The Echocas (or Echojas) were a small tribe living in the valleys of the Tambopata and Heath Rivers. They tended chacras, fields of manioc, maize, vegetables and fruit, such as bananas. They fished and hunted and lived in large communal huts.41 According to Fawcett, they were “peaceable”, “kindly” and “friendly”. Toppin described them as “semi-civilised… a low-bred, mixed type”.42

Fawcett described the second group, Huarayos (or Guarayos), as wearing bark shirts or long gowns, with faces painted in square patterns with the juice of the urucu berry. They were armed with shot guns obtained from picadores (rubber choppers) or bows and arrows. They caught fish by stunning them with soliman sap.43

Fawcett was wrong in identifying Huarayos and Echocas as separate groups. Ese Eja (or Echoca, as Fawcett pronounced it) means “people” in the Huarayo language.44

British Staff at San Carlos

Tambopata Rubber’s manager of the San Carlos barraca was an Englishman, Arthur Cecil Lawrence. He was born in 1877 in Shenfield, Essex, the son of Henry Lawrence, a veterinary surgeon.45 He travelled out to South America some time before 1901 and worked in the rubber industry in the Beni Valley in Bolivia.46 He was the administrator of rubber baron Nicolás Suárez’s barraca at Costa Rica on the Rio Tahuamanu and fought for Bolivia against Brazil during the Acre War.47 He styled himself “Don Arturo”.48 He first travelled from Arequipa to San Carlos in September 1907.49 On 18 September 1908, he was baptised into the Catholic Church as Arturo Lawrence in Arequipa Cathedral, with William Ricketts’s son, Luis, as his padrino (godfather). Two days later, he married a Bolivian woman, Maria Mercedes Terrazas Otero.50

Gibbs thought that Lawrence “managed the business very capably”. He was “thoroughly versed in the management of Bolivian workmen”.51 However, Jerome, the British consul in Callao, had heard “bad reports” of Lawrence.52 Fawcett and his companions were highly critical of him. Lawrence welcomed them “hospitably”53 at San Carlos, but Costin wrote

On arrival we found the manager was not a typical Englishman; I can visualize him now as a sort of half brother to Goerïng; fat, vain, lazy! When he bathed in the river, two Indians went with him, to strew palm leaves on the ground where he sat, and one took off and put on his clothes; the other dried him.54

Murray wrote, “He is far advanced in evil and possesses a rich vocabulary. Lawrence keeps an Indian woman here, while he has a wife in La Paz”.55 Franck was also critical of him, writing that he used “to cause and provoke bad feelings between other people, wherever he finds a chance to do so, and sometimes he plays dangerous games”.56

The only other Englishman at San Carlos was Valentine Ashton, who worked in a more junior role. Murray described him simply as “a tall young English empleado”.57 Ashton was born in 1886, the son of John Ashton, a greengrocer and publican, in Lower Broughton, Salford. He left Liverpool for Arequipa in 1908. His role at San Carlos is unclear. Although he had no formal accountancy training, one of his daughters described him as, “part accountant, part general dog's body”.58 It may be that he was an accounting clerk.

Local workers

Tambopata Rubber relied upon a large number of indigenous workers, but Lawrence frequently complained that he could not secure enough labour.59 Estimates as to the number working varied. Costin referred to the Syndicate “employing up to 500 picadores”.60 Toppin wrote that the company employed 400 men working in the forest.61 Fawcett and Murray referred to the need to feed three hundred men at Marte in 1911.62

Many workers came from the Altiplano. In 1909, Lawrence “obtained” 250 men at different fairs.63 In 1911, Murray passed forty-eight new picadores on the track down to San Carlos. The Boundary Commission surveyors took photographs of “long haired Aymara porters at San Carlos”.64

The company records for 1909-1910 listed workers coming from Santa Cruz (92), Mocomoco (84), Ítalaque (37), Pata (16), Ayata (16), La Paz (9), Aten (8), Chuma (6) (all in Bolivia), (6), Apolo (31), Tambopata (18), Cojata (11), Sina (12), Vilque (11), Pelechuco (8), Putina (8), Pauji Playa (7), Sandia (7), and Quiaca (5). In addition, local Ese Eja were pressed into service.65 Most were picadores, but there were also fifty men to work on road building and fourteen empleados (including foremen, book keepers, guards, cooks and “house boys”), nine contractors, 23 fleteros (hauliers or carriers) and some other daily workers.66

In 1911, the average daily wage of a peon in San Carlos was 1.35 bolivianos, ranging from 0.60 bolivianos to 2.00 bolivianos. The rate of pay for caucheros depended on the quantity of rubber that they harvested. Lawrence received an annual salary of £1,200 sterling.67

Enganche por deudas

The enganche por deudas (literally “hooking by debts”) system was prevalent throughout Peru.68 It was bonded labour, often forced. Employers advanced money or some other benefit (transport, accommodation and/or food) which became a debt which the worker had to pay off by his labour. It was common for workers to be forced or tricked into this financial arrangement, without fully understanding it. Illiterate peones found themselves bound by written contacts which they had signed, but not understood. The necessaries provided in return for their employment (food, accommodation) were normally overpriced. Debts tended to increase not reduce. Under Peruvian law, a worker was legally obliged to stay with his employer until the debt was paid off. Often that was impossible. (The equivalent “truck” practices which were prevalent in eighteenth century Britain were outlawed by the 1831 Truck Act and the 1887 Truck Amendment Act.).

