Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Norteamérica

On-line version ISSN 2448-7228Print version ISSN 1870-3550

Norteamérica vol.4 n.2 Ciudad de México Jul./Dec. 2009

Ensayos

The Geographic and Demographic Challenges To the Regional Institutionalization Of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley

Los desafíos geográficos y democráticos de la institucionalización regional del Valle Bajo del Río Grande de Texas

Baltazar Arispe y Acevedo, Jr.*

*Professor of educational administration and research, College of Education, University of Texas, bacevedo1@utpa.edu.

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to examine the institutionalization of a region of the United States of America: the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley. It will use and build on theories of regional institutionalization, geography, and demography by Paasi, Harvey, Gilbert, and other theorists. This research asks how history, geography, and demography challenge the present and future regional institutionalization of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley. To answer this question, recent case studies on institutionalization and regional development in Canadian and U.S.–Mexican regions will be used to explain phenomena.

Key words: institutionalization, geography, demography, Texas, Mexico.

Resumen

El propósito del presente documento es analizar la institucionalización de una región de Estados Unidos: el Valle Bajo del Río Grande de Texas. Para ello aplicaré teorías sobre institucionalización regional, geografía y demografía de Paasi, Harvey, Gilbert y otros teóricos. En esta investigación indagaré cómo la historia, la geografía y la demografía enfrentan desde hoy y hacia el futuro la institucionalización regional de ese sitio. Para responder este interrogante y explicar el fenómeno se tomarán en cuenta estudios de caso sobre la institucionalización y el desarrollo regional en Canadá y en regiones de influencia conjunta para Estados Unidos y México.

Palabras clave: institucionalización, geografía, demografía, Texas, México.

INTRODUCTION

Harvey (2006), Hamin and Marcucci (2008), and Gilbert (1988) previously applied the theoretical frameworks of Paasi (1986; 1991) to generate and amend theories about both regional institutionalization and sustainable development. Paasi defined regional institutionalization as follows:

A socio–spatial process in which a territorial unit emerges as part of the spatial structure of the society concerned, becomes established and identified in various spheres of social action and consciousness, and may eventually vanish or deinstitutionalize in regional transformation. The process is a manifestation of the goals established by local or nonlocal actors and the decisions made by them. After being institutionalized, a region is perpetually reproduced in various social practices, that is, in the spheres of economics, politics, legislation, administration, and culture. The origin of these practices is not inevitably located in the spatial unit or in a period of time in question, but can occur on other spatial and historical scale–typically at the international or national level. We do not usually see the stages of the socialization process, because it usually takes much longer than one lifetime and can be understood only through abstractions. The region in question can vary in size. Villages, counties or provinces can emerge or disappear… Regional transformation is continually taking place on various scales and time spans. (1991: 244–245).

The article has four sections: a) A historical overview of the Texas Lower Rio Grande will set the context; b) The theoretical frameworks are used to analyze the targeted region's institutionalization; c) Next, a select number of geographic and demographic–based issues are analyzed using current socio–economic data about this region; and d) Finally, concluding observations and recommendations are offered to guide an understanding of the processes involved in regional institutionalization and propose further study.

HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHIC CONTEXT

Harvey's proposition that "regional identities are products of history" provides a historical context for linking this region's past to its present and future institutionalization (2006: 79). The Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley is a nexus that both connects and defines the rich history and geography of a territory that, once part of Mexico, was lost during the 1836 Texas Revolution and finally ceded to the United States by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 (Montejano, 1987; Saldívar, 2006; Vargas, 1999). It was in this region that the initial military clashes between Americans and Mexicans led to the Mexican War, and it was here that the last battle of the American Civil War took place (Tucker, 2001). These crucial historical events occurred in what are today Brownsville, Texas and Matamoros, Mexico and along the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo to present day Rio Grande, Texas. If anything, one could surmise that this region's existence, as a part of the United States, may be an aberration to the theory of "Manifest Destiny" that guided U.S. expansionist and military policies during the nineteenth century as noted by Opie (1998: 1).

There are very strong historical roots to how the region's predominately Mexican–American population defines itself in relation to the rest of Texas, the United States and Mexico. Its regional history is grounded in shifting geographic boundaries, warfare, colonization, and the continuing search for an identity of a people who appear to be in continuous transition on the border. The Rio Grande Valley (figure 1) is situated at the southeastern–most point of the border between Mexico and the United States, and it is here that theory and data will be used to describe a region in transition. This region's institutionalization is impacted by its geographic location and by a burgeoning demography and in many instances political and economic policies and events that begin in the far–away capitals of Mexico City's Federal District, and Washington, D.C.

According to Miller,

the border has come to represent many things to many people, yet it remains the most misunderstood region of North America. Our southern frontier is not simply American on one side and Mexican on the other. It is a third country with its own identity. This third country is a strip two thousand miles long and no more than twenty miles wide. It obeys it own laws and has its own outlaws, its own police officers and its own policy makers. Its food, its language, its music are its own. Even its economic development is unique. It is a colony unto itself, long and narrow, ruled by two faraway powers. (1981: XII)

The line of demarcation between the two nations was stretched to 60 kilometers north and south of the U.S/Mexico border by the La Paz Agreement of 1987 by Presidents De la Madrid of Mexico and Reagan of the United States (EPA, 2002). It is within this strip of land that Americans of Mexican descent are expanding demographically and this growth presents many challenges and opportunities for sustainable development. The borderline, between the Rio Grande Valley and northern Mexico, is the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo. Kay refers to this boundary as "a wide, sluggish river, of no great natural beauty or interest. But because it forms the border between the United States and Mexico for a thousand miles, it has great political, social and economic significance" (2004: 25).

SETTING THE THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The challenge to academic researchers is to identify, analyze, and apply theoretical constructs to guide research as they attempt to discover and explain dynamic social phenomena. Miles and Huberman believe that a "conceptual framework" must guide all research and that this "explains, either graphically or in a narrative form, the main things to be studied –the key factors, concepts, or variables– and the presumed relationships among them" (1994: 18). Maxwell also believes that a researcher must have a "conceptual context" to guide a study and he defines it as "a system of concepts, expectations, beliefs and theories that support and inform your research" (1996: 25–26). He also provides the following guidance: "The most important thing to understand about your conceptual context is that is a formulation of what you think is going on with the phenomena you are studying –a tentative theory of what is happening and why." He points to several essential elements for constructing the conceptual framework: 1) your own experiential knowledge; 2) existing theory and research; 3) pilot and exploratory research; and 4) thought experiments. The conceptual framework for this paper is guided by the first three elements.

A major tenet to Paasi's theory of regional institutionalization is that no region is ever fully institutionalized and the process is continuous and always in flux. To Harvey, the institutionalization of regional spaces also appears "as a process in constant evolution over time involving different social actors" (2006: 79). It is imperative to determine how the institutionalization of the Rio Grande Valley is occurring by drawing from theories, specifically Harvey's (2006) application to Canadian regions. By doing so, current and emerging challenges may be identified and used to determine if there are indeed threats or opportunities for this region to maintain its sustainability.

Paasi's theory provided four evident stages, which may or may not be sequential, of an institutionalized region (1986: 105–146; 1991: 229–256). Hamin and Marcucci provide this succinct summary of Paasi's theoretical construct:

Stage one, construction of territorial shape: Here the essential elements consist of those functional processes through which actors define boundaries for the region and develop expectations of appropriate social practices within the region, such that the region becomes identified as a separate spatial sphere. A critical consideration here is the power relations among the different agents or constituencies acting within and outside of the region.

