Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Contaduría y administración

Print version ISSN 0186-1042

Contad. Adm vol.59 n.1 Ciudad de México Jan./Mar. 2014

The hidden face of mobbing behavior. Survey application of the Cisneros inventory in a maquila facility in Mexico

La cara oculta del mobbing. Aplicación de la escala Cisneros en una planta maquiladora en México

Blanca Rosa García Rivera*, Ignacio Alejandro Mendoza Martínez**, John L. Cox***

* Universidad Autónoma de Baja California. blanca_garcia@hotmail.com

** Facultad de Contaduría y Administración, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. alexmemi@unam.mx

*** University of West Florida. lcox@uwf.edu

Fecha de recepción: 11.10.2012

Fecha de aceptación: 23.04.2013

Abstract

The importance of this paper lies on the identification of the components of mobbing behavior at the maquila industry. Although the mobbing factor has been widely studied, studies made in the outsourcing industry in Mexico are scarce. The aim of this research was to diagnose the degree of mobbing that the surveyed employees showed as well as individual differences among the employees that suffered this problem. This paper applied the Cisneros inventory. The authors tested the original 43 item version with data collected from a sample of 150 direct employees working at a maquila production center for Radars and GPS Instruments in Ensenada, Baja California. Even though results show low levels of mobbing since only 8% of the surveyed employees experienced high degree of the harassment, 138 of the surveyed employees have suffered at least one of the mobbing behaviors from coworkers in the last six months. Correlations showed high significance between the variables of the model.

Keywords: mobbing, bullying, harassment, workplace violence, workplace aggression.

Resumen

La importancia de esta investigación radica en la identificación de los principales comportamientos relacionados con el acoso laboral en la industria maquiladora. Aunque el acoso laboral ha sido estudiado por numerosos investigadores, los estudios en la industria maquiladora sobre este fenómeno son escasos, a pesar de que es un fenómeno que se presenta muy frecuentemente en esta industria. El propósito fue diagnosticar el nivel de acoso laboral que presenta una muestra de empleados de una empresa maquiladora, así como sus diferencias individuales. Se trata de una investigación transversal descriptiva. Se aplicaron 150 cuestionarios en una empresa maquiladora de Ensamble de Radares y GPS en Ensenada, Baja California. Se usó el cuestionario Cisneros con un total de 43 reactivos con escala de Likert. Se encontró que aunque el nivel de mobbing presente en la muestra es bajo, pues sólo el 8% de los encuestados manifestó altos niveles de mobbing, 138 de los empleados encuestados han sufrido al menos un incidente en los últimos seis meses. El acoso se manifiesta principalmente en forma horizontal, es decir, de sus propios compañeros. El estudio demostró correlación alta y significativa entre las variables analizadas.

Palabras clave: acoso laboral, mobbing, presión psicosocial, acoso psicológico en el trabajo.

Background

Mobbing behavior has been documented in different settings under labels such as bullying and workplace bullying. While various authors (Agervold, 2007; Yildiz, 2007) discuss differing terms and nuances, there is a general agreement upon the outcome of mobbing, no matter the term used to define it. Persons who suffer from mobbing behavior may experience emotional distress or post-traumatic stress disorders. Mobbing is a term that is used to describe certain toxic behaviors within organizations that illustrate extreme elements of violence prone environments.

Introduction

The maquila industry in Mexico has grown to become major production centers for large corporations where the employees are taken as a resource that fuels the industry's growth. The international corporations that manage their outsourced processes from a distance have relatively little knowledge and virtually no direct control over the abuse that employees suffer from their coworkers and supervisors on a daily basis (García y Cox, 2005). The main forms of mobbing behavior found in this research were isolation, blaming, heavier workloads, and diminished self esteem.

Although extensive research has been conducted to study mobbing behavior in organizations, empirical research in Mexico has not led to firm conclusions regarding its antecedents and consequences, at either the personal or organizational levels (Topa y Morales, 2007). The authors' extensive literature search yielded 86 empirical studies with 93 samples. Results supported hypotheses regarding organizational environmental factors as main mobbing predictors.