The Tambopata Rubber Syndicate continued to operate the enganche system used by Franck. When Franck sold the estates to Tambopata Rubber, he also transferred 112 trabajadores (workers) (79 picadores and 33 jornaleros (day labourers)) and 33 trabajadoras mujeres (women workers) with the debts which they owed to him totalling 13,794 bolivianos.69 Effectively, this was the sale of human beings tied to the barracas by their debts. The contracts previously drawn up by Franck and used by Tambopata Rubber provided that the picadores; would pay interest at the rate of 2% per month in the event of any breach of contract; renounced the legal code of their own area and submitted to local law; and secured the performance of their enganche contracts with their “person and the best of their goods”.70

Caucheros and other labourers were paid for their services on Sundays with lead fichas (tokens) which could only be used in the company almacenes.71 Prices for food at San Carlos were high.72 Lawrence boasted that the indigenous workers did not understand money or weights. He swindled them when bargaining for shot and mules. The caucheros were paid less than the going rate for their rubber, while being swindled over its weight.73

The extent of the deception was described graphically by Murray while he was staying at the Tambopata provision station, a week’s journey up from San Carlos,74

Twelve new picadores arrive en route for San Carlos; [the] saddest site yet seen; they are so fat and happy, such a contrast to those seen below. They are sturdy fellows with long black hair, mostly very stupid looking, but one or two smart jocular looking youths among them. Food is issued to them, as much as they want and can carry. It is charged to them at a high rate, to be paid off in rubber. They don’t realise this and have no idea what they are going to, terrible labour, diseases, starvation, in most cases death. Their journey down is a triumphal procession; at the various agencies they get as much food as they like, they never had such a time in their lives; there is nothing to indicate the burden they are laying upon themselves; they imagine this easy full-fed time will continue. There is great fun over the issue of food to them. Their names are put on a list. Each kind of food is taken in turn; Jose [a clerk] reads out the names and each comes forward and claims his quantity; Chuno... rice, maize, cheese, coca (everybody takes it), sugar, coffee and so on. They are beaming with satisfaction. There is great packing, unpacking and repacking in various cloths. Then they settle down to an orgy of eating, cook and eat, cook and eat, for days. They live in a tambo down on the pampa; some have flutes and they have a right jollification. So little do they understand the value of food that one old fellow, having bought cheese at such a price that every pound probably meant a week’s work for him was selling it at a few cents a pound to the people about the place, and thought he was doing well. When they finally went, they were staggering under their loads; some had bought 100 lbs weight, one about 150 lbs. [The next day] Thirty-six fresh picadores arrive; go through the same performance as the other lot, but it is a bigger jollification. Food is not so plentiful and they don’t take quite such big loads… The picadores lie there, fluting and eating.

Tambopata Rubber sought to recover the debts of any workers who fled against their property and via sub-prefects and any new employers.75 Even in death, workers were bound by debt. On 26 September 1910, Vargas, a guard who had been working at Marte for over two years, had a brain haemorrhage and died while taking a bath in the river. Franck wrote to Lawrence

He has left a wife and three orphaned children. The family of the deceased overwhelm me with their complaints and cries and they demand that I give them at least something to be able to support their little offspring… I would like you to tell me if the deceased has left any balance so that his family can be protected.

Lawrence replied, “This ill-fated employee has not left any balance in his favour. On the contrary, he has died owing us a sum”.76 The Tambopata Rubber Syndicate actively pursued relatives of other workers who died to recover outstanding enganche debts - on at least one occasion forcing them to sell their home.77

Rubber Extraction

The trees in the region of San Carlos and Marte from which the caucheros harvested rubber were cauchous (castilla ulei). Unlike shiringa rubber (hevea brasiliensis), which is tapped, latex from cauchous was obtained by felling the trees, so that their trunks were supported diagonally by other branches and the latex drained into a hole in the ground, where coagulation was aided by mixing it with the juices of local lianas.78 Yields varied. An average cauchou tree produced between 25 lbs79 (an arroba) and 44 lbs of rubber. Larger trees produced from 50 to 75 lbs. In three days, a “good cauchero” could cut down and draw off the latex from three trees. Due to the climate, the main period of rubber production was from January to July as, during the rainy season, water prevented coagulation of latex. In a six-month season, a cauchero could collect 3,300 lbs of rubber.80

The castilla trees did not survive the rubber collection process. Most available trees were destroyed. It was a form of deforestation which was unsustainable.

The River Tambopata was not navigable between San Carlos and Marte. Although Fawcett and his party did travel downstream by balsa raft from Marte, it was not a viable method for exporting rubber.81 For the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate, the only means of ingress and egress for people, supplies and rubber was overland. So, men carried arrobas of rubber uphill on the path from Marte to San Carlos. Fawcett referred to them carrying loads of 150 lbs each.82 It was then loaded on to mules for the onward journey. Initially, rubber was exported via Santa Cruz in Bolivia, but after the boundary was settled, it went by rail from Juliaca via Arequipa to the Pacific port of Mollendo. Until the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, cargo was off-loaded onto the railway across the Isthmus, before being re-loaded at Colon for the final leg of the journey across the Atlantic.

