Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Contaduría y administración

versión impresa ISSN 0186-1042

Contad. Adm no.231 Ciudad de México may./ago. 2010

Artículos de investigación

Cross border industries in Mexico with low organizational attachment. Case study

Empresas maquiladoras en México con bajo compromiso organizacional: estudio de caso

Blanca Garcia* y John Cox**

* Profesora investigadora, Facultad de Ciencias Administración y Sociales. Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, blanca_garcia@uabc.mx

** College of Business, University of West Florida, jcox@uwf.edu

Fecha de recepción: 29.08.2008

Fecha de aceptación: 26.01.2010

Abstract

Cross Border Industries, also known as maquiladoras in Northern Mexico, are currently facing the problem of low organizational attachment among production workers. Direct workers often perceive little commitment to their company, and turnover rates in the plants average; e.g., about 10 per cent per month in Tijuana. Other places like Ensenada (1 hour away from Tijuana) face turnover rates that are lower than 10 percent, but still much higher than is desirable. In this study we examine turnover and job satisfaction through a turnover model. Variables dealing with co–workers, job security, and the job itself demonstrated a strong independent relationship. An analysis of data made in SPSS from 100 production workers within an outsourcing manufacturing maquiladora showed that the desire continually to seek a new job is positively associated with turnover intentions and negatively associated with organizational commitment. This finding can be of guidance to managers and management scholars attempting to understand and combat turnover and reinforce organizational attachment in Northern Mexico.

Keywords: maquiladora, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, work motivation, Mexico, job security, turnover, job values.

Resumen

La industria maquiladora de la frontera del norte de México está enfrentando actualmente el problema del bajo compromiso organizacional entre sus trabajadores de producción. Los empleados directos a menudo perciben muy poco compromiso hacia su organización y las tasas de rotación en las plantas fluctúan en un promedio de 10% mensual en Tijuana. Otras ciudades como Ensenada (a una hora de Tijuana) experimentan tasas menores a 10%, pero aun más altas de lo deseable. En este estudio, se examina un modelo de rotación de personal y satisfacción en el empleo. Las variables que se utilizan son las de los compañeros de trabajo, seguridad en el empleo y el contenido de trabajo. Las variables demuestran una relación independiente alta. Un análisis realizado en el programa SPSS a cien trabajadores de producción de una empresa maquiladora demuestra que el deseo continuo de buscar trabajo está positivamente asociado con las intenciones de rotar y negativamente asociado con el compromiso organizacional que perciben. Este hallazgo puede servir de guía a los gerentes y académicos que intentan entender y combatir la rotación y reforzar el compromiso organizacional en el norte de México.

Palabras clave: maquiladoras, compromiso organizacional, satisfacción laboral, motivación en el empleo, México, seguridad laboral, rotación de personal, valores del empleo.

Introduction

"Maquiladora" is a word that started its use from colonial Mexico where "maquila" was a charge that millers collected for processing other people's grain. Today, the term applies to companies that process or assembles components imported into Mexico that are then re–exported.

The maquiladora program started at the end of the Brazero Program. As Aten & Burken (1999) explain, this program had allowed Mexican nationals to work temporarily in the U.S. agricultural sector. "This resulted in a huge influx of Mexican workers from the interior of the country to the border cities seeking employment. In 1964, the United States government ended the Brazero Program due to domestic political pressures. Many of the workers stayed in the border cities hoping the program would be reinstated and continued looking for jobs. The Mexican government responded in 1965 with the Border Industrialization Program to alleviate the high unemployment in the region and attract foreign investment and technology to Mexico. The maquiladora program was born out of this in 1966" (Aten & Burken, 1999).

Nowadays, maquiladoras represent an important activity for the northern states of Mexico, where their investment has lowered the unemployment rates greatly. Nevertheless, for a long time, maquiladoras have faced a low organizational commitment among production workers. Direct workers often perceive little commitment to their company, and turnover rates in the plants average; e.g., about 10 per cent per month in Tijuana (Garcia & Rivas, 2007).

Job satisfaction has been linked to turnover (Sweeney and Boyle, 2005). No matter the industry, and no matter the country, perhaps the most diffcult continuing problem of organizations is that of obtaining and retaining good human resources. While the stated percent of employment/ unemployment may vary between industries by a few percentage points, there is always a need on the part of the organization to recruit and retain good workers.

Affective Commitment has been linked to turnover too. Mowday, Porter and Steers, (1982) and Meyer, Paunonen, Gellatley, & Goffin, and Jackson, (1989) have found that committed employees are more likely to remain with the organisation and strive towards the organisation's mission, goals and objectives (Riley, 2006). Organisational commitment is defined as the degree to which the employee feels devoted to their organisation (Spector, 2000).