According to Melia (2006), mobbing is defined as a pattern of continuous aggressive behavior, actions and/or omissions, performed by some members of the social setting. Some researchers accept the term mobbing only if the victim has been suffering mobbing behaviors, e.g., rumors, isolation, changes in job demands, weekly for at least six months.

According to Einarsen, Hoel, Zapf and Cooper (2003) mobbing behavior is a very painful form of aggression at work. For the term to be considered appropriate in a specific situation, some well-known mobbing behaviors have to occur repeatedly and regularly, at least once a week, and over a period of time lasting more than six months.

No matter its location, the assembly industry has always been characterized by great dynamism in its operations, and this is certainly true for the large corporations that have opened production centers in Mexico. These corporations have benefited from the advantages offered to them by the Mexican labor and industrial environment. These advantages include, but are not limited to, low wage costs coupled with high productivity, plus manpower that is enabled and available. The corporations' managers basically limit the locations and the organizations to production centers where decisions are highly centralized, where technology allows repetitive operations of high intensity, and where employees are under great pressure to fulfill the production quotas imposed to them; all strategies are used to make employees more productive upon threat of termination. Labor laws and rules are such that employees who do not meet these criteria are forced to leave the organization without the organizations' having to pay termination costs.

Mobbing behavior has been a problem for most organizations all over the world. Due to the great importance that it has in this industry, and that it has been ignored in Mexico until now, this investigation's aims are to analyze the problem, characterize it, and verify its possible consequences on employees who face it day after day without finding support or answers in their organizations, companions, and supervisors. In addition, this investigation considers (1) sources of labor pressure (or harassment), (2) manifestations of psycho-social stress at personal and organizational level that the mobbing behavior generates.

The association of mobbing behavior and leadership has been demonstrated by authors like Adams (1992a), Crawford (1999), Bassman (1992), Ashforth (1994), Barón et al. (1999), among others, although hostile, humiliating and intimidating behaviors have not been explored in investigations on direction and leadership (Rayner and Cooper, 2006). Therefore, it is observed that behaviors such as public humiliation, insults or isolation from the group are bound directly to a negative leadership. Other authors like Liefooghe and Mackenzie Davey (2001) mention in their Critical Theory of the Direction that power is a central element to explain the mobbing behavior, and its use is an evidence in the organization. The practices of supervision such as time control, allocation of the tasks, regulation of absenteeism, labor instability, or the threat of being replaced by machines, are interpreted by the workers as hostile and intimidating behaviors. Thus, individual employees and employee groups develop confronting strategies to defy certain systems of behavior by the organization. From a psychoanalytic approach, Thylefors (1987) mentions that mobbing behaviors are evidence of frustration on the part of the pursuer, and this frustration impels action against the victim.

Leymann (1997) makes a clear distinction between bullying and mobbing by stating that the bullying concept is very often characterized by physically aggressive acts. On the other hand, mobbing is characterized by more sophisticated behaviors, such as harmful treatment or harmful pressure on employees.

Understanding mobbing behavior in the workplace has been hard, since it is frequently related to bullying. What are the specific examples of harassing acts to differentiate aggressive-violent behavior vs. psychological, stressful harassment within the workplace? According to Von Bergen et al. (2006) related grievances of harassment understood as Mobbing relate to intimidating behavior.

Analyzing the mobbing behavior victims, Brodsky (1976) mentions three types of observed symptoms associated with mobbing behavior: a) physical sickness, b) depression, insomnia and low self-esteem, c) hostility, hypersensitivity, social isolation and nervousness, among others. Similar findings obtained by Fox and Spector (2005), Moon, Yela and Antón (2003), among others.