Food

There were chacras of maize and bananas at San Carlos and Marte. 83 Food produced on the Altiplano, such as chuño (potato frozen in the open air at night and then dried in hot day time sunshine), chalone (dried sheep) and flour for bread, was brought down to San Carlos by mule. The company also had price lists for more exotic imported items, including evaporated milk, tea, salmon, sardines, English ham and Californian flour.84 Lawrence had cigars and Egyptian cigarettes delivered to San Carlos.85

Although Fawcett and Murray ate maize, chuño, bread, eggs, sopa, chalone and even tinned peaches at San Carlos, they complained that food was always in short supply.86 Fawcett wrote, “The table at San Carlos is very poor… Lawrence is fat and well-fed looking; but he has a private breakfast before the public one.”87 Fawcett managed to purchase a little maize and chuño, “but paid a vast sum”.88 However, the position for the peones and picadores bore no comparison. It was dire. “There is serious possibility of trouble with pickers if food supplies don’t come in soon. There is at present 1 week’s supply of food and no more… all food left in barraca gone!… little to eat. Still semistarvation… Great paucity of food here. Can’t get enough to eat”89

Food availability at Marte was even scarcer.90 “We found Marte in a state of starvation... Snor Neilson, the Bolivian of Scandinavian descent who ran the place, only had about a quart of maize left in his stores. The labourers had existed on leaves and grass for some time”.91 Costin wrote, “We soon were disappointed to discover we should be unable to “feed up” in this place, for it was occupied by some 150 Indians from the Altoplano (sic), all in a state of semi-starvation. Rice & maize was the only food”.92

Fawcett noted in November 1911 that there were no provisions at all at Marte and was told that there were often periods of three days without any food. That year, four or five men died of starvation.93 By 1911, the Marte mayordomo was leading raiding parties to rob the banana trees of the Ese Eja in the neighbouring Heath Valley.94 At times, that was impossible. In January 1912, he wrote that there were ninety men who were so sick with hunger that “they could not be moved to go for supplies”.95

Fawcett concluded, “It seems [an] extraordinary thing that such things can be - to work 300 men without food and to depend on robbing the Echocas’ chacras… If it were not for the savages’ plantations the business could not go on… Marte hardly pays enough to warrant the cost of food”.96

Health

Given the climate, predatory insects, poor nutrition, the lack of sanitation and the absence of any doctor or medical assistance in the region,97 it was inevitable that there would be serious health problems on the two barracas. Lawrence suffered “severe attacks” of “dangerous” fever.98 He also caught espundia, a form of leishmaniasis caused by leishmania braziliensis, a parasitic insect which burrowed under the skin. On one on his legs, there was a white patch half an inch across where someone had cut away the skin and flesh to cure him.99 Costin also suffered from espundia which was eventually cured at the London School of Tropical Medicine. All the Europeans suffered from sututus, maggot-like larvae of the botfly, which grew under their skin.100 Both men and mules were bitten by vampire bats, causing ugly wounds which streamed with blood.101

Again, the position of the indigenous workers was far worse. The company’s own records frequently refer to illness and death. In 1910, ten percent of Tambopata Rubber Syndicate workers died, as a result of disease and hunger.102 There are also references to the debts owed by 134 workers who had died.103

Fawcett described a group of labourers from Marte arriving at San Carlos as “a grizzly, weak, thin, diseased crew”.104 There were many cases of malaria and beri beri.105 In 1911, there was a severe outbreak of fever at Marte which caused Fawcett’s party to avoid the barraca and camp nearby.106 He described some thirty indigenous workers lying “in a filthy shed … in various stages of collapse, putrid with boils and other disorders”.107 Sejtiti, which Fawcett described as a form of leprosy, breaking out in running sores and soft warts, was common.108 Terciana was also a problem.109

Fawcett also noted, “Many of the men have become earth eaters. They die in about 2 years”.110

Lawlessness

The area was lawless. Fawcett wrote, “The law is a dead letter in the forest”. “Murderers abound amongst the men of this barraca. The authorities neither have the power nor apparently the will to punish”.111 Indeed, until the boundary was settled, it was not clear whether the Peruvian or Bolivian authorities had jurisdiction over the area. Lawrence used to tell people that “The Tambopata Rubber Company… [was] not quite sure if [the barracas were] in Peru or Bolivia”.112 Many men, including Ese Eja picadores, had guns, both for hunting and self-protection. In September 1910, 44 Winchester rifles which Lawrence had ordered arrived.113 One of the Boundary Commission surveyors wrote, “Money is of no use when treating with the Indians in the upper Heath, Marte district. The presents they appreciate most are; Shot gun (muzzle loader) powder and shot; Winchester rifle, with ammunition”.114

One day, “A man came in [to San Carlos] who blew off his arm with one of the rotten guns supplied. He amputated it clean with a machete and cured it by dipping it in copaiba oil which is generally used here as a curative”.115 Lawrence was among those who supplied escopetas (shotguns) to locals.116

In so far as the authorities had any influence, they tended to support the influential and powerful. Fawcett wrote about “the farcical application of laws” and about a U.S. citizen “who shot an Indian in the plaza of Sandia ‘for fun’ and gave the judge 50$ [sic] to do nothing”.

[A] a certain foreigner… being in high spirits as he rode across the plaza… whipped out his six-shooter and shot dead an Indian squatted against the wall, occupied in the consumption of his daily meal of maize. Somewhat sobered by the act, the foreigner dismounted, and, shoving a few sovereigns into the Indian’s mouth, continued his journey, whistling… [O]n being confronted by the sub-prefect and local judge, [he] promptly offered a sum of fifty pounds, with a further remittance of one hundred and fifty pounds… to square the affair. The offer was accepted and some verdict equivalent to “justifiable homicide” duly signed”.117

Although a Peruvian law passed on 23 November 1909118 prohibited political authorities from intervening in any way in the contracting and services of peones or workers of any class in public or private work, it was ignored on the Tambopata.119 The company’s papers contain many examples of public officials being pressed to procure men. For example, on 22 April 1911, Lawrence wrote to their agent in Sandia requiring him to ensure that the sub-prefect hurry up the despatch of quepires (Quechua for “ants”, but here meaning “porters”).120