Stage two, formation of the symbolic shape: In this stage the region's name emerges and certain symbols become evident that will guide its continued identity. These symbols are important since they serve to link the region's image with a broader social consciousness of its existence and development of inhabitants' identification with the collective practices of the region (a circular process). This process establishes the region as a socio–cultural unit.

Stage three, emergence of institutions: Activists, elites and mass media engage in establishment of both formal institutions and local or non–local practices in the spheres of politics, economics, legislation and administration. Taken as a whole, this is the development of a regional culture with implicit socialization of individuals into the region community and production of social consciousness.

Stage four, establishment of a region: To Paasi, this is a continuation of the institutionalization process, after the region has an established status structure and social consciousness of the society, whether through formal administrative institutions or local practices. At this point the region is ready for wider acknowledgement and potentially place marketing. There may be an ongoing struggle over resources and power. (2008: 469).

This author suggests that Paasi's theoretical framework be adjusted so that other constructs may be considered and evaluated within the context of how other theorists see regional development and institutionalization in the geographic context of what is referred to as "Third Space."

THE THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF "THIRD SPACE" AND REGIONAL INSTITUTIONALIZATION

Gilbert proposed that in order to understand a region's development and identity, it is necessary to conduct an analysis "that involves selection and in–depth investigation of the particular aspects of social relations in space…namely the structure of economic production of labor and capital, the cultural patterns and political relations" (1988: 218). He also stated that in studying a region, no one single order of phenomena should be used as a guide. Rather, he is unequivocal in proposing that "cultural, political and economic processes together shape and structure the specific regions under investigation and it is only through the study of their relationship that regional specificity can be retraced" (1988: 219). Additionally, he proposed that "a regional synthesis should then allow an interpretation of the region as a product of the interconnectedness of different scales" (1988: 219).

In considering Paasi (1991) and Gilbert (1988), Harvey proposes that "the institutionalization of regional space appears, then, as a process in constant evolution over time involving different social actors" (2006: 79). A review of Paasi, Gilbert, and Harvey reveals a recurring theme: "space" or a sense of place is an important consideration in the institutionalization process. Space/place is the geography: the region or the setting where social action takes place by all actors.

Both Gutiérrez (1999) and Soja (2000) refer to the place where social action takes place as "Third Space" or a setting where a people moves and interacts within an environment. While Soja's constructs are grounded in the urban area of Los Angeles, I propose that they can be applied to the current analysis. Of note is Soja's principle:

I use the concept of Third space most broadly to highlight what I consider to be the most interesting new ways of thinking about space and social spatiality, and go about it in great detail, but also with some attendant caution, to explain why I have chosen to do so. In its broadest sense, Third space is a purposefully tentative and flexible term that attempts to capture what is actually a constantly shifting and changing milieu of ideas, events, appearances, and meanings. If you would like to invent a different term to capture what I am trying to convey, go ahead and do so. (1996: 2)

Soja's guidance is that one must be certain to consider space, history, and social dimensions in the analysis of regions. Gutiérrez believes that the formerly Mexican citizens, who became American through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, came to occupy a "Third Space" in the borderland area (1999: 481–517). The space that Rebert (2001: 1–3) describes as the "Línea" is the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo that created the border. In his narrative about revolutionaries on the Texas–Mexico border in the early twentieth century, Young claims that "throughout the nineteenth century, but especially after mid–century, the inhabitants experienced the borderlands as a relatively coherent in–between region, a third space in many ways separate from Mexico and the United States" (2004: 7–11).

Arreola also makes a case for space as a critical variable in the analysis of regions when he states that

the idea of landscape as a political visual concept and scholarly subject has been assessed and reviewed by geographers. That landscape can have multiple meanings to different groups as well as individuals has been explored, and several geographers have articulated systematically how landscape can be read, providing insight into place and social situations. Most cultural geographers accept the fact that landscapes are socially constructed….Landscape can be a signifying framework through which a social system is communicated, reproduced, experienced and explored. (2002: 4–5).

These, then, are the essential elements that will be addressed as the four constructs of Paasi's theory, and other theorists are used to conduct what may be considered a benchmark analysis of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley as a viable and continuously institutionalized region.

STATUS OF THE RIO GRANDE VALLEY’S REGIONAL INSTITUTIONALIZATION

PAASI’S STAGE ONE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF TERRITORIAL SHAPE

A historical analysis by Arreola (2002: 1–5) leads to an assertion that this region's geographic boundaries were defined by Spaniards in the sixteenth century and by Native Americans long before the coming of Europeans. The same author also proposed that "this was the land over which several Spanish entradas or overland explorations marched across the Rio Grande and South Texas during the late 17th century" (2002: 11). Furthermore, he stated that "Texans, according to one distinguished geographer, are said to maintain a 'perpetual image' of South Texas as a directional region, and at least one prominent Mexican American historian has labeled the region between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande the 'Tejano cultural zone'" (2002: 10). According to Montejano (1987: 31), Fredrick Law Olmsted, the New York Times reporter, referred to the newly acquired territory as the "Mexican border frontier."

Arreola also cites an observation by Olmsted about the Rio Grande borderlands which he described as "a region so sterile and valueless, as to be commonly reputed a desert, and being incapable of settlement, serves as a barrier –separating the nationalities, and protecting from encroachment, at least temporarily, the retreating race" (Arreola, 2002: 13). The Rio Grande Valley has become identified, as Paasi put it, as "a distinct unit in the spatial structure" (1991: 244).

PAASI’S STAGE TWO: FORMATION OF THE SYMBOLIC SHAPE

Both Paasi (1991) and Harvey (2006) claim that the formation of symbolic shape is essential for the development and establishment of social structures that are the territorial symbols for the region. Paasi proposed that "one essential symbol is the name of the region, which connects its image with the regional consciousness….Territorial symbols are often abstract expressions of group solidarity embodying the actions of political, economic, and cultural institutions in the continual reproduction and legitimization of the system of practices that characterize the territorial unit concerned" (1991: 245).

Harvey (2006) applied Paasi's and Gilbert's theoretical constructs to his analysis of a select number of Canadian regions. From his analysis, Harvey concluded that "these regional identities are products of history and are not therefore the simple equivalents of territorial boundaries arising from administrative division of a given territory. Several economic, social, and cultural factors contributed to the structuring of Canada's regions" (2006: 79). In considering Harvey, some elements can be applied to the regional identity of the Rio Grande Valley and its symbolic shape.

This autor proposes that the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo, because of its location, has impacted the historical, political, economic, and social/cultural experience of people both south and north of it and is the umbilical cord to the assumption of territorial shape for the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley. According to Metz, "the Spanish explorers originally believed that the Rio Grande was different streams. They called it the Rio Grande (Great, or Big, River), Rio de las Palmas (River of Palms –as seen from the Gulf) and Rio Bravo del Norte (Bold, or Wild, River of the North). In Mexico it is still called the Rio Bravo" (1989: 293). To Paasi, the name of a region is an essential symbol, "which connects its image with regional consciousness" (1991: 245).

There is one distinction, however, that must be made about how the Rio Grande Valley and the regions of Canada emerged as geographic designations within their individual nations. As previously noted by Harvey (2006: 79), the designation of the Canadian regions was more a function of administrative division. That was not the case with the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley; this region is a by–product of war, conquest, and international treaty. The Rio Grande Valley was at the center of the debate between the Republic of Texas and Mexico from the moment it was separated from Mexico as a result of the 1836 Texas Revolution. According to Suárez–Mier (2007), when Texas decided to become a part of the United States in 1845, it added kindling to ignite the Mexican War. The outcome of this war, the defeat of Mexico by the United States, led to the loss of the northwestern Mexican territories through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848 and the Gadsden Purchase of 1853. These actions, contends Suárez–Mier (2007: 17–18), were either a "land grab or Manifest Destiny" by the United States.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo also created the U.S. and Mexican Boundary Commission that was charged with drawing the boundary line to separate Mexico from the United States. Rebert concluded that "the treaty followed the Rio Grande, the 'Great River,' known in Mexico as the Rio Bravo (Great or Wild River). It was implemented as the boundary as a matter of political necessity, since a U.S. claim to the Rio Grande as the boundary of Texas had been a precipitating cause to the U.S.Mexican War" (2001: 3).