The problems of human resources are usually exacerbated by conditions that may be specific to that industry, location, or other attributes. In this research, Human Resources (HR) is a term applied to employees that work at the organization. A previous study (Garcia and Cox, 2007a) was conducted in an assembly/manufacturing plant in Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico, investigating the effects of the implementation of a 5 S program. During the course of that study, a number of issues arose that were ancillary to the specific 5 S program, and these dealt with the workers' organizational attachment and job satisfaction.

Within the assembly/manufacturing plant, the level of turnover was high, with an accompanying low organizational attachment and low job satisfaction. Within this Mexican study, a number of issues came into play. These included, but were not limited to, the following.

Gender – The workers in the plant were predominately female.

Educational Level – The average educational level within the workforce was well below college level.

Marital Status – Overall, the percent of the workers who were married was close to 50%.

Age – The average age of the workers in the plant was 23 years old.

Children – A large percentage of the workers had children, and a large percentage of these were sole support providers.

An issue exacerbating all the others was the following.

Other Job Opportunities – The study plant is located in an area of many maquiladora plants, and most of the plants and jobs require low levels of skill, short training times, and low levels of formal education. All of the maquiladora plants share the problem of maintaining a labor force, and most have high turnover due to the prevailing "grass is greener" mentality among the workers. Accompanying this, of course, is the fact of fairly limited opportunities to move upward in any given plant's hierarchy.

All of the above, plus other factors, mitigate for a [relatively] low level of job satisfaction and accompanying low level of organizational attachment/commitment. From the management and human resources side, no progress is made if 50 newly–hired workers come in the front door, but 50 workers leave through the back door to an easily obtainable job at another company. Such a revolving door HR experience is very costly, since costs include not only those of recruiting, but also of added training, plus plant issues of lower production and quality due to a continuing stream of workers with little or no experience.

In another unrelated study by the authors in 2007 (Garcia and Cox, 2007b), the turnover rate in a medical products assembly plant hovered at thirteen percent per month. This level of turnover, unfortunately, tracks well with another research study published in 1993 by Carrillo and Santibanez (Carillo & Santibanez, 1993). Their study found the turnover rate in the Tijuana maquiladoras in 1989 averaged 12.7 percent per month in the areas of electronics, auto parts, and clothing. Thus, in some respects, it appears little has changed in some areas in the last [almost] twenty years, and the worker revolving door is not unique to one company or industry.

Subsequent to the 5 S studies, it was decided to look further into the issue of low organizational attachment, and to broaden the study to include additional workers in Mexico. The study was applied in a fshing lure manufacturing company that has been in Ensenada for more than 15 years. They came from Yakima, Washington and extended their production facilities in Ensenada, keeping their mother plant in Washington. This is a small company with 120 employees. They manufacture lures for Yakima Bait Corporation, who has manufactured fshing lures and tackle for more than 50 years. They have been facing challenges as to cope with a different cultural environment and to adapt to Northern Mexican's labor environment. Even thought their turnover hasn't been really high, employees show low commitment and their productivity hasn't grown as much as they expected. Their facilities in Washington have Mexican labor too and their productivity is way higher than the Mexican one.

For the maquiladora manufacturing industries in the northern part of Mexico, primarily set up due to outsourcing of manufacturing from the U.S., affective commitment is not present in most employees (Affective commitment refers to employees' emotional attachment, identifcation with, and involvement in the organization.). The major reasons seen for this lack of commitment or attachment is the fact that there appears to be no real involvement with the organization and employees do not develop a strong affective commitment due to low job satisfaction (Sweeney and Boyle, 2005).

The purpose of this study was to investigate the perceptions of 100 direct employees and to examine the relationship between their perceived levels of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intentions within an outsourcing manufacturing maquiladora in the Baja California border of Mexico. This study contributes to the literature by extending previous research to include turnover intentions as a consequence of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Studies to investigate and analyze relationships among job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intentions in maquiladora industries have been scarce.

Literature Review

Work motivation, job satisfaction and organizational commitment

Employee organizational commitment has been a subject of interest for many researchers (Meyer & Allen, (1997), Loui (1995), Wiener & Vardi (1980), Angle & Perry (1981), Jermier & Berkes (1979), DeCotiis & Summers (1987), Bycio, Hackett, & Allen (1995), Brown (2008), etc.

According to Brown, many factors influence employee commitment. These include commitment to the supervisor, occupation, profession, or career (Meyer & Allen, 1997 in Brown 2003).