Oppression on the barracas

Severe beating was common on rubber estates. Fawcett, Murray and Costin all noted with disapproval that Lawrence frequently flogged workers. Fawcett wrote, “The [corregidor] of this place tells me it is common knowledge that Vaca Dias used to flog his men to death and at times tie their hands behind their backs and their feet together and throw them in the river. Hence Laurence’s predilection for the whip”.121

Murray stated, “Flogging is practiced at San Carlos, though we could not know to what extent, as a good face is put on things for our benefit. Lawrence, however, uses a whip on the house ‘boys’ and often without justification. For instance, Costin’s pistol was stolen. Lawrence whipped the three house-boys, without having any reason to suspect them”.122 “[T]he unfortunate Indians who act as [porters] are driven in the cruellest and most inhuman fashion, many dying on the road from weakness or fevers contracted in the lower country. The... collectors who accompany them flog them unmercifully”.123

Fawcett noted that, “In Peru the punishment for whacking an Indian is some years of prison but the Indian has to put up 500 Peruvian soles to state his case”.124 He described how one of the bookkeepers at San Carlos beat an indigenous worker so badly that complaint was made to the authorities in Sandia. However, in accordance with the law, the book keeper insisted that the victim deposit 500 soles against the expenses of the prosecution. He was unable to produce that sum and instead the book keeper accused him of calumny. He was imprisoned for eight months, but died after four months.125

Lawrence “bought” people. He boasted to Murray that “he bought the woman” he kept at San Carlos for 150 bolivianos.126 He also complained that a macho (male) that he had bought from Franck had escaped.127 Fawcett wrote, “The savages bring in their children to sell frequently”.128 On one occasion, Lawrence exchanged two guns, each worth nine shillings and six pence (47½ pence) for two small boys. The boys later ran away, but when ten local men came into the barraca, Lawrence had all their escopetas confiscated until they returned the boys.129

Murray recorded, “Lawrence has a dwarfish Indian boy of uncertain age… At dinner he makes him do what he calls a song and dance. His treatment is not calculated to improve him”.130

On occasion, the workers rebelled against this regime. In August 1909, while Lawrence was away from San Carlos, one of the other mayordomos complained that some of the picadores were “extremely insolent and unruly” because they were being made to tend the chacra and carry goods, work which paid less well than rubber collection. On 4 September 1909, there was “a serious insurrection” involving one hundred workers at Marte. They fled, after burning the almacen and account books. Franck wrote that “luckily a few days before the revolt broke out… Mr. Lawrence had left for Arequipa, because [if the crowd had succeeded in killing] him, nothing of the Syndicate’s property would have escaped [being] destroyed. The mayordomos [managed] to restore order but at the cost of several lifes (sic) and wounded”. One of the workers who returned surrendered and went down on his knees, begging for forgiveness. Asturizaga, an empleado, shot and killed him as he knelt.131

The company’s account books recorded the following expenses occasioned by the huelga (strike), see Table 1.

Table 1 Expenses occasioned by the strike

| Debts of the 4 deceased | B/.236.50 |

| Transmission expenses | B/.152.90 |

| Expenses in pursuit | B/.380.91 |

| Losses in the store | B/.359.10 |

| Other | B/.2,778.40 |

| Total | B/.3,808,81 |

Source: “Franck letter to the Secretary, Tambopata Rubber Syndicate”, 9 March 1910 Correspondencia Franck and Marin, La explotacion del caucho, pp. 156-158 and Anexo.

Over the years, many picadores and peones tried to flee San Carlos and Marte. Letters from Lawrence made frequent reference to fugitivos and their debts. Tambopata Rubber, with the help of the authorities, pursued them and ensured that they were returned to the barracas.132 On 7 April 1908, seven workers escaped. On 28 November 1908, another seven fled. In September 1909, there was “a massive flight” following the insurrection. Between June 1911 and May 1912, 45 men fled. When recaptured, they were beaten and fined one boliviano or one and a half bolivianos for each day of absence. The fines were added to their debts.

Denunciation of the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate

Towards the end of 1910, three picadores escaped. They complained about their treatment to Marcos 2° Cortés, the mayordomo of the Inca Rubber Company at Cojata. He informed Pedro Zulen, Secretary of the Asociación Pro Indígena, who wrote to the Puno Prefect

Manuel Machicao, Mariano Tito, and Modesto Villa, all three natives of the Department of Puno, have been subjected to corporal punishment, Machiao and Villa at the barraca “Marte” and Tito at the barraca “San Carlos”, which belongs to the Sindicate “Tambopata Rubber”. The… workmen were punished for the least reason… A certain Braulio Peñaranda is named as the chief tormentor of the labourers; the provision of food is not sufficient for the people, who live on half-rations, and are forced to work from 6 in the morning to 6 in the afternoon, so that many get ill with forest diseases.