Mobbing also affects those who, without being direct participants, are observers of the mobbing behaviors. The observers show consequences like lower job satisfaction, lower productivity and decreased motivation (Elinarsen et al., 1994). Also, they present or display major stress levels, a negative perception of the labor climate, more role ambiguity and less autonomy (Vartia, 2001, 2003). Observing the mobbing behavior, increases their fear to become the next mobbing victim (Rayner, 1999).

As discussed above, a great number of models and research have been developed to explain this problem; nevertheless, in Mexico, this problem has been related to a variety of factors that include: globalization, liberalization of markets, high pressure focused on efficiency, popular organizational philosophies such as Total Quality and re-engineering, and finally, remuneration methods that encourage payment by piece. These challenges have led to an increase in the mobbing behaviors (Sheehan, 1996; McCarthy, 1996; Wright and Smye, 1997; Hereads, 2000; O'Moore et al., 2003, among others).

Methods

We developed a cross-sectional, descriptive and correlational research design to analyze mobbing behaviors at the surveyed organization, a high tech plant in Ensenada, Mexico that assembles radar and GPS systems. The products are integrated in final assemblies for different brands like B&G, Eagle, Lowrance, MX radar, Navman, Northstar and SIMRAD.

Data Sample

This plant employs more than 1250 employees in the high season. There were 550 employees working at the organization during the low season, when the questionnaire was applied. The sample was by simple random sampling and provided an 80 percent confidence level. Data were collected from 150 people (N=150), 129 women and 21 men, with ages ranging from 18 to 53 years. The population was predominantly female in this research. Women are known in Mexico for their detailed work and responsibility that leads to higher productivity rates. Most of the employees that participated in the survey were young fellows between the ages of 26 and 35 (54%). Also, 141 of the surveyed employees work in the production area, 2 are in managerial positions, 4 are office staff and 3 are janitorial workers. The questionnaire was given personally to all the surveyed employees, and the employees were selected at random. The greatest number of the employees had seniority at the company of 2 to 5 years (65%). Instructions for the correct interpretation and completion of the questionnaire were given to them. The survey application was authorized by the organization managers, and it was conducted during working hours in groups of 50 people who were called randomly to the department of human resources and given 15 minutes to complete the survey questionnaire. The survey was done during October of 2010 and the company received the results upon final completion. The sample represents 27% of the total population of the company.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was created by Piñuel y Zavala (2004), and it is known as the Cisneros scale. The Cisneros scale is a questionnaire made up of 43 items on a seven-point Likert scale that assess psychological harassment or mobbing at work. The range of the scale goes from never (0) to daily (6). Items deal with 43 different behaviors related to bullying, harassment and emotional abuse in the workplace (Individual Questionnaire on Psicoterror, Negation, Stigmatization and Rejection in Social Organizations). The content and development of violence and harassment in the workplace is explored in a periodic way by the questionnaire. This scale has the purpose to find different acts of harassment as well as the intensity of the damage caused to a victim, and its main objective is to determine the frequency of these behaviors.

We applied an Alpha Cronbach reliability test to the total items, finding a value of 0.989. The reliability test by subscale is shown in table 1.

As noticed in table 1, all the subscales have an alpha Cronbach reliability higher than 0.80. Also, we made a validity test using a factor analysis that grouped the items in 5 main variables as shown in table 2.

As noticed in table 2, the first factor, personal downgrading, explains the higher percentage of the variance. Also, in table 3, the factor analysis is shown:

Factorial solutions of most scales of mobbing indicate the existence of a factor that groups a lifted percentage of the variance. In our case, personal downgrading is the denominated factor that groups 17 items and explains 40% of the variance. The factorial analysis of the LIPT made by Niedl (1995) indicates that the first factor, i.e. personal downgrading, groups a total of 13 items, explaining 36,5% of the variance.

Results

To assess the incidence of mobbing, we used the Cisneros Inventory. According to Piñuel y Zavala (2004), who, from an operative viewpoint, adopted an affirmative answer as criterion to divide the sample between those who have suffered one or more mobbing behaviors (n=138) and those who have not (n=12). 138 people responded they had been the recipient of one or more of the 43 behaviors of the Cisneros inventory over the period of six months at the surveyed company.