Suárez–Mier is emphatic in his observation that "there is not a clear understanding in the U.S. of just how painful that history remains for Mexico" (2007: 18). As previously noted, the Rio Grande Valley has its geographic anchor at the mouth of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo, and its name is used for this river, at least on the United States side of the border.

I suggest that Harvey's proposition "that economic, social, and cultural factors contributed to the structuring of Canada's regions" can also be applied to the structure of the Rio Grande Valley (2006: 79). While it has been shown that war and international treaties created the border between Mexico and the United States, this region also demonstrates a continued interwoven relationship with the northern Mexican states of Tamaulipas and Nuevo Leon. Prior to the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Alba assessed this border–driven relationship as follows:

The border region of northern Mexico and the role it plays could be classified as being a unique situation, not to be attributed only to the its being part of Mexico, a country of relatively little and belated industrialization, and bordering on the United States, a heavily industrialized country, which is in the process of becoming post–industrial. This unique situation stems first and foremost from the fact that this Border area is a point of convergence of an intense relationship and that it shares many interests with its northern neighbor although the two countries, surprisingly, seem to have little in common. (1984: 21).

It is now necessary to reiterate Harvey's position that "regional identities are products of history" (2006: 79). What has transpired since Alba's 1984 observations, a brief period of less than 30 years, has to be reviewed and assessed. During this time, NAFTA was enacted in 1993, immigration has become a more intense front–burner issue, the 9/11 terrorist attacks have caused the merger of immigration policy with border security, and there is an ongoing and scattered debate and on–and–off attempts to construct a border wall/fence. Recent benchmarking and demographic studies of south Texas by Soden (2006), Sharp (1998), Murdock et al. (1997), Gibson and Rhi–Perez (2003), and Acevedo, Rodriguez, and De los Reyes (2003) provide data that show that the four counties of the Rio Grande Valley have come to comprise the poorest region in the United States. This region falls within the geographic parameters of south Texas, which both Sharp (1998) and Soden (2006) believe is so economically depressed that if it were the fifty–first state of the United States of America, it would rank last in all socio–economic indicators.

Alba's claim (1984) that the two northern neighbors have little in common is one that must be reconsidered. Historically, the communities on both sides of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo have come to resemble Siamese twins. What is evident is that the regional institutionalization of concern here is not solely a north side of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo event but a bi–national experience. This is also an observation made by Suárez–Mier when he states,

For all the differences between Mexico and the United States, the border region forms an unbreakable bond between two countries. The communities that lie along and frequently straddle it enjoy a unique symbiosis that impels them to work together to address common problems: legal and illicit trade, pollution and management of water resources, crossings of people who work on one side but live on the other side and endless other exchanges that make them far more attached to each other than with other towns in their own countries. (2007: 17)

Kearney and Knopp (1995: 71–95) propose that the conditions for duality of life on the border were an outcome of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. They also believe that the loss by communities on the southern side of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo of their land on the north side of the river resulted in a bond with the new American communities north of the border. These Rio Grande Valley communities include Brownsville, Rio Grande City, McAllen, Pharr, Harlingen, Hidalgo, and Roma.

The evolution and development of the borderlands is the result of the significant role of border communities that Kearney and Knopp refer to as "Twin Cities" or "Border Cuates" (1995: 1). According to these authors,

The border towns, while long isolated from and unsung by the main societies of the two respective countries, have played a significant role in the destinies of their two nations and seem destined to play an even larger role in the future. Their local interactions exert an impact in the larger relations between the two parent countries….The cliché that the border towns have been mere victims of national policies is inaccurate. At times, they have exerted an impact on the fate of the entire continent. Local influence was at work in the creation of the United States–Mexico border. Activities in these towns helped to catalyze the Mexican–American war. Border town developments also played a role in the entry of the United States into World War I. Most recently, local problems have helped to draw national governments into such experiments as the bracero program, Pronaf, the maquiladora program and now the free trade zone talks. (1995: 3)

The significance of the relationship between Brownsville and Matamoros is also observed by Zavaleta when he states, "The history of the Brownsville–Matamoros border community brings to life the fullest meaning of the concept of symbiosis. In the biological sense, the term describes the mutual interdependence of two organisms. However, when applied to border towns the concept implies the idea of interrelated cultures, economies and societies" (1986: 125).

Another critical element of cross–border relations also observed by Kearney and Knopp was the advent of the maquiladora industry (twin plants with production on the Mexican side and supply on the United States side of the border) in 1965 (1995: 239–265). The impact on transnational economies is also the focus of research by Gilmer and Cañas in their report for the Federal Reserve Bankof Dallas. They cite the economic significance of these industries through their observation that "there is strong economic interaction between border city pairs, apparent from a count of auto, truck, and pedestrian traffic crossing the bridges that connect them, from the number of Mexican license plates on autos parked in U.S. malls, or the many service and good suppliers in the U.S. border cities that support manufacturing located in Mexico" (Gilmer and Cañas, 2005: 3).

What is evident is that the institutionalization of the Rio Grande Valley is affected by both its proximity and historical bond with Mexico's northern communities straddling the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo. In his study of the regions of Quebec, Harvey contended that "now more than ever, individuals need to connect to their area and to develop a sense of place" (2006: 91). The research confirms both Harvey's (2006) and Paasi's (1991) theoretical constructs that history and a combination of economic, social, and cultural factors contribute to the structuring of regions.

PAASI’S STAGE THREE: THE EMERGENCE OF INSTITUTIONS

The formalization of regional governance by the Texas legislature during the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries has created a region that essentially replicated the governmental structure of the balance of the state. What is significant for the assertion of political, administrative, and bureaucratic structure is the dominance of the Mexican American in regional elected government positions throughout the Rio Grande Valley.

The rise of what may be called the modern equivalent of Political Action Committees (PACs) such as the politically moderate League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) in 1929, and the G.I. Forum in the 1950s, eventually led to the evolution of the slightly more radical Chicano Movement in the 1960s. Collectively, these political organizations were a hybrid of non–government agencies (NGOs) and community–based organizations (CBOs). This expanded participation is best known for adding more voters to registration rosters through the efforts of the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project (SVREP) and expanding the number of Mexican Americans elected to political office in the Rio Grande Valley and south Texas (Arreola, 2002; Montejano, 1987; Velázquez, 2007). The Valley Partnership (2008) provides data that show that Mexican Americans have significant roles at all levels of governance. Six of the seven members of Congress for south Texas are Mexican American. Seven members of the Texas state legislature, 30 of the 43 mayors, and 90 percent of school board members in this region are Mexican Americans. This active participation in both government and political offices confirms Paasi's theoretical proposition that "power relations manifested in political, administrative or bureaucratic, economic practices play a crucial role in the emergence of territorial shape –the very term territory carries a connotation of geographical space and power" (1986: 245).