The Asociación Pro Indígena petitioned for men to be allowed to leave the barracas because “at present the labourers cannot leave… whether or not they owe a debt, but are kept like slaves, condemned to die for want of resources, without receiving any aid”.133

Zulen also informed Jerome, the British consul. He received confirmation of the allegations from two monks who were members of the Papal delegation to Peru. Jerome wanted to publicise the allegations, but “could not induce anybody to come out in the open and put their signatures to what they stated”.134 Indeed, the “sub-prefect was imprisoning natives who had [accused him of being an agent of Tambopata Rubber] and was threatening to flog them to death unless they withdrew their accusations”.135

This issue was discussed at an Asociación Pro Indígena meeting on 20 January 1911.136 It resolved to send details to the Anti-Slavery Society in London under the title “La Esclavitud en la Montaña”137 (Due to “an involuntary clerical error” (Pedro Zulen’s words), publicity of the allegations wrongly named Inambari Para Rubber Estates as the company responsible, not the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate.) The allegations were published in El Deber Pro-Indígena, the Asociación’s newspaper, and repeated in El Comercio and La Prensa.138 El Comercio stated that the “abuses reached the point of ripping indigenous people out of their homes to enslave them in the montaña”.139 The Times published a telegram from its Lima Correspondent stating that the President of the Asociación had petitioned the Peruvian Government to punish and put a stop to, the abuses.140 The Asociación Pro Indígena specifically named La Casa Ricketts. In response, Ricketts wrote to Zulen referring to the “innocence” of the Syndicate; the “falsity” of the allegations; and demanding “a public rectification”. Ricketts also instructed the company’s lawyer, Dr. Camino, to protect its interests. In London, Ernest Bartlett, the Company Secretary, wrote to the Under Secretary of State at the Foreign Office, stating, “the alleged ill-treatment of natives can hardly be taken seriously”; “there is not an iota of truth” in the accusation; “Cortes [is] a man well known for his disreputable conduct”; the allegations were driven by internal “political rather than humanitarian considerations”; and that he had “no doubt nothing in the nature of an outrage has taken place on [their] property”.141

Jerome asked the British Foreign Office to investigate the company and tried to persuade Sir Roger Casement to travel to the Tambopata region. However, the Foreign Office instructed Jerome to ignore the “Indian question in South America” and so he decided “not [to] go any further in the matter.142

The Company’s Financial Position

As a limited company, the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate was a shell which allowed profits to be made (if there were any) without risk of liability on the part of the investors. Although the capital advanced by any investor was always at risk, that was the nature of business. The Gibbs partners were able to profit from the charges made to the company (commission on the sale of rubber imported and manufactured goods exported; interest; for the provision of office space and secretarial work; and for postage and telegrams) but were legally protected from being sued by the company’s creditors. When the company was no longer profitable, they could cut their losses by liquidating it and move on to more profitable investments.

The “Rubber Boom” which had begun in the last decade of the nineteenth century continued during the first decade of the twentieth century. Rubber prices rose steeply. In April 1908, Gibbs quoted a price of three shillings per pound for cauchou rubber.143 In December 1908, they were quoting a market price of four shillings and eight pence per pound.144 By 1910, the price was an “incredible” twelve shillings per pound.145

From 1908 to 1911, according to the company accounts, the value of the company’s rubber stock increased year on year (Table 2):

Table 2 Value of the company’s rubber stock

| 31 July 1908 | £3,273 6s 5d |

| 31 July 1909 | £7,722 6s 1d |

| 31 July 1910 | £9,908 17s 2d |

| 31 July 1911 | £11,937 0s 0d |

Source: Board of Trade. BT 31/18084/93238. These figures reflect the value of unsold rubber; i.e. rubber in transit from San Carlos and Marte to England.

However, the quantity of rubber extracted peaked in 1911 and then declined. See Table 3 and Table 4:

Table 3 Net proceeds from the sale of rubber Tambopata Rubber Syndicate rubber sold by Gibbs

| 1909 | £5,481 9s 6d |

| 1910 | £4,332 3s 11d |

| 1911 | £10.286 13s 5d |

| 1912 | £9,686 15s 9d |

| 1913 | £3,069 6s 4d |

Source: “General ledger, Second series, F2 Calendar years 1909-1913”, Gibbs Papers CLC/B/012/MS11054/022. There were twelve pence per shilling; twenty shillings per pound. One shilling was worth five pence in current British currency.

Table 4 Total Tambopata Rubber Syndicate production

| 1907 July to December | 4,527 lbs |

| 1908 January to July | 18,192 lbs |

| 1909 Six months | 46,292 lbs |

| 1910 Six months | 53,086 lbs |

| 1911 Seven months | 7,309 lbs |

| 1912 Twelve months | 55,285 lbs |

| 1913 Six months | 21,273 lbs |

Source: Archivo Agrario, Tambopata Rubber Syndicate.

Despite the high rubber prices in 1910, the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate project was never economically sustainable.146 Gibbs claimed that the cost of producing rubber (duties, labour, etc.) was three times higher in South America than in the Far East.147 Even in the boom years, they had to provide additional credit for the company to run the gomales (rubber estates).148 Transport was too difficult and too costly. There was a shortage of labour. There was never sufficient food for the workers. The felling, rather than tapping, of trees meant picadores had to travel further and further to find rubber.149

The Tambopata Rubber Syndicate only ever made a loss. Each year the company’s trading deficit increased (Table 5):

Table 5 Company’s trading deficit

| 31 July 1909 | Loss from previous year | £935 10s 2d |

| 31 July 1910 | Loss from previous year | £1,278 12s 6d |

| 31 July 1911 | Loss carried to balance sheet | £2,696 4s 11d |

Source: Board of Trade. BT 31/18084/93238.

By January 1912, Gibbs had written down the value of each share from £1 to five shillings.150

The position was exacerbated by the dramatic fall in rubber prices as production in Asia increased. Between 1892 and 1910, the value of the 1910 1920 Para, Brazil 16,687 10,931 Manaos, Brazil 16,680 11,678 Iqiuitos, Peru 2,260 1,094 Mollendo, Peru 306 62 Peruvian rubber exported had risen from 1% of all exports to 30%, but exports fell dramatically in 1911 and practically disappeared in 1912.151

Tambopata Rubber tried to reduce costs and cut payments to picadores and other labourers, but the San Carlos and Marte barracas could not be made financially viable. Fawcett wrote, “There is nothing of commercial value known at present in the Peruvian forests other than rubber; and when the price of this drops below 3s. per lb. the industry is dead, even if it is boosted with forced labour”.152

Gibbs were making a profit, although the income they received as commission on the sale of imported rubber and exported goods was not substantial, viz. Table 6.