As a result of the survey, we noticed that most of the mobbing behaviors appear with a frequency of at least 30% and the median is once a week. In regard to frequency percentages, the main mobbing behaviors that are noteworthy are: 'They prohibit my companions or colleagues to speak with me" (37.3%), "They underestimate me and ruin my work, no matter what I do" (36.7%), "I receive illegal pressure to work faster" (36.0%), "They assign me unreal implementation times or out- of- proportion workloads" (36.7%), "They invent and spread rumors and calumnies about me in a hostile way" (35.3%), "They accuse me unwarrantedly of diffuse breaches, errors and failures" (35.3%). In general, the most frequent hostile behaviors were related to work performance.

Also, of the total surveyed, 145 answered that the main source of mobbing was horizontal, coming from their fellow workers, and only 3 mentioned that the source was vertical, coming from their head supervisors.

Regarding the relation of the subscales of mobbing, results in table 4 show a positive and statistically significant association, where Spearman correlations are : E1 vs. E2 S = 0.886, E2 vs. E3 = 0.863, E3 vs. E4 = 0.97, E4 vs. E5 = 0.94.

As shown in table 4, Alpha Cronbach coefficients are higher than 0.70. A Pareto behavior was observed in the descriptive statistic of each subscale; where the 20% of each subscale displays the greater score, and 80% do not display it. According to this, we found results that showed that 22.7% (34) of the surveyed employees suffered a high level of personal humiliation, whereas 77.3% (116) did not, as shown in table 5.

In regard to the rest of the subscales of the model, the results of the surveyed employees showed that 24.7% (37) of the surveyed employees had a high level of professional downgrading; whereas 75.3% (113) did not.

About Exposure to Risks related to the task, table 6 shows results where 23.3% (35) of the employees presented a high level of exposure, whereas 76.7% (115) did not.

Also, table 7 shows results where 28.7 % (43) of the surveyed employees suffered a high level of the ignoring subscale; while 71.3% (107) did not.

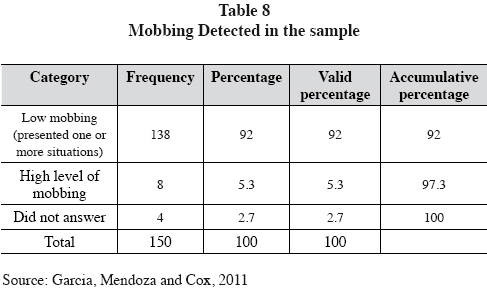

Finally, for Mobbing detected in the sample, as shown in table 8, 5.3% (8) of the surveyed employees showed a high level of mobbing while 94.7% (142) did not.

Even though a high number (138) of employees reported to have suffered at least one of the 43 behaviors of the Cisneros inventory, only 5.3% are experiencing the mobbing behavior in a high level at the surveyed organization.

Discussion

As shown in this research, even though only 8 of the surveyed employees (5.3%) suffered a high level of mobbing, 138 of the surveyed employees reported having suffered one or more of the bullying behaviors during a continuous six month period. Also, at least 30% of the surveyed employees reported they had been the recipient of one or more of the behaviors at least once a week. In Mexico's maquila industry, personal work conditions can perhaps be harsh. Collectively, employees are mostly young and with low scholarship levels. Further, the predominant company culture tends to be highly hierarchical and with a prevailing male value system. According to Hofstede, (2010) Mexico scores 69 on the masculinity dimension and is thus a masculine society. In masculine countries, the emphasis is on competition and performance and conflicts are resolved by "fighting them out". These conditions do not augur well for the reduction of the mobbing behavior in the maquila industry in Mexico. Most employees are in a vulnerable position where abusive and hostile behaviors are easily performed without penalty. Thus, managerial reaction, or lack thereof, leads itself to an atmosphere and culture that are conducive to an escalation of mobbing and mobbing-related behaviors.