The development of institutions is another affirmation of institutionalization evident in the Rio Grande Valley. According to Paasi (1986), two such institutions are those affiliated with educational development and with mass media. Essential to the Rio Grande Valley's identity are the institutions of higher education that contribute to the region's intellectual and knowledge capital. Sharp (1998) provides a summary of the legal challenges initiated by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund (MALDEF) to correct the inequities in South Texas higher education. The outcome of these cases was the expansion of higher education institutions in south Texas. They led to the adoption of the South Texas/Border Initiative in 1989 that resulted in the establishment of regional campuses for the University of Texas in Edinburg and Brownsville, Texas. Another outcome was the creation of Texas A&M University campuses in Corpus Christi and Laredo along with the founding of South Texas College in 1993. These post–secondary educational institutions are recognized as critical components of the region's economic development and the lead drivers for the social and cultural life of their constituencies.

Paasi also subscribed to the importance of newspapers, observing that "the mass media of the regions and especially the newspapers, which bear strong economic ties with market areas, are normally significant for regional consciousness" (1986: 129). Deeken (2006) claims that television is the major media of influence of this region's predominately bilingual population. There are eight Spanish language television stations either in the Rio Grande Valley or in proximity in northern Mexico. There are also three daily newspapers in this region and two, which have Spanish–language supplements. The data shows that the Rio Grande Valley has established the institutions that Paasi (1991) presented as necessary to the development and reproduction of regional consciousness and essential for regional institutionalization.

PAASI’S STAGE FOUR: THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A REGION

The review of Paasi's three stages, critical to institutionalization, leads one to state unequivocally that the region known as the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley has been established. It is situated within a separate spatial sphere; it has the pre–requisite identity, through its name, and the corresponding symbols that anchor the residents' identification; it has been established as a socio–cultural unit; and finally, it has the necessary governance agencies, media outlets, educational institutions, economic constructs, and social consciousness within the state of Texas.

The bi–national scope of this region's institutionalization presents unique challenges to its continued sustainability along with the domestic factors threatening its development. Gaffield's study of the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec that are separated by the Ottawa River serves as a point of reference as the bi–national institutionalization of the Rio Grande Valley is considered (1991). According to Gaffield, the separation of the two Canadian regions has created a "Janus effect" in that Ontario and Quebec have distinct metropolitan forces at play that impact and influence the residents on either side of the Ottawa River. A 1985 article in the French newspaper Le Monde cited by Gaffield provided the following description of this region as "une région entre deux mondes" (one region between two worlds) (1991: 67). Gaffield's hypothesis is that a line of demarcation, such as the Ottawa River, acts as a boundary or barrier to the identity of residents of the affected regions since they literally exist in two worlds. A similar line of demarcation is evident in the region under consideration: the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo. The significant difference is that Gaffield's focus is intra–national; the focus here is international.

Gutiérrez's observations reflect Gaffield's in that "the evidence of new forms of identity and orientation are obvious. For example, habitual transmigrants and their extended families on both sides of the border represent one case of a group that may well be operating under substantially different assumptions and expectations about their place in the nation–state" (1999: 512). Anthropologist Michael Kearney, as quoted in Gutiérrez (1999: 513), refers to this experience as "transnationalizing" the identities of people who habitually travel through the social space transformed by these trends." Foucault refers to these spaces as "heterotopoias" and described them as "the space in which we live, which draws us out of ourselves, in which the erosion of our lives, our time, and our history occurs" (as quoted in Soja, 1996: 15).

In order to present and consider the challenges to the regional institutionalization of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley in a spatial context, the following sections will address those issues within the context of the reviewed theoretical constructs and timely data.

THE GEOGRAPHIC AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES TO THE REGIONAL INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF THE TEXAS LOWER RIO GRANDE VALLEY

The theories that guide this paper are grounded in two essential elements: geography and demography, which provide the context for what has been described as regional institutionalization. These elements, though distinct, are interlinked and replete with human activity, which occurs within a landscape that generates both the space and the foundation for social interaction by the inhabitants and residents of a region. According to Gaffield, "regions are simply more discrete geographic spaces in which different social groupings can be analyzed in more detail" (1991: 65). Hargroves and Smith (2005), Harvey (2006), Saldívar (2006), Soja (1989; 1996), Sharp (1998), and Kay (2004) consider geography a critical element in sustainable development of regions and their inhabitants.

Saldívar describes a borderland such as the Rio Grande Valley as a "transnational imagery" and that it

is thus to be understood not only ideologically but also as a chronotopoe, a spatial and temporal indicator of a real contact zone that is historical and geographical, cultural and political, and discursive. The borderlands are populated by transnational persons whose lives form an experiential field within which monologically delineated notions of political, social, and cultural identity simply do not suffice. The geographical particularity and historical specificity of the border region thus mark it as category of an immediate reality. (2006: 62–63)

Hamin and Marcucci's (2008: 468) reaffirmation of Paasi's proposition that regionalization is a process, a becoming rather than an extant condition, will serve to guide the analysis of data that demonstrates that a region that is a host for human endeavors is always in a state of becoming.

The challenges presented in the geographic axis (figure 2) are by no means exhaustive and only some of the most critical ones, as perceived by this observer, will be addressed through data. These present and emerging challenges are location, environment, infrastructure, and security, along with some corresponding policy issues that have been identified as originating with the United States federal government and that affect the region.

As depicted in the model, the variables that affect the region are in a constant flow pattern and transposing themselves between the two key lynchpins: geography and demography. The data will serve to describe the reality of what is transpiring in the region and how it affects both the residents and the space they occupy.

THE GEOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES

New guidelines by the Office of Management and Budget established the parameters that define a region of the United States as either urban or rural. According to the new standards, the Rio Grande Valley is now to be classified a "Metropolitan Statistical Area." These "have at least one urbanized area of 50 000 or more population, plus adjacent territory that has a high degree of social and economic integration with the core as measured by commuting ties" (Office of Management and Budget, 2007: 1–154). Essentially this means that the Rio Grande Valley is in transition from a rural to a conglomeration of over 60 communities and cities linked to two individual metro areas (Brownsville–Harlingen and McAllen–Edinburg–Mission), each with over 150 000 inhabitants.

There is an evident contradiction in how the Rio Grande Valley is perceived in general and what it is becoming in reality. Historically, this region was lauded for its rural geography and agriculture–based economy; it still is, in many regional public relations publications (Rio Grande Valley Texas, 2008; Texas Border Business, 2009; U.S. Department of Agriculture's Agricultural Marketing Service, 2008). In his economic analysis of Rio Grande Valley for the Federal Bank of Dallas, López (2006) provided data demonstrating that agriculture contributes less than 2 percent to the economy of this region. The challenge remains how to develop and implement public policies that recognize, as López reported, that the emerging economic drivers for this region are government, including public schools and universities (27.1 percent), health care and social assistance (20 percent), as well as the retail industry (9.8 percent), which relies on the Mexican consumer to shop on the Texas side of the border. Wu and Gopinath (2008: 392–393) identified three major factors that affect economic development and which, I would propose, are critical to the regional institutionalization of the Rio Grande Valley. These factors are: 1) natural endowments (e.g., water availability, land quality, environmental amenities); 2) accumulated human and physical capital (e.g., educational level of the work force, infrastructure); and 3) economic geography (remoteness, proximity to input and output markets).