Table 6 General produce

| 1909 | £258 19s 4d |

| 1910 | £212 7s 7d |

| 1911 | £370 5s 4d |

| 1912 | £416 7s 2d |

| 1913 | £156 19s 9d |

Source: “Commission ledger F 1909-1911” Gibbs Papers CLC/B/012/ MS11066/002 and “Commission ledger F 1912-1913” CLC/B/012/ MS11066/003. These sums are the totals of commission on general produce (i.e. rubber), general goods sold, primage and decredere.

In addition, they were charging for use of offices and secretarial assistance, interest, postage and cables. However, this income was bound to decline as rubber prices fell. Also, the value of their capital investment was falling. By May 1912, Gibbs had already decided “to gradually liquidate the business as it is evident that such distant natural rubber forests will not be able to compete with the plantation rubber which is now being actively developed”. They kept that decision secret and deliberately did not tell Ricketts.153

Attacks on San Carlos

At the same time, the local environment in the area around San Carlos and Marte was becoming increasingly hostile.

In August 1912, the Boundary Commission surveyors heard that there was “inter-tribal warfare” on a small scale downstream from Marte. They did not witness any hostility, except perhaps a raiding party who were “visiting” local Ese Eja.154 Fawcett and his colleagues made no reference to this in their diaries.

On 19 May 1913, reports reached San Carlos that an unknown group of Ese Eja had been seen nearby. At midnight, an indigenous man, who lived in a hut three miles up the Colorado River, came into the barraca, and told Lawrence that some Ese Eja had appeared from the forest and, after talking to him and his wife, suddenly attacked them without provocation. They killed his wife and wounded him. He went into his hut to get his shotgun, but found the dead bodies of the other two occupants, an old man and a boy. The next day, Lawrence recovered the bodies and, a couple of days later, sent out a reconnoitring party. Two hours away, they found the footprints of eighty to one hundred Ese Eja and about thirty dogs. On May 22, Lawrence wrote to Sardon, gobernador of Tambopata, asking him to send men and arms. “We are in danger of being attacked at any moment… The matter is extremely serious”. The following days, more footprints were found and on May 28, “a band of forty savages” was located on a tributary of the Colorado River where they had been making arrows. Barraca employees and rubber pickers were “thoroughly alarmed by the situation” and sought safety in San Carlos. By May 31, Marte was evacuated and a field of fire cleared around San Carlos. Three pickets were mounted at night. Captain Nanson, a Boundary Commission surveyor, arrived and led out a group of fifteen men with shotguns contracted by Sardon, some rubber pickers with guns and some local Ese Eja. The insurgents left eastwards towards the Madidi Basin. Nanson considered that the threat was exaggerated.155

However, Lawrence wrote:

Even if the garrison comes, it is impossible to continue work. Picadores do not want to go to the mountains in any way to collect rubber… Soldiers will serve no purpose if there is no way to work. It would be very difficult to get new people to come. While we're gathered like we are currently in San Carlos it is unlikely that the savages will attack - but it is impossible to send people to collect rubber.156

On 16 June 1913, San Carlos was attacked. The attackers set fire to the almacen. The company abandoned San Carlos and Marte and Lawrence was “disengaged” in September 1913.157

The Dissolution of the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate

Bartlett, who was appointed as liquidator, wrote, “[T]he Syndicate owned Rubber properties right away from civilization in the montaña of Peru and Bolivia. These properties were suddenly raided by warlike Wild Indians: the Manager, his staff and workers fortunately made good their retreat after some loss of life. But no one has been near the place since, to my knowledge”.158 That was not though the whole truth. The company would have been forced to abandon San Carlos and Marte for economic and logistical reasons even if the barraca had not been attacked.

The last company accounts were filed on 7 January 1913. On 30 December 1913, a shareholders’ meeting of the company passed the following resolution, “It has been proved to the satisfaction of this meeting that the company cannot by reason of its liabilities continue its business and that it is advisable to wind up the same, and accordingly that the Company be wound up voluntarily and that Ernest Tierney Bartlett of The Hermitage, Dorney, Bucks be appointed liquidator”.159

Bartlett informed the Registrar of Joint Stock Companies that “nothing was salved and the lands are worthless”. Some of the mules which brought out the staff and some of the stores in depots half way up to the forests were sold locally. He continued, “My agents have been unable to recover these [debts], the buyers being un-get-at-able, but have extended the time for a year or two, and I am waiting to know finally if anything and how much may be definitely recovered before I have any data for accounts”.160

By February 1915, the debts owed by the company to unsecured creditors were £35,192 5s. 5d.161 The company was finally wound up in 1925.