One of the most insidious common characteristics of mobbing is that it usually does not leave visible signs. The psychological deterioration observed in the victims can quite easily be attributed to personal problems or relations with their fellow workers. Generally this type of mobbing behavior is shown where the group head harasses the subordinate (vertical descendent mobbing behavior), but in the surveyed organization we observed that the majority of cases were when the harasser and the victim have similar positions (horizontal mobbing).

Scarce research has been done in Mexico on the subject of mobbing in terms of determining its proportions and its real scope. Mobbing is a serious organizational pathology, but in order to take timely action inside an organization before it causes irreparable damage, it must be well-researched and well-known.

The different forms of mobbing used by predators to intimidate their victims such as assigning meaningless tasks or being ignored, are also mentioned in different research done (Einarsen and Rakness, 1997; Vartia, 2001; Zapf et al., 1996) as main behaviors of bullying.

Summing up, our present findings show that the mobbing problem can and should be considered within the framework of prevention of workplace risks. Whether or not the workers have self-labeled themselves as mobbing victims, its incidence in the workplace, mobbing must be recognized as a phenomenon that affects workers' health; thus, the quality and longevity of their service. By applying preventive policies to this phenomenon, especially to work-related bullying behaviors and personal attacks, the emergence of the predators will be reduced.

This research findings are similar to García and Cox (2007) who estimated that 65% of problems related to unsuccessfulness at work are not the result of lower work capabilities or motivation, but of strained interpersonal relationships. Also Leymann and Gustafsson (1996) found in their research similar results, where horizontal mobbing was the consequence of a closed circle in which a competent employee, because of its capabilities, provokes envy among fellow workers, and in case of a negative reaction to harassment reinforces the mobber in his/her actions.

Regarding the limitations of this study, other sources of information, in order to compare and contrast this organization data, were not available. It would be enlightening, for example, to compare incidents of bullying or fighting in the workplace, rates of absenteeism due to bullying, conflict and organizational climate, and other mobbing-related behaviors in maquila centers versus other domestic industry.

Another limitation is the lack of measuring instruments specifically developed and validated to the Mexican language and population. As those who have done questionnaire-based research across languages will attest, there are terms, words, phrases, and sayings that do not translate well from one language to another. Thus, an instrument that is validated in its "native" language may not be as valid in another language. In this research, using a Spanish instrument, even when adapted, some words and expressions are difficult to understand and some expressions have no meaning in the Mexican context.

Research should be done using a larger sample and developing or adapting research instruments to take into consideration the particular aspects of the Mexican language and of Mexican culture. In addition, great opportunities exist to investigate how burnout and mobbing relate to each other; i.e., questions of whether mobbing conditions lead to burnout and whether burnout conditions lead to mobbing should be analyzed within the context of the Mexican culture. Within a larger global context, many of the above questions should be investigated between and among other languages.

Conclusions

In this paper, we analyzed research showing that mobbing at the workplace is a common practice in today's organizations and that horizontal workplace mobbing is the most prevalent form at the maquila facilities of northern Mexico. Hence, workplace mobbing is worrying, also because it is a non-rational organizational behavior and represents an abuse to employees that suffer as victims of these behaviors for years. We also showed that causes of and facilitating circumstances for workplace mobbing, mentioned by previous research, match current organizational conditions (Zadarska, 2009; Mc Kenna, 1995; Paoli, 2000; Bruce et al., 2005; Isaksen et al. 2007). This paper highlighted that it is not the organizational conditions themselves that are to "blame", but an inadequate transformation of leadership and power in reaction to those conditions. Using the Cisneros'scale we were able to identify the most common behaviors that lead to workplace mobbing beyond the organization. It seems that in the surveyed company, supervisors have no clue of their true work as servant leaders to guide and help the employees in the production lines to optimize their resources and avoid and prevent bullying/mobbing at the work place. In this organization, workplace mobbing is a pathology of the current conditions, resulting from not acting out the full ethical potential of the discourse of excellence, adventure, creativity and responsibility that the company preaches.