The environmental issues of concern to both the public and private sectors are transnational in scope as they threaten the very survival of communities on both sides of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo as cited by the Valley Water Summit (2005), EPA (2002), Semarnat (2008), and the Environmental Defense Fund (2003). In a report for the World Wildlife Fund, C. M. Wong, C. E. William, J. Pittock, U. Collier, and P. Schelle reported that this river is one of 10 most ecologically endangered in the world and that "a high level of water extraction for agriculture and increasing domestic use threatens the Rio Grande" (2007: 17–20). This report also refers to other critical issues that are having a negative impact on the survival of the river that gives the region it name. The challenge is the persistent pollution along the entire length of the river from the state of Colorado to the Gulf of Mexico, low water levels that are killing over 32 native fish species, and the competition for water by growing urban areas that are experiencing an annual population growth of between 2 percent and 4 percent.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2002: 1–5) and its Mexican counterpart, Semarnat, are collaborating to identify and respond with policy strategies to affect the environmental challenges and threats to the border region. These agencies, along with 14 Native American tribes and over 40 transregional and state and national agencies, have formed a coalition through the U.S.–Mexico Border 2012 Program to respond to threats to the environment on both sides of the border. The challenges that are being actively responded to include 1) the need for an adequate, clean water supply; 2) air pollution; 3) land contamination; 4) environmental health; and 5) responses to environment–threatening incidents from hazardous waste releases by border industries.

The development of the Rio Grande Valley's infrastructure presents a contradiction between policy and practice as well as some unintended outcomes. The 1996–2016 Rio Grande Valley Mobility Plan (2008) was adopted by the Hidalgo, Brownsville, and Harlingen/San Benito Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) and presented to the Texas Department of Transportation for implementation. The plan approved by the Texas Department of Transportation (2008) was allocated a combined US$277 749 000 for the construction and maintenance of 20 000 miles of roads, sewage, drainage systems, and highways in the nine counties of south Texas. According to the Texas Department of Transportation (2009), these investments were made to expand transportation infrastructure to support trade between the United States and Mexico as well as other nations within this hemisphere. Both investments and corresponding improvements were intended to support licit transportation to expand the economy of the region.

The U.S. Department of Justice's HIDTA (High Intense Drug Traffic Area) agency report of May 2007 about homeland security–related threats to the United States focused on the south Texas region, including the Rio Grande Valley. According to this report, prepared by the National Drug Intelligence Center, the data show that

the U.S.–Mexico border renders the area extremely vulnerable to drug trafficking and Homeland Security threats such as bulk cash smuggling, alien smuggling, border related violence, gang entry, weapons trafficking and, possibly, terrorist entry….South Texas now rivals California and Arizona as the primary entry point for Mexican methamphetamines into the United States. (National Drug Intelligence Center, 2007: 2)

The U.S. Department of Justice acknowledges the geographic challenges and threats to the south Texas region by referring to both its geography and transportation infrastructure when it reports that

the Rio Grande is easily breached at a number of low–water crossings by traffickers on foot and in vehicles and by maritime conveyances along deeper stretches of the river. The south Texas Gulf Coast is vulnerable to traffickers who use maritime conveyances….The transportation infrastructure in the region, including networks of interstate, U.S. highways and state highways, facilitate the transportation of illicit drugs shipments from the border area to interior drug markets….U.S. highways 77 and 281 are the principal transportation routes that traverse the Lower Rio Grande Valley. (National Drug Intelligence Center, 2007: 5–6).

Three of the four counties in the Rio Grande Valley provide seven bridges as points of entry to northern Mexico with another one under construction to expand traffic access between Reynosa, Nuevo Leon, and the Texas county of Hidalgo. Clearly, the investment of tax resources by regional, state, and federal governments to improve the infrastructure and provide access for legal commerce and related transportation by residents is also being extensively used for illicit border trade.

Andreas claims that the post–9/11 policies of the U.S. federal government to deter terrorism created a borderlands landscape where policies instead evolved to support administrative and judicial practices that affect immigration and the cross–border economy. He further contends that

the southern U.S. border was also partly militarized through the "war on drugs" with the military drafted to play an interdiction support role. At the same time as policymakers were attempting to make the border more secure, they were also making it more business friendly to accommodate the requirements of NAFTA. The seemingly paradoxical end result was the construction of both a borderless economy and a barricaded border. The border has become both more blurred and more sharply demarcated than ever before. (2003: 14)

Orrenius and Coronado provide additional insights about this situation in their analysis of the relationship between illegal immigration, border enforcement, and crime rates along the Mexico–U.S. border. Among some of these observations are the following:

On the border, the cost of crime is particularly important since many border counties are already reeling under public expenses associated with high immigration and poverty rates….Also of considerable interest are economic conditions in Mexico and their impact on border crime rates in the United States. They do not seem to matter to property–related or overall crime, but from data, the results suggest that higher wages and a higher value of the peso are correlated with access to the United States such as frecuency of border crossings –which might increase the opportunity for cross–border crime– or with the demands for illicit drugs, which is also correlated with violent crime on both sides of the border. (2005: 1–23)

In their analysis of recent national data, López and Light, writing for the Pew Hispanic Center, reported that

sharp growth in illegal immigration and increased enforcement of immigration laws have altered the ethnic composition of offenders sentenced in federal courts. In 2007, Latinos accounted for 40 percent of all sentenced federal offenders –more than triple their share (13 percent) of the total U.S. adult population. The share of all sentenced offenders who were Latino in 2007 was up from 24 percent in 1991. (2009: 1–6)

This report segregates the various offenses detailed by United States Sentencing Commission (USSC), and the data show that of all Hispanics sentenced in federal courts in 2007, 48 percent were convicted of immigration offenses, 37 percent of drug offenses and 15 percent of other offenses. I would propose that a microanalysis of this data may provide insights about how these offenses compared within the Rio Grande Valley. An all–encompassing assessment of the challenges to homeland security and the geographic infrastructure of this region is also provided by Andreas, when he writes, "Thus the borders are being fortified not against state–sponsored military invaders but against transnational law evaders. The awkward policy dilemma is that these clandestine actors use the same cross–border transportation and communications networks that are the arteries of a highly integrated and interdependent economy" (2003: 14).

The challenges presented in the model have some limitations since space constraints make it infeasible to consider every conceivable strand. However, the model does provide a context to identify other issues that may be observed by other researchers. It is necessary to focus now on the challenges present within the model's demographic axis.

THE DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES

Friedland and Summer believe that

society's future is not determined solely by demographic change. Focusing on the anticipated growth in population by age group is just too simplistic an approach. Rather, the future is shaped by the choices made –or not made– individually or collectively, bounded by the limits in resources and in particular knowledge. Knowledge is at the heart of gains in productivity, economic growth, and the advances in medical care, agriculture, communication, transportation, and the environment. (2005: v)

This section will focus on a select number of demographic strands (presented in figure 2): the characteristics of the population, colonias, the educational profile of the region's inhabitants, and the economic status of the region.

The overwhelming Mexican–American demographic composition of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley presents a unique micro reference to evaluate how this population has fared in its social–economic development. The U.S. Census Bureau groups this population nationally with other ethnic subgroups under the rubric of "Hispanic" (American Communities Survey, 2008). Prior to the 1970 general census, the U.S. Census Bureau, under orders from Congress, created the term "Hispanic" (Tienda and Mitchell, 2006: 1–15).

The most recent data for the four counties of the Rio Grande Valley, when stratified for analysis, present a very diverse population: the total of 1 148 853 inhabitants are 90.25 percent Mexican American, of whom 26 percent are foreign born, primarily in Mexico (U.S. Census Bureau: 2009). According to the Office of the State Demographer (2007), the population is growing at an estimated annual rate of between 2 percent and 4 percent. By all accounts, this is a young population with a median age of 28, compared to the median age of 36 years for the rest of the United States. The population is predominately bilingual with Spanish as the language spoken at home and in the social–cultural milieu, according to the U. S. Census Bureau (American Communities Survey, 2008). The University of Texas School of Public Health at Houston conducted the first comprehensive study of the status of health in this region in 2004. Lead researcher R. Sue Day presents data showing that 44 percent of residents do not have health insurance, compared to 28 percent for the rest of Texas, presenting another critical policy challenge to all levels of government (2004: 32–34).