Brown (2003) refers to Meyer & Allen (1991) stating that they developed a framework designed to measure three different types of organizational commitment: (a) Affective commitment refers to employees' emotional attachment, identifca–tion with, and involvement in the organization. Employees with a strong affective commitment stay with the organization because they want to. (b) Continuance commitment refers to employees' assessment of whether the costs of leaving the organization are greater than the costs of staying. Employees who perceive that the costs of leaving the organization are greater than the costs of staying remain because they need to. (c) Normative commitment refers to employees' feelings of obligation to the organization. Employees with high levels of normative commitment stay with it because they feel they ought to.

In general, organizational commitment is considered a useful measure of organizational effectiveness (Steers, 1975). In particular, "organizational commitment is a "multidimensional construct" (Morrow, 1993) that has the potential to predict organizational outcomes such as performance, turnover, absenteeism, tenure, and organizational goals" (Meyer & Allen, 1997, p. 12). Also, in a study involving 109 workers, Loui (1995) examined the relationship between the broad construct of organizational commitment and the outcome measures of supervisory trust, job involvement, and job satisfaction. In all three areas, Loui (1995) reported positive relationships with organizational commitment. More specifically, perceived trust in the supervisor, an ability to be involved with the job, and feelings of job satisfaction were major determinants of organizational commitment.

Angle & Perry (1991) undertook a study to determine the effect that organizational commitment had on turnover. The participants included 1,244 bus drivers. Findings revealed a negative relationship between turnover and organizational commitment. In short, employees who intended to leave the job were not committed to the organization.

Wiener & Vardi (1980) looked at the effect that organizational commitment had on commitment to the job and career commitment. Their participants included 56 insurance agents and 85 staff professionals. The researchers reported positive relationships between organizational commitment: normative commitment and affective commitment.

Jermier & Berkes (1979) collected data on organizational commitment from over 800 police offcers. The researchers were investigating the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Findings revealed that employees who were more satisfed with their job had higher levels of organizational commitment.

DeCotiis & Summers (1987) undertook a study of 367 managers and their employees. The researchers examined the relationship between organizational commitment and the outcome measures of individual motivation, desire to leave, turnover, and job performance. Organizational commitment was found to be a strong predicator for each of these outcome areas.

In nine studies involving 2,734 persons, Dunham, Grube, & Castaneda (1994) examined how participatory management and supervisory feedback influenced employee levels of affective, continuance, and normative commitment. The researchers found that when supervisors provided feedback about performance and allowed employees to participate in decision–making, employee levels of affective commitment were stronger than either continuance or normative. That is, employees indicated staying with the organization was more related to wanting to, rather than needing to or feeling they ought to. It would seem this feeling would be particularly true in a labor atmosphere such as found in an area heavy with maquiladora plants; thus, rife with other job opportunities.

In a study of 238 nurses, Cohen (1996) investigated the relationship between affective, continuance, and normative commitment, as well as the commitment types of work involvement, job involvement, and career commitment. Findings revealed that affective commitment was more highly positively correlated with all the other types of commitment. In other words, employees who remained with the organization because they wanted to were more likely to exhibit higher levels of commitment to their work, their job, and their career.

Irving, Coleman, & Cooper (1997) investigated the relationship between affective, continuance, and normative commitment and the outcome measures of job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Total participants for the study included 232 employees. Results revealed that job satisfaction was positively related to both affective and normative commitment.

However, job satisfaction was negatively related to continuance commitment. All three types of commitment were negatively related to turnover intentions, with continuance commitment having the strongest negative relationship.

Cohen & Kirchmeyer (1995) undertook a study to investigate the relationship between affective, continuance, and normative commitment. Their participants included 227 nurses from two hospitals. The researchers found positive relationships between turnover and normative commitment. However, the relationship between continuance commitment and turnover was negative. In effect, employees who were staying with the organization because they wanted to or felt they ought to, indicated higher involvement and enjoyment with work activities. In contrast, employees who were staying with the organization because they felt they needed to indicated less involvement with the organization, and expressed dissatisfaction with work activities. Thus, their intention to leave the organization was higher.

There are many extrinsic variables that employees must consider in deciding whether to continue their employment with a company. Extrinsic items are those that have outcomes bestowed upon them by someone else (praise, rewards, bonuses, policies). For these types of rewards the employees need to look beyond themselves and assess their perceived value of what they have been given. (Moorman, 1993).

In explaining the significance of job satisfaction, Jennings (2008) refers to Leavitt's (1996) statement that there is a multitude of reasons an employee will remain within a given company. High pay, excellent benefts, job security, and a company retirement plan are among the most sought after components of the perfect job. Unfortunately, any one of these attributes alone is not enough to outweigh the problem of low perceived job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction is one of the most important attributes of the employment relationship. The most important element of job satisfaction is job security. (Khaleque & Chowdhury, 1983).