Management audits as well as policies towards workplace mobbing should bear attention for this. Future research obviously has a task here. The rules of right which go along the new power/knowledge bond should be finely tuned as to their organizational implications. This will entail a search for best practices of institutionalizing empowerment and autonomy in organizations.

References

Adams, A. (1992). Bullying at Work. How to Confront and Overcome It. London: Virago. [ Links ]

Agervold, M. (2007). Bullying at work: a discussion of definitions and prevalence, based on an empirical study. Scandanavian Journal of Psychology 48 (2): 161-172. [ Links ]

Ashforth, B. (1994). Petty Tyranny in organizations. Human Relations 47 (7): 755-778. [ Links ]

Baron, R. et al. (1999). Social and Personal Determinants of Workplace Aggression: Evidence for the impact of Perceived Injustice and the type A Behavior Pattern. Aggressive Behavior (25): 281-296. [ Links ]

Bassman, E. (1992). Abuse in the Workplace. New York: Quorum. [ Links ]

Brodsky, C. (1976). The Harassed Worker. Toronto: Lexington Books, DC Heath & Company. [ Links ]

Bruce, S. M., H. M. Conaglen and J. V. Conaglen (2005). Burnout in physicians: a case for peer-support. Intern Med J 35 (5): 272-278. [ Links ]

Crawford, N. (1999). Conundrums and confusion in organisations: the etymology of the work 'bully'. International Journal of Manpower 20 (1/2): 86-93. [ Links ]

Einärsen, S. (1998). Dealing with workplace bullying: the Norwegian Lesson, Paper presented at the Bullying at work 1998 research Update Conference. Staffordshire University Business School, 1 July. [ Links ]

----------, (2000). Harassment and Bullying at Work. A Review of the Scandinavian Approach, Aggression and Violent Behavior 5 (4): 379-401. [ Links ]

----------, B. Raknes and S. Mattiensen (1994). Bullying and harassment at work and their relationship to work environment quality: an exploratory study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 4 (4): 381-401. [ Links ]

----------, M. Aasland and A. Skogstad (2007). Destructive Leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. The Leadership Quarterly 18 (3): 207-216. [ Links ]

Fidalgo, M. and I. Piñuel (2004). La escala Cisneros como herramienta de valoración del mobbing. Psicothema 16 (4): 615-624. [ Links ]

Fox, S. and P. E. Spector (2005). Counterproductive work behaviour. Washington: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Garcia, B. and J. Cox (2007) Management and Development of a Workforce: The Challenge of sustainability. Revista Investigación Administrativa 100. [ Links ]

Glasl, F. (1994). Konfliktmanagement. Ein Handbuch fur Fuhrungskrafte und Berater. (Conflct management: A handbook for managers and consultants, 4th edition). Bern, Switzerlan: Haupt. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G., G. J. Hofstede and M. Minkov (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Isaksen, S. and G. Ekvall (2007). Assessing the context for change: A technical manual for the Situational Outlook Questionnaire. NY: The Creative Problem Solving Group. [ Links ]

Lee, D. (2000). An analysis of workplace bullying in the UK. Personnel Review 29 (5): 93-610. [ Links ]

Leymann, H. (1997). The Mobbing Encyclopaedia. Disponible en http://www.leymann.se [ Links ]

----------, and A. Gustafsson (1996a). How ill does one become of victimization at work? Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 1996 (5): 61-77. [ Links ]

----------, and A. Gustafsson (1996b). Mobbing at work and the development of post-traumatic stress disorders. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 5. [ Links ]

Liefooghe, A. (2003). Employees Accounts of bullying at work. International Journal of Management and Decision Making 4 (1): 24-34. [ Links ]