There is a sub–group that also merits specific analysis here due to its geographic placement in the region and its demographic profile. This sub–group consists of Mexican Americans who reside in segregated and unincorporated communities known as "colonias." The Texas Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas offers this definition: "Colonia is a Spanish term for neighborhood or community. In Texas, colonia refers to an unincorporated settlement that may lack basic water and sewer systems, paved roads, and safe and sanitary housing" (2009: 1). The Office of the Texas Secretary of State (2006) commissioned the first comprehensive mapping study of colonias in Texas and 2 019 were identified along the Texas/Mexican border. Of these, to date, 1 850 have been mapped and plotted on a Global Positioning System (GPS) map. The mapping grid identified 1 364 colonias in the four counties of the Rio Grande Valley with a total population of 238 480. The majority of these colonias (934) are in Hidalgo County.

The Texas Secretary of State (2006), the Texas Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas (2009), Zeeo, Slottje, and Vargas–Garcia (1994), and Soden (2006) unanimously agree on the characteristics and challenges evident in borderland colonias. Soden provides the following assessment of the challenges encountered by colonias in his report on the Texas border counties:

Colonias are measures of land ownership that cannot be tracked through traditional markets and require a substantial investment in infrastructure to meet minimum standards in many areas. Colonias are areas that require sewer lines or septic systems, water delivery, roads, and flood control. In addition, they get lost due to a lack of political clout stemming from isolation geographically and from many governmental institutions, compounded by lower socioeconomic status. The relationship between socioeconomic factors is well established by researchers. Colonia residents, being among the poorest, least educated, and who are often unauthorized immigrants, lack political participation and representation. (2006: 154–156)

The challenges grounded in a region's educational capacity are also a matter that requires deliberation here. Hargroves and Smith (2005), Gibson and Rhi–Perez (2003), Sharp (1998), Acevedo, Rodriguez and De los Reyes (2003), and Sharp (1998) all hold to the proposition that education is the foundation for all economic and regional development to advance the quality of life of residents. Soden's assessment is that

education is perhaps the most important component of regional economic growth. As an example, one need only compare San Diego County to Cameron County, the counties at the opposite ends of the southwestern border. In San Diego County, 30 percent (29.6 percent) of the population has earned a four–year college degree or higher. By contrast, Cameron County reports a rate that is less than half of San Diego (13.3 percent). The same trend holds for high school graduation rates and emphasizes what has been promoted for decades –education matters! Over the course of a work life, individuals with a college degree will earn one million dollars more than their high school graduate counterparts, and the gap widens for non–high school graduates. These education disparities highlight the problems border counties are facing in the educational arena. The root of these problems lies in the fact that the education shortfall in the region exists at all levels of the education system, from pre–kindergarten through college, and prevails among all age groups. Unless these trends change significantly, the simple fact is the border will never catch up with the U.S. mainstream. The level of change necessary is made abundantly clear by ranking the border counties as a 51st state. (2006: 130)

Hargroves and Smith believe that "education is a cornerstone of sustainable development and capacity building in regions" (2006: 430–431). The Intercultural Research Development Association (2008) recently cited the four counties of the Rio Grande Valley as having a cumulative public school dropout/attrition rate of 40 percent for all students regardless of ethnicity or gender, while the rate for the rest of Texas is 23 percent. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau's American Survey (2008) show that only 15 percent of residents of these four counties have a bachelor's degree or higher post–secondary education. Soden (2006: 132) believes that the relative youth of the border population, with 28.5 percent under eighteen years of age, make the availability and accessibility to higher education a greater imperative to the Texas system of higher education.

The South Texas Higher Education Initiative of 1987 resulted in the current composition of six institutions of higher education between El Paso and Brownsville (Sharp, 1998). Clearly, these institutions have made a difference in the enrollment and graduation of border region residents (Sharp, 1998). Soden views these developments as insufficient to make up the discrepancies with the rest of Texas (2006: 132–135). He claims that in the past 10 years participation in higher education in border counties has only increased 1 percent, while in the rest of the country, it has increased by 4 percent. He believes that

students in border counties, compared to their counterparts in non–border counties, disproportionately face the choice between education and work based on family and personal income needs. One result is that completion of college takes longer since the role of full–time student is an unaffordable luxury. Federal support of programs to keep students in college in border counties may be necessary to accelerate the regional demand for a college educated work force.

Education may be the greatest challenge facing the southwest border counties, regardless of level. It may be the area that also requires the most innovation to develop educational strategies that will reduce drop–out rates, enhance completion at all levels, and support "catching–up" remedial activities in community colleges and universities that have proven to be a key factor in college completion. (2006: 132)

The continued sustainability and expansion of border educational institutions, both at the public and post–secondary level is contingent on economic and political factors that are affecting the United States and the world as a whole. The gains and opportunities presented by the border educational institutions are at risk and their outcomes, whether negative or positive, cannot be evaluated at this time. This situation presents a long–term policy challenge to all levels of government on the north side of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo.

This region's economic wherewithal has been unstable for some time, even before the current fiscal crisis. Furthermore, Soden (2006) proposes that the factors evident in the 1990s, as reported by Sharp (1998), are still present and persistent. Soden (2006), Hargroves and Smith (2006), and Friedland and Summer (2005) agree that economic prosperity, sustainable development, and accessing opportunities are linked to literacy, education, and training. The issue of the current global financial crisis directly impacts education, and, of course, economic stability and its full effect on this region is yet to be determined.

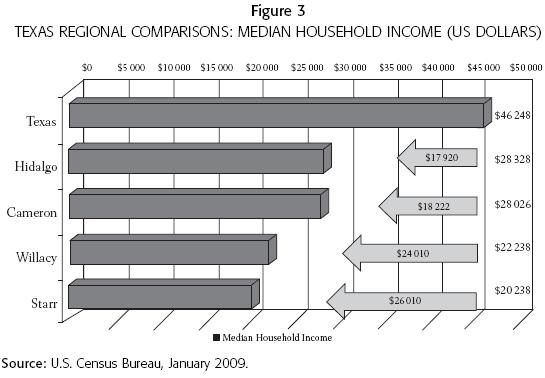

Soden (2006), Gibson and Rhi–Perez (2003), and Acevedo, Rodriguez, and De los Reyes (2003) provide data showing that the Rio Grande Valley's economic profile is inconsistent and regressive compared to the rest of the United States and the rest of Texas. According to Soden, poverty has remained basically unchanged since 1990, and he claims that "throughout the 1990s, above average growth rates were not sufficient to tackle the chronic problems of low income and poverty, especially with population growth along the border outpacing income and job gains, the baseline of that decade's census" (2006: 56). Acevedo, Rodriguez, and De los Reyes provide data demonstrating that 28 percent of household income in the valley's two largest counties, Cameron and Hidalgo, came from government payments (2003). They proposed that such an economy is weak and vulnerable since it relied on income not generated by production such as technology, manufacturing, or trade. A recent analysis of 2009 census data by Acevedo (figure 3) indicates that the median income of households in the Rio Grande Valley is as much as 35 percent smaller than household incomes in the rest of the state of Texas.