The results of job satisfaction are extremely influential to any organization, not only to its HR function, but also to its entire operation. It alone can be a determining factor affecting employee effciency, productivity (quality), and absenteeism, as well as turnover (Rahman, Rahman, & Khaleque, 1995).

Job satisfaction has shown positive effects on both sides of the manufacturing equation. That is, job satisfaction mitigates toward employees who are not only less likely to jump to a different company, but also more likely to be attentive to product quality. If employees are satisfed in their roles it is assumed that their output quantity is greater and that their quality is higher. The employer must also be satisfed with the employee. These are accomplished by frst recognizing that each side needs the other. If employers feel there are many people from which to choose to fill a particular need, they have an advantage. If, as well, workers perceive a high availability of alternative jobs, they have an advantage. Both of these conditions were found to be particularly true in the maquiladora plants, with their environment of high labor availability, high position availability, and high turnover. The employee can assume an advantage when he or she has a particular skill that is in demand. Job satisfaction is a two way street and involves participation. For this to happen, a relationship must evolve between the employer and the employee. Job satisfaction is therefore distinct from other organizational constructs. (Hinton & Biderman, 1995).

Pairing job satisfaction with length of employment, however, takes a look at yet another relationship. This relationship is determined by how the employees are viewed now not only by their current employer, but how they can be perceived by prospective employers. Employees who have been in the workforce for a number of years have qualities and experience that can make them valuable assets to a company. If recognized and rewarded consistently by the current employer, the employees usually take minimal action in looking for other employment offers. Thus, they exhibit affective and normative commitment, much to the advantage of the company. Experience is only one of a gamut of qualities that length of employment can pair with perceived job satisfaction. Others include the ability to work and relate with coworkers and customers, and the pattern of work and nonworking satisfaction. (Shaffer,1987). Initially, employees can be satisfed with high starting salaries. But after a few years' experience, most employees recognize the importance of job security. (Rahman, Rahman, & Khaleque, 1995).

Job satisfaction is a combination of cognitive and affective contentment for an individual within a company. Cognitive satisfaction is based on non–emotional based conditions that are evaluative of outcomes and opportunities. These include working conditions and the nature of the job. These questions are for appraisals of the job itself, not for descriptions of the feelings. Affective satisfaction is one that is based on the overall positive emotional view of the situation. (Moorman, 1993)

Many authors referred to the importance of a satisfed workforce, given that they are the primary asset to the firm. (Brierley and William, 2001; Belkaoui, 1989; Dole and Shroeder, 2001).

Turnover is a significant and costly problem for the maquiladora Industry (Garcia and Cox, 2007b). Higher levels of job satisfaction have been strongly linked to the desire to remain in a firm in the literature (Porter and Steers, 1973; Arnold and Fieldman, 1982).

As noted earlier, job satisfaction is a two–way street requiring participation from both the employer and the employee. This is particularly true when both sides perceive advantages that can be used. In the maquiladoras in the authors' studies, the employers are in an environment where job openings can be filled, albeit with additional costs. The employees, in turn, are in a job market where jobs are easily acquired. In order for turnover percentages to decrease, with the accompanying advantages of lower HR costs, lower absenteeism, and potentially higher quality and output, one side or the other must make a move. Individual workers are essentially powerless, and union activity within the maquiladoras is not strong. Thus, it is diffcult for the workers to agitate for better working conditions overall, leading to their own greater organizational commitment and attachment. In this case, it is the employing maquiladoras, themselves, who are in a position to improve conditions leading to a lower turnover rate.

Norris and Niebuhr (1983) pointed out that job satisfaction is a variable largely associated with the current work environment, which makes it a less stable variable than organizational commitment which is formed over a longer period of time. The immediate work environment is changing constantly in the maquiladora industry due to high turnover even at the supervisory level, and the actions of those supervisors play a key role in shaping that environment.

Work Motivation

Luthan (1998) defines motivation as, "a process that starts with a physiological defciency or need that activates a behavior or a drive that is aimed at a goal incentive". Therefore, the key to understanding the process of motivation lies in the meaning of, and relationship among, needs, drives, and incentives. Relative to this, Minner, Ebrahimi, and Watchel, (1995) state that in a system sense, motivation consists of these three interacting and interdependent elements, i.e., needs, drives, and incentives.