Legacy

There is now no physical trace of the two barracas.162 San Carlos and Marte do not appear on modern maps of Peru. In the words of José Eustasio Rivera, “The jungle devoured them!”.163

Those Europeans who survived the First World War seem to have prospered. Antony Gibbs and Son made a significant capital loss on the dissolution of Tambopata Rubber, but had profited from the company until 1912. John Arthur Gibbs remained a partner until 1930, when he retired. Brien Cockayne became Lord Cullen and served as deputy governor of the Bank of England from 1914 to 1918 and governor of the Bank of England from 1918 to 1920. The firm continued trading as a family partnership until 1973 when it was floated on the London Stock Exchange as a public limited company. It was acquired by HSBC in 1981. The relationship between Gibbs and Ricketts continued for many years, with the export of wool, cotton, leather and silver and the import of manufactured goods from Europe.164

Even before the abandonment of San Carlos, Gibbs’ London office were recommending Lawrence for “fresh employment”.165 He did not serve in the First World War, but moved to Chile and worked as a merchant and manager. In 1925, he was employed by Gibbs as the manager of a nitrate oficina.166 Ashton was wounded in the First World War, but in 1920 married the Chilean born daughter of a Cornish mining engineer. He lived the rest of his life in Peru or Bolivia; in Cusco as a commercial agent; in La Paz as a merchant and the joint owner of El Condor department store; and in Arequipa in retirement.167

Fawcett became famous as an explorer, but disappeared without trace in the Brazilian jungle in 1925.168 In 1913, Murray joined a Canadian scientific expedition to the Arctic, but went missing, presumed dead. Costin emigrated to Australia. Toppin of the Boundary Commission was killed in the First World War.

Inevitably, no identifiable individual records of the Ese Eja or other indigenous picadores or peones who worked at San Carlos and Marte remain and there are no oral histories. The Ese Eja population was decimated both before, during and after the “Rubber Boom”.169 According to the 2017 Peruvian census, nationally, 440 people self-identified as Ese Eja according to their customs and ancestral heritage; 212 people stated that they spoke the Ese Eja language as their mother tongue.170 Vellard referred to some twenty families living in two villages at Palma Real close to the Heath River in 1974.171

Conclusion

Unlike the Putumayo atrocities, the abuse perpetrated by the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate remained largely hidden. A combination of factors including; the remoteness of the Tambopata border region; the error by Pedro Zulen in misnaming the company; the defensive activities of Ricketts in instructing lawyers in Lima and of Gibbs in lobbying British politicians; the rapid insolvency of the company; and the approach of the British Foreign Office meant there was less mention of its activities in the British and Peruvian press.

Nevertheless, despite the formal, legislative abolition of slavery and the company’s vehement denials, the independent accounts of Fawcett, Murray, Costin and Jerome and the weight of other documentary evidence make it clear that, by any definition, the forced enganche in San Carlos and Marte was a brutal form of slavery.172 The conditions in those barracas may not have been as sadistically barbaric as the atrocities committed on the Putumayo, but they were inhuman and degrading and there was clear British involvement in the provision of capital and the organisation of the enterprise. The British government, through its consul in Callao, knew what was going on. There is nothing to indicate that the Gibbs partners were directly aware of the extent of the oppression of indigenous people, but the Ricketts partners must have known. Indeed, Walter O. Simon of Stafford and Co. wrote, “the Manager, (who, I am sorry to say, is an Englishman) tried native methods”.173 Lawrence’s “evil” Göring-like conduct was unacceptable even by the standards of the times, as evidenced by the comments of Fawcett, Murray and Costin, but perhaps it was inevitable that a brutal system brutalised the oppressors at the same time as it oppressed the victims. Fawcett (reflecting the attitudes of the times) put it this way:

The rubber trade of Peru, in fact, is demoralizing at its best, and calculated to blunt the finer feelings of the best of men, who find it far from easy to control a large number of contracted Indians, who, looking for a respite from a hopeless struggle against overwhelming odds on the [Altiplano], find when it is too late that rubber gathering is not what it was cracked up to be by well-commissioned labour contractors.174

Fawcett was one of the few disinterested outsiders to travel extensively in the Peruvian and Bolivian Selva. There is no reason to doubt his observation that real slavery, albeit covered by quasi-legal formalities, was the rule.175 Indeed, there is every reason to conclude that the activities of the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate, backed by British capital, were typical of the rubber companies operating in the Amazon Basin at that time. Indeed, that was confirmed by Lucien Jerome.

From a modern perspective, Enock’s overtly racist, anti-Iberian sentiments cannot be justified and constitute no possible explanation for slavery. There are many reasons why this form of slavery persisted, including; attitudes prevalent at the time176 (e.g. racial hierarchies and theories of Social Darwinism);177 extreme geographic and climatic conditions; physical remoteness and the absence of law and order; an imbalance of power and technological knowledge; lack of education and ignorance of commercial practices; shortage of free and willing labour; and the financial pressures of the rubber trade.

One only has to consider the prevalence of people trafficking, modern slavery and debt bondage/indentured labour at the present time178 to appreciate that slavery is not just a historic phenomenon. In 2021, worldwide, there were fifty million people in situations of modern slavery on any given day.179 In England and Wales, the number of potential victims of offences contrary to the Modern Slavery Act 2015 who were referred to the National Referral Mechanism each year rose from 2,340 in 2014 to more than 10,000 in 2020.180 In 2005, the International Labour Organisation estimated that there were some 33,000 people, mostly from indigenous ethnic groups, subjected to forced labour in illegal logging camps in the Peruvian Amazon Basin.181 The “timber bosses… employ deception to entrap workers in a cycle of debt and servitude, that can be passed on from one generation to the next”.182 It is clear that some of the factors which led to the abuse perpetrated by the Peruvian Amazon Company and the Tambopata Rubber Syndicate still exist today and that, without strong and effective government regulation, they can cause similar harm.

Newspapers and journals

“La condicion de los indios en la montana”, El Comercio Lima, 9 March 1911.

“Letter from Zulen”, El Comercio Lima, 12 April 1911.

“Rubber-Collection In Peru, Allegations Of Cruelty”, The Times London, 30 May 1910.

“Rubber Companies and South American Natives”, The Times London, 13 February 1911.