López provides another analysis, stating that "despite rapid job creation, the Valley remains relatively poor. The McAllen–Edinburg–Mission metropolitan statistical area (MSA) ranks last among the nation's 361 MSAs, with a per capita income of $15 184 a year, less than half the national average of $31 472. The Brownsville–Harlingen MSA comes in next to last at $16 308" (2006: 2–3). A recurring theme has emerged about the impact of education on a region's sustainable economy. Gibson and Rhi–Perez (2003), Soden (2006), and most recently López (2006) have reiterated this proposition. López's analysis of the economy of the Rio Grande Valley led to the projection that

longer term, the Valley faces challenges. Consistent and rapid job growth since the early 1990s has helped the region shed its reputation for high unemployment, but the economy hasn't been catching up with national and state levels of per capita income. Most likely, low educational attainment lies at the heart of this. The region has been unable to improve the education level of its work force relative to the state since the 1970s. In 2000, the percentage of the labor force with less than a high school education averaged 52 percent in the Valley and 24 percent in Texas, according to the Census Bureau. If the Valley were to reduce its high school dropout rate to the state average, income would go up an estimated $2 billion a year. (2006: 3).

These geographic and demographic challenges, as presented, were guided by Paasi's theory on regional institutionalization. However, the impetus for this article was Harvey's recommendation that "at the North American level, an analysis that compares the process of regional institutionalization on different scales and according to different historical, political, and administrative modes appears necessary in the context of the increasing integration brought on by the NAFTA treaty" (2006: 91).

While NAFTA is a critical variable, it was the inclusion and consideration of the historical, political, and administrative context that generated the guiding question for this study and the model proposed as a reference for analysis.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The purpose of this article was to answer the question: How do history, geography, and demography challenge the present and future regional institutionalization of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley? The data presented, analyzed, and reviewed demonstrate that the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley is indeed in a constant state of institutionalization as proposed by Paasi (1986), Gilbert (1988), Harvey (2006), and other theorists. By applying present theories to a historical context and then analyzing data to explain present conditions, this article brought forth selected variables to demonstrate how this region's institutionalization is being challenged. The region's legitimacy is not at risk, but emerging forces such as immigration, the global economy, bi–national crime, the environment, and residents' low educational levels may impede sustainability and fragment institutionalization of the Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley.

This author recommends that additional strands with corresponding data be added to the proposed model (figure 2) and analyzed and benchmarked so that a formative evaluation can be undertaken of economic, geographic, and demographic shifts in the region. It is also imperative that this region's relationship to the Mexican states south of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo be studied further within the framework of both regional and international policy relating to shared development and expansion of human and intellectual capital.

Hopefully, the substantive theoretical constructs used in this article can guide further research about institutionalization and sustainable development. I also recommend that additional research apply the essential elements of the model used here to study regional phenomena in other parts of Mexico, Canada and the United States. However, it is this observer's position that the theories of regionalization, institutionalization, and sustainable development need to be invigorated by constant qualitative research that works to expand theory by identifying and explaining the forces that occur when humans act within a certain geographic space.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Acevedo, B.A., I. Rodriguez, and O. de los Reyes. 2003. An Updated Overview of the Texas Border, Brownsville, Texas, The Cross Border Institute for Regional Development, The University of Texas at Brownsville, http://blue.utb.edu/cbird/utb–tscfpageformat/homereports.htm, accessed January 12, 2009. [ Links ]

Alba, Francisco. 1984. "Mexico Northern Border: A Framework of Reference," in Sepúlveda and Albert E. Utton, The U.S.–Mexico Border Region: Anticipating Resource Needs and Issues to the Year 2000, El Paso, Texas, Texas Western Press. [ Links ]

American Community Survey. 2008. The United States Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/acs/www/ accessed May 2, 2008. [ Links ]

Andrade, Hope. 2009. The Colonias Initiatives Program, Austin, Texas Border and Mexico Affairs Division/Office of the Texas Secretary of State, http://www.sos.state.tx.us/border/colonias/, accessed January 15, 2009. [ Links ]

Andreas, Peter. 2003. A Tale of Two Borders: The U.S.–Mexico and U.S.–Canada Lines after 9–11, working paper no. 177, May 2003, San Diego, California, The Center for Comparative Immigration Studies/University of California. [ Links ]

Arreola, Daniel D. 2002. Tejano South Texas: A Mexican American Cultural Province, Austin, Texas, University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Day, R. Sue. 2004. Nourishing the Future: The Case for Community–Based Nutrition Research in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, Houston, Texas, University of Texas School of Public Health. [ Links ]

Deeken, A. 2006. Youth and Commerce Define the Texas Border Towns of Brownsville, Harlingen and McAllen, M & M Marketing Medios, http://www.marketingmedios.com/, accessed June 14, 2008. [ Links ]

Environmental Defense Fund. 2003. The Forgotten River: the Struggle to Revive a Once Bountiful Oasis, http://www.edf.org/article.cfm?ContentID=2927, accessed January 20, 2008. [ Links ]

Environmental Protection Agency. 2002. U.S.–Mexico Border 2012 Program, http://www.epa.gov/usmexicoborder/directory.html, accessed January 15, 2009. [ Links ]

Friedland, Robert B. and Laura Summer. 2005. Demography Is Not Destiny, Revisited, Washington, D.C., Georgetown University Center on Aging. [ Links ]

Gaffield, Chad. 1991. "The New Regional History: Rethinking the History of the Outaouais," Journal of Canadian Studies issue 26, Peterborough, ON, Trent University, pp. 64–79. [ Links ]

Gibson, David and Pablo Rhi–Perez. 2003. Cameron County / Matamoros: At the Crossroads, Assets and Challenges for Accelerated Regional and Bi–national Development, Brownsville, Texas, University of Texas/Texas Southmost College/The Cross Border Institute for Regional Development. [ Links ]

Gilbert, Anne. 1988. "The New Regional Geography in English and French–Speaking Countries," Progress in Human Geography vol. 12, no. 2, June, pp. 208–228. [ Links ]

Gilmer, R.W. and Jesus Cañas. 2005. Industrial Structure and Economic Complementarities in the City Pairs on the Texas–Mexico Border, working paper no. 0503, Dallas, Texas, Federal Bank of Dallas. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, David, G. 1999. "Migration, Emergent Ethnicity and the 'Third Space': The Shifting of Nationalism in Greater Mexico," The Journal of American History vol. 86, no. 2, September, pp. 481–517. [ Links ]

Hamin, Elisabeth M. and Daniel J. Marcucci. 2008. "Ad Hoc Rural Regionalism," Journal of Rural Studies vol. 24, issue 4, October, pp. 467–477. [ Links ]

Hargroves, Karlson "Charlie" and Michael H. Smith. 2005. The Natural Advantage of Nations: Business Opportunities, Innovation and Governance in the 21st Century, Gateshead, UK, The Bath Press. [ Links ]

Harvey, Fernand. 2006. "Identity and Scales of Regionalism in Canada and Quebec: A Historical Approach," Norteamérica. Revista académica, year 1, no. 2, July–December, pp. 77–97. [ Links ]

Intercultural Research Development Association. 2009. "Attrition Rates in Texas Public Schools by Race–Ethnicity, 2007–08," http://www.idra.org/Research/Attrition/Attrition_Rates_07_08/. [ Links ]

Kay, John. 2004. "Culture and Prosperity: Why Some Nations are Rich But Most Remain Poor," New York, Harper Collins Books. [ Links ]

Kearney, Milo and A. Knopp. 1995. Border Cuates: A History of the U.S.–Mexican Twin Cities, Austin, Texas, Eakin Press. [ Links ]

López, José Joaquín. 2006. Dynamic Growth in the Rio Grande Valley no. 2, March–April, Dallas, Texas, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. [ Links ]

López, Mark Hugo and Michael T. Light. 2009. A Rising Share: Hispanics and Federal Crime, Washington, D.C., Pew Hispanic Center, http://pewhispanic.org/reports/report.php?ReportID=104, accessed February 13, 2009. [ Links ]