Research on work motivation has shown that workers' performance and satisfaction is affected by job motivation. For example, Brown and Shepherd (1997) give a comprehensive definition of the characteristics of the work in four major categories: knowledge base, technical skills, values, and beliefs. They report that workers will succeed in meeting this challenge only if they are motivated by deeply–held values and beliefs regarding the development of a shared vision. According to Vi–nokur, Jayarantne, and Chess (1994), employment conditions assess their impact on workers' job satisfaction. Some motivational issues were salary, fringe benefts, job security, physical surroundings, and safety. Certain environmental and motivational factors are predictors of job satisfaction. On the other hand, Colvin (1998) shows that financial incentives will get people to do more of what they are doing, Silverthrone (1996) investigates motivation and managerial styles in the private and public sector. The results indicate that there is a little difference between the motivational needs of public and private sector employees, managers, and non–managers.

Affective Commitment

According to Mowday, Steers, & Porter, (1979), Affective commitment has been defined as "identifcation and involvement with the organization via believing in the organization's values and goals, exerting effort on behalf of the organization, and desiring to remain with the organization".

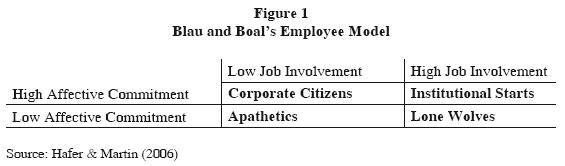

Meyer and Allen (1991a) and Allen and Meyer (1990) defined Affective commitment as an important part of Organizational Commitment, including also continuance commitment, and normative commitment. Affective commitment represents the type of commitment utilized in the Blau and Boal (1987) model as shown in figure 1.

Also, according to Meyer and Allen (1991b) Affective commitment refers to the employee's emotional attachment to the organization. Employees with strong affective commitment remain with the organization because they want to do so. According to these authors, the most desirable profile of organizational commitment amongst employees, especially those involved in the services industry which demands continuous good service, is affective commitment which is the most prevalent theme in the Meyer and Allen (1991) model.

Methodology

This study used a descriptive survey design. As referred by Ezeani (1998), the purpose of descriptive surveys is to collect detailed and factual information that describes an existing phenomenon.

The target population of the study was direct workers in a Maquila Industry in Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico.

An analysis was made in SPSS of data from 100 production workers. One hundred direct employees (25 men and 38 women, mean age = 26–35 years, with an average of not completed high school (eleventh grade) participated in a survey formatted with questions to determine their level of job satisfaction, work motivation, their degree and level of organizational commitment, and how their job security and relationships with co–workers affected their decision to continue their employment with the company. All participants were treated in accordance with the "Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Codes of Conduct" (American Psychological Association, 1992).

Description of the Sample

The sample for this study was drawn from a small Manufacturing facility in Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico.

The workforce encompasses approximately 120 employees across the production department. A total of 100 employees from the production area participated in this study. Study participants included only non–supervisory employees. From the 100 employees who participated in this survey, only 66 answered the questionnaire (66%).

Instrument

A modifed questionnaire tagged Work Motivation, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment was used for the collection of data on the study. The questionnaire was specifically designed to accomplish the objectives of the study. The frst section collected information such as age, gender and experience.. The second section contained the items, and was divided into three parts:

• Part 1. This part contains fifteen items that measure job motivation.

• Part 2. This part contains fifteen items that measure personnel's job satisfaction.

• Part 3. This part contains fifteen items that measure organizational commitment.

It is a 45 –item questionnaire using a 5 point Likert scale with responses ranging from Strongly Disagree= 1; Disgree = 2; undecided =3 ; Agree =4; and Strongly Agree =5. The items were adapted from The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionaire and we added some additional questions. The modifcation yielded an r = 0.84 Cronbach Alpha.

Procedure

The researcher administered the instrument to direct employees after the approval of their management. Following the instructions on the instrument, the questionnaires were filled and returned.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics, Pearson Multiple Correlation, and Multiple classifcation methods with t–test were employed to analyze the collected data.

Results

The results of the analysis on the study are presented as follows:

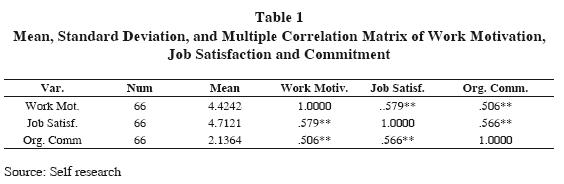

Research question. What is the relationship between work motivation, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment in direct employees of the maquiladora industry?

For the above question, the result in table 1 above reveals a positive correlation between work motivation and job satisfaction with coeffcient value of r =.579. work motivation also correlated with organizational commitment with a value of r = .506.

For job satisfaction and organizational commitment, we find a positive high correlation too of r= .566.