----------, and D. MacKenzie (2001). Accounts of Workplace Bullying: The Role of the Organization. The European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 10 (4): 375-392. [ Links ]

Lima, M., A. Guerreiro, M. Lino, M. Luna, C. Yela and A. Antón (2003). Acoso psicológico en el trabajo, Unión Sindical de Madrid, Región CC-OO. Cuadernos Sindicales, Ediciones GPS, Madrid. [ Links ]

Meliá, J. L. (2006). The Best Psychosocial Correlates of Mobbing (bullying) at Work. In P. Mondelo, M. Mattila, W. Karwowski and A. Hale (eds.). Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Occupational Risk Prevention. [ Links ]

McCarthy, P. (1996). When the mask slips: inappropriate coercion in organizations undergoing restructuring. In P. McCarty, M. Sheehan and W. Wikie (eds.). Bullying: From Backyard to Boardroom. Alexandria: Millennium Books. [ Links ]

McKenna, S. (1995) The business impact of management attitudes towards dealing with conflict: a cross-cultural assessment. Journal of Managerial Psychology 7 (10): 22-27. [ Links ]

Niedl, K. (1995). Mobbing/ bullying at the work place. München: Rainer Hampp Verlag. [ Links ]

Paoli, P. and D. Merllie (2000). Third European survey on working conditions. Dublin: European Foundation for the improvement of living and working conditiona. [ Links ]

Piñuel, I. (2004). Informe Cisneros V, la incidencia del mobbing o acoso psicológico en el trabajo en la administración. [ Links ]

----------, and I. Savala (2001). Mobbing: cómo sobrevivir al acoso psicológico en el trabajo. Bilbao: Sal Terrae. [ Links ]

Rayner, C. (1999). Bullying at work. PhD Thesis, Dept of Management Science, University of Manchester, United Kingdom. [ Links ]

----------, and G. Cooper, G. (2006). Workplace Bullying. In E. K. Kelloway, J. Barling and J. J. Hurrell, Jr. (eds.). Handbook of Workplace Violence. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 47-89. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, C., S. Escartín, G. Porrúa and P. Martín (2008). Un análisis psicosocial del mobbing y de sus comportamientos abusivos. Revista D'estudis de la violência (5): 1-23. [ Links ]

Sheehan, M. (1996). Case Studies in Organizational Restructuring. In P. McCarty, M. Sheehan and W. Wikie (eds.) Bullying: From Backyard to Boardroom. Alexandria: Millennium Books. [ Links ]

Thylefors, I. (1987). Syndabockar: om utstotning och mobbning i arbetslivet (About expulsion and bullying in working life). Stockholm: Natur och Kultur [ Links ]

Topa, G. y J. Morales (2007). Identificación organizacional y ruptura de contrato psicológico: sus influencias sobre la satisfacción de los empleados. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy (7): 365-379. [ Links ]

Vartia, M. (2001). Consequences of workplace bullying with respect of the well-being of its targets and the observers of bullying. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment Health 27 (1): 63-69. [ Links ]

Van Der Vegt, G., B. Emans. and E. Van De Vliert (2000). Team members' affective responses to patterns of intragroup interdependence and job complexity. Journal of Management (26): 633-655. [ Links ]

Von Bergen, C.W., J. A. Zavaletta Jr and B. Soper, B. (2006). Legal Remedies for Workplace Bullying: Grabbing the Bully by the Horns. Employee Relations Law Journal (32): 14-40. [ Links ]

Wright, L. and M. Smye (1997). Corporate Abuse: How "Lean and Mean" Robs People and Profit. New York: Simon and Schuster. [ Links ]

Yildiz, S. (2007). A 'new' problem in the workplace: Psychological abuse (bullying). Journal of Academic Studies (34): 113-128. [ Links ]

Zadarska borba protiv zlostavljanja na radu. Available at http://www.h-alter.org/vijesti/ljudska-prava/zadarska-borba-protiv-zlostavljanja-na-radu. [ Links ]