Maxwell, Joseph A. 1996. Qualitative Research Design, An Interactive Approach, London, UK, Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Metz, Leon. 1989. Border: The U.S.–Mexico Line, El Paso, Texas, Mangan Books. [ Links ]

Miles, M. B. and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd. ed., Thousand Oaks, California, Sage Publications. [ Links ]

Miller, Tom. 1981. On the Border: Portraits of America's Southwestern Frontier, Tucson, Arizona, The University of Arizona Press. [ Links ]

Montejano, David. 1987. Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836–1986, Austin, Texas, University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Murdock, S. H., M.N. Hoque, M. Michael, S. White, and B. Pecotte. 1997. The Texas Challenge: Population Change and the Future of Texas, College Station, Texas, Texas A & M University Press. [ Links ]

National Drug Intelligence Center. 2007. "South Texas High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area Drug Market Analysis (HIDTA), Annual Reports," in Department of Homeland Security Annual Agency Reports, Washington, D.C., http://www.scribd.com/doc/346517/05322swb–south–texas, accessed February 9, 2009. [ Links ]

Office of Management and Budget. 2007. Update of Statistical Area Definitions and Guidance on their Uses, OMB Bulletin no. 08–01, November 20, Washington, D.C., Office of the Director. [ Links ]

Office of the Texas State Demographer. 2008. Sex and Race/Ethnicity Total Population by Migration Scenario for 2000–2040 in 1 year increments, San Antonio, Texas, The Institute for Demographic and Socioeconomic Research, University of Texas, http://txsdc.utsa.edu/, accessed February 4, 2008. [ Links ]

Opie, John. 1998. "Moral Geography in High Plains History," The Geographical Review vol. 88, issue 2, New York, The American Geographical Society. [ Links ]

Orrenius, Pia M. and Roberto Coronado. 2005. The Effects of Illegal Immigration and Border Enforcement on Crime Rates along the U.S.–Mexico Border, working paper no. 131, San Diego, California, Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of San Diego. [ Links ]

Paasi, Anssi. 1986."The Institutionalization of Regions: Theoretical Frameworks for Understanding the Emergence of Regions and the Constitution of Regional Identity," Fennia vol. 164, issue 1, pp. 105–146. [ Links ]

–––––––––– 1991. "Deconstructing Regions: Notes on the Scales of Spatial Life," Environment and Planning vol. 23, issue 2, pp. 239–256. [ Links ]

Rebert, Paula. 2001. La Gran Línea: Mapping the United States–Mexico Boundary, 1848–1857, Austin, Texas, University of Texas Press. [ Links ]

Rio Grande Valley Texas. 2008. Winter Newsletter, http://www.rgvtexas.com, accessed January 8, 2009. [ Links ]

Saldívar, Ramon. 2006. The Borderlands of Culture: Américo Paredes and the Transnational Imaginary, Durham, North Carolina, Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2008. ¿Son las áreas protegidas? http://www.conanp.gob.mx/q_anp.html, accessed January 21, 2009. [ Links ]

Sharp, John. 1998. Bordering the Future: Challenges and Opportunity in the Texas Border Region, Austin, Texas, Office of the Texas State Comptroller, http://www.window.state.tx.us/border/ch08/folk.html, accessed October 12, 2008. [ Links ]

Soden, Dennis L. 2006. At the Crossroads: U.S./Mexico Border Counties in Transition, IPED Technical Reports, Institute for Policy and Economic Development, University of Texas at El Paso. [ Links ]

Soja, Edward W. 1996. Thirdspace–Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real–and–Imagined Places, Malden, Massachusetts, Blackwell. [ Links ]

–––––––––– 2000. Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions, Malden, Massachusetts, Blackwell. [ Links ]

Suárez–Mier, Manuel. 2007. "A View from the South," Foreign Services Journal, October, pp. 17–22. [ Links ]

Texas Border Business. 2009. http://www.texasborderbusiness.com, accessed February 1, 2009. [ Links ]

Texas Department of Transportation Mobility Plans. 2008. Pharr, Texas District Transportation Statistics, Fiscal Year 2008, http://www.txdot.state.tx.us/default.htm, accessed December 3, 2008. [ Links ]

Texas Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. 2009. Texas Colonias: A Thumbnail Sketch of the Conditions, Issues, Challenges and Opportunities, http://dallasfed.org/sitemap.html, accessed February 3, 2009. [ Links ]

The Rio Grande Valley Partnership. 2009. Membership Directory, http://www.valleychamber.com/, accessed January 21, 2009. [ Links ]

Tienda, Marta and Faith Mitchell. 2006. Hispanics and the Future of America, Washington, D.C., The National Academies Press. [ Links ]

Tucker, Thomas P. 2001. The Final Fury: Palmito Ranch, the Last Battle of the Civil War, Mechanicburgh, PA, Stackpole Books. [ Links ]

U.S. Census Bureau. 2008. American Communities Survey, available online at http://www.census.gov/acs/www/, accessed May 2, 2008. [ Links ]

U.S. Department of Agriculture's Agricultural Marketing Service 2008. http://www.marketnews.usda.gov/, accessed January 12, 2009. [ Links ]

United States Department of Justice. 2008. "Southwest Border South Texas High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area (2005–2006)," Annual Report, Washington, D.C., Department of Homeland Security, http://www.scribd.com/doc/346517/05322swb–south–texas?ga_from_send_to_friend=1, accessed June 21, 2008. [ Links ]

Valley Water Summit. 2005. "Environmental Issues White Paper," February 23, Harlingen, Texas, Marine Military Academy, http://www.valleywatersummit.org/papers.html, accessed January 11, 2009. [ Links ]

Vargas, Z. 1999. "Early Mexicano Life and Society in the Southwest, 1821–1846," in Z. Vargas, ed., Major Problems in Mexican American History, New York, Houghton Mifflin. [ Links ]

Velázquez, M. A. 2007. "Changing Representation of the Border," in E. Ashbee, H. B. Clausen and C. Pedersen, eds., The Politics, Economics, and Culture of Mexican–U.S. Migration, New York, Palgrave Macmillan. [ Links ]

Williams, Roger. 2006. A Report Relating to the Coordination of Colonias Initiatives and Services to Colonias Residents. Austin, Texas, Office of the Texas Secretary of State, http://www.sos.state.tx.us/border/colonias/, accessed February 27, 2008. [ Links ]

Wong, C.M., C.E. Williams, J. Pittock, U. Collier, and P. Schelle. 2007. World's Top 10 Rivers at Risk, Gland, Switzerland, World Wild Life Fund International, http://www.worldwildlife.org/home–full.html. [ Links ]

Wu, JunJie and Munisamy Gopinath. 2008. "What Causes Spatial Variations in Economic Development in the United States?" American Journal of Agricultural Economics vol. 90, no. 2, pp. 392–408. [ Links ]

Young, Edward. 2004. Catarino Garza's Revolution on the Texas–Mexico Border, Durham, North Carolina, Duke University Press. [ Links ]

Zavaleta, Antonio N. 1986. "The Twin Cities: A Historical Synthesis of the Socio–Economic Interdependence of the Brownsville–Matamoros Border Community," in M. Kearney, ed., Studies in Brownsville History, Brownsville, Texas, Pan American University at Brownsville Press. [ Links ]

Zeeo, Dianne C., J. Daniel Slottje, and Jesus Vargas–Garcia. 1994. Crisis on the Rio Grande: Poverty, Unemployment, and Economic Development on the Texas–Mexico Border, Boulder, Colorado, Westview Press. [ Links ]