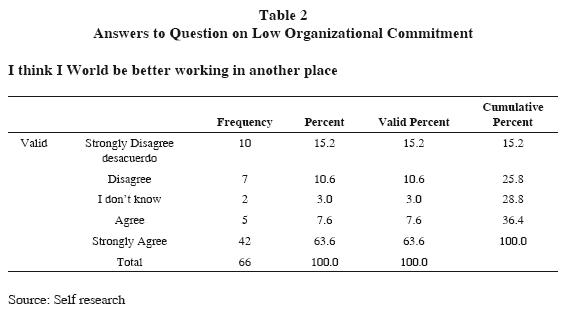

As we can see on Table 2, 42 of 66 (63.6%) answered positively to their low organizational commitment, since they accept to feel better if working somewhere else.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that a high correlation exists between perceived motivation, job satisfaction, and commitment,. No significant difference was observed in the perceived motivation of men and women direct employees.

The correlation that exists in this study among perceived work motivation, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment corresponds with (Brown and Shepherd, 1997) who reported that motivation improves workers' performance and job satisfaction. The result also agrees with Chess (1994), reported that certain motivational factors contribute to the prediction of job satisfaction. Tang and LiPing (1999) report that a relationship exists between job satisfaction and organizational commitment, and Woer (1998) finds that organizational commitment relates to job satisfaction, which both support this result. Furthermore, Stokes, Riger, and Sullivan's (1995) report that perceived motivation relates to job satisfaction, commitment, and even intention to stay with the firm corroborates this present result.

The second result obtained on this study was that no significant difference was observed in the perceived work motivation of men and women. Williams in Nwagu (1997) reported that motivation potential is linked to five core characteristics that affect three psychological states essential to internal work motivation and positive work outcome. That idea complements the present finding. Similarly, the finding by Colvin (1998) that financial incentives increase productivity, corroborates this result. Men and women have the same perceived work motivation if they are given the work environment and incentives that they need and deserve.

As noted previously, the initial study that provided the impetus for further investigation was conducted in a relatively small division of a larger corporation; i.e., the guitar string manufacturing arm of Fender, a large maker of musical instruments and supporting products.

This study also echoed most of the previous findings. That is, when companies deal with worker turnover in a labor market with many opportunities for their workers, they find (1) high salaries work for a while, but "the grass is always greener." (2) Praise works for a while, but eventually becomes wearing, if used to the exclusion of other items. (3) Good supervision works for a while, but not if that is the only good part of the job. The numbered list could go on for several more numbers, but each, used in isolation or with one or two others, will not increase worker commitment and decrease turnover. Companies must strive to provide the entire package, and if they are unsuccessful, but seen as striving to do better, it is likely the workers will take cognizance and increase their organizational commitment.

Much of the previous research in this area has involved a survey questionnaire; future research is needed using more in–depth methods of data collection such as interviews to examine the range of variables that impact on job satisfaction and turnover intentions and ways in which firms can increase job satisfaction and reduce turnover intentions. The variables examined in this study accounted for almost 32 per cent of the variation in job satisfaction and 65 per cent of the variation in intentions to remain in the firm. Qualitative research would be beneficial in identifying other influences on job satisfaction and intentions to remain in the firm. For example, the impact of training and supervisory actions such as workload allocations and in turn on job satisfaction and turnover intentions is potentially important. Also, variables such as stress and burnout may be important in explaining differences in levels of job satisfaction and turnover intentions between employment areas.

Future quantitative research should include a more comprehensive measure of intentions to remain in the firm, as the measure included in this study is based on very few items. Brierley (1999) pointed out that turnover intentions have been measured as intentions to leave the job, and intentions to go to a different economic sector; these different facets could be examined in future research. A distinction between short– and long–term turnover intentions would be particularly relevant. significant differences were found in a number of variables between the firms and an examination of the reasons for differences in those variables and a breakdown of the category into different size firms would be potentially fruitful for future research. Further investigation of the impact of other demographic variables such as those found to be significant in this study (work area, gender, education) and variables not examined in this study (for example, plant location) would add to the further development of the job satisfaction model. Lastly, a comparison of perceived supervisory actions in US and Australia revealed differences and a potentially fruitful area for future research would be a cross–cultural study of supervisory actions and job satisfaction.

In the outsourcing manufacturing environment where companies' value employee continuity and competition drives the need for high productivity, job satisfaction of direct employees will continue to be an area of considerable importance for the firms. Improving job satisfaction and increasing intentions to remain in the firm is not an easy task for the firms given the pressures of the modern business environment. However, managing these pressures is essential for direct employees, as a failure to do so is likely to have far reaching consequences.

This may well be a fertile feld for longer range research within the specific maquiladoras to determine, with employee input, which job improvements would give the most "bang for the buck" when compared or ranked with other improvements.