“Rubber Companies and South American Natives”, The Times London, 16 February 1911.

”Rubber Companies and South American Natives”, The Times London, 17 April 1911.

“The Putumayo Atrocities, A South American Congo, Sir Roger Casement’s Report Published”, The Times London, 15 July 1912.

“Political Notes: The Putumayo Atrocities”, The Times London, 25 July 1912.

“The Rubber Traffic in Peru. A Widespread Evil”, The Times London, 26 July 1912.

“The Rubber Traffic in Peru”, The Times, 31 July 1912.

“’The Devil’s Paradise’ A British-Owned Congo”, Truth London, 22 September 1909; “’The Devil’s Paradise II’ Statements By The Company”, Truth London, 29 September 1909.

“The Peruvian Legation And ‘The Devil’s Paradise’”, Truth London, 6 October 1909.

“In the Heart of South America”, Wide World Magazine London, July-Oct 1912.

Primary sources

Anti-Slavery Society Papers, Bodleian Library, Oxford MSS Brit Emp. S.22 G319.

Arequipa Cathedral, Records.

Ashton Private Family Papers.

Base de Datos Oficial de Pueblos Indígenas u Originarios, Perú Ministerio de Cultura.

Correspondence respecting the Treatment of British Colonial Subjects and Native Indians employed in the collection of rubber in the Putumayo District, London, July 1910-June 1912, Miscellaneous Parliamentary Papers, No. 8, 1913 [Cd. 6266].

Costin, Corporal Henry, Letters (“Costin Letters”). Costin Private Family Papers.

Fawcett, Colonel Percy, Diaries (“Fawcett Diaries”). Torquay Museum, AR4507 and AR4508.

Franck, Carlos, Archives and Correspondence (“Correspondencia Franck”). Private Papers of Pablo Cingolani, La Paz.

Gibbs, Antony and Son Papers (“Gibbs Papers”), London Metropolitan Archives; General ledger, Second series F1 CLC/B/012/MS11054/021; General ledger, Second series; CLC/B/012/MS11054/022; General ledger, Second series, F2; LC/B/012/MS11054/025; Agreements, chiefly foreign and relating to Latin America, with papers appertaining F5; CLC/B/012/MS11068/002; General private out-letter book to South American branches CLC/B/012/MS11116/001; and General private out-letter book to South American branches CLC/B/012/ MS11116/002.

Gibbs letter to Eduard Lembke, Peruvian Consul General, London, 3 April 1911, Cartas de varias casas comerciales a la legacion del Peru en La Gran Bretana, Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores, Lima, Caja 613, File 10, 5-17-R.

Hansard, London. vol. 41, col. 2914, 6 August 1912; vol. 41, col. 688 19 July 1912.

Jerome, Lucien, letters to Casement, Sir Roger, National Library of Ireland, Dublin. MSS 13,073/29/ii and 13,073/29/iii.

Mercaderia Otras Series Sociedad Commercial Ricketts, Archivo Agrario (“Archivo Agrario, Sociedad Commercial Ricketts”), Archivo General de la Nación, Lima.

Murray, Doctor James, Transcript of Diary (“Murray Diary”). National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh. Acc.12696/63.

Museo Histórico Nacional, Chile, Fotografía Patrimonial.

Nanson, Captain M. R. C., of the Peruvian Commission “Brief Description of the Frontier Country” Royal Geographical Society, London, Rgsu213480.

Tambopata Rubber Syndicate, Memorandum and Articles, 1907, Board of Trade, London, National Archives, Kew. BT 31/18084/93238.

Tambopata Rubber Syndicate papers, Archivo Agrario, (“Archivo Agrario, Tambopata Rubber Syndicate”), Archivo General de la Nación, Lima, uncatalogued.

Toppin, Capt H S, Diary Royal Geographical Society, London, Rgsu213480.

U.K. Census Returns 1881 and 1891.

U.K. Government Annual Report on Modern Slavery, 25 November 2021.

Edited sources

Hardenburg, W. E., The Putumayo, The Devil's Paradise, London, 1912.

Holdich, T. H., Peru-Bolivia Boundary Commission 1911-1913 Reports of the British Officers, Cambridge 1918.

Markham, Sir Clements, “The Land of the Incas”, The Geographical Journal, vol. 36, núm. 4, 1910. doi: 10.2307/1777045

Rivera, José Eustasio, La Vorágine, Bogotá, 1924.

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information, vol. 1899, núm. 149/150 (1899).

Suárez, Nicolás, Anotaciones y documentos sobre la campaña del Acre, Barcelona, 1926.

Schurz, William Lytle, Hargis, O. D., Manifold, Courtland Brenneman and Marbut, Curtis Fletcher, Rubber Production in the Amazon Valley, Washington D.C., 1925.

Tizón y Bueno, Ing Ricardo, La Hoya Peruana del Madre de Dios, Lima, 1911.

U.S. House of Representatives Slavery in Peru Message from the President of The United States Transmitting Report of the Secretary Of State, with Accompanying Papers, concerning the alleged existence of slavery in Peru, Washington D.C., 7 February 1913.

Vellard, Jehan, “Los indios guarayos del Madre de Dios y del Beni”, Boletín del Instituto Riva Agüero, núm. 10.

Von Hassel, Jorge, “Importancia de la región amazónica y del proyecto de un ferrocarril entre Piura y el Pongo de Manseriche”, Boletín de Sociedad Geográfica de Lima, tomo XII, trimestre I, Imprenta y Librería de San Pedro, Lima, 1902.

Woodroffe, Joseph F., The Rubber Industry of the Amazon and how its supremacy can be maintained, London, 1915.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)