References

ALLEN, N. and J. MEYER (1990). "Organizational socialization tactics: A longitudinal analysis of links to newcomers' commitment and role orientation". Academy of Management Journal, 33(4) in Hafer and Martin (2006) Institute of Behavioral and Applied Management, 8,1, 2–3. [ Links ]

AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION (1992). "Ethical principles of psychologists and codes of conduct". American Psychologist, 47, 1597–1611. [ Links ]

ANGLE, H. and J. PERRY (1981). "An empirical assessment of organizational commitment and organizational effectiveness". Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 1–14. [ Links ]

ARNOLD, H. and D. FELDMAN (1982). "A Multivariate Analysis of the Determinants of Job Turnover". Journal of Applied Psychology, June, 350–360. [ Links ]

BLAU, G. and K. BOAL (1987). "Conceptualizing how job involvement and organizational commitment affect turnover and absenteeism". Academy of Management Review, 12(2), 288–300, in Hafer and Martin (2006) Institute of Behavioral and Applied Management, 8,1, 2–3. [ Links ]

BROWN, B. (2003) "Employees' Organizational Commitment and Their Perception of Supervisors' Relations–Oriented and Task–Oriented Leadership Behaviors", Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Falls Church, Virginia. [ Links ]

BROWN, J. and B. SHEPPARD (1997). "Teacher librarians in learning organizations". Paper Presented at the Annual Conference of the International Association of School Librarianship, Canada. August 25–30. [ Links ]

BYCIO, P., R. HACKETT and J. ALLEN (1995). "Further assessment's of Bass's (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership". Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 468–478. [ Links ]

CARRILLO, J. y J. SANTIBÁÑEZ (1993). Rotación de personal en las maquiladoras de exportación en Tijuana. México: Secretaria de Trabajo y Previsión Social / Colegio de la Frontera Norte. [ Links ]

COHEN, A. (1996). "On the discriminant validity of the Meyer and Allen measure of organizational commitment: How does it ft with the work commitment construct?" Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56, 494–503. [ Links ]

––––––––––and C. Kirchmeyer (1995). "A multidimensional approach to the relations between organizational commitment and nonwork participation". Journal of Vocational Behavior, 46, 189–202. [ Links ]

COLVIN, G. (1998). "What money makes you do". Fortune 138 (4), 213–214. [ Links ]

DECOTIIS, T. and T. SUMMERS (1987). "A path analysis of a model of the antecedents and consequences of organizational commitment". Human Relations, 40, 445–470. [ Links ]

DUNHAM, R. , J. GRUBE and M. CASTAÑEDA, (1994). "Organizational commitment: The utility of an integrative definition". Univ. Wisconsin, graduate school of business, Madison WI 53706–1323. [ Links ]

GARCIA, B. and J. COX (2007a). "5S KAIZEN – A Tool to Improve Productivity, Effciency and Uniformity of Products in Manufacturing and Industrial Sectors" presented at the 37th International Conference on Computers and Industrial Engineering, Alexandria, Egypt. [ Links ]

––––––––––(2007b). "Management and Development of a Work Force: The Challenge of Sustainability", Paper presented at IAMOT2008, Dubai, EAU. [ Links ]

GARCIA, B. and L. RIVAS (2007). "A turnover perception model of the general working population in the Mexican cross–border assembly (maquiladora) industry". Innovar, Vol.17, No.29, Bogotá, Jan./June 2007 [ Links ]

HINTON, M. and M. BIDERMAN (1995). "Empirically derived job characteristics measures and the motivating potential score". Journal of Business Psychology, 9, 355–364. [ Links ]

IRVING, P., D. COLEMAN and C. COOPER (1997). Further assessments of a three–component model of occupational commitment: Generalizability and differences across occupations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(3), 444–452. [ Links ]

ITO, J. and C. BROTHERIDGE (2005) "Does supporting employees' career adaptability lead to commitment, turnover, or both?" Human Resource Management, Vol. 44, No. 1, 5–19. [ Links ]

JENNINGS, D. (2008). "Is Length of Employment Related to Job Satisfaction?" Department of Psichology, Missouri Western State University, 1–2. [ Links ]

JERMIER, J. and L. BERKES (1979). "Leader behavior in a police command bureaucracy: A closer look at the quasi–military model". Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 1–23. [ Links ]

KHALEQUE, A. and N. CHOWDHURY, (1983, May). "Perceived importance of job facet and over all job satisfaction of top and bottom level industrial managers". Paper presented at the proceedings of the third Asian Regional Conference of the International Association for Cross–Cultural Psychology, Bang, Malaysia. [ Links ]

LEAVITT, W. (1996). "High pay and low morale–Can high pay, excellent benefts, job security, and low job satisfaction coexist in a public agency?" Public Personnel Management, 25, 333–341. [ Links ]

LOUI, K. (1995). "Understanding employee commitment in the public organization: A study of the juvenile detention center". International Journal of Public Administration. 18(8), 1269–1295. [ Links ]

LUTHANS, F. (1998). Organisational Behaviour. 8th ed. Boston: Irwin McGraw–Hill. [ Links ]

MAERTZ, C. Jr., R. GRIFFITH, N. CAMPBELL AND D. ALLEN (2007) "The effect of perceived organizational support and perceived supervisor support on employee turnover," Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 28, 1059 – 1075. [ Links ]

MEYER, J. and N. ALLEN (1991a). "A three–component conceptualization of organizational commitment". Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89. [ Links ]

––––––––––(1997). Commitment in the workplace. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [ Links ]

––––––––––(1991b). "A three component conceptualization of organizational commitment". Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61–89 in Hafer and Martin (2006) Institute of Behavioral and Applied Management, 8,1, 2–3. [ Links ]

MEYER, J., T. BECKER and R. VAN DICK (2006) "Social Identities and Commitments at work: toward an integrative model". Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 27, 665–683. [ Links ]

MEYER, J., S. PAUNOMEN, I. GELLATLY, R.GOFFIN and D. JACKSON (1989). "Organizational commitment and job performance: It's nature of the commitment that counts". Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 152– 156. [ Links ]

MINER, J., B.EBRAHIMI and J WACHTELl (1995). "How defciency in management contributes to the United States' competiveness problem and what can be done about it?" Human Resource Management. Fall, 363. [ Links ]

MOORMAN, R. (1993). "The influence of cognitive and affective based job satisfaction measures on the relationship satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior". Human Relations, 46, 759–775. [ Links ]

MOWDAY, R.., L. PORTER and R. STEERS (1982). Organizational linkages: The psychology of commitment , absentees , and turnover. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [ Links ]

–––––––––– R. STEERS and L. PORTER (1979). "The measurement of organizational commitment.". Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14, 227–247. [ Links ]

NORRIS, D.and R. NIEBHUR (1983). "Professionalism, Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction in an Accounting Organization". Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 9, No. 1, 49–59. [ Links ]

NWAGWU, C. (1997). "The environment of crisis in the Nigerian education system". Journal of Comparative Education 33 (1), 87–95. [ Links ]

O'QUIN, K. and S. LOTEMPIO (1998). "Job satisfaction and intentions to turnover in human services agencies perceived as stable or nonstable". Perceptual Motor Skills, 86, 339–344. [ Links ]

PELLED, L and K. XIN (1997) "Birds of a feather: leader–member demographic similarity and organizational attachment in Mexico". Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 8, No. 4, 433–450. [ Links ]

PORTER, L. and R. STEERS (1973). "Organization, Work and Personal Factors in Employee Turnover and Absenteeism". Psychological Bulletin, August, 151–176. [ Links ]

RAHMAN, T., T. RAHMAN and A. KHALEQUE (1995). J"ob facets and job satisfaction of bank employees in Bangladesh". Psychological Studies, 40, 154–156. [ Links ]

RILEY, D. (2006). "Turnover Intentions: the mediation effects of job satisfaction, affective commitment and continuance commitment". The University of Waikato. [ Links ]

SHAFFER, G. (1987). "Patterns of work and nonwork satisfaction". Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 115–123. [ Links ]

SILVERTHRONE, C. (1996). "Motivation and management styles in the public and private sectors in Taiwan and a comparison with United States". Journal of Applied Social Psychology 26 (20), 1827–1837. [ Links ]

SPECTOR, P. (2000). Industrial and organizational psychology: Research and practice (2 Ed.). USA. John Wiley and Sons. [ Links ]

STEERS, R. (1975). "Problems in the measurement of organizational effectiveness". Administrative Science Quarterly, 20, 546–558. [ Links ]

SWEENEY, B. and B. BOYLE (2005) "Supervisory actions, Job Satisfaction and turnover intentions of Irish Trainee Accountants" The Irish Accounting Review. Dublin: Winter 2005. Vol. 12, Iss. 2; 47, 27. [ Links ]

TANG, T. and J. LIPING (1999). "The meaning of money among mental health workers. The endorsement ethic as related to organizational citizenship behaviour, job satisfaction and commitment". Public Personnel Management 28, 15–26. [ Links ]

VINOKUR, K., S. JAYAARATNE and W. CHESS (1994). "Job satisfaction and retention of social workers in public agencies, non–proft agencies and private practice: The impact of work place conditions and motivators". Administration in Social Work 18 (3) 93–121 [ Links ]

WIENER, Y. and Y.VARDI (1980). "Relationships between job, organization, and career commitments and work outcomes: An integrative approach". Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 26, 81–96. [ Links ]